Abstract

Sustainability reporting was made mandatory to all public listed companies effective 2016 in Malaysia. Considering that not much has yet been discussed on the influence of organizational resources on the quality of reporting, particularly in the abovementioned setting, the proposed study seeks to understand the consequences of the recently introduced legal requirement. Accordingly, the main objective of this study is to investigate companies’ sustainability reporting behaviour via several aspects i.e. compliance and impression management tactics. A combination of institutional theory and resource-based theory is used to develop the research framework which proposes on the link between organizational factors such as sustainability committee, sustainability agenda, financial resources and environmental management system with the quality of sustainability report. Data will be collected from annual reports and analysed via structural equation modelling. The results are expected to give some insights to policy makers in Malaysia on the effectiveness of the newly introduced regulation, as well as providing some understanding on the needed directions which would expound better accountability and transparency.

Keywords: Mandatory sustainability reportinginstitutional theoryresource-based theory impression managementMalaysia

Introduction

In 2007, Bursa Malaysia has made an amendment where a new provision 29 is added to the listing requirement. It is the first time Bursa Malaysia has required listed companies to produce a statement related to corporate social responsibility activities. Following the enforcement in 2007, Bursa Malaysia has made another major step in promoting the sustainability practice among the listed companies in 2015. Bursa Malaysia takes the lead in ASEAN by introducing a globally benchmarked Environment, Social & Governance Index (ESG Index), and the FTSE4Good Bursa Malaysia ESG Index (F4GBM index) in December 2014.

Sustainability statement is now mandatory in the annual report of all listed companies in Malaysia. The amendment in Practice Note 9 in the Listing Requirements clearly spells out that annual report produced must contain a narrative sustainability statement which must include economic, social and economic risks and opportunities. Sustainability Reporting Guide (SRG) has then been issued for detailed reference. It is in line with the principle laid out by Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) in 1997 i.e. to include economic, environmental and social performance (Ioannou & Serafeim, 2016) and what defined by FTSE4Good Index, i.e. to demonstrate environment, social and governance practices. Under the amendment, the sustainability statement must not be incorporated in the chairman’s statement, but should be produced separately by the board of directors in the annual report. The sustainability information stated should be material, balanced, comparable and meaningful as stipulated in the SRG.

Problem Statement

A lot of studies have been done and found that even with detailed guideline, different countries may still have different style of integrated reporting, different motive in preparing and different information disclosed (Steyn, 2014). This is due to the “comply or explain” approach which gives room to the companies to be flexible in reporting (Jensen & Berg, 2012). Applying the case to Malaysia, though same regulations have been applied throughout the diverse range of companies, the sustainability reporting and strategy is much influenced by the personal perspective and integrity of the management team (Adams & McNicholas, 2007). Hence, it is essential for the authority i.e. Bursa Malaysia to understand the factors which are causing the difference in quality and extend of sustainability reporting after regulation takes place. Piecyk & Björklund (2015) has raised questions on the reason for low percentage disclosure in sustainability reporting, unsure whether it is due to lack of tools and resources or limited expertise and information technology application to manage the reporting.

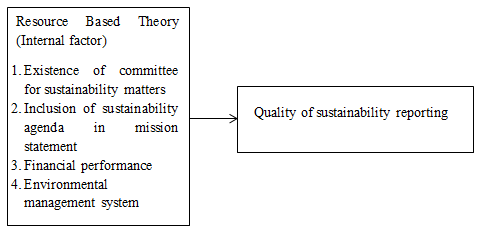

There are four commonly known resources which have direct and positive impact on the quality and extend of sustainability reporting. This includes board of directors (Nazari, Herremans, & Warsame, 2015; Amran, Ooi, Wong, & Hashim, 2016), mission and vision statement (Bartkus & Glassman, 2008; Amran, & Ooi, 2014), financial resources (Cormier & Magnan, 2003; Sulaiman, Abdullah, & Fatima, 2014) and existence of environmental management system (Jose & Lee, 2007; Nazari et al, 2015). By identifying the important internal factors that may potentially affect the quality of reporting, some suggestions may be provided to authorities and firms on what aspects need to be improved especially in strengthening firms internal resources. In short, the study would therefore look at the current reporting outcome after it is made mandatory to find evidence of compliance and impression management tactics, as well as the internal resource factors which may result in different extend of reporting and information revealed in the reports. This will provide an empirical result which will serve as a reference to the authority on what should be done after the implementation of regulation in order to improve further and to react to any limitation found in the existing requirement.

Research Questions

Based on the problem mentioned above, the research questions are as per below;

Has sustainability reporting produced by companies in Malaysia complied with the mandatory requirements as set out by Bursa Malaysia? Are impression management tactics being employed in their sustainability reporting?

Do internal factors influence the quality of mandatory sustainability reporting in Malaysia?

Purpose of the Study

The main aim of the study is to investigate the sustainability reporting behaviour after it is made mandatory and the internal reason of such behaviour. The following objectives are developed in conjunction with the research questions.

To examine the compliance level and impression management tactics employed by companies in Malaysia after mandatory sustainability reporting was introduced.

To examine various internal factors and their relationships with the quality of sustainability reporting.

Literature Review and Framework

The institutional theory and resource based theory is used to understand the relationship between the resources of the firm and the quality of sustainability reporting. Under the research by Bansal (2005), resource based theory has been assessed together with institutional factors in shaping the sustainability development of a firm. The result of his research has shown that institutional factors such as penalties and media attention are more influential at the beginning of sustainability development but it is the resource-based variables such as international experience that brings further development in the long term.

Institutional Theory– Coercive Isomorphism

Institutional theory posits that organisations tend to change due to the need of legitimacy rather than for rival pressure or efficiency (DiMaggio & Powell, 1983). Therefore, both legitimacy theory and institutional theory can provide “carrot and stick” approach whereby legitimacy serves as a “carrot” where it is an objective of a firm to be legitimate in a society by having sustainability reporting while the regulation imposed by Bursa Malaysia has become the “stick” to motivate companies to go after the “carrot” (Fatima, Abdullah, & Sulaiman, 2015). This has made firms become homogenous and much similar without making them more efficient, which resulted in isomorphism (Liang, Saraf, Hu, & Xue, 2007).

Coercive isomorphism is the "the formal and external pressures exerted upon them by other organizations upon which they are dependent, and the cultural expectations in the society within which the organizations function" (DiMaggio & Powell, 1983). This pressure may stem from the government and industry regulations, standards, policies and professions (Liang, Saraf, Hu, & Xue, 2007). In the research conducted after the implementation of mandatory CSR disclosure in Malaysia, it has been found that there is a strong positive relationship between regulation and the extend of CSR reporting which has supported coercive isomorphism (Othman, Darus, & Arshad, 2011). It has also been supported by other researches in other countries that regulations do have a major influence in disclosure quality Rahaman, Lawrence, & Roper 2004; Clemens & Douglas, 2006). In this study, coercive isomorphism is used to test the impact of the regulation on sustainability reporting.

Resource based theory

Barney (1991) has set a good introduction to resource-based theory as he defined the resource-based view of the firm which describes conditions under which unique or distinctive resources possessed by a firm are a source of sustained competitive advantage (Barney, 1991). The resources can be tangible or intangible assets that a firmmcontrols and uses to conceive or implement strategies (Barney & Hesterly, 2006). In other words, resources are those distinctive assets which can be used by a firm in implementing strategies to attain competitive advantage. Russo and Fouts (1997) concluded that green image and environmental friendly companies may increase their sales through environmental sensitive customers resulting in them to have more resources for better environmental disclosure (Sulaiman et al, 2014).

Quality of Sustainability Reporting- Compliance and Impression Management Tactics

Before evaluating on the quality of sustainability reporting, it is better to understand the qualities perceived by the general guideline, i.e. GRI guideline so as to have a yardstick to study the change in quality of reporting later in the research. The GRI guidelines offer core content for reporting that is relevant to all organizations. Its indicator protocols advise on definition, scope, and compilation methods to help organizations to ensure a meaningful and comparable reporting. Among the evaluation criteria suggested are on completeness, materiality and responsiveness.

According to Merkl-Davies & Brennan (2007), corporate reporting can be driven by either conveying information for the users’s decision making or as organizational impression management and opportunistic behavior designed to enhance the company’s image. Sustainability reporting regulation is rather flexible without specific format to comply and firms are given a certain flexibility to decide on what to report (Sandberg & Holmlund, 2015). It has been found that most firms tend to deflecting, obfuscating, or rationalizing their poor sustainability performance through impression management in disclosing the information (Cho et al, 2010) where companies try to create favourable image about their operation and may not disclose true information (Onkila, 2009; Coupland, 2006). Few researches have categorized the tactics however it is not standardised (Sandberg & Holmlund, 2015). For example, Hooghiemstra (2000) has categorised the tactics into “Acclaiming” i.e. presenting favourable event by maximising positive impacts and “Accounting” i.e. presenting unfavourable event by minimising the negative impacts. Another research has used classic rhetorical strategies of ethos (credibility), logos (reason) and pathos (emotion) to classify the impression management tactics (Higgins & Walker, 2012).

Research Framework

The research framework is presented in Figure

In order to focus on the sustainability agenda, it has been found that the existence of committee specialized in sustainability agenda and preparing sustainability reporting has positive relationship with the quality of sustainability reporting (Clarkson et al, 2008). This has been further extended by Nazari et al (2015) in Canada, concluding existence of special committee in establishing strategic control for sustainability will improve the quality of sustainability reporting.

Mission statement is a tool which management can communicate its beliefs, perspectives, and approaches to employees and other stakeholders (Hirota, Kubo, Miyajima, Hong, & Park, 2010). Mission statement is very important for firms because it “can help focus the organization on what really matters – to itself as well as to its stakeholders” (Ireland & Hirc, 1992). Firms which seek for environmental friendly reputation would need to have an environmental friendly policy given that corporate mission statement is the main driver for inspiring green strategies formulation which will then drive the firm towards their plan (Abdelzaher & Newburry, 2016). As strategy will affect the action of organisations, the action will then create sustainable value, contributing to sustainable development (Hart & Milstein, 2003). This is further proven by Bartkus & Glassman, (2008) stating that firms that incorporate environmental concern in their mission statements are more likely to enforce their voiced commitment. Besides, Amran et al (2014) has also concluded that by embedding CSR values in mission and vision may increase the sustainability reporting quality.

Another vital resource of a company would be financial resource. However, financial factor in previous studies has shown inconsistency in the result. One of the controversial findings are leverage does not have positive relationship with reporting quality (Cormier & Magnan, 2003; Sulaiman et. al. 2014). However, this result is opposed by Ahmad, Salleh, and Junaini (2003). Financial perspective can be viewed from two angles i.e. profitability and liquidity (Kent & Monem, 2008). It is commonly known that companies with higher profitability are more likely to have more resources and produce better sustainability reporting (Haniffa & Cooke, 2005). Furthermore, leverage is another important financial aspect due to creditors as one of the most important stakeholders of a company (Chan & Kent, 2003). The commitment to debt may reduce the resources of a firm to fund a quality disclosure (Sotorrío & Sánchez, 2010).

The adoption of certified environmental management system (EMS) is claimed to ensure improvement in environmental and operational performance (Melnyk, Sroufe, & Calantone 2003). This result is supported by other researches which the environmental performance has improved after the adoption of ISO14001 (ISO14001 is one of the most popular and extensive EMS standards which is certified by International Organization for Standardization (Miles et al, 1997), describing “the part of the overall management system that includes organizational structure, planning activities, responsibilities, practices, procedures, processes and resources for developing, implementing, achieving, reviewing and maintaining the environmental policy” (ISO 14001)) (Anton, Deltas, & Khanna 2004; King, Lenox, & Terlaak, 2005; Henri & Journeault, 2010). However, the earlier studies are mostly focusing on the relationship between ISO14001 adoption and company’s performance but not in facilitating reporting (Nazari et al, 2015). According to Jose & Lee (2007), companies with voluntary sustainability disclosure are found to start adopting ISO14001. Nazari et al (2015) have also found that companies adopting ISO14001 will produce better sustainability reporting in Canada.

Research Methods

Data collection

In this study, companies listed on FTSE Bursa Malaysia 100 Index (FBM100) are selected as the sample with a total sample of 100 companies out of the universe of 805 companies which listed on the main markets in FTSE Bursa Malaysia EMAS Index. FBM100 comprises the constituents of FTSE Bursa Malaysia KLCI (30 largest companies by market capitalization) and the FTSE Bursa Malaysia Mid 70 Index (next 70 largest companies by market capitalization) (Lean & Tan, 2010). As confirmed by various researches from different countries that firm size and market capitalization has positive relationship with sustainability performance and quality of sustainability reporting (Li, Zhang, & Foo, 2013; Amran & Haniffa, 2011; Henri & Journeault, 2008). Besides, large companies tend to invite more attention from stakeholders and therefore are subject to higher possibility of impression management tactics employed in sustainability reporting (Sandberg & Holmlund, 2015). After the companies are chosen, timing is the next concern. As most of the companies are compulsory to produce sustainability statement for the financial year ended 2016 and 2017, annual reports and sustainability reporting from the year 2016 onwards are selected. However, depending on the financial year closing date and the reliability of data, reports of 2018 might be selected. For those companies which started to produce sustainability report in 2016, an average result shall be obtained between 2016 and 2017. On the other hand, one-year data shall be obtained for those which started in 2017 or 2018.

Variables and measurement

By referring to the hypotheses formed, the variables are identified below with the measurement of each variable that are used to test the hypotheses of this study.

Dependent variables

Measuring the dependent variable i.e. quality, requires content analysis of sustainability reporting. The content analysis is performed by using a checklist approach. The first approach will be applied to examine the compliance of sustainability reporting while the second approach is used to examine the existence of impression management tactics. Vormedal & Ruud (2009) has done a similar research in Norway on the compliance level of mandatory sustainability reporting by using a scoring system categorizing the compliance level into five categories, namely not mentioned, mentioned, insufficient, satisfactory and very satisfactory, scoring from zero to four. Similar scoring system shall be adapted and modified based on the mandatory disclosure items as mentioned above. Those companies which fall under the score of 3 and 4 are considered as complying toward the regulation. The scoring system is summarized as below Table

Furthermore, in order to become a quality reporting, one must also ensure that the information disclosed is balanced, comparable and meaningful. Balanced as defined in the guide by Bursa Malaysia (2015) as unbiased and contain both positive and negative issue. Therefore, one point will be given for any disclosure of negative aspects and zero for one sided disclosure. In order for information to be comparable and meaningful, the most objective measure would be quantitative data. This is also consistent with other researches whereby quantitative data of non-financial reporting indicates a better quality of the reporting (Sulaiman et al., 2014; Nazari et al., 2015). Therefore, those which include meaningful and comparable quantitative data will be rewarded one point and zero to those who do not.

On the other hand, to measure the impression management tactics used by the firm, the model suggested by Sandberg & Holmlund (2015) is adopted whereby the tactics are first categorised into presenting actions and writing styles. Presenting actions tactics are looking at the way the firm presents its sustainability performance and activities. Writing styles tactics will focus on how the sentences are structured using impression management tactics.

There are four tactics identified in presenting actions, of which “description” and “admission” are known to be neutral in nature while “praise” and “defense” are tactics used to magnify the goods and cleaning the bad actions. All four tactics identified in writing styles by Sandberg & Holmlund (2015) are known to be impression management tactics to window dress the sustainability statement. On the other hand, the writing tactics include subjective style, positive style, vague style and emotional style. Since all are non-neutral styles, a neutral style i.e. objective style is added to collect a more comprehensive data for analysis. For this study purpose, only writing style is used in the study to find evidence of impression management tactics. The definition of each tactics is adopted from Sandberg & Holmlund (2015) (Table

To measure the impression management, while performing content analysis in the sustainability statement, each sentence is codified with each tactic. The way of measurement is different from Falschlunger, Eisl, Losbichler, & Greil (2015) which look at graphical presentation while this study is analysing sentences. The frequency of each tactic is then summed up and divided into impression management category and neutral category. The percentage of impression management category over the total tactics will then decide on the impression management level in a sustainability statement.

Independent variables

In the research of Clarkson, Li, Richardson, & Vasvari (2008), the existence of environmental related issue committee in the board of directors are assessed as a dummy variable that will affect the performance of environmental performance. Similarly, this study will adopt this as the variable to test the management resource’s impact on the quality of sustainability reporting produced. Value of ‘1’ would be indicated for the existence of such committee while ‘0’ would be assigned to those absent.

The inclusion of sustainability agenda in the mission statement has been a factor to be considered for producing a better sustainability report as sustainability is better communicated to the employees and also the preparer of the report. The mission statement should include the relevant key words like sustainability, sustainable, green, environmental, eco, etc. Value of “1” would be given if the mission statement contains any of the relevant keywords while “0” for those which are not. Therefore, the measurement will be based on dichotomous value of “1” for those which produce sustainability reporting before 2016 and “0” for those which never produce before. This measurement has also been adopted in Abdelzaher & Newburry (2016).

The next factor to be examined would be the financial performance and it is generally divided into two, i.e. profitability and leverage or liquidity. The variables are normally measured by the financial ratios which data is available in the financial reports. In previous studies, the most common ratio to measure profitability would be Return on Assets (ROA) while leverage is measured by debt ratio (Brammer & Pavelin, 2006; Kent & Monem, 2008; Stanny & Ely, 2008). The measurement goes by taking net profit after tax divided by total assets. This will actually show how good does a management managing its asset resources to generate return for the company (Dess & Robinson, 1984). Debt ratio on the other hand, is looking at the ratio of total debt over total assets. This will actually provide a picture of capital structure of a firm and the gearing status to see if a firm has sufficient fund resources for compliance and improvement on sustainability issues.

About the relationship between the presence of environmental management system and the quality of sustainability reporting, dichotomous value of “1” and “0” is assigned to the companies complied with ISO14001 and those which are not respectively and this is consistent with Nazari et al (2015). ISO 14001 is an ISO Standards that have been developed to help companies to formulate an environmental management system in achieving the firm’s environmental goals. Therefore, the existence of such compliance may act as an important resource for the firm to have a better quality sustainability statement.

Control variables

The control variables in this study are firm size (market capitalization), the industry which the firm operates in (environmental sensitive industry and non-environmental sensitive industry), and previous experience (produce sustainability reporting before 2016 and vice versa).

Method of Data Analysis

In order to answer the research questions and to test the hypotheses, descriptive statistics and structural equation modelling will be employed.

Findings

As this is merely a conceptual paper before research is carried out, there will be no finding at the moment.

Conclusion

In short, this research tends to give an insight on what is happening after mandatory sustainability reporting. While looking at the impact of regulation on the reporting, other internal factors are also included to find out whether resources are essential for compliance. Without proper resource, the maintenance in terms the quality of compliance might be very challenging or even unachievable. By studying the disclosure pattern through impression management tactics, the study may also provide a picture of how firms’ attitude towards this regulation and whether sustainability development has improved since then.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to extend their appreciation to Universiti Sains Malaysia for the short-term grant entitled The Usage of Social and Environmental Information in Financial Decision Making (Grant No. 304/ PMGT/6313240), which made this study and paper possible.

References

- Abdelzaher, D., & Newburry, W. (2016). Do green policies build green reputations? Journal of Global Responsibility, 7(2), 226-246.

- Adams, C., & McNicholas, P. (2007). Making a difference: Sustainability reporting, accountability and organisational change. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 20(3), 382-402.

- Ahmad, Z., Salleh, H., & Junaini, M. (2003). Determinants of Environmental Reporting in Malaysia. International Journal of Business Studies, 11(1), 69-90.

- Amran, A., & Haniffa, R. (2011). Evidence in development of sustainability reporting: a case of a developing country. Business Strategy and the Environment, 20(3), 141-156.

- Amran, A., & Ooi, S. (2014). Sustainability reporting: meeting stakeholder demands. Strategic Direction, 30(7), 38-41.

- Amran, A., Ooi, S., Wong, C., & Hashim, F. (2016). Business Strategy for Climate Change: An ASEAN Perspective. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 23(4), 213–227.

- Anton, W., Deltas, G., & Khanna, M. (2004). Incentives for environmental self-regulation and implications for environmental performance. Journal of Environmental Economics and Management, 48(1), 632-654.

- Bansal, P. (2005). Evolving sustainably: A longitudinal study of corporate sustainable development. Strategic management journal, 26(3), 197-218.

- Barney, J. (1991). Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. Journal of management, 17(1), 99-120.

- Barney, J., & Hesterly, W. (2006). Organizational economics: Understanding the relationship between organizations and economic analysis. The SAGE handbook of organization studies, 111-148.

- Bartkus, B., & Glassman, M. (2008). “Do firms practice what they preach? The relationship between mission statements and stakeholder management. Journal of Business Ethics, 83(2), 207-216.

- Brammer, S., & Pavelin, S. (2006). Voluntary environmental disclosures by large UK companies. Journal of Business Finance & Accounting, 33(7-8), 1168-1188.

- Bursa Malaysia. (2015). Sustainability Reporting Guide. Kuala Lumpur: Bursa Malaysia Securities Berhad.

- Chan, C., & Kent, P. (2003). Application of stakeholder theory to the quantity and quality of Australian voluntary corporate environmental disclosures. Annual Conference of the Accounting and Finance Association of Australia and New Zealand.

- Cho, C., Roberts, R., & Patten, D. (2010). The language of U.S. corporate environmental disclosure. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 35(4), 431-443.

- Clarkson, P., Li, Y., Richardson, G., & Vasvari, F. (2008). Revisiting the relation between environmental performance and environmental disclosure: an empirical analysis. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 33(4/5), 303-327.

- Clemens, B., & Douglas, T. (2006). Does coercion drives firms to adopt ‘voluntary’ green initiatives? Relationships among coercion, superior firm resources, and green initiatives. Journal of Business Research, 59, 483-491.

- Cormier, D., & Magnan, M. (2003). Environmental Reporting Management: A Continental European Perspective. Journal of Accounting and Public Policy, 22, 43-62.

- Coupland, C. (2006). Corporate social and environmental responsibility in web-based reports: currency in the banking sector? Critical Perspectives on Accounting, 7(7), 865-881.

- Dess, G., & Robinson, R. (1984). Measuring organizational performance in the absence of objective measures: the case of the privately‐held firm and conglomerate business unit. Strategic management journal, 5(3), 265-273.

- DiMaggio, P., & Powell, W. (1983). The iron cage revisited: Institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields. American Sociological Review, Vol. 48 No. 2, 147-160.

- Falschlunger, L., Eisl, C., Losbichler, H., & Greil, A. (2015). Impression management in annual reports of the largest European companies: A longitudinal study on graphical representations. Journal of Applied Accounting Research, 16(3), 383-399.

- Fatima, A., Abdullah, N., & Sulaiman, M. (2015). Environmental disclosure quality: examining the impact of the stock exchange of Malaysia’s listing requirements. Social Responsibility Journal, 11(4), 904-922.

- Haniffa, R., & Cooke, T. (2005). The impact of culture and governance on corporate social reporting. Journal of accounting and public policy, 24(5), 391-430.

- Hart, S., & Milstein, M. (2003). Creating sustainable value. Academy of Management Executive, 17(2), 56-67.

- Henri, J. F., & Journeault, M. (2008). Environmental performance indicators: An empirical study of Canadian manufacturing firms. Journal of environmental management, 87(1), 165-176.

- Henri, J. F., & Journeault, M. (2010). Eco-control: the influence of management control systems on environmental and economic performance. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 35(1), 63-80.

- Higgins, C., & Walker, R. (2012). Ethos, logos, pathos: strategies of persuasion in social/environmental reports. Accounting Forum, 36(3), 194-208.

- Hirota, S., Kubo, K., Miyajima, H., Hong, P., & Park, Y. (2010). Corporate mission, corporate policies and business outcomes: evidence from Japan. Management Decision, 48(7), 1134-1153.

- Hooghiemstra, R. (2000). Corporate communication and impression management – New perspectives why companies engage in social reporting. Journal of Business Ethics, 27, 55-68.

- Ioannou, I., & Serafeim, G. (2016). The consequences of mandatory corporate sustainability reporting: evidence from four countries. Harvard Business School Research Working Paper No. 11-100.

- Ireland, R., & Hirc, M. (1992). Mission statements: importance, challenge, and recommendations for development. Business Horizons, 35(3), 34-42.

- Jensen, J., & Berg, N. (2012). Determinants of traditional sustainability reporting versus integrated reporting. An institutionalist approach. Business Strategy and the Environment, 21(5), 299-316.

- Jose, A., & Lee, S. (2007). Environmental reporting of global corporations: a content analysis based on website disclosures. Journal of Business Ethics, 72(4), 307-321.

- Kent, P., & Monem, R. (2008). What drives TBL reporting: good governance or threat to legitimacy? Australian Accounting Review, 18(4), 297-309.

- King, A., Lenox, M., & Terlaak, A. (2005). The strategic use of decentralized institutions: exploring certification with the ISO 14001 management standard. The Academy of Management Journal, 48(6), 1091-1106.

- Lean, H., & Tan, V. (2010). Existence of the day-of-the-week effect in FTSE Bursa Malaysia. UKM Journal of Management, 31, 3-11.

- Li, Y., Zhang, J., & Foo, C.-T. (2013). Towards a theory of social responsibility reporting: Empirical analysis of 613 CSR reports by listed corporations in China. Chinese Management Studies, 7(4), 519-534.

- Liang, H., Saraf, N., Hu, Q., & Xue, Y. (2007). Assimilation of enterprise systems: the effect of institutional pressures and the mediating role of top management. MIS quarterly, 59-87.

- Melnyk, S., Sroufe, R., & Calantone, R. (2003). Assessing the impact of environmental management systems on corporate and environmental performance. Journal of Operations Management, 21(3), 329-351.

- Merkl-Davies, D., & Brennan, N. (2007). Discretionary disclosure strategies in corporate narratives :. Journal of Accounting Literature, 26, 116-196.

- Nazari, J., Herremans, I., & Warsame, H. (2015). Sustainability reporting: external motivators and internal facilitators. Corporate Governance, 15(3), 375-390.

- Onkila, T. (2009). Corporate argumentation for acceptability: reflections of environmental values and stakeholder relations in corporate environmental statements. Journal of Business Ethics, 87(2), 285-298.

- Othman, S., Darus, F., & Arshad, R. (2011). The influence of coercive isomorphism on corporate social responsibility reporting and reputation. Social Responsibility Journal, 7(1), 119-135.

- Piecyk, M., & Björklund, M. (2015). Logistics service providers and corporate social responsibility: sustainability reporting in the logistics industry. International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management, 45(5), 459-485.

- Rahaman, A., Lawrence, S., & Roper, J. (2004). Social and environmental reporting at the VRA: institutionalised legitimacy or legitimation crisis? Critical Perspectives on Accounting, 15, 35-56.

- Russo, M., & Fouts, P. (1997). A resource-based perspective on corporate environmental performance and profitability. Academy of management Journal, 40(3), 534-559.

- Sandberg, M., & Holmlund, M. (2015). Impression management tactics in sustainability reporting. Social Responsibility Journal, 11(4), 677-689.

- Sotorrío, L., & Sánchez, J. (2010). Corporate social reporting for different audiences: the case of multinational corporations in Spain. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 17(5), 272-283.

- Stanny, E., & Ely, K. (2008). Corporate environmental disclosures about the effects of climate change. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 15(6), 338-348.

- Steyn, M. (2014). Organisational benefits and implementation challenges of mandatory integrated. Sustainability Accounting, 5(4), 476-503.

- Sulaiman, M., Abdullah, N., & Fatima, A. (2014). Determinants of environmental reporting quality in Malaysia. International Journal of Economics, Management and Accounting, 22(1), 63-90.

- Vormedal, I., & Ruud, A. (2009). Sustainability reporting in Norway–an assessment of performance in the context of legal demands and socio‐political drivers. Business Strategy and the Environment, 18(4), 207-222.

- .

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

02 August 2019

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-064-8

Publisher

Future Academy

Volume

65

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-749

Subjects

Business, innovation, sustainability, environment, green business, environmental issues

Cite this article as:

Wong, C. C., Jalaludin, D., & Phua, L. K. (2019). Mandatory Sustainability Reporting in Malaysia: Impact and Internal Factors. In C. Tze Haw, C. Richardson, & F. Johara (Eds.), Business Sustainability and Innovation, vol 65. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 469-480). Future Academy. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2019.08.47