Abstract

Innovation and Sustainability is the most researched topic among many researchers and management practitioners, developers, policy-makers. In the last few decades, innovation attention has been shifting to the Global South and Bottom of the Pyramid (BoP). The Bop literature has been a cornerstone to be a transformational driver for attaining sustainability. This study focuses on a limited studied area of social innovation towards sustainable development. Surviving in a constraint environment how civil societies and social enterprise create social, economic values and opportunities through social innovation are discussed. This study is based on an inductive methodology of a case from a civil society named as “The Samdrup Jongkhar Initiative”, Dewathang, a land-locked town in South East Bhutan. This study explores how social innovation is conceptualised, designed and developed with optimal use of locally available resource to develop an appropriate product which leaves a profound impact in the lives of marginalised communities. The findings reveal that the products resulting from social innovation is appropriate to the needs of the communities. The study comprehends that social innovation entails an inclusive growth which leads to socio-economic development through the democratisation of technology. Moreover, this study also posits that social innovation is an indispensable process for humanitarian technology development and empowerment.

Keywords: Sustainable Developmentsocial innovationbricolageself-reliance

Introduction

The world’s population has reached 7.6 billion and estimated to cross 8.6 billion by 2030 (DESA, 2017). This un-planned growth poses a threat for Sustainable Development when policies, infrastructure are not well implemented thereby risking the environment. Therefore, Sustainable Development needs to be re-appraised to encompass the safety of the world around us (Griggs et al., 2013). The way our communities develop will solely depend on how we overcome the challenges related to Climate Change, Health & Sanitation, Energy, Poverty, Fighting Inequality, Infrastructure etc. In the year 25th September 2015 at the Sustainable Development Summit, The United Nations General Assembly adopted a set of 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) as Transforming our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development by committing to attain Sustainable Development in its three dimensions that is Social, Environmental and Economical aspect (UN, 2015). Following the success of Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), the new Agenda serves as a major guide for the world community to achieve Sustainable Development. The notion behind SDGs is to deal with the emerging exigency of Sustainable Development for the entire world.

Striving for Sustainability needs an approach towards innovation that installs a balance of economical, ecological and social goals. Recognizing the need for innovation for Sustainable Development, it is pertinent that technology has to play a significant role in the process of transforming the lives of communities. Successful implementation of innovation through technology always entails a social change. Schumpeter takes on innovation are a major lever force in economically transforming societies. We present a case study of a civil society where the practices of social innovation create sustainability. The study will focus on innovation and sustainability as an emerging domain of research. Innovation is becoming a transformational driver in attaining the Sustainable Development Goals by solving the economic, social and environmental issues. In the last few decades, innovation attention has been shifting to the Global South and Bottom of the Pyramid (BoP). The Bottom of the Pyramid literature as proposed by CK Prahalad represents the largest and poorest population of 2.7 billion people who still live on less than $2.50 a day and presents an unexploited area for conducting extensive research and business. The junction between poverty alleviation, innovation and sustainability provides an avenue for technological development. Much of the innovation and technology management happens under the radar, but the products or services launched have a huge impact on society and economic impact on the lives of the people. Therefore, it is pertinent to explore such development, knowledge management by organisations and agencies. Undoubtedly, civil societies and social enterprises can play a pivotal role in establishing sustainability through their operation and activities by producing benefits for society and the economy.

This study focuses on a limited studied area of social innovation towards sustainable development. Development of such innovation which promotes sustainable practices is the necessity of present times. This study draws on a qualitative case study of a civil society named Samdrup Jongkhar Initiative from Dewathang, Bhutan to elucidate the provisions and challenges of the innovation and management process, how the civil society strategizes their operation and practices for a sustainable future. The study explains how a social innovation process in a constraint environment manages the innovation process through a bricolage approach leading to development in an emerging country context. The study makes two contributions. Firstly, it illustrates how a bricolage approach is central to development. Secondly, the paper presents how the innovative activities carried out at the grassroots by the Civil Societies leads to sustainable practices. Therefore, the objective of this study is to study how social innovation enables Sustainable Development; The rest of the paper is structured as follows: section two discusses the literature review and theoretical framework. Section three presents the methodology. Section four represents the findings. Section five carries out the discussions following which there’s the conclusion.

Literature Review and Theoretical Framework

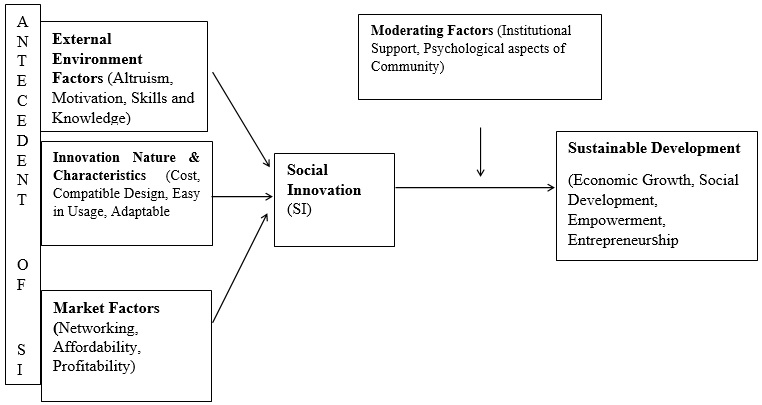

Mulgan (2006) defines social innovation as a strategy, concept which intend to address social demands and problems. According to Westley (2008) social innovation can be described as a product, service, process or even an initiative that has a great impact on the lives, resources and beliefs of any social system. Phillips (2011) posited the urgency for extensive research in the field of social change as it has taken over the field of mainstream innovation. Cajaiba-Santana (2014) highlighted that research on innovation has widely acknowledged the process to be a social activity. The differentiating facet of social innovation lies in its novelty and creating a significant response towards an appropriate output. Therefore, the dynamics of social innovation does not lie in decoding a social problem but the social change that it creates (Cajaiba-Santana, 2014). Social innovation requires attention from individuals, like in how they conceptualize, ideate, behave and value and how the interrelation between agents and stakeholders takes place (Neumeier, 2017). It is pertinent to recognize how society or people assign value or meaning to their work or actions. Henning and Hees (2010), Cajaiba-Santana (2014) discussed that social innovation is associated with skilful, systematized and goal seeking, a regulated practice which are executed by social agents aiming a social change. Bock (2016) defined social innovation as a method for seeking growth and development without government intervention where development and change lie in the hands of self-motivated and reliant actors. Mulgan (2006) cited some successful domains of social innovations which have scaled up from margins to the mainstream such as holistic health care, consumer cooperatives, housing developments, wind farms and self-help groups. Social Innovation has emerged from the burgeoning challenges in the social, environmental and demographic arena. Moreover, Social Innovation can be better recognized as a social change, a well-structured form of organisational management, creation of new products & services, the creation of a novel framework of empowerment and capacity development (Henning & Hees, 2010). Nicholls, Simon, Gabriel, and Whelan, (2015) suggested that social innovation is context-specific in nature and this further restricts access to the market. There does not still exist any standard measurement or methods to analyse the performance or impacts of social innovation. Moreover, the challenges faced by a social enterprise or civil society who undertake such innovation process are quite distinct in nature. Their end customers are mostly unseen and neglected by a traditional innovation business, which further hinders a significant market opportunity. Therefore, the societies or entrepreneurs who undertake social innovation needs to be highly innovative and be able to bridge this gap by providing affordable services and products amidst poor market, limited finance from agencies. Lately, community action has emerged to be a realm of sustainability (Seyfang & Smith, 2006). The basic principle of sustainability is the need for survival and improve the well-being of humans in harmony with the environment (Rondi, Gomez, & Collivignarelli, 2015). This paper attempts to explore sustainability issues and practice carried out by at grassroots levels such as the Civil Society, NGOs (Non-Governmental Organizations). These organizations are non-profit in nature and work selflessly, independently from the Government. Generally, much of their work is on community-based. They have a competitive edge over others by working for marginalized class (Panda, 2007). Although the impact is somewhere difficult to assess, they are the key players who initiate change and work towards the well-being of a community (Nikkhah & Redzuan, 2010). They focus primarily on welfare and development assistance by improving conditions prevailing in a region using resources from various source. Mostly these organizations are funded by international agencies or self-funded. They are sometimes responsible to bring different types of social/economic programs with the help of the Government to attenuate problems in rural areas. The Civil Society and the NGOs (Non-Governmental Organizations) are recognized as institutions who encourage community participation and empowerment. They mainly involve in raising awareness, conducting campaigns, implementing policies. Through their outreach program, they manage to win people trust. They engage themselves in solving problems from various issues by calling for suggestions. Generally, they organize street theatre for better dissemination of knowledge, message, plans and policies (Panda, 2007). Mostly they conduct a different kind of campaigns, workshops to educate and empower the community. Socially invented products and services exhibit the potential to contribute to sustainability at the grassroots. Hence, by collocating the insights form the literature and institutional theory and resource-based theory, we put forward a conceptual framework for social innovation that represents the precedent, enablers between social innovation and sustainable development. Through this framework, we will explore how organization strategies its operation, targets for sustainability. Realizing and recognizing the different factors playing a significant role in the entire mechanism around social innovation would facilitate agents, policymakers, societies, communities to better discern the needs and role in promoting more social innovation (Figure

Research Method

The study employs a case study method that involves participatory and interactive process, field observations on the process of social innovation development, adoption and diffusion by the vulnerable communities with the help of the Civil Society. The approach followed in this study is a qualitative coupled with an ethnographic method. The particular site was chosen for the study because of the innovative practices the communities followed towards a sustainable future. These criteria were followed for selecting the case: first, the chosen case required to have a small-scaled technology specific to a given region. Second, community and local civil society intervention was needed to provide appropriate product in a specific context. Third, the case had to be scalable and sustainable in its functioning, it had to be empowering to the community and at the same time be commercially viable. Data were gathered primarily through interviews with the community and report materials (international report) published on SJI journals; this multi-level search assured the accuracy of the findings. Further, data were analysed applying data triangulation (Yin, 2003), whereby the researchers also looked for new possibilities. It took a one-month search of web-articles, reports, to find out organizations which referred to the practices of social innovation and Sustainability being carried out with a social, economic and environmental impact. We carried out data collection from the countries in the Global South mainly from the Indian and Bhutan Sub-continent, which acts as a huge reservoir of innovation at the grassroots. From a large set of references, we found out appropriate cross-references of a small set of organizations, which were covered by the media has done extensive work. The search led us to the discovery of Samdrup Jongkhar Initaitive (SJI), a civil society in Dewathang, Bhutan which through its extensive social practices and innovative activities empowers the communities to strive for a sustainable future.

The study is established on the primary and secondary inputs of an interview with community members and staff of SJI. Upon reaching the Civil Society, the first phase involved interactions with SJI staff members in order to understand their activities meant to improve the well-being of the community at large. The second stage involved the selection and exploration of technology introduced by SJI with the help of institutional support and community members, international organizations. Through SJI, the researchers also reached out to the community/villages where SJI carried out direct interventions. The communities/villages chosen were selected randomly focusing primarily on places where the practice of energy and waste management was functional; where the members understood its working and functions and operated on a regularly basis. Finally, the researchers deliberately selected two innovations because of its civic society readiness, and their willingness to allow the researchers to study the technology development in the vulnerable communities. The data was gathered by carrying out semi-structured interviews and direct observations through which the researchers had the opportunity to witness the entire working mechanism and innovations. The interviews were conducted in July,2018 using English as the primary medium of communication. The interviewed lasted for an hour or two and were mostly open-ended in nature; additionally, these interviews were recorded with due permission from the participants. After the completion of interviews, they were transcribed; thereafter, open coding was used to find out major themes linked to the concept of social innovation and sustainability (i.e. cost, capacity development, indigenous skills, accessibility, gender considerations), which served as the prime purpose of our framework. Further, the grounded theory approach was used (Gioia, Corley, & Hamilton, 2013), to develop inference of the qualitative data such as the interviews and semi-structured interview

Case Discussion

The area of intervention for this study was Samdrup Jongkhar Initiative (SJI), a civic society located in Dewathang, Samdrup Jongkhar district in the south-eastern part of Bhutan. It is the only major civic society initiative in Dewathang, under the aegis of Lhomon society which started in the year 2010 inspired by the principles of its spiritual leader Dzonsar Jamyang Khyentse Rinpoche. SJI’s prime focus was to improve the living standards in the district in an eco-friendly manner, establishing food security and self-sufficiency while conserving the environment and strengthening communities (Samdrup Jongkhar Initiative, 2018). These goals of SJI are aligned with those of Bhutan’s national principle, committed towards GNH-based development. The key activities of SJI includes for instance training on best agricultural practices, promoting lead farmer approach and farmer-to-farmer extension program; creation and development of model farmer and farm; revival and promotion of traditional cereal crops with value addition; solar driers and rain-water harvesting earmarking; pilot impact areas; formation of vegetable groups; preservation and promotion of local knowledge & practices; developing community seed bank and developing knowledge products. SJI dreams of building an own eco-village where the concept of community vitality, software aspects of technology, leadership should be more action driven. SJI primarily works on three areas, i.e. organic agriculture, sustainable waste management and education, employing appropriate technology. Several technologies thought to be potentially appropriate have been proposed and were, adopted by SJI, in various villages of Dewathang. Below discussed are two examples of innovation which led the social practices in the civil society and community towards sustainability:

Solar Drying of Cereal, Crops, Fruits and Vegetables (SDR)

The case of Solar Drying in Menchari region of Dewathang community elucidates the social project undertaken by the SJI in the village. The application of solar drier is an example of innovation attempt to develop appropriate technology for drying up fruits, vegetables in the Menchari Region. The Menchari village has about 23 households and it is one of the poorest and neglected communities in the district. The farmers in this region grow paddy, mustard, legumes, millet etc. Due to heavy precipitation and lack of transportation facility, the farmers produce crops for their self-consumption. Drying vegetables is an old tradition in the community, the farmers dried vegetables and fruits in the open, which further lead to mould formation and contamination because of birds and animals. Therefore, the community farmers ideated on a solar drying, a better alternative than drying in the open as it would ensure uniform drying while retaining the nutrient value. A UV sheet would cover the solar dryers. Thus the farmers wouldn't have to be present during the drying process and may continue with their farm work.

A working member of SJI told us that the development of Solar Drier traces back to 2011 when a collaborative project was undertaken by SJI and the Centre for Appropriate Technology at Jigme Namgyal Polytechnic (JNP), A Diploma College in Dewathang, to study the potential application of solar dryer technology (Samdrup Jongkhar Initiative, 2018). In the year 2011, directors from the Barli Development Institute for rural women in Madhya Pradesh, India were invited to give a presentation to the students, staff, and farmer representatives on low-cost solar drying technologies. The presentation was well received by the audience, and the faculties from JNP agreed to design a locally appropriate solar dryer unit, for which the farmers would be trained to acclimatize themselves with the working and operations of the machine. As the project was initiated by SJI and funded by the International Development Research Centre (IRDC, Canada), one faculty member from JNP and six villagers undertook training in Madhya Pradesh, India for manufacturing the solar dryer. By the end of 2011, the local solar dryer was built, post which the National Post Harvest Centre (NHPC) of the Ministry of Agriculture and Forests, Bhutan evaluated the technical feasibility of the dryer. The dryer was found to be effective for drying fresh produce, providing an enabling environment during the day while preventing condensation during the night. The dried products were free from dust and mould. The materials used for constructing the Solar Dryer included CGI sheet, solar panel, dry cell battery, timber and bamboo, drying trays, labour charge, CPU fan, Voltage controller and fuse, UV plastic sheet, flexible wire, red oxide, black paint, GI wire nail, fevicol and ordinary plastic; the total cost of manufacturing the machine amounted to Nu. 15260 (i.e. $215.99). During the design and implementation phase, improving the capacity of communities was given importance so that they don’t depend on any external help. Many residents of the village came and participated in the on-site fabrication process training, and finally, the solar drier came into use. Additionally, the solar drier project received funding for implementing and disseminating the project in. Menchari and other villages too from the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) and the Gross National Happiness Commission-initiated Rural Economy Advancement Program (REAP) [Samdrup Jongkhar Initiative, 2018]. We observed from our visits how the implementation of Solar drier has made community self-reliant as they can dry and store crops in the off-season and can later sell it to markets which later improves their income (Figure

Zero Waste Management (ZWR)

Minimization of waste and waste management practice is strictly done in Dewathang District. Use of plastic is completely banned in this region. The SJI aims for waste reduction in different festivals, ceremonies and events. The waste management practice includes waste segregation, developing pilot zero waste villages, creating zero waste crafts cooperative, and provide zero waste training manuals (Samdrup Jongkhar Initiative, 2018) by cleaning of a dump site. SJI introduced an innovative method (Zero Waste Craft) towards controlling waste management in Samdrup Jongkhar. This not only created a livelihood for many women but also changed the perception of how waste is looked at. The researchers visited the house of a middle-aged woman who is a housewife and illiterate, but competent enough to earn a living for her family. The woman showed how she and the other women in the villages weave baskets, bags using freely available plastic (generally plastic bottles) that were being dumped in the community. Using discarded plastic bottles and stripping them into threads through a cutter the strips are woven into the loom. The recycling activity of plastic waste diversified into income generation opportunities for women of the village, whereby they sold the recycled goods in the market at a reasonable price. For these women, cutting down the bottle into strips and weaving them in the installed loom is a kind of social innovation. The entire process of converting waste into the final product takes about a day or two. The looms are installed in their homes as a part of their tradition, so this saves time and extra labour. These women produce about 10-15 bags per day. According to a Working Staff of SJI, the bags and baskets, which are final recycled products have a huge market demand; this gives women an extra income for sustenance, leading them to be self-reliant. This entire procedure of turning waste into a valuable resource results in conservation of the environment and prevents waste accumulation in the community (Figure

Data Analysis

We analysed the data with an intent to identify themes, content and issues. The data recorded form the interview and observations were evaluated with the help of an NVivo 9 Software which is mostly employed to interprete a qualitative dataset. Data analysis was done with the help of NVivo 12 software, which is largely employed to analyse complex, heterogeneous qualitative data. Subsequently, during the analysis, we followed the Grounded theory approach proposed by Gioia et al. (2013). As proposed by Gioia and his colleagues (2013) we used three steps: first, the transcript was segregated to statements or facts and assembled in categories which are more theory-centric, we name this as First-order coding. In the next step, we tried to explore the relationship between the first order- codes, and to get a clarity of themes, which lead to the development of second-order category; this category was more abstract and conventional. It was more of an inductive approach, which explored construct rich in theory. In the final step, the construct was positioned and a core dimension was identified, validating the construct with existing literature. This reflected the dynamics behind AT development and implementation; this process has been named as Aggregate Core Dimension. Below is the given Table

Findings

This section presents the empirical findings. The two aggregate dimensions which emerge from the data structure are Process of Bricolage Practice and Sustainable Driven Practice.

Process of Bricolage Practice

The first aggregate dimension that arises from the data is the Process of Bricolage Practice. The idea of Bricolage was coined by the French Anthropologist Levy-Strauss (1966) to explain the condition of resource scarcity within organization. Since then Bricolage has been discussed in a diverse range of context to illustrate the resource creation and entrepreneurship. Garud and Karnoe (2003) highlighted that Bricolage is being used as a legit approach for innovation and development process. Baker and Nelson (2005) further developed Levi-Strauss ideology and highlighted significant traits of Bricolage. Firstly, an individual or organization engages in bricolage by in genuinely combining the resources at hand and using them in a new setting, deviating substantively form their intended usage. It includes adding meaning to resources which otherwise would have been treated useless or inadequate. Baker and Nelson (2005) expanded the notion that it is the creation of a new from old or creating "something from nothing.

The key input to the practice of bricolage in the context of SDR and ZWM was making use of available resources and local materials with indigenous knowledge so that cost of production and maintenance is low, which in turn would open the markets for the local products outside Dewathang region, and thereby provide a new source of income. According to Project Staff of SJI, the novelty of SDR is to produce food on one own term eliminating dependency on foreign countries, increasing variety and diversity of crops and let the community decide to what they consume making a fresh, healthy and local produce. Moreover, SJI conducts community mapping program, demonstrations and workshop to sensitize community regarding various issues and how they can make a living of their own eliminating dependency.

Sustainable Driven Practice

The second aggregate dimension is a sustainable-driven practice which explains the intention of the civil society and communities to deliver appropriate, eco-friendly, economic and social benefits. Sustainability is at the heart of the organizations at the grassroots which further focus on innovative practices and development approaches. The respondents responded that they are motivated by the urgent need to improve their economic state and an intrinsic desire to empower the communities.

In the above-discussed case of the SDR and ZWM, Economic development from the lens of Sustainable Development include aspects such as profit-generation, increase in revenue, stability and local entrepreneurship. The use of SDR eliminated the dependency of the community from an external source and increased self-reliance of the community. According to the Project Director of SJI, storing and growing crops through SDR leads to self-consumption and this is sustainability for them. Similarly, ZWM led to the creation of jobs which improved the economic condition of women in the village and gave them a source of income to sustain their homes. Social development perspective includes aspects like quality of human life, employment, security etc. The SDR improved the lives of marginalized people they can sell their produce outside Dewathang which gave them a sense of security, promoted gender equity as women solar engineers trained village members for fabricating and installing the solar drier. Ecological development refers to the conservation of energy and renewable resources, bio-diversity preservation. SDR is energy efficient, and ZWM reduces waste accumulation. Since the innovation in both the cases advocated local and few resources, therefore energy, cost and resources were conserved, which in turn has a positive societal and economic impact on the lives of the communities.

Conclusion and Discussions

The case discussed gives a strong sense of the practice of social innovation along with the sustainability. Any innovation and technological change in Bhutan exclusively comes in the form of imported machines or developed outside and adapted here by the organizations and communities. Although the Govt. provides free training and learning to the people through the workshop conducted by the Civil society, community discards it when they find any product or technology to be unusable. Innovation and technology management in developing countries like Bhutan is lagging far behind other developing countries of the world due to weak infrastructure, unskilled labour, research institutes, higher educational institutes’ and absence of business models. Nevertheless, Civil Society like SJI strategizes their working to improve the lives of marginalized communities through various programmes. The challenge lies in formalizing the initiatives and devising a comprehensive framework. Research at the junction between innovation and sustainable development at the grassroots has various implications and is at its nascent stages. The Bricolage innovative activities initiated by the civic societies and a few villagers from the community generates localized, easy, simple, appropriate and affordable products/services. The dynamics between sustainability and technology involves various innovation and collaboration which can be understood as a necessity to support different kinds of actions and activities. Innovation can thereby be understood as an interplay among various actors. However, studies on innovation in an informal context or at a community level are scarce. The presence of institutional and transactional constraints impedes the development process. The findings indicated that implications for development would benefit from a community engagement, co-designing and removing social stigma through various awareness program. The data for this study was restricted to one civic society within a particular country. Therefore, a further generalization of the results and analysis require a large analysis of cases. Further studies should acknowledge and examine different factors that affect the development and implementation process towards sustainability. Future studies can empirically test the framework to find out the effect and influence of factor over other.

Acknowledgments

The authors would sincerely like to thank THE SAMDRUP JONGHAR INITIATIVE, DEWATHANG, BHUTAN for helping us and letting us reach out to the communities and carry out our research.

References

- Baker, T., & Nelson, R. E. (2005). Creating something from nothing: Resource construction through entrepreneurial bricolage. Administrative science quarterly, 50(3), 329-366.

- Bock, B. B. (2016). Rural marginalisation and the role of social innovation; a turn towards nexogenous development and rural reconnection. Sociologia Ruralis, 56(4), 552-573.

- Cajaiba-Santana, G. (2014). Social innovation: Moving the field forward. A conceptual framework. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 82, 42-51.

- DESA, U. (2017). World population prospects, the 2017 Revision, Volume I: comprehensive tables. New York United Nations Department of Economic & Social Affairs.

- Garud, R., & Karnøe, P. (2003). Bricolage versus breakthrough: distributed and embedded agency in technology entrepreneurship. Research policy, 32(2), 277-300.

- Gioia, D. A., Corley, K. G., & Hamilton, A. L. (2013). Seeking qualitative rigor in inductive research: Notes on the Gioia methodology. Organizational research methods, 16(1), 15-31.

- Griggs, D., Stafford-Smith, M., Gaffney, O., Rockström, J., Öhman, M. C., Shyamsundar, P., … & Noble, I. (2013). Policy: Sustainable development goals for people and planet. Nature, 495(7441), 305.

- Henning, I. K., & Hees, F. (2010). Studies for Innovation in a Modern Working Environment–International Monitoring (www. international monitoring. com) Department of Information Management in Mech. Engineering.

- Levi-Strauss, C. (1966). The savage mind. University of Chicago Press.

- Mulgan, G. (2006). The process of social innovation. Innovations: technology, governance, globalization, 1(2), 145-162.

- Neumeier, S. (2017). Social innovation in rural development: identifying the keyfactors of success. The geographical journal, 183(1), 34-46.

- Nicholls, A., Simon, J., Gabriel, M., & Whelan, C. (Eds.). (2015). New frontiers in social innovation research. Springer.

- Nikkhah, H. A., & Redzuan, M. R. B. (2010). The role of NGOs in promoting empowerment for sustainable community development. Journal of Human Ecology, 30(2), 85-92.

- Panda, B. (2007). Top down or bottom up? A study of grassroots NGOs’ approach. Journal of Health Management, 9(2), 257-273.

- Phillips, F. (2011). The state of technological and social change: Impressions. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 78(6), 1072-1078.

- Samdrup Jongkhar Initiative (2018). Retrieved from www.sji.bt/ (Accessed on 18th August, 2018).

- Seyfang, G., & Smith, A. (2006). Community action: a neglected site of innovation for sustainable development? (No. 06-10). CSERGE Working Paper EDM.

- Sorlini, S., Rondi, L., Pollmann Gomez, A., & Collivignarelli, C. (2015). Appropriate Technologies For Drinking Water Treatment In Mediterranean Countries. Environmental Engineering & Management Journal (EEMJ), 14(7).

- United Nations (UN). (2015). Transforming our world: The 2030 agenda for sustainable development. New York: United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs.

- Westley, F. (2008). The Social Innovation Dynamic, Social Innovation Generation, University of Waterloo.

- Yin, R. K. (2003). Case study research: Design and methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

30 October 2019

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-070-9

Publisher

Future Academy

Volume

71

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-460

Subjects

Business, innovation, Strategic management, Leadership, Technology, Sustainability

Cite this article as:

Patnaik*, J., & Bhomick, B. (2019). Innovation Management In A Constraint Environment: Challenges In The Age Of Sustainability. In M. Özşahin (Ed.), Strategic Management in an International Environment: The New Challenges for International Business and Logistics in the Age of Industry 4.0, vol 71. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 101-112). Future Academy. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2019.10.02.10