Abstract

Public stigmatization towards people with mental illness is a common issue in Asian culture. People with mental illness have been treated with disgrace and shame even though numerous anti-stigma efforts have been developed at a national and even international level. Stigmatization promotes public rejection and discrimination. Past studies revealed contradicting results on the role of education and gender on public stigmatization of mental illness. In line with this, the present study aimed to identify whether factors such as education and gender play a role in this phenomenon. A survey was conducted based on 180 adult respondents in Kampar town, Perak. The Community Attitudes of the Mentally III Scale was used to measure public stigmatization towards mental illness. The data was analysed quantitatively using SPSS version 20. The findings of the present study revealed that unlike gender, the level of education was identified to have significant influence on public stigmatization to people with mental illness. In view of the education level, the results indicated that both genders portrayed lower stigmatization when the level of education is higher. Public stigmatization was found common among those participants with primary level of education as compared with those with tertiary education. The present study suggests an integrated need for prevention and intervention programmes to combat public stigmatization towards mental illness. Preventive programmes involving the participation of the local community, policy makers and schools could be implemented to primary school students to cultivate a positive conceptualisation of mental illness in the early developmental stage.

Keywords: Education levelgendermental illnesspreventionpublic stigmatization

Introduction

Mental illness is generally classified as a mental state or disorder which brings effect on an individual’s emotion, behaviour and routine (World Health Report, 2001). At present days, mental illnesses are emerging as serious health threats in both developed and developing nations. This issue is more common now compared to yesteryears as the post effect of people undergoing strain to chase for wealth and fit the high living standard. The city living and poor mental health are important factors contributing to the rising number of mental illness cases globally (Fitzgerald, Rose, & Singh, 2016). In Malaysia, national surveys in year 2013 warned that 10% of Malaysians will be affected by mental illness by the year 2020 (Lakshiny, 2015). Furthermore, there were about 400,227 patients in Malaysia registered in public hospitals in regards to mental illness with 2,000 new cases of mental illness being reported every year (The Star, July 1, 2016).

Whilst the rate of mental illness is increasing, there is still an existing attitude within most societies to view mentally ill people as threatening and this attitude frequently fosters public stigmatization. Besides struggling with these symptoms, mentally ill people also face other challenges which are caused by society’s misunderstandings about mental disorders. Public stigmatization is defined as a label attached by society or a set of adverse attitudes and beliefs that prompt an individual to fear and reject a group of people (Corrigan & Shapiro, 2010). It was found that people with mental illnesses are among the most stigmatized people of all groups (Stuart & Arboleda-Flórez, 2012). Stigmatization crops up due to inappropriate labelling, negative stereotyping and prejudiced behaviour towards individuals with some mental disabilities. Stigmatization has wide-reaching effects towards people with mental illness as it promotes rejection and suboptimal interaction which will in due course, causes discrimination.

Generally, mental illness is still approached with adverse attitudes and rejection by the majority of society. Existing literature shows a few indicators that contribute to the stigmatization towards mental illness and the most commonly mentioned predictor is gender (Khan, Kausar, Khalid, & Farooq, 2015; Ward, Wiltshire, Detry, & Brown, 2013; Williams & Pow, 2007; Wirth & Bodenhausen, 2009). However, current writings have contradictory evidence in which stigmatization is present in both genders. A study among students in Wilmington stated that gender influences the portrayal of stigma towards mental illness. Results showed that males showed a negative attitude and involved in more stigmatization compared to females (Lowder, 2007). It was also found that gender differences that were present in their attitudes towards mental illness was due to the differences in their mental health literacy. It indicated that males knew less about mental illness and therefore they develop stigma towards mental illness (Swami, 2012). Researchers also attributed females’ supportive attitude towards mental illness to the nurturing role of female as a mother or wife (Lowder, 2007). Likewise, the findings of Ward et al., (2013) also stated that African American males showed higher rate of discrimination towards mentally ill people as they perceived mental illness as dangerous. A much older study also found that females tend to hold less stereotyping views towards mental illness in comparison to males. This study was conducted among 388 secondary school students in Hong Kong. The study found males tend to have more separatism and labelling behaviours (Ng & Chan, 2000). However, on the other hand, another research done later among students stated that there were no gender differences in their attitudes towards mental illness. Both males and females reported to have similar perception and attitude towards mentally ill people (Ukpong & Abasiubong, 2010). Hence, mixed findings of the earlier studies on gender differences make the current research crucial to find out the exact scenario.

Additionally, one’s education level is believed to also contribute to mental illness stigmatization. Individuals with less knowledge and lower education background has higher tendency to avoid people with mental illness. A study among Scottish teenagers indicated that the sample with weaker education support have more negative attitudes towards mental health (Williams & Pow, 2007). People with secondary and tertiary education were less authoritarian and less socially restrictive towards mental illness. Higher education equipped an individual with more ethics and it makes the difference in their attitude towards mental illness (Barke, Nyarko, & Klecha, 2011). The findings were consistent with a classic study which strongly emphasized that an individual with no education or basic education has the highest stigma towards mental illness and disabilities (Wolff, Pathare, Craig, & Leff, 1996). However, Ukpong and Abasiubong (2010) in their study postulated that education level does not directly determine the attitude or level of stigma portrayed by an individual thus contradicting the earlier study which showed a significant study between education level and stigmatization.

Past research provided a mixed review on the factors contributing to public stigmatization. As public stigmatization is an issue that should be controlled to avoid any further social issues, numerous anti-stigma efforts have been developed at local, national, and international levels. It was hypothesized that gender and education level play a role in the public stigmatization towards mental illness. The findings of the study could be useful for the local and international authorities by discovering where they need to start their interventions to combat public stigmatization and reduce the social distance between general public and mentally ill people. By having this changing determinant of public stigmatization, this piece of research was conducted in an attempt to further understand the interaction effects of gender in the relationship between level of education and public stigmatization towards mental illness.

Furthermore, a study for example has shown that Western educators use different methods to educate on stigmatisation in comparison with Eastern educators (Kayama, Haight, Ku, Cho, & Lee, 2017). While another study showed that public stigmatisation may not be culture specific or religion specific (Yeo & Chu, 2017). The indecisive nature on the influence of culture towards public stigmatisation prompted the current study to focus on the interactional effect of education and gender on public stigmatisation towards Malaysian population in general as education may help in changing the public attitudes. Additionally, mental illness is common among all ethnicities and there are no prevalence rate differences between races, religion and culture.

Problem Statement

Mental illness is generally classified as a mental state or disorder which brings effect on an individual’s emotion, behaviour and routine (World Health Report, 2001). In Malaysia, national surveys in year 2013 warned that 10% of Malaysians will be affected by mental illness by the year 2020 (Lakshiny, 2015). Whilst the rate of mental illness is increasing, there still exist attitudes within most societies to treat mentally ill people as threatening and this attitude frequently foster public stigmatization.

Public stigmatization is considered as a label attached by society or a set of adverse attitudes and beliefs that prompt an individual to fear and reject a group of people (Corrigan & Shapiro, 2010). Stigmatizing cropped out due to an inappropriate labelling, negative stereotyping and prejudiced behaviour towards individuals with some mental disabilities. Stigmatizing has wide-reaching effect towards people with mental illness as it promotes rejection and suboptimal interaction which will in due course, causes discrimination.

Current writings have contradictory evidence in which stigmatization present in both gender. A study among students in Wilmington stated that gender influences the stigma portrayal towards mental illness. It was also found that the gender differences occurred in their attitudes due to the differences in their mental health literacy where females tend to hold lesser stereotyping view towards mental illness in comparison to males. However, research done later among students stated that there were no gender differences in their attitudes towards mental illness. Hence, mixed findings of the earlier studies on gender differences make the current research crucial to find out the exact scenario.

Education level is believed to also contribute to mental illness stigmatization. People with secondary and tertiary education were less authoritarian and less social restrictive towards mental illness However, study postulated that education level does not directly determine the attitude or level of stigma portrayed by an individual thus contradicting earlier study which showed a significant study between education level and stigmatization.

Research Questions

-

Does gender and education level play a role in the public stigmatization towards mental illness?

-

What is the interaction effect of education and gender on public stigmatisation towards mental illness?

Purpose of the Study

Past research provided a mixed review on the factors contributes to public stigmatization. As public stigmatization is an issue that should be controlled to avoid any further social issues, numerous anti-stigma efforts have been developed at local, national, and international levels. Additionally, the indecisive nature on the influence of culture towards public stigmatisation prompts the current research to focus on the interactional effect of education and gender on public stigmatisation The findings of the study could be useful for the local and international authorities to discover where they need to start their interventions to combat public stigmatization and reduce the social distance between general public and mentally ill people.

Research Methods

Participants and Procedure

A total of 180 adults from Kampar, Perak, Malaysia were invited to participate in this study. This is because Kampar consists of population of diversified age group and educational level. Convenience sampling was used to recruit the participants. Equal sample size was framed in order to compare between groups on their stigmatization towards mental illness. Several personal characteristics such as age group and gender were fixed. As such, a total of 60 participants (30 males and 30 females) were recruited from each age group (Young adult: 20 – 30 years; Middle adult: 31 – 59 years; Older adult: 60 and above).

Measures

The research questionnaire used paper and pencil method which consists of two parts. The first part comprises of demographic information of respondents such as age, gender and level of education. The second part consists of the Community Attitudes of the Mentally III Scale (CAMI; Taylor & Dear, 1981) was used to assess public stigmatization towards mental illness. CAMI consists of 40 items measuring stigma towards mental illness with four sub-scales, namely benevolence, community mental health ideology, authoritarian and social restrictiveness. Respondents required to state their opinion based on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). High score indicates more stigmas towards mental illness. The Cronbach alpha reliability for the scale was .830 for this study. CAMI had been widely utilized by researchers conducting research on public attitudes toward the mentally ill in countries like Southern Ghana, New Jersey, Beijing, Taiwan, Nigeria as well as in Malaysia (Barke, Nyarko, & Klecha, 2011; Sevigny et al., 1999; Song, Chang, Shih, & Yang, 2005; Ukpong & Abasiubong, 2010; Zubaidah & Norfazilah, 2014). In addition, the measurement had a high correlation among the four subscales which is 0.88 (Link, Yang, Phelan, & Collins, 2004). According to Taylor and Dear (1981), the three subscales had high reliability value of Cronbach Alpha with benevolence 0.76, Social restrictiveness 0.80 and community mental health ideology 0.88, while authoritarian has a reliability range from 0.69-0.88 where the construct validity showed a positive outcome as well.

Data Analysis

SPSS version 20 was used to analysis the data of the study. Two-way ANOVA interaction analysis was subjected to investigate the interaction effect of gender in the relationship between respondents’ educational level and stigmatization towards mental illness. This technique allows us to look at the single and joint effect of the two independent variables on the dependent variable (Pallant, 2013).

Findings

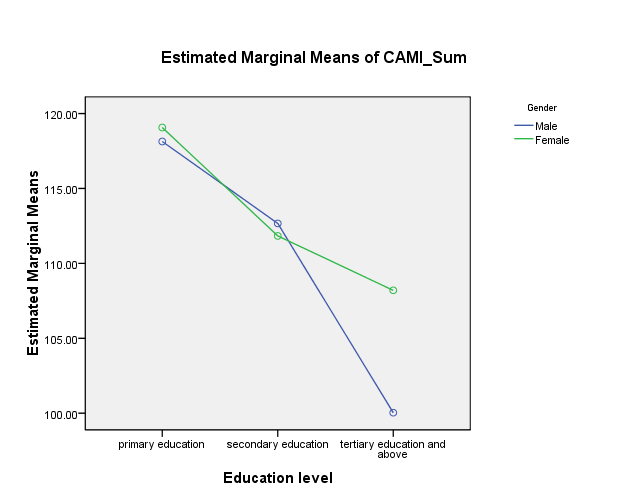

A Two-way ANOVA interaction test was used to compare the score of perceived public stigmatization toward mental illness of six groups of participants: (a) males with primary education, (b) males with secondary education, (c) males with tertiary education, (d) females with primary education, (E) females with secondary education, (f) females with tertiary education.

Table

Figure

Conclusion

The current findings found that educational level is found to have a significant effect on public stigmatisation towards mental illness, which is consistent with Barke et al., (2011); Williams and Pow (2007); Wolff et al., (1996); and inconsistent with Ukpong and Abasiubong (2010). Educational level seems to influence one’s public stigmatisation towards mental illness as knowledge makes an individual be better informed and in turn reduces stigmatisation (Audu, Idris, Olisah, & Sheikh, 2011; Ronzoni, Dogra, Omigbodun, Bella, & Atitola, 2010). When one has higher levels of education, they tend to use multiple resources to understand complicated information about mental illness (Kidane, 2014). While the current study focused only on educational level, education attainment is significantly correlated with knowledge on mental illness, which is associated with benevolent attitude towards mental illness (Aghanwa, 2004). For example, community volunteer workers who participated in educational programme raising awareness on mental illness significantly improved their attitudes towards mental illness (Abayomi, Adelufosi, & Olajide, 2013).

In the current study, it was found that gender has no influence on stigmatisation towards mental illness. This is consistent with the findings found by Lowder (2007); Ward et al., (2013), and similar with Ukpong and Abasiubong (2010). Gender is found to interact with stigmatisation based on gender scripts or patriarchal views or gender stereotypes (Khan, Kausar, Khalid, & Farooq, 2015; Wirth & Bodenhausen, 2009; World Health Organisation, n.d. as cited in Shimmin, 2009). Females tend to experience mental illness related to stigmatisation because of the view that females tend to be more psychologically imbalanced (Khan et al., 2015). Thus, gender scripts tend to be subscribed to mental illness that is more gender-typical (Wirth & Bodenhausen, 2009). This means that there are gender-specific expectations towards certain mental illness. For an example, it is acceptable for a female to show depressive symptoms whereas it is considered as poor adjustment when a male exhibits these symptoms (Reichert, 2012). However, it is possible that the respondents in this study do not prescribe to such views. Besides, it was also found that parent’s education could influence in how gender could influence public stigmatisation. When parents are more educated, their children also tend to be more positive towards mental illness (Savrun et al., 2007).

Although gender does not have a significant influence, the females in the study do show lower stigmatisation when they are more educated. While knowledge gives awareness, females are generally more instinctual in regards to emotions, thus more open to using psychological labels (Robles-Garcia, Fresan, Berlanga, & Martinez, 2013). Hence, females equipped with the knowledge and their nature of being more tolerant tend to show more positive attitudes towards mental illness.

The current results strengthen the need to spread knowledge on mental illness to combat stigmatisation. Thus policy makers may still invest in having a good campaign to raise public knowledge on mental illness. This is because policy makers can be a contributing effect in combating stigma by investing in such measures (Arthur, Hickling, Robertson-Hickling, Haynes-Robinson, Abel, & Whitley, 2010). The effect of such campaign or intervention definitely improves one's’ attitudes towards those who are mentally ill (Abayomi et al., 2013). However, knowledge can be a double-edged sword as information about mental illness promotes social distance. Hence, campaigns raising awareness towards mental illness should also accommodate other strategies as well (Lauber, Nordt, Falcato, & Rossler, 2004). Strategies may include a nationwide television or radio advertising campaign, mental health day, public speaking engagement by people who has experienced mental health illness. The media plays an important role in any movement for change as they determine public attitudes toward mental illness.

The findings of this study where stigmatization towards mental illness is higher among those with primary education is consistent with studies which showed that those which received primary education seemed to have developed negative conceptualisation of mental illness (Corringan & Watson, 2007; Hinshaw, 2007; Reavely & Jorm, 2011). Thus empowering students in primary school level with mental health literacy program is essential as they are able to develop cognitive ability to conceptualise differences between “good” and “bad” during this cognitive developmental stage (Corringan & Watson, 2007). The introduction of anti-stigma campaigns and interventions could help to shape the sensitive and empathic attitudes young students towards individuals affected by mental illness. School-based anti-stigma programmes which include strategies such as talks, drama, games, quizzes, storytelling and exhibitions might help to facilitate social inclusion, reducing conflicts, prejudice and discrimination. Given the advancement of information technology the use of social media, such as internet and social based communication is an increasing relevant platform to promote anti-stigma programmes.

School can be an important medium for mental health promotion, combating stigma associated with mental illness and possibly providing early prevention and on-going care. Stigma associated with mental illness can affect how the teachers, peers and classmates treat individuals with mental disorders. Anti-stigma school activities can reach people of all social levels from teachers, administrators to parents but most important to the students themselves. Classroom teachers play an important role in identifying and assessing problematic students and referring them to school counsellors for professional help (Kok & Low, 2017). School staff and teachers may help to influence the adolescents’ attitudes to mental issues by organising social visits to mental health rehabilitation centres. During these social visits young adolescent will be given the opportunity to interact with residents who have recovered from their mental illness. Through the sharing of experience and discussion of the challenges encountered by these recovered patients it may change the adolescents’ negative self – belief and perceptions of mental illness. Contact intervention may also involve sharing of experiences by caregivers of mental illness patients. This intergroup interaction may create better understanding of the challenges and problems encountered by family with mental illness siblings. The current study only employed respondents from one particular area in Malaysia, which may limit the results of the current study. Future research may include respondents from wider demographics such as from rural and urban areas. Additionally, this research only assesses the differences between gender and education level lacking in showing the relationship between other demographic variables. Future studies should consider factors such as culture and ethnicity which are important influential factors on stigmatization as they affect the individual's’ perception of mental illness.

While the current studies gave an insight to the need of educating the general public, the current research did not explore other variables apart from demographic in regards to public stigmatisation such as gender roles, parental education. Besides, the small sample size is another weakness of the study where the result could not be generalized to the whole population of Kampar. As the study did not assess the relationship between the demographic variables it did not provide more information to further understand the reasons for stigmatization towards mental illness among the people in this small town.

Despite these limitations, the current study has substantiated that promoting positive attitude towards mental illness via knowledge dissemination is vital. The current study has opened a platform to further look into effective ways in propagating information on mental illness. The findings of the study may be useful for mental health professionals to target their anti-stigmatization programme and organise intervention activities for school children.

Acknowledgments

Conflict of Interest. The authors declared that there is no conflict of interest among the parties of concerned. Informed Consent. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in this study.

References

- Abayomi, O., Adelufosi, A. O., & Olajide, A. (2013). Changing attitude to mental illness among community mental health volunteers in south-western Nigeria. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 59(6), 609-612. DOI:

- Aghanwa, H. S. (2004). Attitude toward and knowledge about mental illness in Fiji Islands. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 50(4), 361-375. DOI:

- Arthur, C. M., Hickling, F. W., Robertson-Hickling, H., Haynes-Robinson, T., Abel, W., & Whitley, R. (2010). “Mad, sick, head nuh good”: Mental illness stigma in Jamaican communities. Transcultural Psychiatry, 47(2), 252-275. DOI:

- Audu, I. A., Idris, S. H., Olisah, V. O., & Sheikh, T. L. (2011). Stigmatisation of people with mental illness among inhabitants of a rural community in northern Nigeria. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 59(1), 55-60. DOI:

- Barke, A., Nyarko, S., & Klecha, D. (2011). The stigma of mental illness in Southern Ghana: Attitudes of the urban population and patients’ view. Social Psychiatry of Psychiatric Epidemiology, 46(11), 1191-1202. https://dx.doi.org/

- Corrigan, P. W., & Shapiro, J. R. (2010). Measuring the impact of programs that challenge the public stigma of mental illness. Clinical Psychology Review. 30(8), 907-922. DOI: 10.1016/j.cpr. 2010.06.004

- Corringan, P. W., & Watson, A. C. (2007). How children stigmatize people with mental illness. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 53(6), 526-546. DOI:

- Fitzgerald, D., Rose, N., & Singh, I. (2016). Revitalizing sociology: Urban life and mental illness between history and the present. The British Journal of Sociology, 67(1), 138-160. DOI:

- Hinshaw, S. P. (2007). The mark of shame: Stigma of mental illness and agenda for change. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Kayama, M., Haight, W., Ku, M. L. M., Cho, M., & Lee, H .Y. (2017). East Asian and Us educators’ reflection on how stigmatisation affects their relationships with parents whose children have disabilities: Challenges and solutions. Children and Youth Services Review, 73, 128-144. DOI:

- Khan, N., Kausar, R., Khalid, A., & Farooq, A. (2015). Gender differences among discrimination & stigma experienced by depressive patients in Pakistan. Pakistan Journal of Medical Sciences, 31(6), 1432-1436. https://dx.doi.org/

- Kidane, E. G. (2014). Determinants of self and public stigma and discrimination against people with mental illness and their family in Jimma zone, Southwest Ethiopia (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). Ludwig-Maximilians-Universitat.

- Kok, J. K., & Low, S. K. (2017). Proposing a collaborative approach for school counseling. International Journal of school and Educational Psychology, 5(4), 281-289.

- Lakshiny (2015). Mental Disorder Is Going To Affect Over 3 Million Malaysians By 2020 – Will You Be One Of Them? Malaysian Digest.com. Retrieved from http://malaysiandigest.com/news/582570-mental-disorder-is-going-to-affect-over-3-million-malaysians-by-2020-will-you-be-one-of-them.html

- Lauber, C., Nordt, C., Falcato, L., & Rossler, W. (2004). Factors influencing social distance toward people with mental illness. Community Mental Health Journal, 40(3), 265-274. DOI:

- Link, B. G., Yang, L. H., Phelan, J. C., & Collins, P. Y. (2004). Measuring mental illness stigma. Schizophrenia bulletin, 30(3), 511-541.

- Lowder, D. M. (2007). Examining the stigma of mental illness across the lifespan (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). University of North Carolina, Wilmington.

- Ng, P., & Chan, K. F. (2000). Sex differences in opinion towards mental illness of secondary school students in Hong Kong. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 46(2), 79-88. DOI:

- Pallant, J. (2013). SPSS Survival manual: A step by step guide to data analysis using IBM SPSS (5th Ed). Crows Nest, NSW: Allen & Unwin.

- Reavely, N. J., & Jorm, A. F. (2011). Young people stigmatizing attitudes towards people with mental disorders. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 45(12), 1033-1039. DOI:

- Reichert, C. (2012). Mental illness stigma: An examination of the effects of label and gender on college students perceptions of depression and alcohol abuse (Unpublished master dissertation). Seton Hall University, New Jersey.

- Robles-Garcia, R., Fresan, A., Berlanga, C., & Martinez, A. (2013). Mental illness recognition and beliefs about adequate treatment of a patient with schizophrenia: Association with gender and perception of aggressiveness-dangerousness in a community sample of Mexico City. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 59(8), 811-818. DOI:

- Ronzoni, P., Dogra, N., Omigbodun, O., Bella, T., & Atitola, O. (2010). Stigmatization of mental illness among Nigerian schoolchildren. Journal of Social Psychiatry, 56(5), 507-514. DOI:

- Savrun, B. M., Arikan, K., Uysal, O., Cetin, G., Poyraz, B. C., Aksoy, C., & Bayar, M. R. (2007). Gender effect on attitudes towards the mentally ill: A survey of Yurkish university students. The Israel Journal of Psychiatry and Related Sciences, 44(1), 57-61.

- Sevigny, R., Yang, W., Zhang, P., Marleau, J. D., Yang, Z., Su, L., & Wang, H. (1999). Attitudes toward the mentally ill in a sample of professionals working in a psychiatric hospital in Beijing (China). The International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 45(1), 41-55. https://dx.doi.org/

- Shimmin, C. (2009). Understanding stigma through a gender lens. Canadian Women’s Health Network, 11(2). Retrieved from http://www.cwhn.ca/en/node/41610

- Song, L. Y., Chang, L. Y., Shih, C. Y., & Yang, M. J. (2005). Community attitudes towards the mentally ill: The results of a national survey of the Taiwanese population. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 51(2), 162-176. https://dx.doi.org/

- Stuart, H., & Arboleda-Flórez, J. (2012). A public health perspective on the stigmatization of mental illnesses. Public Health Reviews, 34(2), 1-18.

- Swami, V. (2012). Mental health literacy of depression: Gender differences and attitudinal antecedents in a representative British sample. Plos ONE, 7(11), 1-6. DOI:

- Taylor, S. M., & Dear, M. J. (1981). Scaling community attitudes toward the mentally ill. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 7(2), 225-240. DOI:

- The Star (1 July 2016). More Malaysians expected to suffer from mental illness by 2020. Retrieved from http://www.thestar.com.my/news/nation/2016/07/01/more-malaysians-expected-to-suffer-from-mental-illness-by-2020/mental-illness-by-2020/

- Ukpong, D. I., & Abasiubong, F. (2010). Stigmatizing attitudes towards the mentally ill: A survey in a Nigerian University Teaching Hospital. South African Journal of psychiatry 1(2), 56-59.

- Ward, E. C., Wiltshire, J. C., Detry, M. A., & Brown, R. L. (2013). African American men and women’s attitude towards mental illness, perception of stigma and preferred coping behaviors. Nursing Research, 62(3), 185-194. DOI:

- Williams, B., & Pow, J. (2007). Gender differences and mental health: An exploratory study of knowledge and attitudes to mental health among Scottish teenagers. Child & Adolescent Mental Health, 12(1), 8-12. DOI:

- Wirth, J. H., & Bodenhausen, G. V. (2009). The role of gender in mental-illness stigma: A national experiment. Psychological Sciences, 20(2), 169-173. DOI: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2009.02282.x

- Wolff, G., Pathare, S., Craig, T., & Leff, J. (1996). Community knowledge of mental illness and reaction to mentally ill people. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 2(168), 191-198. DOI:

- World Health Report. (2001). The world health report -Mental health: New understanding, new hope. Retrieved from http://www.who.int/whr/2001/en/

- Yeo, T. E. D., & Chu, T. H. (2017). Social-cultural factors of HIV-related stigma among the Chinese general population in Hong Kong. AIDS Care, 29(10), 1255-1259. DOI:

- Zubaidah, S., & Norfazilah, A. (2014). Attitude towards the mentally ill patients among a community in Tampoi, Johor, Malaysia 2012 to 2013. Malaysia Journal of Public Health Medicine, 14(3), 1-7.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

23 September 2019

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-067-9

Publisher

Future Academy

Volume

68

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-806

Subjects

Sociolinguistics, linguistics, literary theory, political science, political theory

Cite this article as:

Kim*, L. S., Nainee, S., Viapude, G. N., & Aun, T. S. (2019). Interactional Effect Of Educational Level And Gender On Public Stigmatization. In N. S. Mat Akhir, J. Sulong, M. A. Wan Harun, S. Muhammad, A. L. Wei Lin, N. F. Low Abdullah, & M. Pourya Asl (Eds.), Role(s) and Relevance of Humanities for Sustainable Development, vol 68. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 15-24). Future Academy. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2019.09.2