Abstract

Fundamental approaches to financing the education sector depend on economic and political management models applied in countries. Economic conditions have a significant impact on the education system. The public sector of education gradually changes according to the principle of self-sufficiency. At the same time, the development of a market economy, taking into account the tendencies of the formation of a post-industrial society, leads to an increase in the need for education and, above all, in higher education in the areas of high technology. Both education and science require significant investment, not providing a quick return. This part of the budget is costly and accounts for a fairly large share of GDP. How do countries with different supply of natural resources come out of this difficult situation? What trends can be traced in the financing of education? The objective of the paper is a retrospective analysis of the financing of education (in % of GDP) in the countries of the world, depending on what proportion of GDP is made up of natural resources. In authors’ opinion, it determines a strategy of long-term investments in human resources with varying degree of availability of natural resources. The authors use comparative analysis of data from open sources of the World Bank. Presenting free access to statistical information about development indicators around the world, the World Bank makes it possible to conduct such retrospective studies.

Keywords: Financing of educationnatural sources

Introduction

The problem of financing education in most countries is exacerbated by the continuing decline in the global economy. At the same time, despite the reduction in the total amount of public funding, higher education in the EU countries is funded by public expenditure by almost 80%, the rest is unevenly distributed between investments from non-profit organizations (about 5%) and more than 12% the quality of tuition fees by the students themselves (their families) (Modernization of Higher Education, 2011).

The lack of funding for education during the recession is observed in many countries; it is also noted that the low proportion of people with higher education is typical for most developing and less industrialized countries (ibid.).

In education policy, there is a growing connection with the policy on employment, employment. In developed countries, the search for new ways of financing education is associated with changes in the social structure of society in favour of the middle class. In general, the solution of problems in the field of financing of education is influenced by such socio-economic processes as the actual development of the education financing system; financing of education in order to invest in human resources; development of the education payment system (Chepyzhova, 2012; Rostovskiy, 2012). Thus, in developed countries, much attention is paid to the development of the education system throughout life. Models of continuing education are built on the notion of equity and equality in obtaining education; increase in the share of education at work in the system of continuing education. In general, there is an understanding that education is the source of the nation’s well-being.

World Bank development has identified new approaches to funding education in the US, Scotland, Australia, New Zealand, South Africa. Reforming activities and funding in the field of education is being implemented in Spain, the Netherlands, Sweden, and Germany (Hoffman, 2000; Materialy sayta banka dannykh Vsemirnogo Banka, 2018).

Problem Statement

Fundamental approaches to financing the education sector depend on economic and political management models applied in countries. Economic conditions have a significant impact on the education system. The public sector of education is gradually being translated into the principle of self-sufficiency. At the same time, the development of a market economy, taking into account the tendencies of the formation of a post-industrial society, leads to an increase in the need for education and, above all, in higher education in the areas of high technology.

In recent years, attempts have been made in the world to redistribute the financial burden on education, which implies a change in the share of participation of each of the sources of financing. Developed European countries and the United States are revising the system of financing education. For example, in higher education, a redistribution of the costs of higher education between students, parents and taxpayers is proposed (Sumarokova, 2014). In addition, in the United States and the United Kingdom, another important source of financial resources for private universities is being more actively involved in financing education: individual and institutional philanthropy.

In Russia, this process is characterized by a simultaneous reduction in the state order for the training of specialists, a drop in the demand of businesses and individuals for paid educational services (Rossiyskiy statisticheskiy ezhegodnik, 2017). At the same time, the management of higher education by the state increasingly focuses on financial levers, rather than on administrative ones, encourages higher educational institutions to become more actively involved in market relations.

Research Questions

Mau (2002), defining the ability of the state to concentrate resources on the development of education as the most important factor in accelerating social and economic development in the post-industrial era, believes that state participation in this business plays a significant role, since in a relatively backward country the possibilities for private investment in education remain rather limited.

Glazyev (2005) maintains the same opinion, arguing that education in all countries with a developed market economy develops as a public good and is financed to the decisive degree by the state.

International experience shows that if public spending on science does not exceed 2% of GDP, society suffers because of slow scientific and technological progress. And if the cost of education does not exceed 5% of GDP, the nation is doomed to intellectual degradation (Khodzhabekyan, 2005) Just as in its time industrialization required universal secondary education, the “knowledge economy” requires a transition to a universal, higher education accessible to everyone. Education and science should become the priority spheres of state financial investments. But both education and science require significant investment, not providing a quick return. This part of the budget is costly and accounts for a fairly large share of GDP.

How do countries with different resources of natural resources come out of this difficult situation? What trends can be traced in the financing of education?

Purpose of the Study

The task of the study is a retrospective analysis of the financing of education (in% of GDP) in the countries of the world, depending on what proportion of GDP is made up of natural resources, that is, long-term investments in human resources with varying degrees of availability of natural resources.

Research Methods

This study used statistical analysis, comparative qualitative and quantitative analysis.

Findings

The World Bank, being an international organization with 189-member countries, is a reliable source of information. By presenting free access to statistical information (Materialy sayta banka dannykh Vsemirnogo Banka, 2018) about development indicators around the world, the World Bank makes it possible to conduct retrospective studies.

Statistics on the financing of education (in% of GDP) are available since 1970, but data for the countries of the Russian Federation and other countries of the post-Soviet space are available only since 1993. On the other hand, the range of retrospective research is limited to 2014, as the data for 2015-2016 are not yet fully complete. Another limitation is the failure to provide a number of countries, mostly island and dwarf States, with statistical information that allows the inclusion of these countries’ data in the study.

Retrospective consideration allows us to divide countries into groups according to the average 22-year share in the GDP structure of natural resources. The full list of countries chosen for research includes 115 countries.

The first group comprised 14 countries with a share of natural resources of 20-40% of GDP:

Republic of the Congo, Angola, Oman, Gabon, Uzbekistan, Qatar, Azerbaijan, Bahrain, Turkmenistan, Brunei, Libya, Trinidad and Tobago, Nigeria, Kazakhstan.

The second group includes countries with a share of natural resources in the structure of GDP of 10-20% includes 20 countries, including the Russian Federation:

Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, Equatorial Guinea, Yemen, Iraq, Papua New Guinea, Bhutan, Algeria, Burundi, Guinea, Ethiopia, Venezuela, Uganda, Iran, Syria, Russia, Egypt, the United Arab Emirates, Liberia, Sierra Leone.

The third group consists of 27 countries with a share of 5-10% of natural resources in the structure of GDP:

Mauritania, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Vietnam, Somalia, Ecuador, Solomon Islands, Suriname, Indonesia, Togo, Norway, Bolivia, Mongolia, Malaysia, Rwanda, Ghana, Laos, Malawi, Chad, Zambia, Cameroon, Chile, Nepal, Paraguay, Guyana, Niger, Eritrea, Peru.

The fourth group unites 32 countries with less than 5% of natural resources in the GDP structure, but more than 2%, which is the world average:

Colombia, Sudan, Tunisia, Mexico, China, Lesotho, Ukraine, Kenya, Kyrgyzstan, Argentina, Nicaragua, Myanmar, Guinea-Bissau, Albania, Cambodia, Gambia, India, Canada, Romania, Pakistan, Mali, Bangladesh, Jamaica, Australia, New Caledonia, Guatemala, Burkina Faso, Honduras, South Africa, Namibia, Sao Tome and Principe.

The fifth group is made up of 22 countries that have more than the world average, but less than 1% of natural resources in the GDP structure:

Cote d'Ivoire, Haiti, Thailand, Comoros, Brazil, Swaziland, Zimbabwe, Afghanistan, Croatia, Macedonia, United Kingdom, Salvador, Belarus, Botswana, Netherlands, Costa Rica, Philippines, United States of America, Latvia, Belize, Djibouti, Sri Lanka.

The sixth group is the most heterogeneous and numerous (64 states) and unites countries with less than 1% of natural resources in the GDP structure:

The Dominican Republic, Cuba, Armenia, Estonia, Uruguay, Mozambique, Tanzania, New Zealand, Tajikistan, Denmark, Samoa, Morocco, Benin, Barbados, Bulgaria, Poland, Slovakia, Madagascar, Hungary, Georgia, Fiji, Jordan, Lithuania, Cabo Verde, Israel, Senegal, Turkey, Slovenia, Moldova, Ireland, Austria, Dominica, Italy, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, Czech Republic, Germany, Greece, Seychelles, Sweden, Finland, Spain, Maldives, Bahamas, Saint Lucia, Tonga, Cyprus, South Korea, France, Luxembourg, Portugal, Micronesia, Switzerland, Japan, Central African Republic, Mauritius, Panama, Hong Kong, French Polynesia, Singapore, Belgium, Iceland, Kiribati, Lebanon, Vanuatu.

(List of countries not included in the study:

American Samoa, Andorra, Antigua and Barbuda, Aruba, Bermuda, Bosnia and Herzegovina, British Virgin Islands, Cayman Islands, Channel Islands, Curaçao, Faeroe Islands, Gibraltar, Greenland, Grenada, Guam, Isle of Man, North Korea, Kosovo, Liechtenstein, Macao, Malta, Marshall Islands, Monaco, Montenegro, Nauru, Northern Mariana Islands, Palau, Puerto Rico, San Marino, Serbia, St. Martin - Dutch part, South Sudan, Saint Kitts and Nevis, Saint Martin - the French part, East Timor, Turks and Caicos Islands, Tuvalu, Virgin Islands (USA), the West Bank and Gaza).

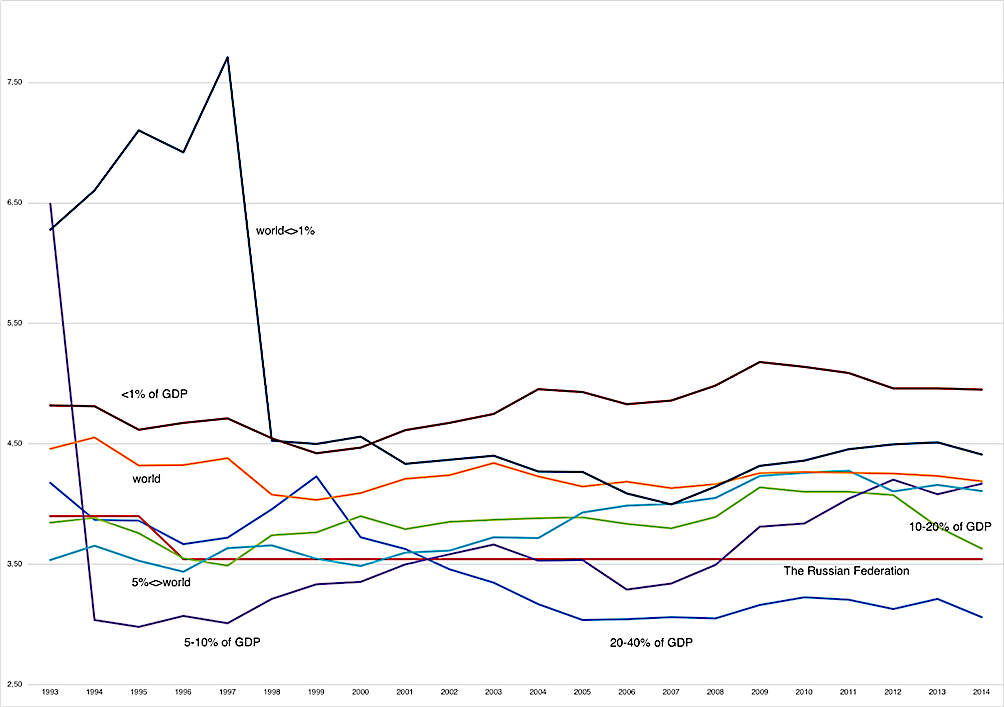

The figure below (Figure

The chart shows that the countries having average reserve of natural resources:

less than 1% reduced the financing of education slightly under the influence of the 1998 crisis, but quickly compensated for the drop and the share of education financing in the GDP structure shows stable growth.

from 1 to 2% of GDP, the most (almost 2 times) decreased funding for education under the influence of the 1998 crisis and demonstrate further stagnation.

from 2 to 5% - show insignificant but stable growth, as well as countries 5-10%.

10-20% slightly reduced financing before the crises of 1998 and 2008, but compensated for the decline for 3-4 years.

20-40% increased funding by 1999, but then sharply reduced funding and did not return to previous borders.

The world as a whole demonstrates a slight decrease in funding after the 1998 crisis and subsequent stable values.

Since 1996 the Russian Federation has not changed the share of GDP attributable to education.

Let us put the average data by groups in Table

Average funding for 1993-2014 will show the average funding for countries in each group as a percentage of GDP; the average deviation of 1993-2014 is the spread in the values of financing by years; the average deviation in the group countries is the heterogeneity of the financing of the education of the countries within the group, the average share of natural resources is the average value of the share of natural resources in GDP.

From this table, an inverse correlation between the share of natural resources in the GDP structure and long-term investment in human resources (financing of education) is evident.

The average deviation shows that the least amount of funding for the formation of the country with a share of natural resources of 10-20% in the structure of GDP, including Russia, most of all in the countries with a share of natural resources of 5-10% and 1-2% in the structure of GDP. These groups (5-10% and 1-2%) were the most heterogeneous in individual countries’ behavior.

The average funding for education in the world is 4.24%, for countries with a share of natural resources in GDP below the average, this index is 4.79%, for those with higher share of resources the indicator is 3.63.

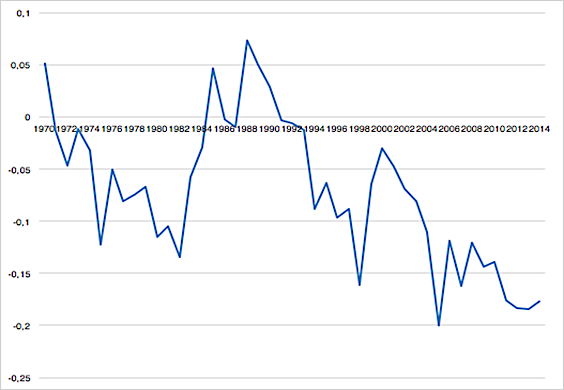

Figure

Conclusion

The greatest mutual influence on the labour market is provided by secondary and higher vocational education. The tendencies in the financing of education are most evident in this sector of education and are most influenced by the training of future specialists. As for the development of human capital, this is relevant for developed countries. For countries rich in natural resources, vocational education is of the greatest importance, personal development and education are given less attention for this purpose. Therefore, we consider higher education, but this can be extended to other forms of education.

The analysis of the degree of state participation in the financing of education on the example of the above-mentioned countries allows us to sum up certain results:

financing of education has alternatives, conditioned by the development of both the society and the education system as a public institution;

there are significant restrictions on the policy of income diversification, which depend on the level of industrial development of the country, the features of historical, cultural and social development;

Higher education faces a deterioration in the financial position of most institutions, especially to the extent that they depend on government funding (Kharitonov, Utyashova, 2017; Abankina, Vinarik, Filatova, 2016; Avvakumova, 2015).

Although for our country there is a tendency for low financing of education by the state, in the context of the financial crisis, Russia, like the OECD and EU countries, is gradually introducing expertly approved mechanisms for regulating state funds aimed at optimizing the budget expenditures of higher education. The application of various mechanisms for regulating financial resources in higher education has a broader practical application in foreign countries, thanks to well-established and reliable tools for attracting non-state funds, as well as funds and sources of other non-state institutions. In Russia, this process is extremely slow, and while the main additional source of higher education in Russia is the expansion of paid education.

One of the ways out in this situation can be the change in the policy of distribution of financial resources in the sphere of higher education in a shrinking market, namely, the revision of the proportion of financial support by the state to higher education institutions and regional universities in favor of the latter.

Acknowledgments

The present research is conducted in compliance with the State Assignment of the Institute for Strategy of Education Development of the Russian Academy of Education within the project 27.8520.2017/BCh.

References

- Avvakumova, A.D. (2015). Puti sovershenstvovaniya sistemy finansirovaniya obrazovaniya. [The ways of education financing system improvement] Fundamentalnye issledovaniya, 6, 91-94. [in Rus.]

- Abankina, I.V., Vinarik, V.A., & Filatova, L.M. (2016). Gosudarstvennaya politika finansirovaniya sektora vyshego obrazovaniya v usloviyah byudzhetnyh ogranichenii [State policy of the higher education sector financing under the conditions of a budgetary organization] Zhurnal NEA, 3(31), 111–143. [in Rus.]

- Chepyzhova, O.K. (2012). Gosudarstvennoe finansirovanie vysshego obrazovaniya: sovremennye tendentsii [State financing of higher education: modern tendencies], Vestnik MGUPI, 39, 201-210. [in Rus.]

- Glazyev, S.Yu. (2005). Ocherednoy “klon” pravitel'stvennykh rynochnykh fundamentalistov [o “Programme sotsial'no-ekonomicheskogo razvitiya Rossiyskoy Federatsii na srednesrochnuyu perspektivu (2005-2008 gg.)”] [Another “clone” of the government market fundamentalists (upon the “Programme on social – economic development of the Russian Federation on the middle-term prospective (2005-2008))”], Rossiyskiy ekonomicheskiy zhurnal, 2, 9. [in Rus.]

- Hoffman, H.G., (2000). Novye formy finansirovaniya, garantiruyuschiye ravnoye obrazovanie dlya vsekh, i razvitie sistemy platnogo obrazovaniya. Nekotorye prakticheskiye primery zapadnoevropeyskikh stran, [New forms of financing guaranteeing equal education for everyone and paid education system development. Practice of certain West-European countries], Universitetskoe upravlenie, 4(15), 35–42. Retrieved from: http://ecsocman.hse.ru/univman/msg/145206.html.

- Kharitonov, D.Ya., & Utyashova, O.V. (2017). Finansirovanie sistemy obrazovzniya [Education system financing] Daidzhest-Finansy, 7(151), 41-45. [in Rus.]

- Khodzhabekyan, V. (2005). Ekonomicheskaya bezopasnost' strany [National economic security], Obshchestvo i ekonomika, 1, 151.

- Mau, V.A. (2002). Postkommunisticheskaya Rossiya v postindustrial'nom mire: problemy dogonyayushchego razvitiya [Post-communist Russia in post-industrial world: problems of catching-up development], Voprosy ekonomiki, 7, 19. [in Rus.]

- Materialy sayta banka dannykh Vsemirnogo Banka [World Bank database materials] (2018). Retrieved from: data.worldbank.org

- Modernization of Higher Education in Europe: funding and Social Dimension. Education, Audiovisual and Culture Agency. (2011). Ed.by A. Delhaxhe. Brussels, Eurydice.

- Rossiyskiy statisticheskiy ezhegodnik [Russian statistical yearbook] (2017). Moscow, Rosstat [in Rus.]

- Rostovskiy, R.V. (2012). Gosudarstvennoe finansirovanie sistemy vysshego obrazovaniya [State financing of the higher education system], Ekonomika I Pravo, Vyp. 2. [in Rus.]

- Sumarokova, E.V. (2014). Finansirovanie vysshego obrazovaniya: primery uspeshnykh resheniy, [Higher education financing: examples of efficient decisions] Byudzhet.ru. Retrieved from: http://bujet.ru/article/263901.php. [in Rus.]

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

28 February 2019

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-055-6

Publisher

Future Academy

Volume

56

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-719

Subjects

Pedagogy, education, psychology, linguistics, social sciences

Cite this article as:

Elkina, I. M., & Bebenina, E. V. (2019). Global Tendencies Of Education Financing For Countries With Different Natural Resources Supply. In S. Ivanova, & I. Elkina (Eds.), Cognitive - Social, and Behavioural Sciences - icCSBs 2018, vol 56. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 17-24). Future Academy. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2019.02.02.3