Abstract

Culture is a specific form of human activity that enriches the lives of citizens. It also participates in economic growth, employment and social cohesion, assists in the transformation of urban and rural areas and promotes sustainable tourism. In the late 20th century, the theoretical reflection was presented as a factor that differentiates (separates) and not as a phenomenon of cohesion. At present, the attention of experts is more devoted to group culture. The paper deals with the importance and possibilities of support of cultural services. The aim of the study is, based on the theoretical knowledge, to point to the current state of provision of public and commercial services to the citizen and their proportionality in a democratic society. The study provides a literary research in the field and an analysis of cultural infrastructure on samples of selected self-governing regions. This study compares the financing of the culture of the Bratislava and Žilina self-governing regions using the deduction method and benchmarking. The analytical part of the paper will use the method of deduction and comparison as its aim is to decompose the possibilities of public and private forms of cultural support compared to the cultural infrastructure on the sample of two Slovak self-governing regions.

Keywords: Cultureself-governing regionbenchmarkingcultural situation

Introduction

The current situation in the area of culture in Slovakia is not very satisfactory. The society does not attach it enough importance and often overlooks its significant impact on other areas of life. It is perceived as a superstructure activity without which it is possible to exist, which does not need to be cared much and which does not have great economic potential because it is dependent on public support. The reason may be the fact that the area of culture has not undergone any dynamic or systematic transformation process up to yet. At European level there is a consensus that perceives culture as a public service directly related to the quality of life and as a matter of identity of the place and of the citizens. The current and urgent problem is local (regional, local) culture. The society, respectively, the citizens do not lose interest in culture, but on the contrary. Improving the availability of information is linked to a more vigorous fulfillment of their right to participate in their free time in cultural life. From the economic point of view, it is not possible to talk about the cultural sector as a marginal sector, as its share of GDP is comparable to shares of some industrial sectors. It also makes it possible to create employment, high added value and, as it is not demanding for raw materials and energy, does not pose a burden on the environment (Szkutnik & Szkutnik, 2018).

The Ministry of Culture of the SR (MC SR) is the central authority of the state administration, which covers the area of culture and art in Slovakia. Within the scope of its competence, it provides protection of the monument fund, cultural heritage, state language, librarianship, art and audiovisual media. The Ministry of Culture is also responsible for the development of cultural and educational activities and for the presentation of Slovak culture and art in foreign countries. The entire network of cultural objects in Slovakia was built after 1948. At present, it is possible to visit approximately 4,800 cultural objects (libraries, museums, galleries, educational establishments, etc.), but their use is not exclusively of a cultural character. Especially in municipalities with fewer inhabitants, the buildings are also used for the provision of commercial services. As an example it is possible to mention renting of cultural homes, respectively, their parts for various social events (weddings, cakes, etc.).

Benchmarking can take place at both strategic and operational levels. Strategic benchmarking focuses on strategic studies on the preparation and implementation of permanent and effective improvement programs, change management, and leadership styles. All these aspects influence the formation of vision, develop strategies and competencies of leaders and respect the requirements of citizens. The essence of operational benchmarking is to achieve organizational goals through processes whose improvement is conditional on the best experience (Merickova, Nemec, Sicakova Beblava, & Beblavy, 2010).

Literature Review

The social and cultural life of McQuil (1999) has been strongly determined by family, community, personal relationships, and religion in a traditional society. The psychological aspect in Freud's theory (1990) says that man creates a culture because his life is different from animal life. Williams (1983) distributes culture as a subject of independent exploration, that is, culture represents everything that has been created by man. Based on this claim, he created the notion that there are no boundaries of knowledge when examining a culture, because it is essential for a person to understand his product. Hofstede and Bond (1988) consider culture as a shared system of values, beliefs, attitudes and behaviors that distinguish members of one social group from another. The wider meaning of culture is also mentioned by the Czech philosopher Sokol (2002). Through the attributes of culture, which, according to the author, are language, education, religion, art, science, experience and techniques, people can understand themselves and the environment in which they live. Sokol further states that a man can live out of what his closest taught him first, who have elucidated the meanings of the world and enabled him to become responsible above all for himself. Nanda and Warms (2007) critically point out that culture is made up of dynamically changing elements and therefore its internal cohesion cannot be a flawless mechanism. Slusna (2013) considers the basis of the culture of human activity, whose common ground is the improvement of the achieved or given state.

Methodology

Slovakia is a country with cultural potential. The cultural landscape has been influenced by the geographical location in the center of Europe in the past. Slovak culture is an indispensable part of the Central European Cultural Circle, whose rich foundations have built and developed many ethnicities and nations. The historical cultural image also formed a large number of dramatic events, political or social contradictions. Despite all these facts, on the territory of Slovakia there has been continually formed and developed the original ethno-cultural territorial units, which participated in the rich articulation of the cultural image of the landscape.

Culture in the broader sense can be described as a synonym of civilization. It allows the development of thinking, taste, morale or strengthening civil society. Its meaning is indisputable, and society cannot simply exist without culture. On the one hand, emphasizing the importance of culture is a positive signal, on the other hand, there is an increase in expectations towards those who move in the cultural sphere as initiators, organizers and actors of cultural life.

Benchmarking is a method of improving through learning from others (Ahmed & Rafiq, 1998). It is a continuous activity that seeks to find effective practical procedures within an organization with similar functions and whose purpose is to achieve better results in one's own organization. However, it can also be understood as a cost comparison process. The intent of the information obtained through benchmarking is to use them to achieve a change that is reflected in the increased quality of the services provided. Thus, it is easy to say that benchmarking is the pursuit of others in order to learn from them, and it is not a question of bullying or espionage (Basak & Shapiro, & Tepla, 2005).

Under the conditions of the Slovak Republic, cultural products (and also services) are created, in particular, by the institutional basis of culture that can be perceived from multiple angles. Cultural sector institutions are cultural institutions and other cultural institutions operating in other departments (for example, the Museum of St. Anthony and the Museum of Coins and Medals in Kremnica, which belong to the agriculture sector). In terms of defining the individual levels of culture, they are state, self-governing (general, urban and regional) and third and private institutions, respectively. of the business sector (Filo, Strelkova, & Chomova, 2010; Meila, 2018).

Culture products are an indispensable foundation for the healthy functioning of society and it is therefore essential that these products are financially supported (whether through public and private sources or other funding options). Cultural provision is most often associated with the financing or co-financing of culture from public sources, from public administration budgets (Chlebikova, Misankova, & Kramarova, 2015; Gregova, 2014). From the point of view of Slovak legislation, the conditions for the process of financing the culture are regulated by three legal regulations, which are Act no. 231/1999 Coll. on state aid, Act no. 523/2004 Coll. on Financial Rules and Act No. 434/2010 Coll. on the provision of subsidies within the competence of the Ministry of Culture of the Slovak Republic (Kliestik, Musa, & Frajtova-Michalikova, 2015).

Since 1996, Slovakia has been divided into 8 self-governing regions, which are concentrated around the largest cities. Individual regions differ in several aspects, such as: population, density of population, age structure, natural specifics or cultural infrastructure (Neary, Horak, Kovacova, & Valaskova, 2018). The capacity of self-governing region in the field of culture is defined in the Act of the National Council of the Slovak Republic no. 302/2001 Coll. on self-governing regions, according to which: "the self-governing region creates conditions for the creation, development and presentation of cultural values and cultural activities and cares for the protection of the monument fund". The area of culture can also be promoted by foreign public institutions or foundations. However, due to their large number, it will be enough to give an example such as the International Vysegrad Fund or the Foundation Anna LINDH.

The International Visegrad Fund is an international organization based in Bratislava, officially established in 2000 by the Visegrad Group governments (V4 - Slovakia, Czech Republic, Hungary and Poland). The main mission of the Fund is to promote cooperation between V4 countries through involvement in joint cultural, scientific and educational projects, provision of youth exchanges and promotion of tourism (Valaskova, Kliestikova, & Krizanova, 2018). The Anna Lindh Foundation for Dialogue between Cultures, Anna LINDH, has been operating since 2005. It works on the principle of the National Networks platforms formed by each country within the framework of the Euro-Mediterranean Partnership. The Foundation has its own grant system, which funds cultural projects and projects in the field of sustainable development, nurture or education. The analysis in this study focuses on the comparison of the cultural infrastructure of two self-governing regions - the Bratislava Region (BR) and the Žilina Region (ŽR). The main reason for selecting BR is the fact that Bratislava, as the capital, represents the cradle of cultural events in Slovakia. Culture has a deeply rooted tradition in this city. The largest number of cultural events is held regularly and the number of cultural institutions is even comparable to most developed European cities. The top professional art institutions in the region include the Slovak National Theater and the Slovak Philharmonic. Significant cultural events also take place in other self-governing regions. In order to make it easier to compare the cultural infrastructure of BR with another self-governing region, as a representative sample of other region, Žilina Region was chosen.

From a general point of view, cultural institutions and facilities can be included under the cultural sphere: galleries, museums, theatres, cinemas, libraries, astronomical facilities and workplaces; broadcasting: radio and television program services; printed periodical press; published non-periodical publications; church and religious societies (Michalski et al., 2018). All these aspects are subject to the annual state statistical survey in the field of culture carried out by the Statistical Office of the Slovak Republic in cooperation with the Ministry of Culture for a period of three years and issued by a decree. However, the following analysis of the cultural infrastructure of BSK and ŽSK is more specifically focused on theaters, museums, galleries, public libraries and events in cultural and educational establishments.

Results

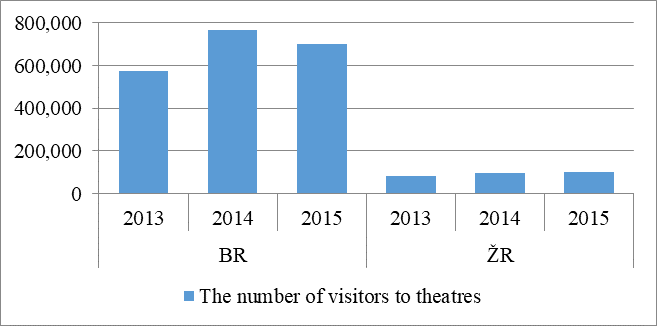

In the years 2013-2015, both self-governing regions recorded an increase in the number of theaters as well as the number of visitors (see Figure

In the years 2013-2015, both self-governing regions recorded an increase in the number of theaters as well as the number of visitors (see Figure

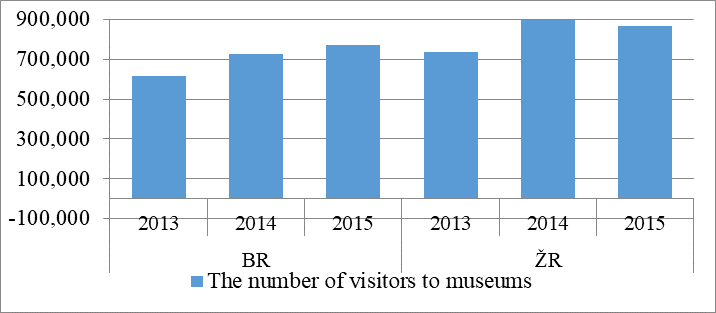

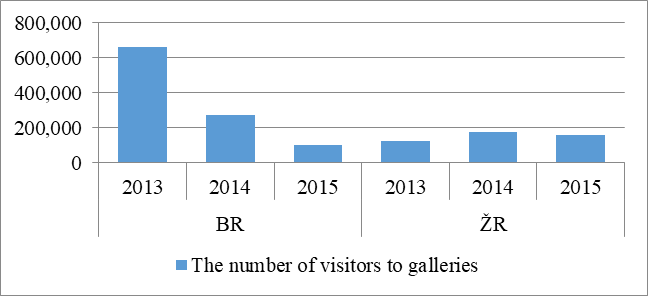

The situation about the museums is very different from number of visits of theatres as we can see that in Žilina region there is higher number of visits every single year out of all three that were chosen for the research. The number of galleries did not change even in one self-governing region in 2013 and 2014. As in the case of museums, the number of galleries from 2015 includes both branch offices and exposures. Significant change can be seen in the number of visitors to the BR. The number of visitors to the galleries has dropped sharply (compared to the years 2013 and 2015, the decline in traffic was almost 85%). ŽR had a higher number of galleries and no significant changes were recorded in the number of visitors. The number of visitors to galleries in the BR and in the ŽR in 2013 – 2015 is visualised in the following Figure

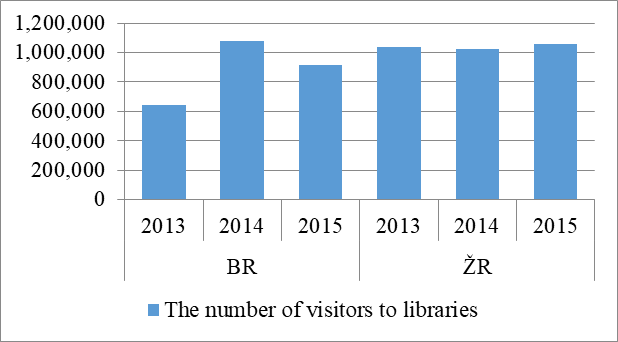

2013 was very strong year for Bratislava region, but the other years we can see a huge decrease. First two years out of the time series were of stronger number of visits in Bratislava region than in Žilina region, but in the last year, there was a higher number of visitors of galleries in Žilina region than in Bratislava region. In the years 2013 and 2014, an increase in the number of public libraries occurred and, in the years 2014 and 2015, the number of libraries in both self-governing regions is reduced. The consequences the came from that fact can be seen in the Figure

The ŽR had a much larger number of public libraries than the BR. Based on Figure

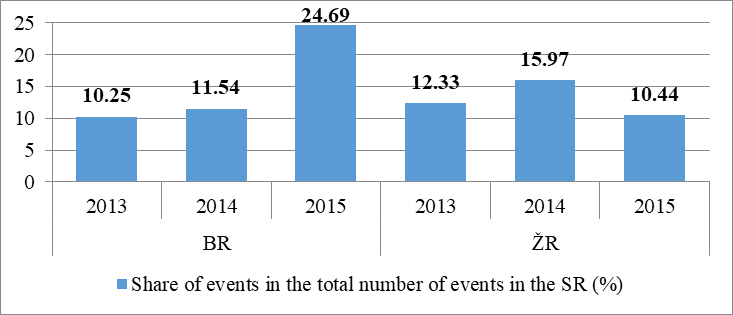

The last part of the analysis of cultural infrastructure concerns events in cultural and educational institutions. Share of the number of events in BR and ŽR in the total number of events in SR is visualised in the following Figure

In 2013, 62 748 events took place throughout the country. Subsequently, in 2014, the number was significantly reduced to 21 376 events, and in 2015 the number increased to 47 621 events. The highest number of events was organized in the BR in 2015, with a total of 11 757 events, which represented almost 25% of the total events organized in the cultural and educational institutions throughout the SR.

Conclusion

The previous section compared the cultural situation in selected self-governing regions - in Žilina Region (ŽR) and in the Bratislava Region (BR). The reason for choosing BR was its specific status as its capital city and the largest city of the SR - Bratislava, in which the largest part of the culture is concentrated, is situated on its territory, as there is an overlapping of state, metropolitan, regional and local (urban and rural) culture. At the same time, this region is characterized by the cultural excellence of its inhabitants and by generating numerous independent and alternative cultural and artistic settings. The following suggestions and recommendations in this part of the study are focused on the area of culture in ŽR, which was chosen as a representative sample among the other seven Slovak regions, which are characterized by somewhat less cultural potential compared to BR. The basic prerequisite for the development of culture is its efficient and meaningful financing. Since January 2017, the ŽSK has launched a new grant system under General Binding Regulation no. 46/2016. For the year 2017, a call was also made for the culture area, where the volume of funding (EUR 124,364) was set, a minimum (EUR 300) and a maximum grant (EUR 1,500) per application. Recommendations for ŽR can be directed to the future increase in the total volume of funds as well as to the increase of both limits, both the minimum and the maximum amount of the subsidy per application. At present, the applicant can only submit one application for one of the sub-programs within the call. It is therefore possible to propose that in the next years the applicant could submit a larger number of applications in one call. For example, a grant system of the BR compares to this principle, which allows the applicant to submit a maximum of 5 applications. Financial provision of culture at national, regional and local level is mainly linked to the budgets of public administration institutions. By 2015, the share of public spending on culture in GDP was around 0.4%, which, however, represents the smallest value compared to that of the surrounding European countries. The declining trend is also shown by the share of private household spending on culture, cultural services declined by almost 1 percentage point between 2011 and 2015. The cause can be found in the persistent inadequate position of culture in society. Cultural institutions and organizations are involved in the promotion of culture and can be divided into two groups depending on whether it is a form of public or private support for cultural services. In particular, the Ministry of Culture of the Slovak Republic (or organizations in its area of competence) and cultural funds active in the field of audiovisual, art, literature and music are involved in the public support of Slovak culture through grants and subsidies. The foreign sources provided by the International Visegrad Fund, the Anna Lindh Foundation and many others play an important role in promoting culture. Private support for cultural services can be understood as the provision of financial contributions, grants or donations from private foundations, companies and individual donors. In particular, foundations of private mobile operators and commercial banks are currently operating in Slovakia.

Both self-governing regions are unique in their culture. The BR can be said to be a cultural "leader", but the ŽR is not significantly lagging behind. It is possible to assume that the attractiveness of the Žilina region will increase in the following years. Results of the regions' visits state that ŽR was just after BR the second most visited Slovak region. This fact should be taken into account by the council itself in deciding on other possibilities to support the development of culture in the region.

Acknowledgement

This is paper is an outcome of project VEGA: 1/0544/19 Formation of the methodological platform to measure and assess the effectiveness and financial status of non-profit organizations in the Slovak Republic

References

- Ahmed, P. K., & Rafiq, M. (1998). Integrated benchmarking: a holistic examination of select techniques for benchmarking analysis. Benchmarking for Quality Management & Technology, 5(3), 225–242.

- Basak, S., Shapiro, A., & Tepla, L. (2006). Risk Management with Benchmarking. Management Science, 52(4), 542–557.

- Chlebikova, D., Misankova, M., & Kramarova, K. (2015). Planning of Personal Development and Succession. Procedia Economics and Finance, 26, 249–253.

- Filo, P., Strelkova, J. & Chomova, S. (2010). Kultouroperator. Professional book publication for cultural and tourism workers. Piestany: National Educational Center.

- Freud, S. (1990). About man and culture. Praque: Odeon.

- Gregova, E. (2014). Program Structure of Municipal Budgets in Slovakia. Proceedings of the 19th International Conference: Theoretical and Practical Aspects of Public Finance 2014. 53-63. Prague, Czech Republic.

- Hofstede, G., & Bond, M. H. (1988). The Confucius connection: From cultural roots to economic growth. Organizational Dynamics, 16(4), 5–21.

- Kliestik, T., Musa, H., & Frajtova-Michalikova, K. (2015). Parametric Methods for Estimating the Level of Risk in Finance. Procedia Economics and Finance, 24, 322–330.

- Mcquil, D. (1999). Introduction to mass communication theory. Praque: Portal.

- Meila, A. D. (2018). Regulating the Sharing Economy at the Local Level: How the Technology of Online Labor Platforms Can Shape the Dynamics of Urban Environments. Geopolitics, History, and International Relations, 10 (1), 181–187.

- Merickova, B., Nemec, J., Sicakova Beblava, E., & Beblavy, M. (2010). Contracts in the public sector. Bratislava: Transparency International Slovensko.

- Michalski, G., Blendinger, G., Rozsa, Z., Cierniak-Emerych, A., Svidronova, M., Buleca, J., & Bulsara, H. (2018). Can We Determine Debt To Equity Levels In Non-Profit Organisations? Answer Based On Polish Case. Inzinerine Ekonomika-Engineering Economics, 29 (5), 526–535.

- Nanda, S., & Warms, R. L. (2007). Cultural Anthropology. 9th Edition. Thomson: Wadsworth.

- Neary, B., Horak, J., Kovacova, M., & Valaskova, K. (2018). The Future of Work: Disruptive Business Practices, Technology-Driven Economic Growth, and Computer-Induced Job Displacement. Journal of Self-Governance and Management Economics, 6(4), 19–24.

- Slusna, Z. (2013). Aspects and Trends of Contemporary Culture. Bratislava: National Educational Center.

- Sokol, J. (2002). Philosophical anthropology. Man as a person. 2nd edition, Praha: Portal.

- Szkutnik W., & Szkutnik, W. (2018). Socio-economic convergence in models of endogeneous economic growth. Ekonomicko-manazerske spektrum, 12 (2), 1-14.

- Valaskova, K., Kliestikova, J., & Krizanova, A. (2018). Consumer Perception of Private Label Products: An Empirical Research. Journal of Competitiveness, 10 (3), 149-163.

- Williams, R. (1983). Culture and Society 1780-1950. 2nd edition, Columbia University Press.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

30 October 2019

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-070-9

Publisher

Future Academy

Volume

71

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-460

Subjects

Business, innovation, Strategic management, Leadership, Technology, Sustainability

Cite this article as:

Karpac*, D., & Bartosova, V. (2019). Benchmarking of Cultural Infrastructure of Selected Self-Governing Regions of the Slovak Republic. In M. Özşahin (Ed.), Strategic Management in an International Environment: The New Challenges for International Business and Logistics in the Age of Industry 4.0, vol 71. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 279-287). Future Academy. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2019.10.02.25