Abstract

Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) could today be considered the world’s most popular sustainability information disclosure standards. Yet it is seen by many as a symbolic gesture to pacify the existing masses than an instrument of sustainability disclosure. It is therefore the aim of this study to examine the effectiveness of the application of GRI by organizations in Africa’s two biggest economies in relation to the global application. The paper is purely conceptual basing its analysis on past literatures. In the main, an attempt was made to review literatures from other countries though priority was given to Africa’s two largest and most developed economies (Nigeria and South Africa). The major discovery was that GRI application to some extent proves more successful in South Africa than is some developed economies. However, challenges like Africa’s unique business environment for the effective and efficient implementation of GRI standard and guidelines still remains in the continent.

Keywords: GRI (Global Reporting Initiative)sustainability disclosurestandard disclosuresgeneral standard disclosurespecific standard disclosure

Introduction

Since its introduction in 1997, the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) has been incorporated by several organizations in both the private and public sectors (Brown, de Jong, & Levy, 2009; Fonseca, 2010). For this motive, it is regarded as the most widely satisfactory nonfinancial or sustainability reporting guideline at present. Notwithstanding this general response, it is seen by many scholars as an emblematic gesture to pacify the anxiety of the masses than an effective sustainability material disclosure tool (Fonseca, 2010). Records show that between 1999 and 2010 a total of 5,902 companies worldwide have registered with GRI (Marimon, del Mar Alonso-Almeida, del Pilar Rodriguez, & Alejandro, 2012). On average about 492 companies has been registering with GRI annually. Since its introduction the standard has seen the release of several updated or upgraded versions from GRI-1 (G1), GRI-2 (G2), GRI-3 (G3) to GRI-4 (G4) which is the latest version introduced in 2013.

Being a new development, this study is purely theoretical with the researcher counting on past studies to make an unbiased valuation of the adoption and application of GRI by both the private and public sectors in Africa.

Problem Statement

In terms of application, GRI has found some success in its major objective of the influences of environmental and social nonfinancial information (Dingwerth & Eichinger, 2010). However, huge challenges still remain as far as GRI standards and guidelines are concern with regards to sustainability reporting. Most of the achievements of GRI reporting are documented by organizations functioning in developed economies. There have been successes in the usefulness and quality of Triple Bottom Line (TBL) reporting (Wills, 2003), company reflectiveness (Marimon, del Mar Alonso-Almeida, del Pilar Rodríguez, & Alejandro, 2012), output efficiency (Barkemeyer, Preuss, & Lee, 2015), and many more areas. In Africa, GRI application according to Dawkins and Ngunjiri (2008) showed that revelation by local firms in South Africa of nonfinancial information were “significantly higher than that of the Fortune Global 100”. Though this sounds optimistic, nonfinancial reporting through GRI in Africa faces encounters like developing GRI for public sector supplement, strict observance to guidelines, untested guidelines, and lack of requirements in the guidelines for factors uncharacteristic and unique to African organizations (Antoni & Hurt, 2006). There are therefore, great challenges in these areas of GRI acceptance and implementation by organizations and institutions in Africa.

Research Questions

Attempt will be made in this literature to answer the following questions:

Are the current GRI guidelines fit for the public sector in Africa?

Are organizations in Africa adhering strictly to the GRI guidelines?

Does GRI takes into consideration Africa’s unique and peculiar characteristics?

Purpose of the Study

In this study; the researcher scrutinises the effectiveness of the application of GRI by African organizations in relation to global usage. This write-up laid weight and focused more on Africa’s two principal economies of Nigeria and South Africa.

Research Methods

As already mentioned earlier, this paper is a theoretical study related to the accomplishments and challenges of GRI’s adoption in Africa. The targeted zones to be covered is Africa are Nigeria and South Africa’s economies. However, most of the review was done on international bases. The bulk of the work was based on the evaluation of literature that covers the roles, achievements and challenges of GRI. Precisely, the approaches used in this scholarship was based on qualitative, inductive, iterative and representative descriptive perceptive (Fonseca, 2010). This method is mainly beneficial in the nonexistence of basically tested models or simulations to elucidate a precise communal spectacle (Fonseca, 2010).

Findings

6.1. Historical Development of GRI

Perhaps the first person to have instinctively triggered sustainability reporting was Racheal Carson when in 1962 she highlighted questions about industrialization’s impact on natural resources, human health and the environment (Malarvizhi & Yadav, 2009). Little did anyone comprehend then that it will transformed sustainability information disclosure as being experienced today. According to Bell and Lundblad (2011), nonfinancial reporting has been around since the 1970s. In 1972, the Stockholm UN conference on environmental issues leads to the formation of the World Commission on Environment and Development (WCED); which marks a histrionic twist in environmental reporting. One of the reports issued by WCED in 1987 was an advancement as the term “sustainable development” was created and demarcated. The report defines sustainable development as “development that meets the needs of the present generation without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their needs”.

The Stockholm conference was followed by the 1992 Earth Summit conference in Rio de Janerio titled Earth & Development (Bartelmus, 2008). This meeting was then followed by the Johannesburg Summit in 2002. The Johannesburg Summit reiterate what later became known as the TBL or mega reporting by companies, to cover the characteristics of economic, environmental and social aspects. Earlier in 1987, the Kyoto Protocol which empowered manufacturing countries to mutually reduced greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions by 5.2% before the year 2012 was signed (Carbonify.com, 2014). By 2015 the Paris Climate Summit which was held in France, agreed on a statement in which developed countries assured to cut-down on GHG emissions and support poorer nations financially to fight the effects of climate change and global warming.

The most widespread and popular voluntary disclosure guidelines and standards are those issued by the GRI. Formed in 1997 the GRI began with an uncertain take off in 1999 (Brown, De Jong, & Lessidrenska, 2009; Lamprinidi & Kubo, 2013). The organization itself is autonomous nongovernmental organization (NGO) formed with headquarters in Amsterdam, Holland (Dingwerth & Eichinger, 2010). GRI is aimed at refining employer/employee relationship and employer/stakeholder relationship. Its main objective is to advance and inspire an all-inclusive structure for sustainability information disclosure. Among the advantages of GRI according to Lamprinidi and Kubo (2013) are better-quality transparency and accountability, as well as the fact that it cuts high demand for information outside economic operations from businesses

6.2. The Reporting Principles of GRI Framework

There are around ten principles of GRI which defined the code of conduct of sustainability reporting through GRI framework. These principles are deliberated below (Initiative, 2013):

Materiality: - GRI report should encompass information on topics and indicators that points out corporate economic, environmental and social impacts. This information should be weighty enough to stimulate the evaluation and desires of stakeholders.

Stakeholders Inclusiveness: - this principle identifies that stakeholders be involved in the reporting by consulting them and classifying their expectations and interests. The sustainability report should explain how the organization has accomplished the individual concerns of stakeholders.

Sustainability Context: - this principle seeks to have the environmental report presented in a method looking at what has been exploited today and showing what the organization anticipates to do in the future to the perfection or deterioration of economic, environmental, social conditions and development trends at local, regional and global levels.

Completeness: - demands that sustainability reports grounded on the GRI framework must comprise information on material topics and indicators. The report’s latitude must be clearly defined to show significant economic, environmental and social impacts. This is necessary to permit stakeholders to assess the reporting entity’s presentation for the period.

Balanced: - apart from completeness a GRI report must be impartial, objective and well balance to reflect good and bad as well as positive and negative; aspects of the organization’s performance.

Comparability: - an environmental report must be analogous to other environmental reports elsewhere. To ensure this the “Comparable” principle states that issues and trials should be selected, compiled and reported reliably. Reported information in GRI reports should make it possible for users to be able to analyse changes in the organization’s performance overtime, and should support analysis relative to other organizations, industries, sectors, economies, etc.

Accuracy: - comparability is better heightened by the “accuracy” principle which emphasizes that qualitative and quantitative measurements should be adequately accurate and detailed for concerned parties to assess the organizations performance.

Timeliness: - GRI sustainability reports should also be “Timely”. Timeliness is required so that users could make knowledgeable decisions. Reporting is done at interims or on regular bases. The practicality of any information lies in the fact that it is disclosed in time for users to successfully integrate it into their decision-making process. In addition to this, information reported should be “Clear”.

Clarity: - clarity principle entails comprehension, understanding and accessibility of information for users. Whatever method of broadcasting applied the information in the report must be simplified enough for stakeholders to digest. Information in the form of pictorial, graphical and diagrams helps a lot in this respect.

Reliability: - finally, GRI report frameworks are oversee by the “Reliability” principle. To ensure reliability the information and processes used to prepare the report should be valid and qualitative. The method of gathering, recording, compiling, analysing and disclosing information should be such that could be subject to examination. Any examination of the statement must recognize the quality and materiality of information contain therein.

6.3. The Contents of Standard Disclosure of G4

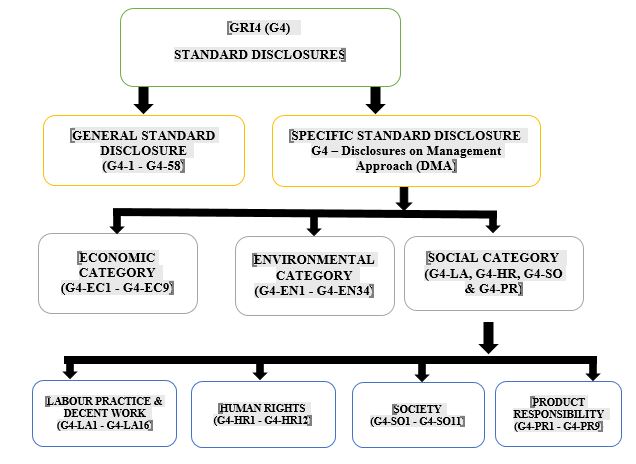

G4 provides for two types of disclosures under Standard Disclosure (Initiative, 2013). These comprise:

General Standard Disclosure (GSD)

Specific Standard Disclosure (SSD)

6.3.1. General Standard Disclosure

The GSD is on the broad aspects of an organization’ characteristics and comes under Paragraph 237. Its requirements touch on the following aspects of an organization (Table

The SSD on the other hand deals with the three aspects of triple bottom line (TBL) reporting. They are:

The Economic Category

The Environmental Category

The Social Category

It should be emphasized that aspects to be disclosed under each of these categories are aspects that are “material” to the organization’s or companies’ operations (Table

6.3.2. Economic Sustainability Disclosure (G4-EC1 to G4-EC9)

6.3.3. Environmental Sustainability Disclosure (G4-EN1 to G4-EN34)

6.3.4. Social Sustainability Disclosure

Sub-categoryG4 Sustainability Code

Labour Practices & Decent Work G4-LA1 - G4-LA16

Human Rights G4-HR1 - G4-HR12

Society G4-SO1 - G4-SO11

Product Responsibility G4-PR1 - G4-PR9

6.4. Review of Empirical Studies

Studies on sustainability disclosure have explored many areas. Literature on emerging and developing economies especially in Africa are scanty as most of the work completed in this field are in relation to the economies of developed nations. Fonseca (2010) sees GRI is the global

The work of Adams and Petrella (2010) was based on the UN Global Compact Leaders’ Summit which discusses the possibilities for the connection and cooperation that will lead to change. It was revealed that there was a general acceptance by business organizations to be more socially and environmentally accountable, but they lack the technical know-how and management’s capacity to make this possible. This was mainly attributed to shortage of sustainability mangers produced by universities. The study did not observe the application of disclosure standards but the availability of work force to administer sustainability standards.

In another study Wills (2003), stated that GRI sustainability guidelines of 2000 advances the worthiness and quality of economic, environmental and social impact and performance. The study which was grounded on non-African Stock Exchanges like the Dow Jones Sustainability Group Index, the JANTZI Social Index, the INNOVEST EcoValue’zi, SRI community, etc.; stresses that broad diversity of disclosure needs and wide range of user’s expectation are GRI’s major challenges. The study did not deliberate on other challenges like diversity in culture, economic environment and level of advancement unique to African or developing economies.

Brown, de Jong, and Levy (2009) observed that GRI is the best-known sustainability framework for voluntary reporting of environmental and social performance by bigger organizations. Since its diffident take off in 1999, GRI has by far been the most effective reporting tool. However, it cannot serve as a rallying agent for many societal actors. The framework focusses more on large global companies and financial institutions together with international business management consultancies, thereby disregarding less active civil society organizations and organized labour. This could be mainly due to incorporating GRI into existing organizational structures, the multi-stakeholder procedure and the underdevelopment base of users. They further observed that GRI introduced three institutional innovations viz: multi-stakeholder process, institutionalization and creating an organization and mostly successful under conditions of limited resources, visibility and political power. Moreover, it serves as a win-win solution and efficient gain for all actors (Brown, De Jong, & Lessidrenska, 2009).

Levy, Brown and de Jong (2010) stated that GRI has fallen short of its aspirations to use disclosure to empower nongovernmental organizations. They made three important observations with regards to GRI implementation:

Institutional theory needs to focus more on economic structures, strategies and resources.

Entrepreneurship by NGO’s is constrained by the power of bigger institutions and by the compromises required to initiate change.

NGOs strategies is a representation capable of shifting or transforming corporate governance.

Isaksson and Steimle (2009) targeted cement manufacturers as their study queries the contribution of sustainability development and recommends criteria for assessing corporate sustainability grounded on GRI to know whether GRI contains the indicators for determining corporate sustainability. It resolved that GRI guidelines are not sufficient to make sustainability reporting in cement industry significant and flawless. The GRI model presented based on the Global Compact can only partially settle the problems associated with globalization (Kell & Levin, 2003). Their study argued that even though GRI standard could not provide a solution to global sustainability challenges, it can still play an imperative role in improving people’s lives around the world.

Conclusion

7.1. GRI Application and Implications in Africa

Unlike developed countries, GRI application in Africa is a new development as such it is confronted by many challenges. The African economy have certain unique features that differentiates it from other economies of the world. One such characteristics is that none of the developed economies (G7 countries) is found in Africa and only one of the G20 economies (South Africa) is based in Africa (Mustafa, 2016). That apart, the African economy is dominated by small and light industries. None of the Fortune Global 500 firms could be found in Africa (Morhardt, Baird, & Freeman, 2002).

However, since the institution of GRI some African countries have taken giant steps in its application though African economies have unique features peculiar to them that distinguishes them from other economies of the world. In Nigeria, there has been the introduction of environmental standards and guidelines for both the oil & gas and non-oil & gas sectors. For the oil & gas sector, EGASPIN (Environmental Guidelines and Standards for the Petroleum Industry in Nigeria) has been introduced. The non-oil & gas sector also have NESR (Nigerian Environmental Standards and Regulations) as its main environmental standard. In South Africa Visser (2005) stated that the adoption of GRI have seen the passage of corporate citizenship legislation from 1994 to 2004 to cater for its application.

7.2. Challenges of GRI Adoption

The implementation of GRI in Africa was faced by several challenges ranging from shortage of workers, employer-stakeholder relationship, sufficient provisions in GRI, sustainability problems, etc. Corporate social reporting (CSR) is a means of communication between a company and its stakeholders which indicates the company’s level of obligation to CSR (Fernandez-Feijoo, Romero, & Ruiz, 2014). However, an important concept is that Africa by far have the lowest number of registered companies with sustainability organizations internationally. The Table

Compared to global reporting on GRI, Africa’s proportion of GRI reporting in 12 years averaged 4.54% and a total of registered companies (1999-2010) with GRI of 268 (Table

Another test is that most organization compile constricted and incomplete reporting practices used to claim strong sustainability (Milne, Ball, & Gray, 2013). This is because the GRI’s integrated reporting system (TBL) is inadequate to report on organization’s sustainability. At best, they provide useful substitutes to other dimensions of sustainability disclosure. Inadequacy of reports has great effect on GRI diffusion of sustainability information (Marimon, del Mar Alonso-Almeida, del Pilar Rodríguez, & Alejandro, 2012).

Some of the problems encountered in the implementation of GRI in South Africa as suggested by Alonso‐Almeida, Llach and Marimon, (2014) include the fact that GRI adoption and implementation occurs simultaneously with the process of developing the GRI’s public sector supplement, was not based on any previous application from which the public sector could learn and it has no provisions for factors unique to South Africa.

Africa sustainability reporting according to Morhardt, Baird and Freeman (2002) on the economic and social aspects of GRI and the environmental indicators of ISO14031 were all below GRI and ISO14031 disclosure standards. Since 2000 when GRI came out with its first disclosure standard (G1), it has registered between 2,900 - 3,800 company members (Runhaar & Lafferty, 2009), while in Africa this total is 268 companies (Marimon et al., 2012).

7.3. Benefits of GRI Adoption

Notwithstanding the above challenges, there has been marvellous achievements recorded with the adoption of GRI in Africa. Some scholarships that scrutinizes the relationship between sustainability reporting using GRI indicators and some independent variable like total assets, gross earnings, number of firm branches, health & safety, waste management, community development, visibility, firm performance, etc.; came out with significant relationships (Akinpelu, Ogunbi, Olaniran, & Ogunseye, 2013; Ngwakwe, 2009; Oba, Fodio & Soje, 2012; Uwuigbe, Uwuigbe, & Ajayi (2011). In another study, the result of the application of GRI in South Africa showed that many of the decisions reached were without precedent in the South African context (Alonso‐Almeida, Llach, & Marimon, 2014). The advantages to companies that applied GRI include standardization, quality, comparability reporting, transparency, complements, other reporting initiatives and flexibility. Furthermore, enterprises have increased their participation in sustainability reporting standards with GRI but is relatively small compared to worldwide companies.

An assessment of the GRI environmental and social aspects of South Africa with that of some of the developed nations represented by the Fortune Global 100 showed that the regularity and level of CSR reporting in South African companies was meaningfully higher than that of the Fortune Global 100 (Dawkins & Ngunjiri, 2008). This is an indication that unindustrialized economies like South Africa may be more sympathetic to stakeholder concerns and social responsibility than peer “institutions in developed economies”. Visser (2005), who investigated on corporate citizenship in South Africa by examining the scope of academic research on corporate citizenship, recommended that GRI reporting is the chief catalyst for increasing corporate citizenship (legislation, globalization, stakeholder activism, etc.) and the over-all trend of CSR reporting and social investment. His study shows that South Africa has in no small way completed significant strides in corporate citizenship exercise. This is better established by the trends of sustainability reporting in South Africa by the top 100 companies from 1998-2003 (Table

Acknowledgments

My sincere thanks and gratitude to my sponsors Yusuf Maitama Sule University, Kano and the Tertiary Education Trust Fund for their moral and economic support for this research

References

- Adams, C. A. (2004). The ethical, social, and environmental reporting-performance portrayal gap. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability. Journal Emerald Insight, 17(5), 731-757.

- Akinpelu, Y. A., Ogunbi, O. J., Olaniran, Y. A., & Ogunseye, T. O. (2013). Corporate social responsibility activities disclosure by commercial banks in Nigeria. European Journal of Business and Management, 5(7), 173-185.

- Alonso‐Almeida, M., Llach, J., & Marimon, F. (2014). A closer look at the ‘Global Reporting Initiative’ sustainability reporting as a tool to implement environmental and social policies: A worldwide sector analysis. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 21(6), 318-335.

- Antoni, M., & Hurt, Q. (2006). Applying the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) for public bodies in the South African context: the eThekwini experience. Development Southern Africa, 23(2), 251-263.

- Barkemeyer, R., Preuss, L., & Lee, L. (2015). On the effectiveness of private transnational governance regimes-evaluating corporate sustainability reporting according to the Global Reporting Initiative. Journal of World Business, 50(2), 312-325.

- Bartelmus, P., & Cleveland, C. (2008, July 25th). Measuring sustainable economic growth and development. Environmental and Natural Resource Accounting. http://www.ecoearth.org/article/ measuringsustainbleeconomicgrowthanddevelopment

- Bell, J. & Lundblad, H. (2011). A comparison of ExxonMobil’s sustainability reporting to outcomes. Journal of Applied Business and Economics, 12(1), 17-29.

- Brown, H. S., De Jong, M., & Lessidrenska, T. (2009). The rise of the Global Reporting Initiative: a case of institutional entrepreneurship. Environmental Politics, 18(2), 182-200.

- Brown, H. S., de Jong, M., & Levy, D. L. (2009). Building institutions based on information disclosure: lessons from GRI's sustainability reporting. Journal of cleaner production, 17(6), 571-580.

- Carbonify.com (2014). What is Kyoto protocol? http://www.carbonify.com/articles/kyoto-protocol.htm

- Dawkins, C., & Ngunjiri, F. W. (2008). Corporate social responsibility reporting in South Africa: A descriptive and comparative analysis. Journal of Business Communication, 45(3), 286-307.

- Dingwerth, K., & Eichinger, M. (2010). Tamed transparency: How information disclosure under the Global Reporting Initiative fails to empower. Global Environmental Politics, 10(3), 74-96.

- Fernandez-Feijoo, B., Romero, S., & Ruiz, S. (2014). Commitment to corporate social responsibility measured through global reporting initiative reporting: Factors affecting the behaviour of companies. Journal of Cleaner Production, 81, 244-254.

- Fonseca, A. (2010, March). Barriers to Strengthening the Global Reporting Initiative Framework: Exploring the perceptions of consultants, practitioners, and researchers. In Trabajo presentado en Accountability through Measurement: 2nd National Canadian Sustainability Indicators Network Conference. Toronto. [Links].

- Initiative, G. R. (2013). G4 sustainability reporting guidelines. Global Reporting Initiative: Amsterdam, NY, USA, 3-94.

- Isaksson, R., & Steimle, U. (2009). What does GRI-reporting tell us about corporate sustainability? The TQM Journal, 21(2), 168-181.

- Kell, G., & Levin, D. (2003). The Global Compact network: An historic experiment in learning and action. Business and Society Review, 108(2), 151-181.

- Lamprinidi, S., & Kubo, N. (2008). Debate: the global reporting initiative and public agencies. 326-329.

- Levy, D. L., Brown, H. S., & de Jong, M. (2010). The Contested politics of corporate governance the case of the global reporting initiative. Business & Society, 49(1), 88-115.

- Malarvizhi, P. & Yadav, S. (December 2008/January 2009). Corporate environmental disclosures on the internet: an empirical analysis of Indian companies. Issues in Social and Environmental Accounting, 2(2), 211-232.

- Marimon, F., del Mar Alonso-Almeida, M., del Pilar Rodríguez, M., & Alejandro, K. A. C. (2012). The worldwide diffusion of the global reporting initiative: what is the point? Journal of Cleaner Production, 33, 132-144.

- Milne, M. J., & Gray, R. (2013). Whither ecology? The triple bottom line, the global reporting initiative, and corporate sustainability reporting. Journal of business ethics, 118(1), 13-29.

- Morhardt, J. E., Baird, S., & Freeman, K. (2002). Scoring corporate environmental and sustainability reports using GRI 2000, ISO 14031 and other criteria. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 9(4), 215-233.

- Mustafa, J. (2016, September 3rd). What is G20 and how does it work? The Telegraph Business. http://www.telegraph.co.uk/business/0/what-is-the-g20-and-how-does-it-work/

- Ngwakwe, C. C. (2009). Environmental responsibility and firm performance: evidence from Nigeria. International Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences, 3(2), 97-103.

- Oba, V. C., Fodio, M. I., & Soje, B. (2012). The Value Relevance of Environmental Responsibility Information Disclosure in Nigeria. Acta Universitatis Danubius. Œconomica, 8(6).

- Runhaar, H., & Lafferty, H. (2009). Governing corporate social responsibility: An assessment of the contribution of the UN Global Compact to CSR strategies in the telecommunications industry. Journal of Business Ethics, 84(4), 479-495.

- Uwuigbe, U., Uwuigbe, O., & Ajayi, A. O. (2011). Corporate Social Responsibility Disclosures by Environmentally Visible Corporations: A Study of Selected Firms in Nigeria. European Journal of Business and Management, 3(9), 9-17.

- Visser, W. (2005). Corporate citizenship in South Africa: A review of progress since democracy. The Journal of Corporate Citizenship, 18, 29-38.

- Willis, A. (2003). The role of the global reporting initiative's sustainability reporting guidelines in the social screening of investments. Journal of Business Ethics, 43(3), 233-237.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

02 August 2019

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-064-8

Publisher

Future Academy

Volume

65

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-749

Subjects

Business, innovation, sustainability, environment, green business, environmental issues

Cite this article as:

Haladu, A. (2019). Challenges of Gri Sustainability Disclosure Standards Adoption by Africa’s Two Largest Economies. In C. Tze Haw, C. Richardson, & F. Johara (Eds.), Business Sustainability and Innovation, vol 65. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 1-12). Future Academy. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2019.08.1