Abstract

Puberty is a significant element of sex education in the European as well as global context. Children need to be prepared for puberty in time and in an appropriate manner; this should include all related associations and contexts. Timely readiness for puberty means that children have the required knowledge before its onset – during pre-puberty when they are in primary school. The objective of the present study is to identify and describe the level of knowledge about puberty among primary school pupils. We presented the partial results in the context of the Czech Republic, Spain and China. An achievement test was used to determine the knowledge about puberty among primary school pupils. The level of knowledge about puberty was tested by means of 9 items with open-ended answers. The content of the test items focused on the following: concept of puberty; definition of puberty; puberty age range; knowledge about physical changes in boys and girls; knowledge about other changes that puberty induces; significance of puberty in human life.

Keywords: Pubertypupilsknowledgetestingresults

Introduction

Puberty is a significant element of sex education in an international context (Comprehensive sexuality education, IPPF; Standards for Sexuality Education in Europe, 2010) and represents an important aspect in comprehensive education of children. A number of countries not only from Europe are accredited members of the International Planned Parenthood Federation (IPPF), which defines the context of human rights and is active in the area of sexual and reproductive health. The IPPF defines sexual rights, supports the right to freedom and personal safety, and cooperates with other entities to support efforts that introduce and acknowledge these rights in various countries. In 2010, the World Health Organization (WHO) drafted the Standards for Sexuality Education in Europe, the purpose of which is to help introduce a system of comprehensive sex education from birth. It uses an approach based on an understanding of sexuality as an area of human potential, and helps children and young people develop basic skills that will enable them to decide freely about their sexuality and their relationships in various stages of development. At the same time, it recommends that sexual life should be lived in a fulfilling and responsible way, and supports protection mechanisms against possible risks.

Puberty as an integral part of sex education has been included in school education in the Czech Republic as well as other countries, including strongly religious countries. However, it differs in the overall approach, content, form, but also the age of learners who are educated in this area. In many foreign educational systems, sex education no longer focuses solely on information about unwanted pregnancy and AIDS prevention. It now includes other forms of raising awareness, which requires professional qualification of teachers and other educators. In current European systems, sex education has many common features that can be summarized as follows (Rašková, 2008):

Sex education is usually a mandatory part of education in elementary schools. It is not delivered in the form of a separate subject but is implemented in all subjects (including religion). It is based on coeducation, which requires the teacher to respect the students’ age and individual peculiarities and to use specific methods, forms and means. It is delivered regularly throughout the school year or irregularly in blocks.

It is based on the assumption that the primary role in sex education is taken by the family. The school (or the teacher) can only enrich, complement, develop or support proper education provided by the family and must definitely respect the requirements of the family.

Emphasis is placed on the requirement for professional (particularly methodological) readiness of the sex education teacher.

Sex education is also facilitated by other social entities (various organizations, foundations, special centres, networks of counselling establishments, etc.)

Both Czech and Chinese educational systems have the issue of puberty embedded in their curricula. In the Czech system of primary education, puberty is defined as part of sex education in the national curricular document in the area of Health education. Recently, Chinese education has been subject to a considerable change as a result of the introduction of a new subject – sex education. Sex education, including the issue of puberty, has become a compulsory subject in some Chinese schools, primarily in Beijing and Shanghai; compulsory courses on this topic have even been introduced in some Chinese universities. Sex education in Spain is not included in the national curriculum, but in many schools has become integral part of the school curriculum. The implementation of sex education into the school curriculum is purely within the competence of schools. An important role in the implementation of sex education is played by non-governmental organizations by organizing short interactive thematic seminars. These seminars are usually intended for children up to 12 years of age (Vágnerová, 2000).

The issue presented in this paper is part of a broader educational research study. The empirical research was started in 2015 in the Czech Republic and later included other countries (China, Spain, Sweden). The research focuses on the identification of the cognitive and informative level of knowledge about puberty among primary school pupils, and information about mutual communication about puberty among primary school pupils, their teachers and families. The key concepts of the present research are puberty and knowledge about puberty among primary school pupils.

Pre-puberty and puberty

The issue of pre-puberty and puberty is associated with a period referred to as pubescence and maturing in a broader sense. From a psychological perspective, all of these concepts are defined in different ways. According to professionals, the period of adolescence is a broadly defined stage of life.

Pre-puberty is defined as a transition from childhood to adulthood and precedes puberty. Although a number of professionals have different opinions about the period of pre-puberty and puberty, the age range of pre-puberty is usually eight to eleven years of age, while the age range of puberty is eleven to fifteen years of age. According to professionals, the main features of pre-puberty (also referred to as prepubescence) include the first signs of sexual maturing, occurrence of secondary sex characteristics, and a considerable increase in height. The period of pre-puberty is marked by significant differences in physical and mental development and is considered a period of preparation for puberty. In terms of gender differences, pre-puberty in girls takes place between 11 and 13 years of age, while in boys, physical development is delayed by 1 or 2 years.

Puberty (Vágnerová, 2000) affects a large part of the human life and affects the present and future life. Puberty is a stage in which the reproductive capacity culminates. Puberty can thus be identified as a principal hormonal process of physical changes. In each individual, biological changes are accompanied by mental and social changes. According to professionals, the period of puberty is marked by the age of 13 to 15 years. The reproductive capacity in girls and boys is achieved later. The hormonal processes of physical changes in both genders are associated with changes in the physical structure. During puberty, growth slows down and eventually stops in both genders. During this period, the changes in the physical structure include the development of secondary sex characteristics. Significant psychological changes take place, including becoming aware of one’s personality. In puberty, the way of thinking changes. A new significant aspect is spending leisure time with peers; emotional relationships start to evolve including love and affection.

Knowledge and its cognitive level in the sense of gaining knowledge

Sex education including the issue of puberty has three levels (Rašková, 2008, etc.) The cognitive level represents the tier of gaining knowledge (i.e. the cognitive line in the form of basic information, knowledge, skills and habits). The emotional and relationship level represents model imitation (i.e. the social line in the form of relationships, experiences, models, social learning through imitation). The skills, behaviour and habits level represents relationships (i.e. emotional relationships in the form of high-quality emotional background and interpersonal relationships). These three tiers overlap, cannot exist in isolation and none of them can be omitted. Emotional relationships of a child serve as a basis for behavioural patterns; these models then become a pillar for gaining sexual knowledge. The development of all of these tiers is affected by a number of aspects; the family, school, external environment – world around the child.

Children should be aware of the responsibility for their behaviour, should be able to recognize danger, and should be able to adopt ways of safe behaviour in various situations. In addition to the basic knowledge relating to puberty including for example information about various parts of the human body, reproductive organs, anatomical, physiological and psychosocial aspects of human sexuality, children must develop ethical attitudes to sexuality and be able to avoid risky sexual behaviour. Most information is of a general nature (e.g. puberty, physical appearance, human development, reproductive organs, assertive behaviour, etc.) and is an important part of general knowledge. Children not only have the right to information about puberty, this information also becomes a source of prevention against various risks.

Importance of knowledge about puberty from an educational perspective as a premise of examination

From an educational perspective, the knowledge in the area of puberty facilitates coherent personality development. Knowledge (Janík, 2005) is gained in the process of learning and represents the level of children’s awareness. All children need to be prepared for puberty in time and in an appropriate manner; this should include all associations and contexts related to this stage. Children should learn the required knowledge about puberty before its onset – during pre-puberty when they are in primary school.

In the context of timely preparation for puberty, the present study focuses on younger school-aged children, i.e. primary school pupils. This is the age group of children between 6 and 7 to 11 to 12 years. The focus of the research was on the knowledge about puberty among pupils before its onset. Specifically, focus was on the level of pupils’ knowledge in the area of identification of puberty; puberty age range in both genders; physical and other changes in both genders; its importance for life

Problem Statement

As mentioned in the previous section, children need to learn that they are responsible for their behaviour. They need to be able to alert to and aware of (sexually) inappropriate or dangerous behaviour among those around them, and behave appropriately in various situations. This is crucial knowledge that children should possess as they mature and venture into the world. Children have the right to information about puberty, and furthermore, this information becomes a source of prevention against various risks. Despite this, in many countries around the world, children are denied the right to this crucial knowledge for their sexual and social well-being due to socio-cultural and religious constraints. This research aims to provide much needed information in this area to educational policy makers and educators on the importance of children having this knowledge at their disposal.

Research Questions

The research questions are based on the research problem, which focuses on the investigation of cognitive and informative knowledge about puberty among primary school pupils, and the knowledge about mutual communication about puberty among primary school pupils, their teachers and families. Regarding the fact that the present study includes only a part of a broader research context, the research questions focus on the level of pupils’ knowledge about puberty in the Czech Republic, China and Spain.

The main research question was defined as follows:

What is the level of knowledge about puberty among primary school pupils before its onset?

The main research question was complemented with the following sub-questions:

What is the level of knowledge among primary school pupils that they use to define puberty?

What is the level of knowledge among primary school pupils concerning the age range of puberty in both genders?

What is the level of knowledge among primary school pupils concerning physical and other changes in both genders?

What is the level of knowledge among primary school pupils concerning the significance of puberty for their lives?

Are there any differences in the level of knowledge about puberty between pupils in the Czech Republic, China, and Spain?

Purpose of the Study

As was mentioned above, the present paper describes a part of a research study, which focused on the results of testing of primary school pupils in the context of their cognitive and informative level of knowledge about puberty.

Focus of the study

The cognitive and informative level of learning about puberty represents the tier of gaining knowledge and includes the amount and quality of relevant information (i.e. knowledge) that a child should learn or has learned. The issue of the level of knowledge about puberty among primary school pupils is contextually related to the present educational research. The objective of the comprehensive research was to identify the cognitive and informative level of knowledge about puberty among primary school pupils, and information about mutual communication about puberty among primary school pupils, their teachers and families.

The purpose of the present paper is to publish the results of an analysis of pupils’ knowledge about puberty in the Czech Republic, China, and Spain. This text focuses purely on the selected topic, which is part of a wider research context. The research is carried out as part of Student grant competition at Palacký University in Olomouc (IGA_PdF_2018_011; Comparison of the cognitive and informative level of knowledge about puberty among primary school pupils in selected countries; principal investigator Dr. Miluše Rašková.)

Link to a previous educational research study

The authors of the present study have previously published their results concerning communication about puberty among primary school pupils, their teachers and families (Rašková, Provázková Stolinská, 2015, 2017; Rašková, Provázková Stolinská, & Vavrdová 2015). The results were based on a questionnaire survey and revealed the children’s perspective of communication about puberty with their peers, parents and teachers. In the area of verbal communication, friends and classmates together with the mother and teachers were the sources of information about puberty; if pupils communicated with each other about puberty, such communication took place sometimes or rarely; pupils considered puberty a normal and natural phenomenon; if pupils were able to assess their information about puberty, they considered it sufficient and were interested in learning more.

The survey concerning communication about puberty was performed by means of a non-standardized questionnaire (Hendl, 2006; Chráska 2007). The questionnaire items were classified according to their content into questions about the source of information about puberty (i.e. from whom or from where pupils get information), and its frequency or method of communication (i.e. how often, what intensity, what obstacles etc.) The questionnaire items included scaled, closed and semi-closed questions. The questionnaire items (numbered 10 – 21) followed the test items (numbered 1 – 9) which tested the level of knowledge about puberty.

Research Methods

For the purposes of the present educational research study, relevant methods of data collection, data analysis and statistical inference were used. Statistical data processing was consulted with a professional in statistics.

Methods of data acquisition

The authors of the study tested the cognitive level, which is the pillar of general education of each person. The research method to determine the knowledge about puberty among primary school pupils was an achievement knowledge test (Hendl, 2006; Chráska 2007). The level of knowledge about puberty was tested by means of 9 items with open-ended answers. The content of the test items focused on the definition of puberty (Test item 1); puberty age range in both genders (Test items 2 to 5); knowledge about physical changes in boys and girls (Test items 6 and 7); knowledge about other changes that puberty induces in both genders (Test item 8); significance of puberty in human life (Test item 9). The responses in the test were coded by means of the following numbers: 2 = correct answer, 1= partially correct answer, 0 = incorrect answer. Test items with a missing answer were coded with the number 5.

Data analysis and statistical data processing methods

Methods of descriptive statistics (Hendl, 2006) were used; statistically significant differences in pupils’ responses by countries were identified by means of the non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis test (Hendl, 2006).

Findings

The research was conducted in stages between 2015 and 2018 and is currently being followed up by data collection in other European countries. As was mentioned above, the present study publishes the results of an analysis of pupils’ knowledge about puberty in the Czech Republic, China, and Spain.

Structure of the research sample

The test involved 146 pupils (71 boys and 71 girls; 4 pupils did not specify their gender); the sample was balanced in terms of gender. In China, the test involved 135 pupils (69 boys and 66 girls) of the same age group and gender balance. In Spain, the test involved 26 pupils (12 boys and 14 girls); the sample was balanced in terms of gender. The total of 307 respondents represented the largest age group of 10 to 12 years.

Results

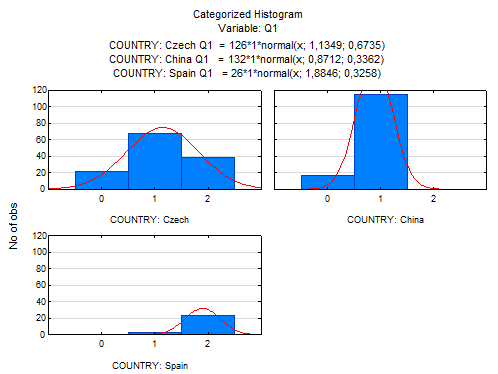

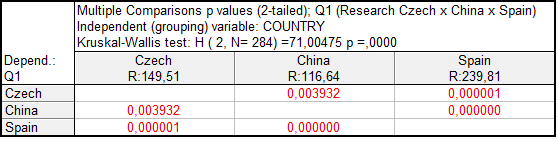

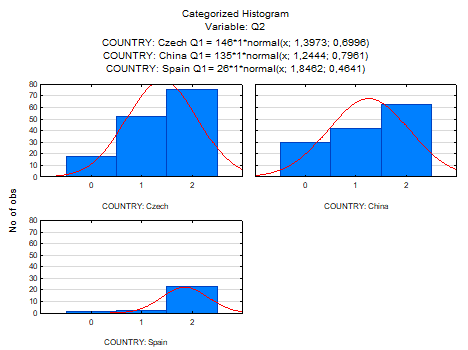

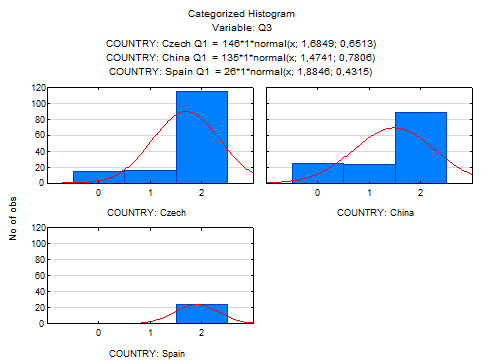

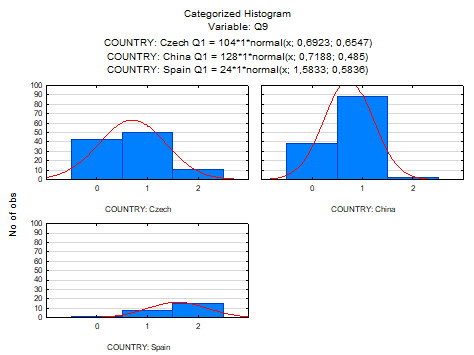

The responses of all participants indicated the level of knowledge about puberty. The following tables and graphs show the results and indicate the level of pupils’ knowledge about puberty (i.e. knowledge required to identify puberty; age range in both genders; physical and other changes in both genders; its significance in life). Correct answers were identified by the number 2, partially correct answers by the number 1, and incorrect answers by the number 0. The responses are summarized in graphs as a comparison of the proportion of numbered responses to individual questions by countries. The tables show a comparison of the achieved point score for individual questions by countries including statistical significance.

Puberty is a stage that follows pre-puberty, in which the reproductive capacity culminates. According to Czech professionals, the period of puberty is marked by the age of 13 to 15 years. Reproduction abilities are achieved later; in girls after the onset of regular ovulation cycle and regular menstruation, in boys after the development of secondary sex characteristics is completed. Puberty can thus be identified as a principal hormonal process of physical changes. A child changes to an adult person who is from a biological perspective ready for reproduction. This process can be identified as maturing. However, the process of maturing should not be assessed only from a biological perspective but also from the perspective of psychological changes that take place along biological changes. Biological and psychological changes are also accompanied by social changes, i.e. gaining a new social status. All changes that take place in the period of maturing are referred to as pubescent changes.

The most frequent answers of the respondents from Spain (correct answer) confirm that they have the knowledge required for the identification of puberty. The answers of the respondents from the Czech Republic suggest partial knowledge, but correct answers prevail. The most frequent answers of the respondents from China confirm that they have partial knowledge. The partial knowledge of the respondents suggest that they do not understand puberty in a comprehensive way. They do not associate the achievement of reproduction ability, full sexual maturity and completion of physical growth with psychological and social changes.

Overall, the difference in the point score of the responses to question Q1 is statistically significant (p<0.01). There is a statistically significant difference in the point score of the responses to question Q1 between all countries (p<0.01).

The issue of puberty is associated with a period referred to as pubescence and maturing in a broader sense. As mentioned above, according to Czech professionals, the period of puberty is marked by the age of 13 to 15 years. This period comes after pre-puberty, which is defined as a transition from childhood to adulthood and precedes puberty. Although a number of professionals have different opinions about the period of pre-puberty and puberty, the age range of pre-puberty is usually eight to eleven years of age, while the age range of puberty is eleven to fifteen years of age. According to professionals, the main features of pre-puberty (also referred to as pre-pubescence) include the first signs of sexual maturing, occurrence of secondary sex characteristics, and a considerable increase in height. The period of pre-puberty, which is a period of preparation for puberty, is marked by vast differences between children in terms of physical and mental development. In terms of gender differences, pre-puberty in girls takes place between 11 and 13 years of age, while in boys, physical development is delayed by 1 or 2 years.

Most of the responses were in the category of correct answer, which suggests that the respondents are knowledgeable about the onset of puberty in boys and girls. The proportion of partially correct answers (or incorrect answers) in the Czech and Chinese respondents suggests that pupils’ knowledge about the onset of puberty in both genders needs to be enhanced.

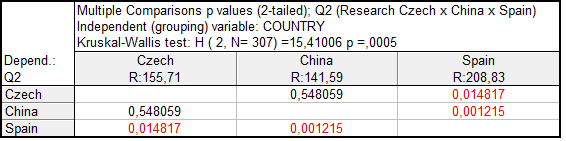

Overall, the difference in the point score of the responses to question Q2 is statistically significant (p<0.01). There is a statistically significant difference in the point score of the responses to question Q2 between the Czech Republic and Spain and between China and Spain.

Overall, the difference in the point score of the responses to question Q3 is statistically significant (p=0.003). There is a statistically insignificant difference in the point score of the responses to question Q3 between the countries.

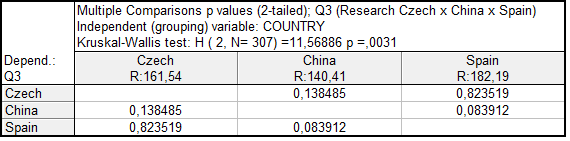

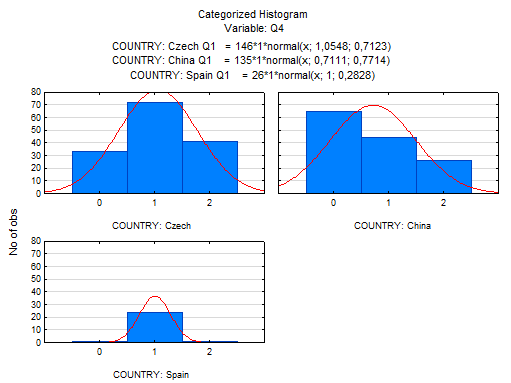

Unlike the area concerning the onset of puberty in both genders, where the responses confirmed pupils’ full or partial knowledge in this area (see text above), their awareness about the end of puberty in both genders is worse. This area is dominated by partially correct or incorrect responses, which confirms insufficient knowledge about the end of puberty in both genders.

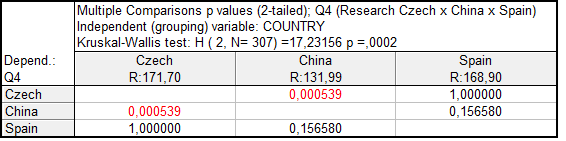

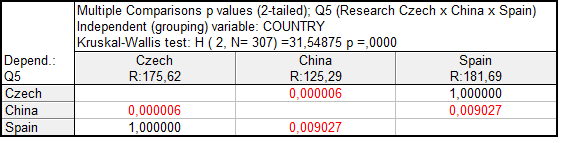

Overall, the difference in the point score of the responses to question Q4 is statistically significant (p<0.01). There is a statistically significant difference in the point score of the responses to question Q4 between the Czech Republic and China.

Overall, the difference in the point score of the responses to question Q5 is statistically significant (p<0.01). There is a statistically significant difference in the point score of the responses to question Q5 between the Czech Republic and China and between China and Spain.

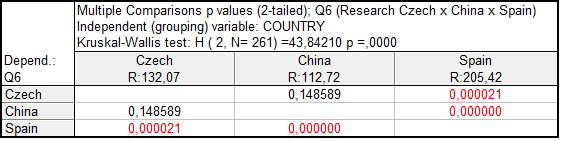

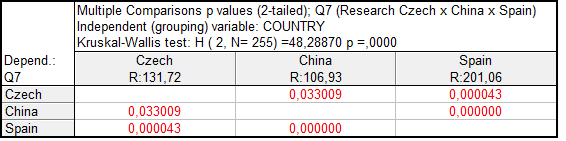

Q6 – Q7

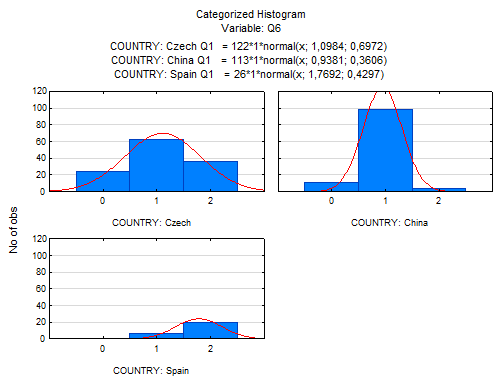

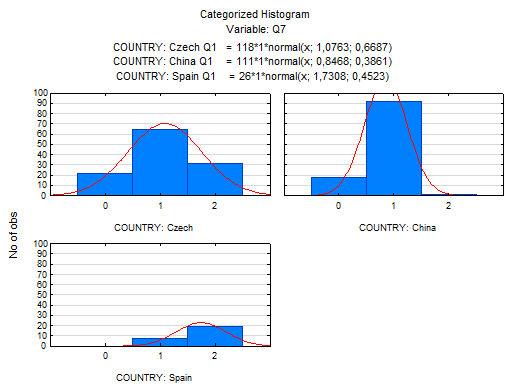

During puberty, the signals concerning the required hormonal changes are sent from the brain to the reproductive organs, which stimulate the growth, development of functions and other changes in the brain and other organs. In line with the hormonal process of physical changes in both genders, during which the reproductive organs mature and start to produce sex hormones (sperms or ova), changes in the physical structure take place. During the period of puberty, growth is decelerated or even stopped in both genders, changes in the physical structure take place, secondary sex characteristics appear including pubic hair in the armpit, skin changes and the development of acne. Changes in boys further include thickening of the body and muscle growth, pubic hair on the scrotum, hair on the face and voice change. Changes in girls include hair in the pubic area, gaining female shape of the body and growth of breasts.

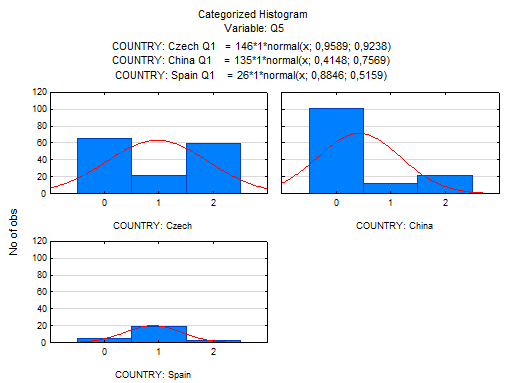

Most of the answers of Czech and Chinese respondents were in the category of partially correct answer, which suggests basic awareness in the area of physical changes during the period of puberty in both genders. These respondents suggested only various incomplete combinations of changes, which means that they do not have appropriate knowledge from a comprehensive perspective. The most frequent answers of the respondents from Spain confirmed their knowledge about the issue.

Overall, the difference in the point score of the responses to question Q6 is statistically significant (p<0.01). There is a statistically significant difference in the point score of the responses to question Q6 between the Czech Republic and Spain and between China and Spain.

Overall, the difference in the point score of the responses to question Q7 is statistically significant (p<0.01). There is a statistically significant difference in the point score of the responses to question Q7 between all countries (p<0.01).

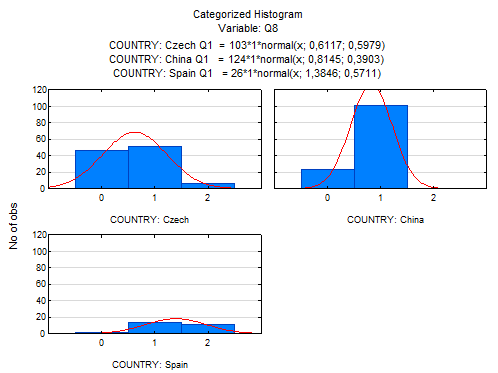

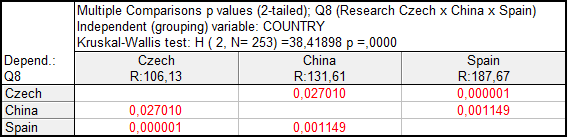

Q8

The period of puberty is marked not only by physical changes but also significant psychological changes including becoming aware of one’s personality. Puberty is a period of searching for and building one’s identity. The manifestations of psychological changes in puberty include refusal of a subordinate role, which changes the social role of an individual and causes attacks against authorities including parents and teachers. The attitude to the school and the teacher changes as well, the teacher is no longer considered a formal authority, only when there is something to be impressed by. Generally, adolescent children want to participate in decision making about matters that relate to them, they start to assess their parents and other adults in a critical way. A significant aspect in the life of an adolescent is spending leisure time. They want to spend time with their peers. Their emotional relationships start to evolve including love and affection. For some individuals puberty may become an impulse for artistic expression, reading complex literary works, doing attractive sports, interest in mysteriousness, romance, nature, and other activities. Pubescents tend to show greater emotional instability. Their self-evaluation changes, they tend to be touchy and vulnerable. According to psychologists, emotional instability is primarily a consequence of hormonal changes. Secondarily, instability may be supported by psychological changes and changes in interpersonal relationships. In puberty, the way of thinking changes. In puberty, individuals start to think hypothetically (at the level of formal logical operations). This change affects their overall attitude to the world but also to themselves.

The answers also suggest the respondents’ awareness of other changes than biological. Most of the responses were in the category of partially correct answer. The respondents indicated only various incomplete combinations of other changes. The most frequent responses included the need to spend leisure time with peers, aspects associated with emotional instability, love and affection, and the need to participate in decision making on matters that relate to them. In this question, the least knowledge was shown by the respondents from the Czech Republic.

Overall, the difference in the point score of the responses to question Q8 is statistically significant (p<0.01). There is a statistically significant difference in the point score of the responses to question Q8 between all countries (p<0.01).

Q9

As was mentioned above, the period of maturing is a broadly defined stage of life. On the one hand, this stage of life is marked by the so-called first signs of sexual maturing including physical growth, on the other hand by achieving the reproduction ability, full sexual maturity and completion of physical growth. However, the process of maturing must not be assessed only from a biological perspective but also from the perspective of psychological changes that take place along biological changes. Biological and psychological changes are also accompanied by social changes, i.e. gaining s new social status.

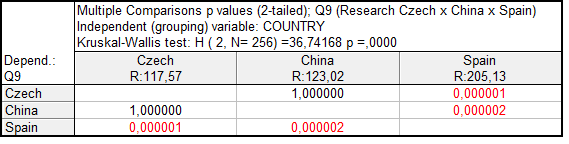

The respondents understand the significance of puberty, which is confirmed by most of the responses in the category of correct answer among the respondents from Spain. The partially correct answers of the Czech and Chinese respondents confirm incomplete or missing knowledge, which contrasted with the answers of the Spanish respondents. The incomplete knowledge suggests that the respondents do not think about the significance of puberty in a comprehensive perspective but rather in various combinations of the biological, psychological and social areas.

Overall, the difference in the point score of the responses to question Q9 is statistically significant (p<0.01). There is a statistically significant difference in the point score of the responses to question Q9 between the Czech Republic and Spain and between China and Spain.

Based on the data obtained from the respondents, it can be concluded that pupils from Spain are informed about puberty before its onset. Their knowledge about puberty is correct except Q4, Q5 and Q8, where they showed partially correct knowledge. Czech and Chinese pupils are informed about puberty before its onset but in comparison with Spanish pupils they showed partial knowledge in questions Q1, Q4, Q6, Q7, Q8 and Q9, and some missing knowledge in all questions Q1 – Q9. Pupils from Spain showed incomplete knowledge only in question Q5.

The incomplete or missing knowledge about puberty suggests that pupils do not consider the issue of puberty and relevant associations and contexts in a comprehensive way. From the perspective of some pupils, the biological aspect and its importance for future reproductive life of each person is not placed in context with other changes. Pupils usually associate puberty only with psychosocial changes. It is desirable to strengthen pupils’ knowledge about puberty in terms of a comprehensive approach to all changes in the biological, psychological and social areas, taking into account the specificity of both genders.

Conclusion

As mentioned in the introduction, sex education in Spain is not included in the national curriculum. The implementation of sex education into the school curriculum is purely within the competence of schools and in many schools has become integral part of the school curriculum. The good knowledge of the Spanish respondents confirm the significance of implementation of sex education in school-based education. The data collection was performed in an elementary school in Madrid, which has the issue of puberty implemented in the system of education.

In Chinese education a new subject of sex education including the issue of puberty has been introduced and is now mandatory in some Chinese elementary schools, primarily in Beijing and Shanghai. In the traditional Chinese society, where sex and sex education is usually a taboo topic, this new school subject has triggered a heated debate. However, the Chinese Ministry of Education argued that sex education was the best way of protecting children. Sex education has become part of teacher training because mandatory sex education courses have been introduced in some Chinese universities.

On a general level, sex education in the Czech Republic is frequently questioned by some parents and the general public as being useless and ineffective in school. Although comprehensive sex education including the issue of puberty should be centred around the family, there is no guarantee that children will receive (provided that sex education does not become taboo) subjectively and socially appropriate information, attitudes and behaviour in the broadest sense of sexual behaviour. Children encounter sexual issues also in other domains of life, for example through the media, especially television, radio, internet, advertisements, books and magazines. These sources of information provide children with a large amount of picture and text information, but also hero imitation motives.

Parents, friends or classmates cannot play the primary role in the formation of knowledge, attitudes and behaviour, because they do not guarantee the relevance of information that they provide. The generation of contemporary parents has usually not undergone any conceptual and systemic sex education in their families or in school, which would lay down the basis of the issue of puberty and communication about puberty. For this reason, the current generation of adults lacks adequate life experience and often lacks the necessary knowledge.

Teachers in schools or other educators focusing on the issue of puberty can significantly contribute to the acquisition of knowledge about puberty. Curricular or extracurricular education of this issue must be delivered in schools in a qualified way, taking into account various educational and psychological particularities of pupils and respecting humane approaches and ethical principles. Teachers and other educators should be professionally and didactically prepared for education about puberty. Communication about puberty in a school environment is the professional responsibility of the teacher (Štěrbová, Rašková, 2014). The role of the school is, through the teacher, to provide the knowledge about puberty, but also to lay the foundations of attitudes and guidelines for decision making.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank their Chinese colleague Wan Zhang Wei for excellent cooperation in the implementation of the research in China. We would also like to thank our colleague Alena Vavrdová who cooperated with our Spanish partners. Last but not least, we would like to thank Miroslav Chráska Jr. for statistical processing of the results. Our thanks also go to all students who participated in the research.

References

- Hendl, J. (2006). Přehled statistických metod zpracování dat. Analýza a metaanalýza dat. Praha: Portál.

- Chráska M. (2007). Metody pedagogického výzkumu. Základy kvantitativního výzkumu. Praha: Grada Publishing,

- International Planned Parenthood Federation. b. (n.d.) Comprehensive sexuality education. Retrieved from: http://www.ippf.org/our-work/what-we-do/adolescents/education

- Janík, T. (2005). Znalost jako klíčová kategorie učitelského vzdělávání. Brno: Paido.

- Rašková M. (2008). Připravenost učitele k sexuální výchově v kontextu pedagogické teorie a praxe v české primární škole. Olomouc: VUP.

- Rašková M. & Provázková Stolinská D. (2015). Cognitive and informative level of knowledge about puberty of Czech elementary school students. Bulgaria: SGEM.

- Rašková M. & Provázková Stolinská D. (2017). Communication about puberty between children of middle school age and parents. 8th World Conference on Learning, Teaching and Educational Leadership.). Portugal: WCLTA.

- Rašková M. & Provázková Stolinská D. (2015). Puberty as the concept of pedagogical theory and practice. Vienna: IAC-TLEI.

- Rašková M. & Provázková Stolinská D. (2017). Teacher-Student Communication about Puberty in Elementary School. Ireland International Conference on Education. Dublin: IICE.

- Rašková M. & Provázková Stolinská D. & Vavrdová A. (2015). Educational premises of puberty at primary school. Olomouc: ICLEL.

- Rámcový vzdělávací program pro základní vzdělávání. [on-line] Retrieved from: http://www.msmt.cz/vzdelavani/zakladni-vzdelavani/upraveny-ramcovy-vzdelavaci-program-pro-zakladni-vzdelavani

- Štěrbová D. & Rašková M. (2014). The Specifics of Communication in Relation to Sexuality I: Helping Professions in Relation to Sexuality, Including Persons with Intellectual Disabilities. Olomouc: Palacký University.

- Vágnerová M. (2000). Vývojová psychologie. Dětství, dospělost, stáří. Praha: Portál.

- WHO Regional Office for Europe and BZgA. (2010). Standards for Sexuality Education in Europe. Retrieved from: http://www.bzga-whocc.de/?uid=20c71afcb419f260c6afd10b684768f5&id=home

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

14 January 2019

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-052-5

Publisher

Future Academy

Volume

53

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-812

Subjects

Education, educational psychology, counselling psychology

Cite this article as:

Rašková, M., & Stolinská, D. P. (2019). Description Of Knowledge About Puberty Among Primary School Pupils In Selected Countries. In Z. Bekirogullari, M. Y. Minas, & R. X. Thambusamy (Eds.), ICEEPSY 2018: Education and Educational Psychology, vol 53. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 457-475). Future Academy. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2019.01.44