Abstract

As a key ambient factor in retail environment, music can refresh and create pleasurable memories and experiences for the shoppers. However, bringing up standardized findings in each study is not applicable. It is important to identify which musical characteristics positively affect the customers, allowing them to spend more time and money for shopping in retail stores. The content of those factors and the findings of past studies are emphasized due to national and international literatures. The purpose of this research is to identify the effects of background music dimensions (tempo and loudness) on customer attitude towards small-scale sporting goods retail stores. In accordance with this aim, subsequent to an in depth literature review, a conceptual framework was comprised and tested by means of statistical analysis of primary data collected by a questionnaire from 247 customers, shopping from a sporting goods store at Istanbul city center. Two conditions related tempo (fast / slow) and loudness (loud / soft) were organized as independent variables. A questionnaire respecting attitude towards store was applied to be responded by customers exposed to background music in the store. Experimental groups of 'fast tempo and high loudness' and 'slow tempo and low loudness' do not have a statistically significant effect on attitude towards the store. Hereby, correlation analysis is the major statistical method in the research. The findings define that the effects of tempo and loudness on customer attitude towards small-scale sporting goods store on a busy street are differentiated according to tempo and loudness groups.

Keywords: Background musicattitudetempoloudnessretail

Introduction

Retailers can prefer to take advantage of music to enhance their atmosphere and influence

customer behaviour in the shopping environment. Many store atmosphere variables (such as odour and

colour) that interact with music can dominate consumer perception, attitude, waiting time in the store or

repatronage intentions (De Nisco & Warnaby, 2013). Senses such as vision, hearing and olfaction

stimulate people to understand the world. They also affect a particular consumer behaviour in a positive

or negative way. Thus, sensory appeals that determine human behaviours or attitudes can be addressed

consistently in the different market segments of the retail environment. Target market segments

interacting with consumer senses provide competitive advantage (Farias, Aguiar, & Melo, 2013). There is

a significant effort in the retail sector to identify and use store background music. As a consequence, the

appropriate atmosphere conditions are accommodated to satisfy target customers. At this point, store

service setting can be decisive in the relationship between in-store music and customers' responses

(Roschk, Loureiro, & Breitsohl, 2016).

The physical properties determine the design dimension of the store. Architecture, layout and

display are important factors in terms of the store attractiveness. The social dimension of the store is

related to customers and store personnel. Ambient dimension includes atmospheric variables and defines

background stimuli (Kotler, 1973). Prominent variables are music, lighting and service layout (Blazquez,

2014). The determinants of the store atmosphere can influence customers' behaviours. This discovery led

to drastic changes in sensory marketing techniques. Today, manufacturers and retailers try to develop new

methods to affect the sensory experience of the consumer (Spence, Puccinelli, Grewal, & Roggeveen,

2014).

Literature Review and Theoretical Framework

Background Music

Music and other atmospheric variables have attracted attention in the retail / service literature

since Kotler (1973). Music can drive consumers' interest in the store (Borges, Herter, & Chebat, 2015).

An atmospheric variable is an element that affects individuals' perceptions and ultimately their total

experience in a given time and environment (Milliman & Fugate, 1993). Retailers use atmospheric

variables to address consumer sentiment and strengthen brand image. Music is an important factor to

build an impressive in-store experience for consumers and directly linked to the individuals' feelings

(Morrison & Beverland, 2003). Music is an alternative to enrich shopping experience (Roschk et al.,

2016). Kotler (1973) revealed the presence of atmospheric variables that affect shopping behaviour in the

Journal of Retailing. Among other atmospheric variables, the apparent importance given to music is due

to its dynamic nature. According to Schmitt (1999), music is highly influential on customers' sensory

experiences. Background music is one of the primary elements in the retail environment (Alpert & Alpert,

1990). Organizations can use background music to match positioning, brand image, store design, and

overall satisfaction from the store. Various types of background music can be used to differentiate service

areas (Morrison & Beverland, 2003). Younger respondents enjoy pop music at a medium tempo and

middle-aged respondents prefer pop and Turkish classical music at a slow tempo (Yildirim, Cagatay, &

Hidayetoglu, 2015). Furthermore, volume expectations are differentiated according to age groups and

gender. Designers and store owners can use atmosphere variables to extend the waiting time of consumer

and increase sales.

Music is an important variable to create an attractive store experience (Burghelea, Plaias, & El-

Murad, 2015). The background music evaluated very positively by customers strengthens positive

perception towards the environment (Yamasaki, Yamada, & Laukka, 2015). Positive in-store experience

can lead to increased sales. Moreover, background music can reduce the negative psychological state of

customers and provide a pleasant shopping experience (Herrington & Capella, 1996). Customers are more

impressed by the repetition of familiar music (Petruzzellis, Chebat, & Palumbo, 2014). The food industry

can try to achieve market goals by complementing food stimulants or cuisine with appropriate musical

variables (Fiegel, Meullenet, Harrington, Humble, & Seo, 2014). For instance, companies that market

chocolate products can use jazz-like music to increase interest in their products. However, music research

in the literature has disregarded the impacts of other noises within the store environment generally, but

different noises influence customers' perceptions and behaviours (Hynes & Manson, 2016).

Musical Tempo and Loudness Effects on Attitude

Retailers believe that store atmosphere variables affect customer behaviours, attitudes and

shopping results. Among the different atmospheric elements, the dimensions of music play a significant

role in influencing customer responses. Tempo and volume are important factors that target a specific

customer base in the retail environment. A musical work has a physical dimension (volume, tempo or

rhythm), an emotional dimension, and a preferential dimension according to customers' expectations

(Bruner, 1990). Cognitive perceptions are influenced by environmental factors such as music. Emotions

determine consumers' approaches to product or service quality. Conceptual sequences shaped by music

and other atmospheric variables determine cognitive process. The formation and spread of cognitive

perception show that music congruity has a weaker effect for unfamiliar products compared to those for

familiar products (North, Sheridan, & Areni, 2016). The reflection of music as an environmental element

takes place through emotional reactions. The emotional attitude of an individual will be decisive in the

formation of reality. Thus, an individual's emotional approach to situations will affect behavioural

process. The emotional context shaped by music would be conducive to the acquisition of knowledge

generated by this experience (Xu & Sundar, 2014). Energetic music stimulates emotions and soft music

brings tranquility. Fast tempo is more arousing than slow tempo (Spence et al., 2014; Zhu & Meyers-

Levy, 2005). The tempo of instrumental background music can increase customer density within the

store. Thus, slow tempo music can lead to increase sales by 38% compared to fast tempo music

(Milliman, 1982). The fast tempo of music allows customers to spend more enjoyable time in the store.

This finding shows that fast tempo is more effective than slow tempo (Soh, Jayaraman, Choo, &

Kiumarsi, 2015). Oakes (2000) classified the background music variables in the store environment as

musical dimensions (tempo, volume and genre) and their effects on consumer behaviour. Particular

musical tempo affects emotions diversely. For instance, low tempo music provides positive support to the

environmental psychology model (Mehrabian & Russell, 1974; Donovan & Rossiter, 1982) and

servicescapes theory (Bitner, 1992).

Musical tempo is a dimension to monitor the number of beats per minute (BPM) by using digital

sound technology. Standard levels for tempo and volume have not been established in previous studies,

they are varied in terms of research environment. Therefore, forthcoming analyses are supported to define

an optimal level of musical tempo and volume (Michel, Baumann, & Gayer, 2017). In the study, slow

tempo versions were within a band of 90-130 BPM, whilst fast tempo versions were within a band of

131-180 BPM. Different tempo versions of original music pieces were applied to manipulate tempo by

using digital technology. Volume is a basic dimension of music. It can be easily controlled by managers

in retail environment. The number of studies investigating the volume effect on consumer emotions is not

sufficient. However, volume is negatively correlated with shopping time (Milliman, 1982; Yalch &

Spangenberg, 1990). Customers can prefer to spend less time in the store if the background music is too

loud (Milliman, 1982). Volume can be adjusted to a standard level using headphones in laboratory

research (Oakes & North, 2006). In a retail environment, customers can be at different distances to the

audio source. Thus, measuring the effect of volume on customer sensations requires great attention.

Ramlee and Said (2014) show that high volume of music attracts people to visit a store, but creates

disturbing feelings in restaurants. Background music as an element of ambient atmosphere is an important

and easily manageable parameter in restaurants (Harrington, Ottenbacher, & Treuter, 2015). According to

Herrington and Capella (1996), tempo and volume of background music do not significantly affect

shopping time or customer spending. In the study, low loudness versions were preferable within a band of

60 - 65 dB, whilst high loudness limits were 66 -75 dB. Sound levels were checked by using a digital

decibel meter and were manipulated by pre-setting volume controls on amplifiers which powered the

loudspeakers in retail settings. The purpose of this study is to reveal the relationship between

experimental groups (Fast Tempo, Low Loudness; Slow Tempo, High Loudness; Fast Tempo, High

Loudness; Slow Tempo, Low Loudness) and attitude towards store.

H1a:Background music tempo of ‘fast tempo and low loudness group’ has a statistically significant effect

on attitude towards the store.

H1b: Background music loudness of ‘fast tempo and low loudness group’ has a statistically significant

effect on attitude towards the store.

H2a:Background music tempo of ‘slow tempo and high loudness group’ has a statistically significant

effect on attitude towards the store.

H2b: Background music loudness of ‘slow tempo and high loudness group’ has a statistically significant

effect on attitude towards the store.

H3a: Background music tempo of ‘fast tempo and high loudness group’ has a statistically significant effect

on attitude towards the store.

H3b:Background music loudness of ‘fast tempo and high loudness group’ has a statistically significant

effect on attitude towards the store.

H4a: Background music tempo of ‘slow tempo, low loudness group’ has a statistically significant effect

on attitude towards the store.

H4b: Background music loudness of ‘slow tempo, low loudness group’ has a statistically significant effect

on attitude towards the store.

Research Method

3.1. Sample and Data Collection

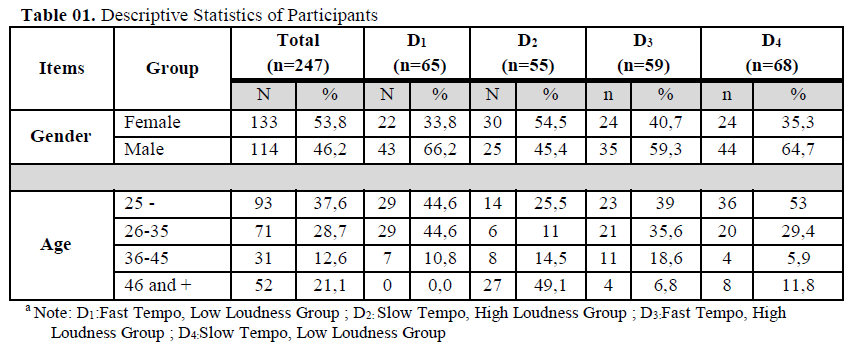

High Loudness Group ; D4:Slow Tempo, Low Loudness Group

The participants finalized shopping intention at Ak-Tac Spor and accepted to respond to survey.

114 participants (46.2 %) of the survey are men and 133 participants (53.8 %) are women. Mean age is

33.5 years. Simple random sampling was chosen as sampling method. Experimental groups have similar

characteristics. Attitude towards store as dependent variable was measured on a five-item, semantic

differential scale with anchors “bad/good”;“unfavourable/favourable”;“negative/positive”; “dislike/like”

and “outdated/modern” (Spangenberg, Crowley, & Henderson, 1996). Cronbach’s Alpha score is 0.811

for ‘attitude towards store’ questions. 7- point tempo scale (1= slow; 7= fast) and 7- point loudness scale

(1=soft; 7= loud) were followed for the evaluations of musical tempo and loudness as independent

variables in the study (Kellaris & Rice, 1993) and cronbach’s alpha was found 0.832. The obtained data

were analysed with SPSS 23.0 and hypotheses were tested with correlation analyses.

Descriptive statistical methods (average, standard deviation, frequency, percent, minimum,

maximum) and correlation analyses were utilized to evaluate research data. Conformity of normal

distribution of quantitative data was tested by Skewness and Kurtosis. Statistical significance was

accepted as p<0.05.

3.2. Compositions

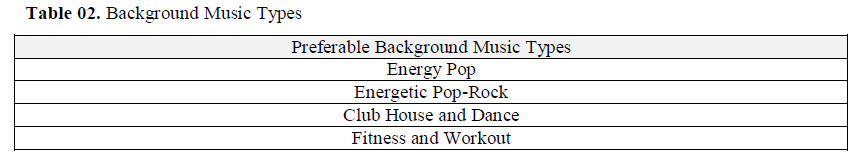

Upbeat electronic music arrangements with vocal are preferable in sporting goods retail stores in

Istanbul. Hence, slow or fast tempo expectations were influenced by favourite upbeat and energetic

sounds. This also ensured that customers in the store were not exposed to irritating repetitions of the same

compositions. Both musical genre and retail store size were influential to set loudness parameters. The

compositions at a variety of tempo and loudness used in this experiment were pretested with 69

participants to classify compositions according to tempo (fast/slow) and loudness (high/low) preferences.

Studio records of original music pieces are important for both dimensions. Especially, loudness of records

may not be standardized. Thus, pretest ensured that loudness and tempo for each music pieces were set

properly and participants were unfamiliar with melodies. These dimensions (tempo and loudness) were

checked by using digital technology periodically whilst stores were crowded in the days of experiments to

avoid confounding results. Table 2 lists the types of background music preferences in sporting goods

retail stores.

Original background music pieces were calibrated by RTP Media (Corporate Radio

Broadcasting Company).

Findings

Spearman’s rho correlation coefficients of ‘Fast Tempo and Low Loudness Group’ are given

between variables in Table 3.

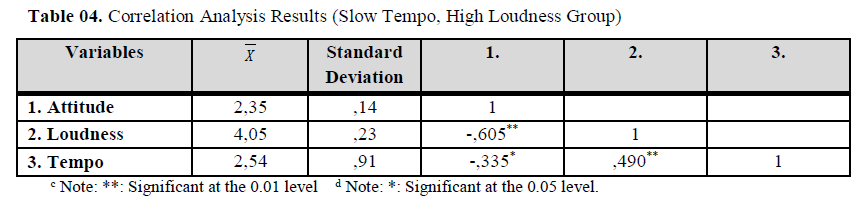

The relationship between background music tempo (r=-0,335) and attitude towards store is

statistically significant. Correlation is significant negatively at the 0.05 level. This result supports H2a.

According to the findings, the attitudes of the participants towards the store are are getting stronger as the

background music tempo is getting slower. The relationship between background music loudness (r=-

0,605) and attitude towards store is statistically significant. Correlation is significant negatively at the

0.01 level. The result supports H2b. Accordingly, as the loudness is getting higher the attitude in the store

is affected opposite. Spearman’s rho correlation coefficients of ‘Fast Tempo and High Loudness Group’

are given between variables in Table 5.

According to the results, the relationship between background music tempo (r=0,110) and attitude

towards store is not significant statistically. It is seen that the result is the same for the relationship

between loudness (r=0,203) and attitude towards store. H3a and H3b are not supported.

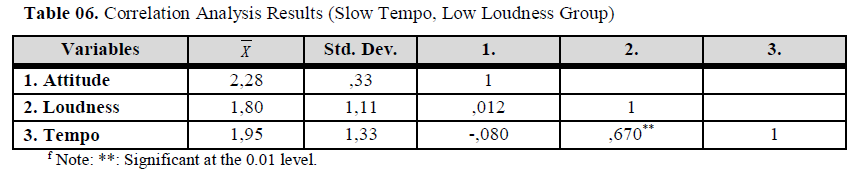

Spearman’s rho correlation coefficients of ‘Slow Tempo and Low Loudness Group’ are given between

variables in Table 6.

According to the results, the relationship between background music tempo (r=-0,080) and attitude

towards store is not significant statistically. Furthermore, statistically significant relation doesn't exist

between loudness (r=0,012) and attitude . H4a and H4b are not supported.

In Figure

Conclusion and Discussions

According to the findings obtained from the research that measured the effects of background

music tempo and loudness experimental groups on the attitude of the customers towards the store, the

effects of tempo and loudness are differentiated. Tempo of the background music has a positive effect on the customer's attitude towards the store for ‘Fast Tempo and Low Loudness Group’. Thus, the

customers’ positive attitudes towards the store are strengthened whilst tempo is faster. The majority of

‘Fast Tempo and Slow Loudness Group’ consists of participants between the ages of 25-35 and they

prefer fast tempo throughout shopping process according to the findings. Music is an important element

in brand communication, identity or architecture. Sound and music play a role in understanding the brand

and the message to be given. The relationship between brand characteristics and music is powerful according to the literature. Furthermore, background music dimensions to affect customers’ attitudes and

behaviours are frequently studied. Many studies conducted in different fields report that tempo has a

higher mobilizing effect. Thus, high tempo contributes positively to customers' store evaluation. The

result is consistent with many previous studies. However, it is seen that there is a negative correlation between ‘Slow Tempo, High Loudness Group’ and attitude towards store. The majority of ‘Slow Tempo, High Loudness Group’ consists of participants over 45. Slow tempo and high loudness evoke negative

feelings in this group. Older participants do not appreciate tempo and loudness levels. Music dimensions

have different effects on the experimental groups. Culture and demographic characteristics are the

determinants of the findings.

According to previous studies, the loudness level poses a positive effect when adjusted as

requested. High loudness versions within a band of 60 - 65 dB evoke positive reactions in ‘Slow Tempo,

High Loudness’ group. It is a really striking result. The reactions of the store customer in the ‘Slow

Tempo, High Loudness. Group’ are completely varied. Research findings state that music can be used to

influence customer attitude in practice. Store managers can evaluate tempo and volume levels of

background music in order to strengthen the positive attitudes of customers and increase the number of

customers continuously. The effect of music on potential customers is shaped by the enjoyment of

individuals, social, cultural and economic factors in the society and music familiarity. For example,

customer profile and brand identity will be critical to decide music genre and different music dimensions.

Thus, store managers should analyse atmosphere variables meticulously to make an accurate decision.

Music interacts with other atmospheric components such as lighting, odour, or colour. This

interaction can have a positive or negative effect on the attitudes and behaviours of the customers towards

store. Hereby, fresh studies can contribute to different results. Demographic characteristics of the

participants and the qualifications of the research area can determine the effects of music on sales and

consumer attitude. For example, the choice of sports retailers located in shopping malls can differentiate

the results of the research.

Music studies with different research designs illuminate the effects of music dimensions (tempo,

loudness, rhythm, mode) in store area and customer attitudes, behaviours or perceptions towards store.

Further music studies with different structural variables will contribute to the increase of the qualified

findings related to the reaction of consumers to music.

References

- Alpert, J. I.Alpert, M. I. (1990). Music influences on mood and purchase intentions.. Psychology and

- (), Marketing, 7, 109-33.

- Borges, A.Herter, M. M.Chebat, C. (2015). It was not that long!: The effects of the in-store TV screen content and consumers emotions on consumer waiting perception.. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 22, 96-106

- Burghelea, M. R.Plaias, I.El-Murad, J. (2015). The Effects of Music as an Atmospheric Variable on Consumer Behaviour in the Context of Retailing and Service Environments. No. pp. 377-392).. The Bucharest University of Economic Studies, 1

- Blazquez, M. (2014). Fashion Shopping in Multichannel Retail: The Role of Technology in Enhancing the Customer Experience.. International Journal of Electronic Commerce, 18, 97-116

- Bitner, M. J. (1992). Servicescapes: the impact of physical surrondings on customers and employees.. Journal of Marketing, 56, 57-71

- Bruner, G. C. (1990). Music, Mood and Marketing.. Journal of Marketing, 54, 94-104

- De Nisco, A.Warnaby, G. (2013). Shopping in downtown. The effect of urban environment on service quality perception and behavioural intentions.. International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management, 41, 654-670

- Donovan, R.Rossiter, J. (1982). Store atmosphere: an environmental psychology approach.. Journal of Retailing, 58, 34-57

- Farias, S. A.Aguiar, E. C.Melo, F. V. S. (2013). Store Atmospherics and Experiential Marketing: A Conceptual Framework and Research Propositions for An Extraordinary Customer Experience.. International Business Research, 2, 87-98

- Fiegel, A.Meullenet, J. F.Harrington, R. J.Humble, R.Seo, H. S. (2014). Background music genre can modulate flavor pleasantness and overall impression of food stimuli.. Appetite, 76, 144-152

- Hynes, N.Manson, S. (2016). The sound of Silence: Why music in supermarkets is just a distraction.. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 28, 171-178

- Harrington, R. J.Ottenbacher, M. C.Treuter, A. (2015). The Musicspace Model: Direct, Mediating, and Moderating Effects in the Casual Restaurant Experience.. International Journal of Hospitality & Tourism, 16, 99-121

- Herrington, J. D.Capella, L. M. (1996). Effects of Music in Service Environments: A Field Study.. The Journal Of Services Marketing, 10, 26-41

- Kellaris, J. J.Rice, R. C. (1993). The influence of tempo, loudness, and gender of listener on responses to music.. Psychology and Marketing, 10, 15-29

- Kotler, P. (1973-1974). Atmospherics as a Marketing Tool.. Journal of Retailing, 49(4), 48-64

- Mehrabian, A.Russell, J. A. (1974). An Approach to Environment Psychology

- Michel, A.Baumann, C.Gayer, L. (2017). Thank you for the music-or not? The effects of in-store music in service settings.. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 36, 21-32

- Milliman, R. E.Fugate, D. L. (1993). Atmospherics As An Emerging Influence In The Design Of Exchange Environments.. Journal of Marketing Management, 3, 66-75

- Milliman, R. E. (1982). Using Background Music to Affect the Behavior of Supermarket Shoppers.. Journal of Marketing, 46, 86-91

- Morrison, M.Beverland, M. (2003). In Research Of The Right In-Store Music.. Business Horizons, 46, 77-82

- North, A. C.Sheridan, L.Areni, C. (2016). Music Congruity Effects on Product Memory, Perception, and Choice.. Journal of Retailing, 92(1), 83-95

- Oakes, S.North, A. C. (2006). The Impact of Background Musical Tempo and Timbre Congruity Upon ad Content Recall and Affective Response.. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 20, 505-520

- Oakes, S. (2000). The Influence of The Musicspace within Service Environments.. Journal of Service Marketing, 14, 539-556

- Petruzzellis, L.Chebat, J. C.Palumbo, A. (2014). Hey Dee-Jay Let’s Play that song and keep me shopping all day long. The effect of famous bachground music on consumer shopping behavor.. Journal of marketing development and competitiveness, 8(2), 38-

- Roschk, H.Loureiro, S. M. C.Breitsohl, J. (2016). Calibrating 30 Years of Experimental Research: A Meta-Analysis of the Atmospheric Effects of Music, Scent, and Color. Ramlee, N., & Said, I. (2014). Review on Atmospheric Effects of Commercial Environment.. Procedia Social and Behaviour Sciences, 153, 426-435

- Schmitt, B. H. (1999). Experiential Marketing, How to Get Customers to Sense, Feel, Think, Act, Relate

- Soh, K. L.Jayaraman, K.Choo, L. P.Kiumarsi, S. (2015). The impact of background music on the duration of consumer stay at stores: An empirical study in Malaysia.. International Journal of Business and Society, 16(2)

- Spangenberg, E.Crowley, A. E.Henderson, P. W. (1996). Improving the store environment: Do olfactory cues affect evaluations and behaviors? Journal of Marketing, 60, 67-80

- Spence, C.Puccinelli, N. M.Grewal, D.Roggeveen, A. L. (2014). Store Atmospherics: A multisensory perspective.. Psychology and Marketing, 31(7), 472-488

- Xu, Q.Sundar, S. (2014). Lights, Camera, Music, Interaction! Interactive Persuasion in E-Commerce.. Communication Research, 41, 282-308

- Yalch, R.Spangenberg, E. (1990). Effects of Store Music on Shopping Behavior, Journal of Consumer Marketing, 7(2), 55-63

- Yamasaki, T.Yamada, K.Laukka, P. (2015). Viewing the world through the prism of music: Effects of music on perceptions of the environment.. Psychology of Music, 43, 61-74

- Yildirim, K.Cagatay, K.Hidayetoglu, L. M. (2015). The effect of age, gender and education level on customer evaluations of retail furniture store atmospheric attributes".. International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management, 43, 1-19

- Zhu, R.Meyers-Levy, J. (2005). Distinguishing between the meanings of music: When background music affects product perceptions.. Journal of Marketing Research, 42(3), 333-345

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

30 October 2019

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-070-9

Publisher

Future Academy

Volume

71

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-460

Subjects

Business, innovation, Strategic management, Leadership, Technology, Sustainability

Cite this article as:

Ovalı*, E. (2019). The Effects Of Background Music Dimensions On Customer Attitude Towards Retail Store. In M. Özşahin (Ed.), Strategic Management in an International Environment: The New Challenges for International Business and Logistics in the Age of Industry 4.0, vol 71. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 113-122). Future Academy. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2019.10.02.11