Abstract

The article reveals the peculiarities of the linguistic structure of American political advertising which are used to convey implicit meanings. It deals with hidden senses in rhetorical figures which are typical of the advertising text. The research is based on the theory of conceptual integration, or blending, implemented by Gilles Fauconnier and Mark Turner. Rhetorical figures are interpreted as independent blends capable of forming the meaning which sometimes differs from the explicitly pronounced text and are used intentionally to influence the recipient in a far-reaching way. The complex cognitive operations that serve as cross-space mapping between input spaces are first of all connected by some common elements in the generic space and only then lead to the formation of the blend, which is easily deciphered by the audience due to the fact that the process of blending is very common to our mind and always occurs when we transfer or get new ideas. Rhetorical figures in advertising can function independently without taking the visual picture into account or be closely connected with it, forming just a part of a more expanded blend. Nevertheless, intricate linguistic structures exert more influence on the voters than common words and phrase as the more unusual the linguistic means sounds, the more complex operations the brain performs and, as a result, the more memorable it becomes.

Keywords: Blendinput spacesgeneric spacepolitical advertisingrhetorical figures

Introduction

In the modern world advertising is a tool of psychological manipulation over the human consciousness. This phenomenon has not only become an integral part of the modern society, but has also started to determine and dictate ethical, social and political attitudes. To create a positive image of the advertised item or service, advertisers, or sponsors, appeal to people’s feelings and emotions thus playing on their interests and wishes. Most researchers consider advertising as the process of communication between the consumer and the advertiser with the aim not only to give the information about the item or service but also to exert influence, to involve consumers into the advertising communication process, to create a desire and to persuade them in the necessity to make a purchase. Turow (2018), in the broadest sense, defines advertising as attempts to persuade people to adopt certain ideas or purchase particular services or goods. In a narrow sense, he considers advertising as messages that appear as a result of the explicit purchase of time or space on certain channels, or media. In this article we are going to talk about television advertising, or a commercial. This notion differs from advertisement which implies online display or print advertising.

Without doubt, television advertising has its own peculiarities as it combines text, sound and video picture. The involvement of a bigger number of senses has more impact on the mind because more cognitive processes are working at the same time. The more difficult and diverse tasks the mind has to handle, the more these tasks stick in people’s memory. The most common and typical advertising task which our brain has to tackle is the frequent repetition of rhymed words and slogans applied to well-known settings, like everyday situations, scenes from famous films and cartoons, and accompanied by catchy melodies and songs.

Political advertising

Commercials are used in different spheres of life including the political one. Television and the Internet are certainly the most popular media for political campaigning and, as a result, political advertising has developed into one of the most influential sources of political communication. The goals of political advertising are different: to facilitate somebody’s rise to power, to sustain a positive image of a politician or a party inside the mind of voters, to embed a certain idea or initiative into public consciousness, to gain support, to reveal political views and beliefs and even to discredit an opponent. Political advertising can be defined as advertising whose central focus is the marketing of attitudes, ideas and concerns about public issues, including political concepts and political candidates. The main goal of this type of advertising is to gain the confidence of the people for their acceptance of ideas and to influence their vote (Glavaš, 2017). Goals of advertising are closely connected with its functions. Grinberg (2012) points out the following: informative (to inform the audience about the forthcoming political event; to introduce the candidate, party’ program; to reveal political views, offers, advantages), communicative (establish rapport between power holders or contenders for power and people), socially orienting and ideological (to highlight the object of advertising and their viewpoint on social issues and ways of solving).

To have a desirable effect on viewers, 30-second commercials are elaborated so thoroughly that their impact is very strong. In general, several types of psychological impact can be distinguished: emotive (inducement to feelings and emotions), cognitive (communication of information), conative (behavioural influence), suggestive (hypnosis) (Romat & Senderov, 2016). Psychological impact is based on certain techniques used to attract the audience. Pesotskiy (2014) mentions such technics as: 1) unique character of the selling proposition (difference between this object of advertising and others); 2) frequency (repetition of the same advertising clip without changes); 3) intensity (use of close-up, large fonts of slogans on the screen, off-text with accentuation on some words and phrases); 4) dynamism (viewers pay more attention to fast-moving objects, than to motionless); 5) contrast (the object of advertising should stand out on the general background); 6) size (contrast ratio of the advertising message); 7) emotional intensity (any advertising should cause only positive emotions).

Political advertising in the USA

Commercials are a dominant part of the political marketing and it is especially true about the U.S. political advertising. The reason why political advertising has rooted in the USA can be traced in its Constitution. Unlike other Western democratic countries, such as Russia, France, Germany, the UK and others, here the number of regulations and restrictions on political advertising is limited because this marketing tool is protected as a form of free speech (Kaid, 2008).

A common American phenomenon is negative advertising. It is more popular and even more often used than positive one. This statement contradicts to the seventh advertising technique (emotional intensity) mentioned by Pesotskiy (2014). According to him, ads should arouse only positive emotions. Negative advertising in its turn criticises with different degrees of negativity the policies, the performance and even the character of the opposing candidate or party (Davis, 2017) and thus brings negative attitude. Some studies prove that negative ads are more powerful, others claim that positive advertising has better effects, and, finally, some studies found no differences in effects between negative and positive ads at all (Moorman & Neijens, 2012).

Problem Statement

It is obvious that advertising influences our decisions and way of thinking. Even video pictures without text are capable of delivering a message. Peculiarities of a video picture deserve a special attention and are thoroughly studied in our article “Visual Means of Impact in American Political Advertising” (Kovalchuk, 2016). In this research we are concentrating on the impact of text and rhetorical figures which are used to make this impact strong. The main problem is to find the mechanism that makes our mind so responsive and vulnerable to advertising text and define the most common linguistic means and cognitive processes that help text be so influential.

To solve this problem, we turned to Fauconnier and Turner’s (2006) theory of conceptual integration or blending. Blending is the process that is going on unconsciously, but it forms the basis of our thinking. The scholars declared the advent of the ability to blend things in our mind to be an important leap in evolution and a decisive factor in the development of speech.

Blending operates almost entirely below the horizon of consciousness. We usually never detect the process of blending and typically do not recognize its products as blends. Very rarely, the scientists can drag a small part of blending onstage, where we can actually see it. (Turner, 2014, p. 18)

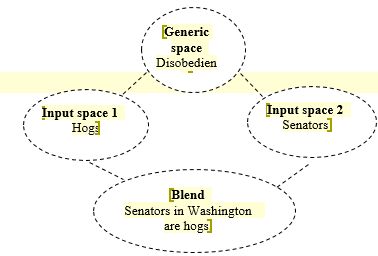

Blending is based on the juxtaposition of two things, ideas or objects which are usually considered as separate mental spaces. When these counterparts are blended in mind, in other words when we compare them, their common features, or elements, form another mental space – generic one. With the help of the cross-space mapping all these three mental spaces interact with each other and lead to the creation of a new mental space – blend. This is how new ideas, words and sentences appear (Fauconnier, 2017).

The theory of conceptual integration comes from the theory of conceptual metaphor which includes a two-space model of mapping from the source domain to the target domain (Fauconnier & Lakoff, 2014). Fauconnier and Turner (2006) add two more spaces to the source domain and the target domain, thus making the process more complete. Conceptual metaphor theory studies metaphor not only on the linguistic level but also on the level of cognition and activity (Lakoff & Johnson, 2003). The theory of blending is not limited to cognitive metaphors. It covers a huge variety of linguistic and nonlinguistic means.

Research Questions

The process of blending is typical of political advertising, as all ads are usually based on comparing different things, political ideas and even candidates. Things, ideas and people present separate mental spaces. Their comparison is based on finding some common features and some differences which form a generic space. The result of such comparison is a newly emerged blend that serves for the purposes of advertising. But what linguistic means are used in this process? What is their role in forming advertising blends? How do blends emerge on the verbal level? How do verbal mental spaces coincide with nonverbal ones, like video picture and background sound? Do they merge with each other to yield another blend? How are all these processes reflected in our mind? To answer these questions, it is necessary to study the peculiarities of the linguistic means used in advertising text.

Purpose of the Study

Text of TV commercials is always creative and unusual. It can be presented in the written or oral form. Text is relevant for introducing the object of advertising, describing its main characteristics and persuading viewers to make a choice. The written text tends to highlight the most relevant features of the advertised object and almost always contains slogans. It backs up or reflects the information that has already been pronounced or is being pronounced at the same moment as words are appearing on the screen. In this case, main ideas (names, numbers, slogans and others) are highlighted on the graphical level: variable fonts, capitalization, underlining, coloring and so on. On the linguistic level, main ideas can be stressed out with intonation, word ordering or rhetorical figures. The purpose of this study is to analyse different rhetorical figures of latest American political ads (2014–2018), describe the processes of their conceptual integration and find out how these processes influence our mind. The research is aimed at determining input spaces, finding common elements that are included in the generic spaces and studying the yielded blends.

Research Methods

Advertising text can influence the viewer explicitly and implicitly. Explicit impact presupposes a direct call for choosing the candidate or vivid and positive description of the candidate’s character and political beliefs (

Rhetorical figures of thought like metaphor, metonymy, synecdoche and others can be analyzed as results of the compressions brought about by blending. According to Turner (2014), “the classical rhetorical labels for all these things are useful as shorthand for picking out different reactions, but yet, that long list of labels can obscure the common underlying mental process” (p. 142). In other words, notwithstanding what linguistic means is analyzed, the scheme of analysis is the same. A wide range of these means in advertising text makes it simple, well-directed and catchy.

Metaphor

Metaphor is without doubt the most spread linguistic means. In political advertising it often helps to cover up the political content or make it more comprehensible for all voters. For example, State Sen. Joni Ernst starts her advertising by saying

In the 2018 advertising clip ‘Dumpster Fire’ the scheme of reconstructing hidden senses is more complicated. From the linguistic point of view, the situation in the Senate is compared with the inferno:

Nevertheless, the constructed blend does not reflect the main sense of the commercial. This advertising contains some other meanings as well. If the Senate is fire or inferno, than Richard Painter is water. Minnesota is known as the land of lakes, so it is logical that the candidate from this state is associated with water. Such association appears when gallons of water are poured on the fire in the video. The video picture isolated from words does not make sense, only the phrase

Two blends ‘Washington Senate is a dumpster fire/inferno’ and ‘Richard Painter is water/lake’ are related to each other. They are combined with common elements from the sphere of politics and elections into the Senate. Their interaction makes them input spaces for the blend ‘Richard painter is a good candidate for the Senate from Minnesota who can fight against the dumpster fire in Washington’. So, two first initial blends form another one which serves as the main idea of advertising.

Epithet

The research has showed that epithets are mostly used in negative advertising. In positive ads the candidate or the party will never praise themselves; as a rule, they use the airtime to convey main facts about their policy. But in negative ones, epithets are a good way to discredit the opponent and stand out against them.

The clip ‘Shady’, directed against Rick Scott, first of all reveals his political failures and then ends up with the phrase “

In Donald Trump’s campaign ad ‘Don’t Let Hillary Clinton Do It Again’ the use of epithets “

All these blends are not strongly connected with the video picture and can be understood without its employment. Video excerpts with politicians’ speeches serve only as a proof of their lie.

Allusion

Implicit meaning can also be conveyed with allusion. Let us consider the first example. The clip ‘Casey’ starts with Ronald DeSantis’s wife saying: “

The role of video is also great in the negative commercial ‘Philadelphia International Airport’ where dissatisfying Clinton’s policy is projected on suitcases on the carousel (

Findings

In this article we give examples of blending process taken place only in metaphors, epithets and allusions, but the analysis of other rhetorical figures (personification, rhetorical questions, zeugma, parallelism and so on) have shown that all of them are formed in the same way. They are all based on the mixture of two different ideas which form two input spaces for the blend. The juxtaposition of these ideas is based on some common features that are mapped into the generic space. In political advertising the generic space is often formed by elements from the semantic sphere of politics and election. The cross-space mapping between all these mental spaces yield a blend. Sometimes several blends are needed to form the final blend that carries the main idea of the advertising.

This blending process happens automatically and subconsciously. The mapping of strange and unusual ideas takes more effort for the brain to process this information; as a result, this blend sticks more in our mind. This is the reason why sponsors often use rhetorical figures. They are catchier as they create more unusual images. Different types of rhetorical figures (lexical and syntactical) can take part in this process. Mostly it is the rhetorical figure itself that conveys the main meaning of advertising. Rhetorical figures carry implicit meanings, but hidden senses are revealed due to the blending process, which is vital for advertising, especially political one, as every word there is weighed up by voters and can determine the future of people.

In some commercials, linguistic blends can be closely connected with the video picture. In this case, the video picture forms the third input space for the blend thus helping to reconstruct the meaning (like in ‘Casey’ or ‘Philadelphia International Airport’). In other clips, it just serves as an illustration of the linguistic blend which can be easily understood without any video (‘Shady’), in other words, the picture plays the role of a separate mental space. It still remains very important for the advertising, but it means that the verbal blend can function independently.

Dark background in the video is a typical feature of a negative advertising. It generates a strong feeling of rejection as well as unpleasant background music does. Soundtrack matters a lot, it forms a separate mental space. To sum up, verbal text, non-verbal text, video picture and sound are all separate mental spaces that interact with each other and become input spaces for the advertising clip. Our brain analyses all these spaces and delivers up the main sense which was intended to be conveyed by the advertiser.

Conclusion

The role of advertising can hardly be overestimated. It has a strong impact on our choice and ways of thinking. For the recent years, political advertising has become the form of art. Politicians appeal to ads to reach different goals: to reveal their ideas, to make a name or even to blacken their opponents’ reputation. Nonstandard approaches are implemented on all levels of adverts.

TV and the Internet are the most popular media platforms for political advertising. In the United States, political commercials have become the dominant form of communication between politicians and the public. Half of campaign budgets is spent on it. In Western countries, where regulations restrict content and time periods of political TV ads, the role of this type of advertising is not so influential.

Moreover, in many Western countries it is forbidden to discredit opponents in the campaign, while a great number of American politicians resort to the use of negative advertising. It still remains obscure whether the effects of negative adverts are more powerful, but, without doubt, they can generate a boomerang effect (Hughes, 2018), when voters’ disapproval of bashing might result in negative perception of the sponsor.

Notwithstanding the type of advertising, it is always based on this or that rhetorical figure. A wide range of various linguistic means, in combination with video picture and sound, generate a strong mental effect and can determine the voters’ choice. Their cognitive impact has not been thoroughly analyzed yet and opens up great opportunities for further studying.

References

- Davis, B. (2017). Negative Political Advertising: It’s All in the Timing. Retrieved from https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/79449/1/MPRA_paper_79449.pdf

- Fauconnier, G. (2017). Mental Spaces, language modalities, and conceptual integration. The New Psychology of Language: Cognitive and Functional Approaches to Language Structure.

- Fauconnier, G., & Lakoff, G. (2014). On Metaphor and Blending. Cognitive Semiotics, 5, 393-399. https://dx doi.org/

- Fauconnier, G., & Turner, M. (2006). Mental Spaces: Conceptual Integration Networks. In D. Geeraerts (Ed.), Cognitive Linguistics: Basic Readings (pp. 303-371). Berlin, Germany: Mouton de Gruyter.

- Glavaš, D. (2017). Political advertising and media campaign during the pre-election period: A Comparative Study. Retrieved from https://www.osce.org/mission-to-montenegro/346631?download=true

- Grinberg, T. EH. (2012). Politicheskie tekhnologii. PR i reklama [Political technologies. PR and Advertising]. Moscow: Aspekt-Press.

- Hughes, A. (2018). Market Driven Political Advertising: Social, Digital and Mobile Marketing. Switzerland: Springer International Publishing.

- Kaid, L. L. (2008). Political advertising. In W. Donsbach (Ed.), The international encyclopedia of communication (pp. 3664–3667). Oxford, UK: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Kovalchuk, L. (2016). Visual means of impact in American political advertising. Russian Linguistic Bulletin, 4(8), 96-100.

- Lakoff, G., & Johnson, M. (2003). Metaphors we live by. Chicago: The University of Chicago press.

- Moorman, M., & Neijens, P. (2012). Political advertising. In E. Thorson & Sh. Rodgers (Eds.), Advertising theory (pp. 3-17). New York, NY: Routledge.

- Pesotskiy, E. (2014). Reklama [Advertising]. Rostov-na-Donu: Feniks.

- Romat, E.V., & Senderov, D (2016). Reklama. Prakticheskaya teoriya [Advertising. Practical Theory]. Saint Petersburg: Piter.

- Turner, M. (2014). The Origin of Ideas. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Turow, J. (2018). The development of the modern advertising industry. In J. Hardy, H. Powell & I. Macrury (Eds.), The Advertising handbook. New York, NY: Routledge.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

07 August 2019

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-065-5

Publisher

Future Academy

Volume

66

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-783

Subjects

Communication studies, press, journalism, science, technology, society

Cite this article as:

Kovalchuk*, L. (2019). Revealing Hidden Senses In American Political Advertising. In Z. Marina Viktorovna (Ed.), Journalistic Text in a New Technological Environment: Achievements and Problems, vol 66. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 146-154). Future Academy. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2019.08.02.18