Abstract

The article discusses local initiatives aimed at development of national education of the Ural people. A wide range of activities included opening national schools and colleges, training teachers, organizing courses to improve teaching skills, etc. Local teachers, librarians, doctors, priests and other people took part in all of these events. Zemstvos spent most of the budget on public education. Local governments spent quite a lot of money on the construction and opening of public schools, the heating and lighting of these schools, furniture, books, stationery, etc. A significant feature of the educational policy of the Ural was a systematic concern for the education of the non-Russian population of this multinational region. It was made due to the objective requirements of economic development. In the period under study, public education has become more accessible at urban and rural levels, seriously contributing to the training of qualified specialists for various sectors of the economy. Having created a network of cultural and educational organizations and institutions, zemstvos increased the general educational and cultural level of masses, their moral and aesthetic education, attracted people to actively participate in political and public life of the country, influenced the strengthening of friendship between nations, etc. Also, the authors describe the appearance of the teacher, which was not diverse. Historical experience of zemstvos in development of national education should be used by modern local governments. Only comprehensive development of the local government is able to awaken the economic and social initiative of the population.

Keywords: Uralzemstvoseducationnon-nativesteacherimage

Introduction

Ural is a unique region, large and multinational, it plays a significant role in the socio-political life of the country. At the beginning of the 20th century, local governments set themselves the difficult but necessary task of developing national (non-native) education in this region.

Problem Statement

The beginning of the 20th century is a controversial period both for Russia and for the regions. Revolutionary movements, the First World War, the unstable situation in the world, dissatisfaction forced the government and local authorities to find ways to settle difficult situations. The education issue, including the national (non-native), was a successful attempt to distract the public from the course of events in the country, to change the people' activities in a more positive direction, to ease the tension among the masses, and also to solve the urgent problems. In an incredibly difficult, even critical situation for Russia, the measures aimed at the development of national education have not only succeeded, but have borne fruit.

Research Questions

The subject of this study is the process of learning in the schools for non-natives and teachers' training for these schools.

Purpose of the Study

The purpose of the study is to study activities of local authorities aimed at the development of a multinational population in education and culture in the Urals.

Research Methods

Research methods that were used are the following: historical descriptive, historical and chronological, historical and biographical, comparative method, as well as analysis’ and synthesis’ methods.

Findings

In connection with the opening of a significant number of schools in the Ufa province, the authorities had to take into account the fact that 60% of the population of the province were non-natives. Teachers at these schools were trained at the Kazan teachers' school, but there were clearly not enough of them. This situation contributed to the opening a Tatar school for teachers in Ufa. The Kazan teacher’s school became a prototype for the Tatar school in Ufa, with scholarships for students and financial support from the state. Periodic pedagogical courses that emerged at the end of the 19th century became even more widespread at the beginning of the 20th century. Such courses were organized on the initiative of zemstvos, individuals, or urban communities. Inspector of public schools formed a group of students, the number of which claimed the Chief Monitor.

On the territory of the Russian Empire in 1907, the number of temporary (one-year) pedagogical courses reached 90, of which 8 operated in the Orenburg school district. However, practice has shown that this period of study is not enough. On the initiative of the Ministry of Public Education, they issued Rules for organizing and conducting pedagogical courses, with an extended period of study of two and three years. Such courses became widespread and, by 1912, there were already nine of them in the Orenburg school district.

Local authorities paid attention to the field of education, they actively involved non-natives into the study process. It is a well-known fact there were not enough teachers at these schools. This fact forced the Ural authorities to organize training courses for teachers from the Muslim community. Head of the three-year courses Kondakov V.A. opened the courses in Ufa in 1917 and actively involved listeners. In January of 1917 there were 19 people, but by the summer of the same year there were already more than 100. Training courses for teachers of Russian-Tatar and Bashkir schools have started at that time. In addition, the authorities supported the participants of the courses with a scholarship of 20 to 100 rubles, as was done at the Belebeyevo district council. However, such assistance from the state obliged future teachers to work 2 years as a teacher. Future teachers attended such courses as religion studies, history, science, drawing, Tatar language and other disciplines. The most famous teachers of these subjects were S.M. Yuriev, P.A. Sokolov, G.G. Teregulov and others. The provincial zemstvos allocated money for the maintenance of courses, for example, for the Ufa' zemstvo, which in 1917 spent 11910 rubles on the organization of such events.

In addition, the training of teachers was not only about long courses, but also the later opened short courses in the village of Verkhniye Kigi. The initiator was the Zlatoust district council in 1917, which was ready to provide the building of the 2-grade school and allocations in the amount of 4,700 rubles. Ufa's local authorities, keeping in mind a catastrophic shortage of teachers in foreign schools, supported the actions of this zemstvo.

However, Ufa was not the only one province where staff for non-natives' schools was trained. In 1917 Orenburg organized retraining of Muslims in the amount of 250 people from various regions: Siberia, Turkestan and etc. S. Shakulova led the process, she had a degree in pedagogics, and she has made an internship abroad which was really rare for that time. The traditional program of courses included the study of the native language, gymnastics, methods, school hygiene and other subjects. Orenburg was famous also because of long courses for teachers. As part of one of these courses, Chelyabinsk Zemstvo spent 4,000 rubles on established scholarships (Allied thought, 1918). In addition to training courses for teachers of Muslim schools, a Russian-Bashkir women' and boarding school for 83 women was organized from local budget resources.

The importance of existing of such courses and schools is difficult to overestimate, they all led to a qualitative and quantitative growth of qualified teachers for non-natives' schools. Taking into consideration the active development of public education, it is impossible not to mention the people who led the schools, such as A.Ya. Mikhailov, A.V. Milyukov A.A. Aydarov and many others. Thanks to zemstvos, 8897 schools were opened with a total number of students of 1,447,136 people. It was local governments, such as zemstvos, that promoted the development of vocational and school education, illiteracy among ordinary people was rapidly eliminated, and their cultural level significantly increased.

It is impossible not to mention the huge funds within their budget, which the Orenburg and Ufa zemstvos spent on education. As an example, in table

The Ural zemstvos set many tasks, one of which was the enlightenment of the foreign population in such a multinational region as Ural. This task was substantiated by the development of the economy at the beginning of the 20th century. If summing up the intermediate results, they will be as follows. The Zemstvos managed to organize and conduct 68 training and retraining courses for Russian-Bashkir and Russian-Tatar schools in Ufa, Orenburg, Vyatka, Perm, Troitsk, and other cities. (Perm government, 1915). It is important that school and vocational education in the study period expanded to more new cities and villages.

table

Zemstvos managed to establish and financially ensure systematic national readings and lectures, which were rare until 1914. Folk readings were gaining popularity, which indicates the genuine public interest. Zemstvos gathered meetings to develop a plan for organizing these events. Meetings were held in Ufa, Zlatoust, Birsk, Menzelinsky counties. These meetings were held during the First World War, which means their significant influence on the development of the general cultural level of the population. At meetings, it was established that library committees take on the responsibility of organizing public readings, they selected readers, lecture and readings topics, and the county zemstvos supported lecturers financially, provided magic lights and rooms for readings.

Table

Reading and lectures were held in schools, libraries, government buildings. Interest in such events is growing rapidly. In the 1914-1915 almost 104,000 people attended them, mostly children and teenagers. In order to interest people in such readings, they were specialized, that is, devoted to agricultural topics, addressing issues of agronomy and other topics. In some zemstvos a post of a lecturer was established for these readings.

Then, it was necessary to select qualified lecturers in these areas. Orenburg zemstvo government held a special meeting on the appointment and selection of candidates to be public lecturers with a salary of 5 rubles for 4 lectures, which led to an increase in the expenses of the zemstvos. In 1918, 9,680 rubles were spent on public reading.

The readings were most often held in Chelyabinsk oblast. Local intelligentsia, librarians and priests were responsible for that. The county libraries hosted popular readings with great pleasure, as evidenced by the data. In 1917 there were more than a thousand of them, in various fields - history, politics, geography, agriculture, religion, etc. The following representatives of the Urals intelligentsia were famous lecturers - I.P. Panasyuk, O.I. Olshevskaya, Ahmed-Migdad Kurbangulov, E.N. Krupitskaya, Yu.N. Scheglova, I.P. Proskuryakov, L.S. Kushov, V.I. Menshikov, N.F. Nichiporovich, I.I. Voitov, L.Ya. Bukharin, M.G. Vitrishchak, M.I. Usova, M.N. Viksnit, P.N. Kudyurov, A.N. Gorokhov and others. Thanks to public lectures and readings, was formed an active citezinship of the population regarding the political, economic and social situation in the country and the region, along with the general cultural level.

Another interesting area of the Zemstvos' work was opening and support of drama clubs and creative associations. Chelyabinsk had 11 drama and 18 educational clubs. In Chudinovo village, drama club was run by the library manager P.N. Suvorov, educational club in Travyanskoe village was run by A.O. Babikov. Sometimes, due to the lack of qualified leaders, one specialist ran clubs in several villages at once. For instance, F.A. Serebrennikov ran drama clubs in Beloyarskoye, Kislyanskoe and Karachelskoe villages, P.V. Chadayev ran clubs in Kosulinskoye, Polovinnoye, Petrovskoye, Bolshaya Riga villages and in Olkhovka village and this was a common thing.

In the Orsk County, Abdulyasovo village (Muslim), representatives of the zemstvo ran drama clubs themselves, and taking into account the specificity of the settlement, they staged plays in their native language "Kibirgi", "Aldalyk and Aldandyk", "Branch Theater", separately to men and women. The work and performances of employees of these institutions received mixed reviews, from very positive to neutral but not so often.

Yet drama clubs were warmly welcomed by the public. A folk drama club was opened in the department of public education in Ufa in 1917. This drama club had a repertory company that visited the nearby counties. This activity led to close collaboration with regional drama clubs. Drama clubs were in every county. Moreover, activists organized workshops on stage speech, acting skills, lectures on theatrical art for educators and public during winter and summer holidays.

The genuine interest of people in theatre made the Orenburg zemstvo to apply to the local government for funding of the posts of theatrical instructor and equipment keeper, with a total cost of 1920 rubles per year. There were no these kind of specialists in the county, therefore, there were invited from Orenburg (Orenburg Zemstvo, 1916).

It was difficult to open national theaters in Chelyabinsk County, the allocated funds not always covered all costumes and scholarships. In addition, the performances were staged in small buildings - private houses or libraries. But despite the difficulties, in 1917, 12 performances were staged with a presence of local residents, teachers, and librarians. The repertoire was extensive: A.P. Chekhov, A.S. Griboedov, N.V. Gogol and others. Thanks to getting familiar with theatre art, the population widened their outlook and enhanced their cultural level.

The portrait of a teacher of the beginning of the 20th century is of particular interest. Costumes in the period under review are almost the same, due to the availability of clothing and fashion trends. Now clothes had to be comfortable, convenient, and not demonstrating wealth or belonging to a particular strata. However, the income of the teachers was low, and the pedagogical ethics did not allow to dress fancy, clothes had to correspond to the owner. The most important characteristic of clothing was convenience. Traditionally, the woman’s costume was a blouse in combination with a long skirt; this applied to young ladies regardless of the type of work (Minenko, Apkarimova, & Golikova, 2006).

The leading role played accessories. They could indicate the position of women in society. At the same time, Ural is still a province, and this could not but affect the quality and availability of clothing. Remote regions not always managed to keep up with fashion, therefore, clothes were somewhat old-fashioned.

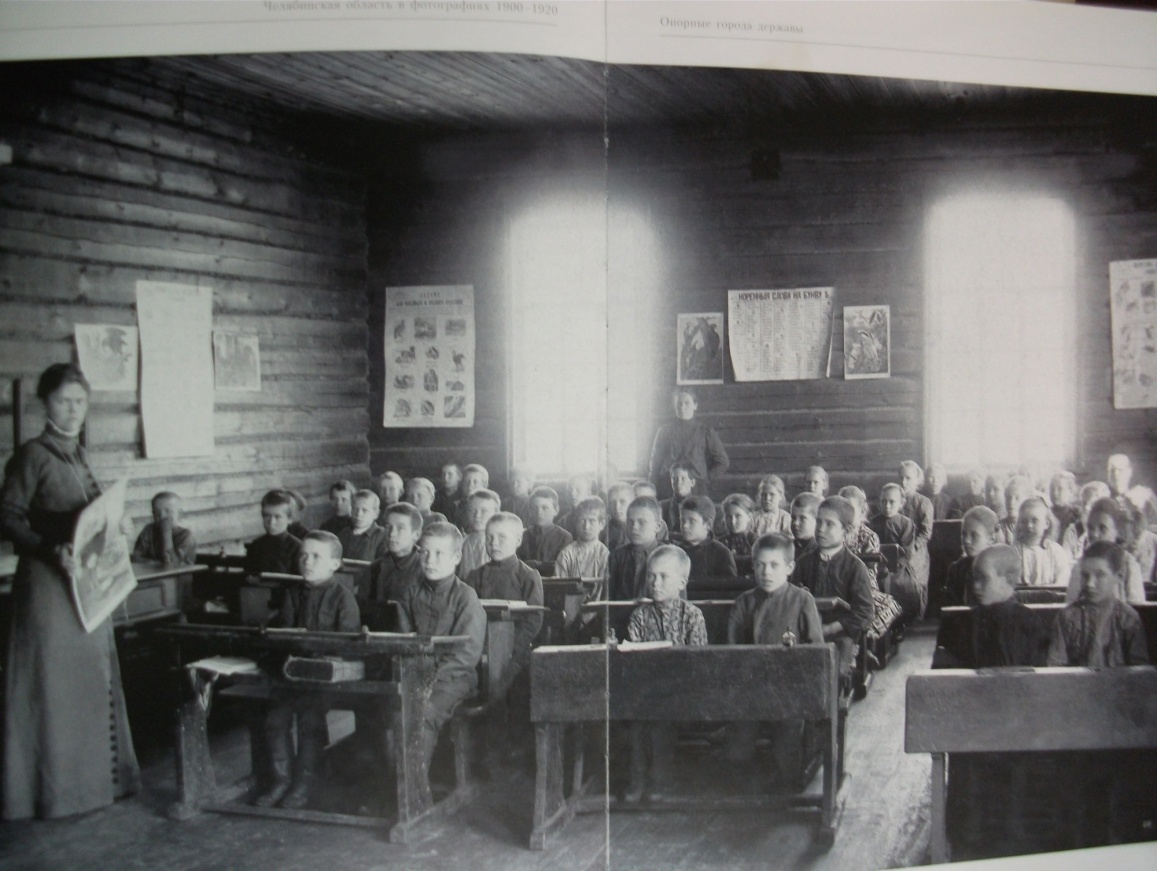

There is not enough material on the description of teachers’ clothes. That was preserved in the form of photographs in archives. The image of a female teacher is represented at photo 1. This photo shows a teacher of an elementary school in Satka, 1908–1912. She has a long dress in a dense fabric, with fully closed hands and a high neck, decorated with a white collar. The dress is decorated with asymmetrical large buttons. The waistline is accentuated with a wide belt. She also has a minimalist accessory - a long chain with a pendant.

This image is unique, it gives an idea of what subject the teacher is currently teaching, judging by the image on the paper it is natural science; as well as we can see the situation in the classroom and even the students, how many of them are in the class and what gender they are.

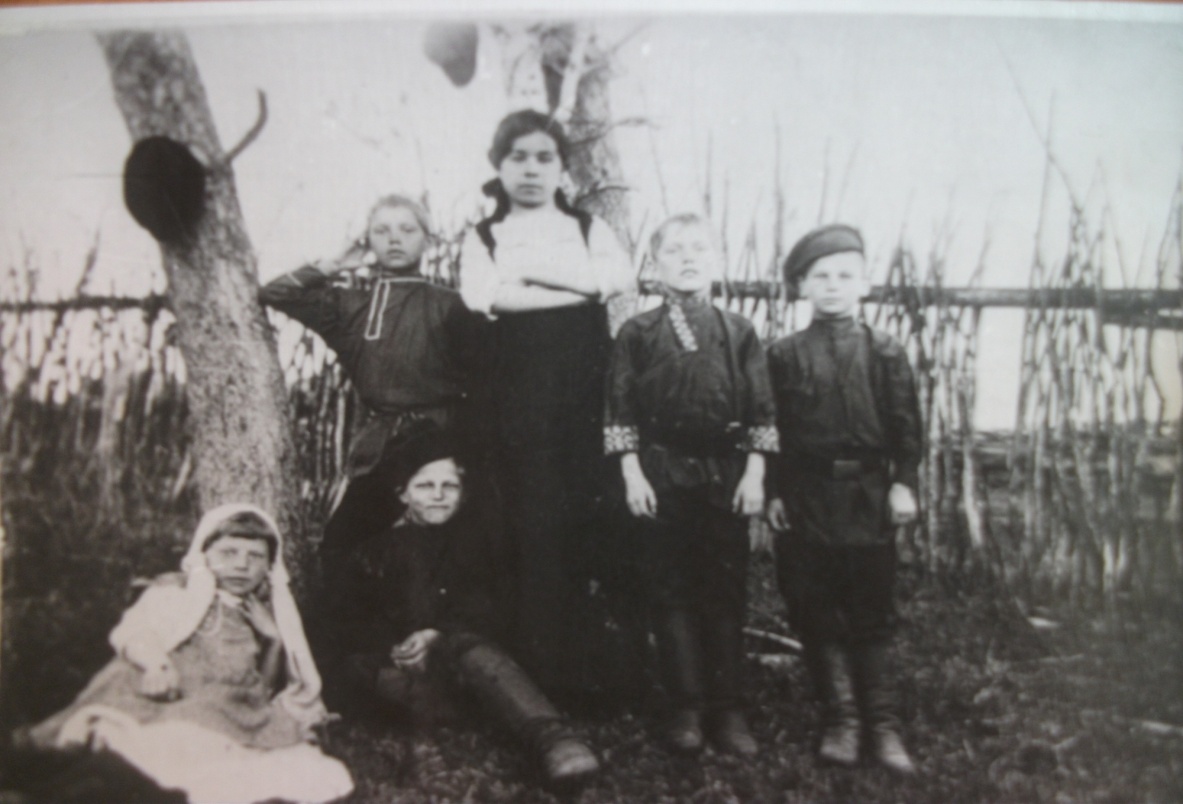

Another example of women's clothing and the image of a teacher at the beginning of the 20th century is presented on Photo 2, which is from the Zlatoust archive. According to this photo, the teacher M.V. Shevelina wears white sweater and a dark long skirt. Preference was given to a short sweater, which was worn to the prom. The teacher could wear clothes as monochromatic colors, as well as decorated with any pattern, but without any vulgarity. The skirts could be decorated with both horizontal and vertical pleating, or they could have a line along the very edge of the skirt.

It is necessary to take into account the fact that could affect the appearance of the teacher - a noble or rich husband. Wives, teachers with reach spouses could afford a dress made of velvet, but again, without any frills.

Women always went on public with their head covered, instead of hat they used a scarf in the warm season and a warm knitted shawl in winter. As for the shoes, there was no variety at all. Boots for summer and valenki for winter. According to these photos, we give the characteristic of women's hairstyles in the study period. If a woman did not put her hair under a scarf or shawl, then she brushed them smoothly, gathered them in a tight bun on the back of her head, as shown in photo 1. On special occasions, the teacher could brush hair in the tail at the back of the head, not twist them and leave loose on the shoulders, as depicted in photo 2. There was another option for styling women's hair, braids in the form of a crown. Due to certain circumstances, teaching stuff at school was predominantly females, so we studied the female image, but men also were principals or a teachers. There are practically no photographs of male teachers, except for a unique photo of Ufa teachers from the beginning of the 20th century.

Men's suit was made of cloth mainly from dark colors. Men wore a Russian national shirt, as shown in photo 2. When sewing a shirt, natural linen and cotton fabrics were used, both plain and patterned (Adukova, 2004). Shirts were worn mostly for celebrations or by the representatives of leadership positions. The head was covered with caps, hats or service caps as shown in photo 3. Men almost always wore a beard.

Thus, the appearance of teachers was modest, and sometimes even sad. The income of the teachers was too low for frills in accessories, and the choice of fabrics in the period under study was limited. It was possible to wear only black or gray standard suit for men, and for women - dark dresses and skirts to the floor. The only exceptions were holidays, for which teachers wore light-colored clothing. Also, teachers could afford some jewelry, wedding rings, thin chains and modest pendants.

The financial and social situation of teachers directly depended on the school and its location. Schools prefer to hire a graduate of a teacher’s institute or seminary, who according to statistics, in 1911, were 48% of the total number of teachers, 31% had secondary education, the rest were below average or had no special pedagogical education. These figures are typical for male graduates, among female graduates, the situation was even worse. Only 20% were graduates of a teacher's seminary, a high school gymnasium certificate had 63% of them, the rest were admitted to the pedagogical activity after passing the examination of vocational abilities. However, personnel with higher and secondary education almost did not reach small cities and villages. Therefore, in small cities there was a severe shortage of teaching staff.

Graduates did not seek to return to their native village or county, guided by youthful maximalism, they remained in large cities and tried to realize themselves there. In villages teachers had to work for very low wages, sometimes the teacher was forced to take food aid from the parents of his students, and live in a room next to the classroom, equipped as for a living room. In addition, there were endless inspections of higher authorities. Those who aspired to give themselves to children and work as much as possible, trying to bring creativity to the classes, ran out of steam and burned out after several years of work.

Conclusion

The role of the Ural zemstvos is difficult to overestimate. Thanks to their initiative, institutions responsible for public education appeared and then expanded in the region. Art exhibitions, museums, drama clubs, reading houses, people's houses, public readings - this is an incomplete list of events that zemstvos promoted among the people. Local governments engaged people into the life of the country, in its political and public spheres. All these activities contributed to the aesthetic formation and refinement of the population.

References

- Adukova, T.Y. (2004). Folk costume in the urban environment of the Urals (early 20th century). Historical readings: materials of the scientific conference of the Center for Historical and Cultural Heritage of the city of Chelyabinsk. Volume 7-8. (pp. 205-212). Chelyabinsk, Center for Historical and Cultural Heritage.

- Allied thought. (1918). Chelyabinsk Zemstvo, 8.

- Bogdanovsky, V.I. (2000). Chelyabinsk Region in photographs 1900–1920. Chelyabinsk, Stone Belt.

- Ufa Historical Archive (1915). Historical and statistical tables of the Ufa zemstvos. To the 40th anniversary of the existence of the zemstvos of the Ufa province. 1875-1914 Ufa: Provincial Printing House.

- Minenko, N.A., Apkarimova, E.Y., Golikova, S.V. (2006). Daily life of the Ural city in the XVIII - at the beginning of the XX century. Moscow: Science.

- NMRB, (2016). National Museum of the Republic of Bashkortostan. Documentary Fund (NM. RB. DF).

- Orenburg Zemstvo, (1916). Orenburg Zemsky business, 16, 16.

- Perm government, (1915). Reports on public education in 1913-1915. Perm: Printing house of the Perm provincial government.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

29 March 2019

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-057-0

Publisher

Future Academy

Volume

58

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-2787

Subjects

Sociolinguistics, linguistics, semantics, discourse analysis, science, technology, society

Cite this article as:

Suvorova, A., Semenchenko, I., & Serebryakova, A. (2019). Development Of National Education By Local Authorities In Ural. In D. K. Bataev (Ed.), Social and Cultural Transformations in the Context of Modern Globalism, vol 58. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 827-835). Future Academy. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2019.03.02.95