Abstract

Due to increasing pressures on an uncertain, changing, complex and interdependent world, academia and business have attempted to identify theoretical and applicative solutions to help organizations cope with challenges and provide them with a competitive advantage. So, the concept of organizational learning has been extended from business to schools, as organizations that are traditionally linked to learning and knowledge and could be extended to the existing school sports clubs in Romania. Taking into consideration their peculiar typology within the pre-university system, being also schools and sports structures, the present theoretical article provides a combined possible approach to these organizations, using the benchmarking concept and model altogether with the learning organization concept and model. The benefits of the combined implementation of the two approaches are highlighted, the professional network in which the school sports clubs operate creating the premises of a learning community that uses benchmarking to measure, compare and improve performances – at individual athlete level, at sports team level and at organizational level. The approach is in line with that of the OECD, which proposes rethinking the school as a learning organization so that it can cope with an ever-changing external environment and facilitate organizational efficiency, but it is adapted to the specificities of the school sports clubs.

Keywords: School sports clubsbenchmarkingorganizational learninglearning organizationsprofessional network

Introduction

In a changing, complex, interdependent and uncertain world, characterised by the emergence and development of new information technologies and the growth of inter-relational processes, throughout the transition period between the 20th and the 21st century, there has been increasing pressure to identify theoretical and applicative solutions to help organizations cope with challenges and provide them with a competitive advantage, pressure from both the business environment and other wider environments - health, environmental protection, administration and education. Since education is no longer a luxury but a necessity, this increasing pressures was also felt at school organizations level, organizations which in the same time needed to reach their core objectives, to meet the expectations of different stakeholders (students and parents, educational and administrative authorities, employers) and to provide (develop) that environment capable of leading and sustaining each individual on the path of becoming an adult responsible person, ready for the demands of the labour market.

Nowadays this pressure is even stronger, especially due to scarcity of financial resources and school organizations were, and still are, subject of two types of approaches – a first category is represented by various analyses aimed at measuring their efficiency and second category is represented by various re-conceptualisation models, as theoretical attempts (of the academic and business environment) aimed at supporting them not only to the improvement of the educational services, but also to the growth/development of the working environment (so that it adapts more easily to the challenges, responds more quickly to different situations/problems and becomes more efficient).

In past decade one of the most influential projects which evaluates, on a regular basis, the quality, the equity and the efficiency of school systems it proved to be PISA (the OECD Programme for International Student Assessment) and one of the most challenging models proposed for school’s re-conceptualisation was that of “learning organizations”; However, while PISA evaluation reveals the 15-year-old students performances in mathematics, science and reading, and cannot be applied for the evaluation of the efficiency in performance sports education, the adoption of the concept and models of school as a learning organization knew a gradual evolution, irrespective of the type of educational services provided and regardless the organizational size and can, therefore, be applied to school organizations providing performance sports education services; thus, the latest ideal model for reconceptualising the school as a learning organization, proposed by the OECD (2017), could be tailored to the specifics of sport education.

Problem Statement

In Romania case, performance sports education at pre-university level is organized in schools with integrated sports program or with additional sports program (“niche” organizations), the latter being known as school sports clubs and representing a peculiar typology within the pre-university system - being in the same time school organizations and sports structures, registered both in the school networks at the local (county) administrative level and also in the sports registers administered by the line ministries, which creates a pattern of administrative communication different from other types of schools.

Although it would have been expected that this kind of subordination and relationship would produce beneficial effects on school sports clubs (which counts in Romania only 130 organizations of this type, 66 of them having legal personality and 64 of them being structures attached to other educational units), in 2013,

Therefore, the separation of the competencies of the line ministries (the evolution of the last 10 years being from an integrating ministry, which juxtaposes education and sport, to two ministries with distinct attributions), multiplied the necessary organizational relationships and generated “fractures” at the level of the communication channels network and the lack of a strategy in the field of sport and physical education deprives a long-term vision and a systematic approach to the development of priority directions, with effects also on school sports clubs.

Considering the General Decentralisation Strategy (Government Decision No. 229/2017), through which the local public administration authorities will exercise new competences, including in the field of youth and sport (on extracurricular education which is achieved by palaces, clubs and school sports clubs, under the circumstances the latter are not nominated in educational legislation as institutions providing extra-curricular education), it follows that new cross-communication lines must be developed between these authorities and those which school sports clubs already interacts, together with the revitalisation of communication channels between Ministry of Education and the Ministry of Sport, County School Inspectorates and County sports associations.

Much more, although school sports clubs have institutional relationships with two overhead entities at central level, namely the Ministry of Education and the Ministry of Sport, their functioning and funding are carried out by the Ministry of Education; that is why these organizations have the legal obligation to implement the quality assurance mechanisms in education stipulated by national quality legislation - to carry out an annual self-evaluation process and to publicly report the results (based on 43 performance indicators), to be externally evaluated every 5 years and to make public the quality level of the services provided (based on same 43 performance indicators). Furthermore, although the Romanian legislation on quality assurance in education has been in place since 2005, only 10 school sports clubs have been evaluated so far (between 2015 and 2017) and the results of these external evaluation activities reveal, on the one hand, insufficient concern of the internal management for the application of the self-evaluation mechanisms (in place for all schools in the pre-university system), and on the other hand, inadequacy of the instruments used in the external evaluation for these “niche” entities, which have a pronounced specificity regarding the “inputs” and the “outcomes”. That is why, at the level of the 10 externally assessed school sports clubs, the following paradoxical situations have been recorded:

50% of them do not meet the minimum requirements to at least one of the 43 national performance indicators, although they report sports performances;

50% of them are registered with an efficiency index below 1 (means the achieved results were below expectations), although they have the necessary resources and report high level results;

over 60% of them have “zero” results (non-results) in at least one sports discipline, although they have legitimate sports students and qualified staff.

Since September 2018, it is scheduled the evaluation of another 20 school sports clubs, and around 2020, the evaluation process will end for all school sports clubs with legal personality; the situation, as currently presented, is unsatisfactory, at risk in the context of completing the evaluation of all these units in the same formula as before. In addition, although the number of school sports clubs is insignificant compared to the number of schools from the 2017 pre-university network (6413 independent schools, which may have one or more locations) and even though school sports clubs take part in the same sports competitions, there is no sharing and exchange of best practice between them. That is why the National Strategy for Sport (The Ministry of Youth and Sport, 2016, pp. 19-20), document still under debate and revision, specify as directions of future action “the creation of a collaborative network between coaches from different sporting disciplines for the dissemination of knowledge and pooling of experiences” (for improving human resources directly involved in performance sports) and “the support for school sports clubs […], so that they regain, alongside with private sports clubs, the status of sports performance nursery” (for developing the identification and selection system for young talents).

Therefore, the reduced number of school sports clubs, their “niche” status, the lack of government visibility caused by the weak relations between the central administration institutions with attributions in the field, can lead to measures not in favour of the Romanian sport.

Research Questions

Taking into consideration the problems that school sports clubs are facing, there are three research questions that are underpinning the present approach to them:

How can the results of the 2015-2017 external evaluation of the 10 school sport clubs be used by other similar organizations?

How can the efficiency of the school sports clubs, without financial infusion, be increased?

How can fractures in communication with school sports clubs be overpassed?

Purpose of the Study

In this context, the present paperwork aims to provide a theoretical joint approach to school sports clubs, proposing three possible directions of intervention in the school sports clubs area, in line with the 2015 findings of the Romanian Court of Accounts, with the 2016 Romanian National Strategy for Sport and with the 2017 OECD’s proposal for scholars, educators, policy makers, parents and others stakeholders to develop a model of school as learning organisation:

the first one targets the creation of a pool of positive and negative results found during the external evaluation of school sports clubs’ processes, so that they will became “benchmarks” against which to report and compare, setting up a starting point for a professional sharing of experiences between these organisations;

the second one targets the development of a tailored approach to school sports clubs as learning organisations, so that they could increase their capacity to change and adapt in an increasingly competitive environment;

the third one targets the creation of a communication network which cope the new systemic realities that are predominant in Romanian society and will include all institutions linked with school sports clubs, so that fractures in the communication can be overpassed.

This way, what is being pursued is to support the improvement of the educational services they provide and the growth/development of their working environment.

Research Methods

This paperwork is based on desk research (literature review) in three areas – the benchmarking concept and process, the learning organizations and the communication process - together with analysis of data previously collected (between 2015-2017) in the external evaluation process of 10 school sports clubs (these were nominated for evaluation by the county school inspectorates from seven counties – Alba, Arad, Bucharest, Dolj, Ilfov and Teleorman – taking into consideration two aspects: their status as school units and the fact that they never went through a regular external evaluation process).

Regarding the external evaluation of the 10 school sports clubs, the following should be mentioned: (1) till now, at national level, only they were included in the evaluation process, but by 2020 it is foreseen to evaluate all the other 56 organizations with legal personality; (2) the evaluation of the quality of the educational services provided by them as schools is done by The Romanian Agency for Quality Assurance in Pre-university Education (ARACIP) by reference to 43 performance indicators and to an efficiency index; (3) the 43 performance indicators are defined as instruments to measure the degree of achievement of an activity carried out by an education provider (by reference to standards) and the efficiency index is defined as the ratio between an aggregate indicator related to the “results” and an aggregate indicator reflecting the “resources”, being statistically determined.

Those 10 organizations do not represent a sample of all the 66 school sports clubs with legal personality who are functioning now (nor regarding the geographical spreading, nor regarding the number of sports students enrolled or other criteria), but we will provide a proof of how data collected from all the school sports clubs who went through a regular external evaluation process could be used as a starting point of a benchmarking process within the community they form, in order to build an operational network for sharing experience.

Findings

The constant decrease of public expenditure in education, from 5.76% of total expenditures in 2009, to 3.76% of total expenditures in 2017, has decisively determined the direction of research, trying to identify solutions that do not include an infusion of financial capital.

From disparate outcomes of school sport clubs’ external evaluations to a pool of positive and negative results against which to report and compare

Because most times it is quite difficult to innovate and do things completely different from the competitors, the benchmarking process, initially practiced in the US among organizations and managers in the private business sector, had in last decades an international expansion, being used now on a large scale at both private and public sector organizations as a learning method and also as a managerial practice. Starting from the meaning of the English word ‘benchmark’ (‘milestone’/ ‘landmark’) and from the business definition of the process: “a measurement of the quality of an organization’s policies, products, programs, strategies etc. and their comparison with standard measurements or similar measurements of its peers” (Business Dictionary, 2018), the concept consists of a systematic and permanent process of measuring and comparing the work processes of an organization with those of another one recognised as being the best, in order to increase performances (Spendolini, 2006).

But for benchmarking to be effective it should be placed inside of a network; this way, the identification of best practices in different areas of organizational interest, followed by a process of recording and dissemination of what is found, will became part of a broader performance improvement strategy of the network (Jupp, 2010).

Taking into consideration the reduced number of school sports clubs and their “niche” status, they are the ideal platform for a network. But till now, only few insides from their organizational processes are available, without having the certainty that they represent a best practice; however, the results of the external evaluation developed between 2015 and 2017 were divided into two categories - positive results when a certain indicator has been rated as “good“ or “very good“ and negative results when a certain indicator has been rated as “unsatisfactory“ (Table

This way, the results of the 2015-2017 external evaluation of the 10 school sport clubs can be used by other similar organizations and the need to learn from the experience of others could be nurtured, appreciating that this may be the starting point to setting up a professional network for sharing experience, a learning community that uses these results and those to come as “milestones” (“benchmarks”) against which to report and compare.

From “learning organization” to school sport clubs as a “learning organization”

The challenges of postmodern society have led to new organizational models, as theoretical attempts (of the academic and business environment) to give solutions to the need for companies to adapt and survive: (1) “learning organization”, where learning, both individual and collective, and good harmonisation between the individual and the organization, produces benefits to both parties and underpins the achievement of competitive advantage; (2) “relational organization”/ “network organization”, where vertical control and communication relationships are replaced by lateral collaboration and consultation relationships, which leads to greater flexibility and adaptability when problems cannot be broken down and distributed among specialists within a hierarchy; (3) “smart organization”, where the competitive advantage is not obtained from high-quality but ephemeral products, but through a need analysis and the implementation of strategies around core elements – knowledge and service-based activities, where each value creation activity has to be defined as a knowledge-based service.

Among these models, the “learning organization” is the one that gets to be the most challenging since the results of its implementation are only visible on long-term and it is essential to encourage permanent development (continuous learning at all levels - individual, group, organizational). The advantages of implementing the concept and model, according to Sarder (2016), derive from the following: (1) the organization gets always to be supplied with innovative ideas and information (coming from science and technology, the environment, human resources development etc.); (2) learning, as a process of the whole organization, makes innovative ideas and information to be spread and transferred to all (organizational) levels, from the bottom to the top, and transposes them into action; (3) learning not only leads to the improvement of the offered products and/or services, but also to the growth/development of the working environment, which adapts more easily to the challenges, responds more quickly to different situations/problems and becomes more efficient; (4) organizational behaviour changes because of the development of an open and trustworthy environment, changes are perceived as part of the process of improvement and development, and organizational culture becomes one of continuous improvement; (5) the organization is more likely to attract, keep and motivate the best employees.

It is widely accepted that the “learning organization” as a concept and model has gained wide recognition when Peter M. Senge (1990) has published the paper work

From the moment of recognition on a large scale, the model and concept had many approaches from theoreticians and practitioners, some later models trying to provide a more detailed perspective on learning at all levels (individual, team, organizational), as the one proposed by Watkins and Marsick (1996), or on management practices and organizational policies in relation to the definition of the learning strategy, as the one proposed by Goh (1998). In fact, every model of learning organization developed by theoreticians or practitioners could be followed, needing only the development or adaptation of a measurement and evaluation tool, but what needs to be understood is that: (1) transformation and results are not immediate, requiring time and effort at all levels, changes in mentality, commitment from management; (2) there is no final line, but a commitment to continuous transformation (flexibility, adaptation, redefinition due to contact with the external environment) through permanent learning.

Although school is the organization that is traditionally linked to learning and knowledge, however is it a learning organization? It should be, since education is no longer a luxury but a necessity, each school being subjected to enormous pressure to provide that environment capable of leading and sustaining everyone on the path of becoming an adult responsible person. Therefore, not only teaching and learning methods and strategies should be changed, but also school perspectives as a closed, hermetic organization that is self-sufficient, those about the centring of each discipline department only on their own curricular goals, the ones concerning the professional development of the teaching staff only as an attribute of the person, as well as those about disciplinary content as being immutable and non-negotiable. Change is necessary but also mandatory, both for what professional education means and for what sporting performance education means, each person being free to choose the school that offers the safest prospect of professional insertion, or, in the case of school sports clubs, the safest prospect of sporting performance.

Therefore, having as background the models for learning organizations proposed so far, the 2017 OECD’s proposal for scholars, educators, policy makers, parents and others stakeholders is to develop a model of “school as learning organisation” on seven dimension, seen as directions to be followed (OECD, 2017): (1) developing a shared vision centred on the learning of all students, (2) promoting and supporting continuous professional learning for all staff, (3) promoting team learning and collaboration among all staff, (4) establishing a culture of inquiry, exploration and innovation, (5) embedding systems for collecting and exchanging knowledge and learning, (6) learning with and from the external environment and larger system and (7) modelling and growing learning leadership.

Taking into consideration that school sports clubs represent a peculiar typology within the pre-university system – being in the same time school organizations and sports structures – we appreciate that a tailored approach to them is needed, proposing five dimensions as learning organizations to be followed:

promoting and supporting continuous learning - face-to-face and through ICTs, allocating time for collaborative working and collective learning, based on trust and mutual respect;

establishing a culture of investigation and dialog - allowing staff (coaches) to experiment in their practice, without being penalised if the results are not, from the outset, the ones expected and seeing problems and mistakes as opportunities for learning;

promoting and supporting peer learning (for students, professionals and organizations) - from the external environment, having as background the network that could be established between school sports clubs for sharing experience;

embedding systems for collecting and exchanging knowledge and learning - the school development plan being evidence-informed and updated regularly, if necessary;

promoting and supporting a strategic leadership of the organizations - school managers acting as change agents, developing the culture, structures and conditions to facilitate dialogue and collaboration with all interested partners (other school sports clubs, sports federations, parents, the community etc.)

In this way, school sports clubs can use learning at all levels to engage in a transformation journey, becoming adaptable organizations that react and respond quickly to different situations/problems, improve their educational services and enhance outcomes (sports performance of legitimate students) and, ultimately, become more efficient (as long as the results grow and the allocated resources remain the same or are diminished).

From a centralised “double-circuit Y” communication network (bureaucratic) to a “star multichannel” decentralised network (customer-centred)

One of the major objections now in Romania is the bureaucracy, understood in diverse ways, but consisting on overlapping reports holding identical or similar content, or on different communication streams without immediately perceptible and useful feedback to the transmitter. The transmission of data and information by sports education organizations is often perceived (by them) as a formal obligation of unclear utility; the process is disturbed by delays and the transmitted data lack quality and completeness.

The school sports organization's manager must take decisions based on the flow of information received, communicate them to the members of the organization, control their execution, stimulate the cooperation and involvement of members in achieving the objectives, assess the achievement of the results, and report periodically (as action directed towards the outside of the organization). This latter action, reporting, differentiates school sports clubs from other sports structures, because it reveals their specificity and the positioning, in terms of communication, in certain types of networks, due to the existing systemic management levels and the formal organizational relationships set up by the legislation in force.

The school sports clubs currently running in Romania are both sports schools and sport structures, therefore the following aspects can be found:

as a sporting structure, the club must be registered with the Sports Register administered by the competent ministry (Ministry of Youth and Sports) and, in this respect, applies the provisions of Law no. 69/2000 (Law on Physical Education and Sport); as an educational organization, the club operates on the basis of Law no. 1/2011 (Law on National Education) and is an educational institution;

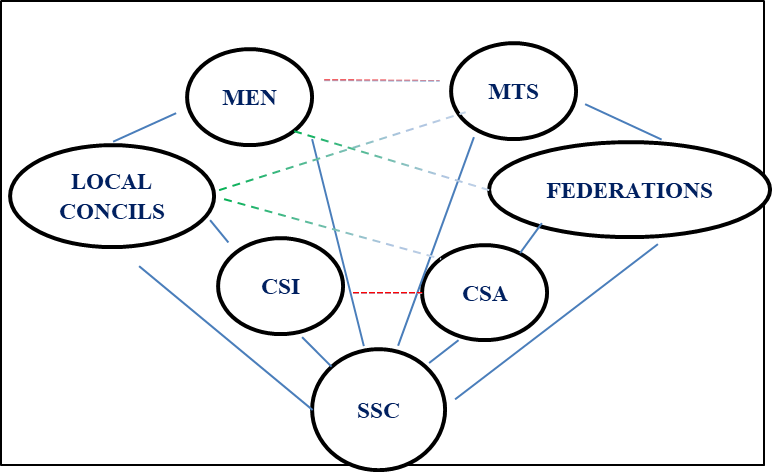

considering the three-level management pyramid, these organisations are, at top management level, linked to two ministries (of education and sport), so they subscribe to two communication channels; at middle management level, these organizations have reporting obligations to School Inspectorates (educational line) and Local Councils (administrative line) and interacts in ascending line with the County Sports Directorates and on the oblique line with the County Associations on Sport branches; horizontal communication is done with local and national sports structures, as well as sports clubs in sports.

Organizational management literature has taken on and nuanced specific concepts in communication science, creating correlations between organizational structures and information systems. In the 1970s, organizational communication was defined as “a process of creating and exchanging messages within a network of interdependent relationships to cope with environmental uncertainty” (Goldhaber, 1986, p. 17). For organizational communication, it was important to know how the communication process works, who communicates with whom, which are central or marginal, within two types of networks: centralising (with information that goes to the centre and is suitable for relative activities simple to execute) and decentralising (in which information sharing does not have a matrix required, more suitable for complex activities).

Centralised networks are specific to hierarchical relationships that involve levels of overriding and subordination management. Their specificity is the authoritarian style of management, and communications can only be effective only subject to the requirements of formalisation required (standard format, template etc.), depending on the databases in which this information will be aggregated. However, uniform decisions are made, responsibility is specified, and functions of coordination and control are well represented. Unlike these, within decentralised networks, group members are equal in hierarchy level, participatory management is facilitated, and communication is not only effective (result-oriented) but also efficient (maximising results with minimal resources); however, power and authority are scattered, and failure to specify responsibility and the exercise of coordination may create problems for different organizations. Decentralised networks comprise “circle“ and “chain“ communication models, and centralised networks include “Y“ and “star“ communication models (Nicolescu & Verboncu, 2008). However, a new, comprehensive network model emerges, the “multichannel star” network where each member can communicate freely and openly, without discrimination, the management style is permissive, using all the resources of others to achieve their goals.

Shaping the communication of the school sports clubs, based on the analysis of the current hierarchical relationships, is illustrative of the institutional evolution at the central level, with an impact on the functioning of the institutions at the base. The separation of the competences of the line ministries (the evolution of the last 10 years was from an integrating ministry, which juxtaposes education and sport, to two ministries with distinct attributions, aspect that multiply the organizational relations and the network of communication channels) generated more “fractures“; the “Y“ double-circuit model has two fractures inside the communication circuit, one on the first level, between the ministries, the second on the local county level, between the school inspectorates and the sports associations (see, Figure

Therefore, the communication network in which school sports clubs are included should undergo a mandatory mutation, an evolution from the “Y“ double-circuit model to the “multi-channel star“ model, customer-centred, and as an immediate measure it would be necessary to develop inter-institutional protocols/partnerships on collaborations and joint activities responding to the need for sporting performance instrumented for educational purposes;

Conclusion

Research findings highlighted three main issues:

the creation of a pool of positive and negative results found during the external evaluation of school sports clubs’ processes could became “benchmarks” against which other similar organizations to report and compare, setting up a starting point for the professional sharing of experiences between these organisations;

(b) a tailored approach to school sports clubs as learning organisations, could increase their capacity to change and adapt in an increasingly competitive environment, improve their educational services and enhance their outcomes; becoming more efficient;

(c) the communication network in which school sports clubs are included should undergo a mandatory mutation, an evolution from the “Y“ double-circuit model to the “multi-channel star“ model, copping the new systemic realities that are predominant in Romanian society and including all institutions linked with them, so that fractures in the communication can be overpassed.

References

- Business Dictionary. (2018). Benchmarking (Definition). Retrieved from http://www.businessdictionary.com/definition/benchmarking.html

- Curtea de Conturi România. (2013). Sinteza raport de audit al performanței privind eficiența utilizării resurselor alocate de la bugetul statului pentru îndeplinirea obiectivelor propuse de către Ministerul Tineretului și Sportului, Comitetul Olimpic și Sportiv Român și federațiile sportive naționale (Summary of the performance audit report on the efficiency of using the resources allocated from the state budget for the achievement of objectives proposed by the Ministry of Youth and Sports, Romanian Olympic and Sport Committee and national sports federations). Retrieved from https://sportlogic.files.wordpress.com/2016/02/sinteza-raport-ap-cosr.pdf

- Goh, S. C. (1998). Towards a learning organisation: The strategic building blocks. SAM Advanced Management Journal, 63(2), 15-22.

- Goldhaber , Gerald M 1990 , Organizational communication ,

- Goldhaber , Gerald M 1990 , Organizational communication ,

- Goldhaber , Gerald M 1990 , Organizational communication ,

- Goldhaber, G. M. (1986). Organizational communication (5th ed.). Michigan: Brown & Benchmark.

- Jupp, V. (2010). Dicționar al metodelor de cercetare socială. Iași: Polirom.

- Mihăilă, C. V. (2017). Useful methods of learning and development for educational organizations from the sports field: Benchmarking/ “good” and “bad” practices. Discobolul – Physical Education, Sport and Kinetotherapy Journal, XIII, 4(50), 43-49.

- Ministerul Tineretului și Sportului. (2016). Strategia națională pentru sport. Retrieved from http://mts.ro/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/Strategia-nationala-pentru-SPORT-v2016-v2.pdf

- Nicolescu, O., & Verboncu, I. (2008). Fundamentele managementului organizației. București: Editura Universitară.

- OECD. (2017). What makes a school a learning organisation? A guide for policy makers, school leaders and teachers. Retrieved from http://www.oecd.org/education/school/school-learning-organisation.pdf

- Sarder, R. (2016). Building an innovative learning organization: A framework to build a smarter workforce, adapt to change and drive growth. Wiley.

- Senge, P. M. (1990). The fifth discipline: The art and practice of the learning organization. Michigan: Doubleday/Currency.

- Spendolini, M. J. (2006). The benchmarking book (2nd ed.). New York, NY: AMACOM.

- Watkins, K. E., & Marsick, V. J. (1996). In action: Creating the learning organization. Alexandria, VA: ASTD Pres.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

16 February 2019

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-054-9

Publisher

Future Academy

Volume

55

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-752

Subjects

Sports, sport science, physical education

Cite this article as:

Mihăilă, C., & Paraschiva, G. A. (2019). An Approach To School Sports Clubs As Learning Organizations. In V. Grigore, M. Stănescu, M. Stoicescu, & L. Popescu (Eds.), Education and Sports Science in the 21st Century, vol 55. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 453-464). Future Academy. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2019.02.57