Abstract

This study compares the views of preschool teachers against those of preschoolers’ mothers’ towards the peer relations of preschoolers to determine the similarities and differences. The early childhood years are vital for the establishment of peer groups; thus, both preschool teachers and families are hold responsible for supporting social interactions among peers. Perspectives about peer relations of preschoolers may be detrimental on teachers' and parents' acts concerning the current phenomenon. Therefore, understanding the perspectives of those agents is important in providing appropriate education. The research employed a basic qualitative research design in order to understand the particular viewpoint. Interviews were used to learn about participants’ viewpoints, experiences and meaning making about the current phenomenon. While mothers view teachers as the first responsible agent for supporting peer relations, teachers also considered families as the most responsible agent. Teachers mostly mentioned about family and child oriented factors related with peer relations while mothers reflected teacher, child and peer oriented factors. Lastly, teachers and mothers reflected their views on challenges/concerns related with peer relations. Teachers need to use family as a source of knowledge about children and study with them collaboratively and consistently to create mutual ways of supporting children’s peer relations, which will contribute to children’s long-term development and learning. Furthermore, teachers need to be in consistent contact with the parents of children to support preschoolers' peer relations.

Keywords: Peer relationsearly childhoodteachermother

Introduction

Socialization and learning in early childhood mainly occur through interactions children engage in with their peers and their teachers in social contexts (Ladd, 2005; Pianta, 1999). These interactions in early childhood include social interaction with various agencies like peers, siblings, parents and teachers (Henderson & Atencio, 2007) and those agencies have a kind of responsibility in supporting the children’s well-being in various developmental areas (Semrud-Clikeman, 2007). Teachers can guide the classroom’s social dynamics and support children’s peer interactions in the classroom environment (Farmer, McAuliffe, Lines, & Hamm, 2011) while parents may be influential on the socialization process of their children (Ladd, 2005). Beside socialization, parent-child interaction affects children’s behavior (Lindsey, Cremeeens, & Caldera, 2010; Michiels Grietens, Onghena, & Kuppens, 2008). Families can engage in some roles like organization of play time, being a role model for peer relations to encourage their children to be involved in social interactions that contribute to their peer relations (Niffenegger & Willer, 1998). Therefore, the parent-child relationship is crucial in understanding children’s peer relations.

This study aimed to compare the views of preschool teachers against those of mothers’ towards the peer relations of preschoolers to determine the similarities and differences. It is hoped that the information gathered by this study will be used by early childhood professionals and parents to encourage them in becoming aware of their own role in promoting social interactions both inside and outside school contexts.

Peer Relations in Early Childhood

When we look at the development of peer relation through the years, we see that, in the first two years of life, children tend to form groups of two at most while when they became three-year-old, they start to enlarge their play groups. In these three years of life, children may experience a kind of disagreement especially on the issue of sharing and even they may tend to use physical aggression toward their peers due to their language inadequacies (Hay, 2006). It was observed that, children at the age of five have a tendency and willingness to have a contact with peers and also they develop a tendency to engage in group play (Erwin, 1993). Signs of sympathy, sharing, companionship were displayed mostly when children become six year old as well as fight, competition and conflict (Hay, 2006). Children’s peer preferences started to be shaped in the ages of four to five (Gülay, 2010). Through engaging in play activity, children’s peer interactions established and later on enhanced by adults through facilitating and guiding (Kemple & Hartle, 1997).

Role of Various Agents in Pre-schoolers’ Peer Relations

On one hand, children hold an active role in playgrounds in means of selecting the activity and the role engaged in, deciding on a place or an interest corner, and determining partners to play with (Berk & Winsler, 1995; Yang, 2000). On the other hand, teacher can facilitate for the formations of playgroups, can encourage passive children to join and create a spontaneous play environment (Gmitrova & Gmitrov, 2003). Observation of children’s activities, play and facilitation of it when necessary by teachers is crucial in the formation and maintenance of peer relations (Bennett, Wood & Rogers, 1997). Involvement of an adult may be required for peer relations through supporting, facilitating and intervening children’s interactions (Kemple & Hartle, 1997) as well as children’s active role in their peer relations. Therefore, teacher-child relationships have an important role in the peer relationships of children (Hamre & Pianta, 2007; Shin & Kim, 2008). Similarly, as Howe (2010) stressed, depending on teacher’s organization of the classroom activity, children can form some peer groups, can make some social inferences about their peers and can develop some kind of attitudes in the degree of liking or disliking. The role of teacher- child relationship is more effective when children are in their preschool years (Howes, Hamilton & Matheson, 1994). Children spend most of their times in preschools and involve in social interactions and peer relationships which enable them to be participate in socialization process and even enable most of children to get the first chances for learning to engage in social interactions and form peer groups (Spivak & Howes, 2011). It was stressed that, children have an inclination for relying on teacher’s opinions about peers and also structure their peer relationships accordingly in the direction of teacher’s approval or disapproval (Costanzo & Dix, 1983; Hughes & Chen, 2011; Shin & Kim, 2008, McAuliffe, Hubbard, & Romano 2009). Teacher feedbacks have an effect on the children’s peer preferences, perceptions and attitudes towards peers (White & Kistner, 1992). In other words, the nature of the relationship formed with teachers form the bases of the peer relationships of children since children tend to make use of the teacher’s presence as a support or source for engaging in peer relationships (Howes, Matheson, & Hamilton, 1994). As Stanton- Chapman (2015) stressed, teacher involvement is crucial in guiding and scaffolding the interactions of children inside the classroom for achieving appropriate ways of playing with peers.

Other than teachers’ role, parents’ approaches may indirectly affect the interactions children establish with their social world (Paterson & Sanson, 1999). As Acar, González, Kutaka, and Yıldız (2018) stressed, parent-child relationship can make a contribution to children’s peer relations. Parents can constitute a relationship model for their children which enable children imitate and observe for their following learning (Simpkins & Parke, 2001). Moreover, quality of the parent-child relationship is a key for children’s social interaction patterns in that, children deprived of responsive, sensitive, and consistent parenting are more likely to experience peer problems in their following periods (Fagot 1997).

Problem Statement

There is a lack of empirical studies particularly in the Turkish context that address the concerns of scholars in the area. Causal factors involved in preschool children’s development specifically on the role played by teachers and parents are the main focus of the study. Correspondingly, in its emphasis on perspectives of teachers and mothers, the present study is critical for providing diverse viewpoints regarding peer relationships among young children in and out of the classroom, which may suggest important role of the teacher’s and mothers on the peer relations of children.

Purpose of the Study

This study aimed to compare the views of preschool teachers against those of mothers’ towards the peer relations of preschoolers to determine the similarities and differences. Given the important role of teachers and parents in social interactions and peer relations of preschoolers, some strategies may be inferred from this study to arrange social interaction opportunities of children that they engage inside and outside the classroom.

Research Questions

-

What are the views of parents and mothers on the responsible agents for the peer relations of preschoolers?

-

What are the parents and mothers perceived factors related with peer relations of pre-schoolers?

-

What are the parents and teachers experienced challenges / perceived concerns related with peer relations of preschoolers?

Research Methods

Design

The research employed a design of basic qualitative research in order to understand the particular viewpoint. Through basic qualitative research design, researchers can understand the interpretations of experiences of people, their construction of the world around them and meaning making processes (Merriam, 2009). “The overall purpose is to understand how people make sense of their lives and their experiences" (p. 23). Interviews were determined to be used to learn about participants’ viewpoints, experiences and meaning making about the current phenomenon.

Participants

10 teachers and 51 mothers were participated in the study. Purposeful sampling was used to reach participants. 10 teachers were selected among the three private early childhood institutions in Turkey. The distribution of teachers and mothers were given under the Table

Data collection tool

Data were collected through semi-structured interview teacher-mother versions, which include 13 questions in each. There are also some demographic questions covering the participants’ ages, genders, graduation degree, required courses they had completed (teacher version). An expert opinion was gathered from four academicians from the field of early childhood education. Two of the experts also have the doctorate degree in early childhood education. After gathering expert opinion on the interview questions, the number of interview questions was reduced to 11. The revised protocol was piloted with one preschool teacher and three parents.

Data collection procedure

Firstly 10 teachers studying at three different early childhood center were reached and became volunteered to participate and signed consent forms. Appropriate times of volunteer teachers were arranged and they were then interviewed one by one in appropriate rooms provided by the schools. All participant teachers consented to audio-recording. The duration of teacher interviews lasted between 20 and 30 minutes. For the mother interviews, teachers were requested to announce the study for the parents inside their classrooms and ask for volunteer parents to be included in the interview process. Out of parents of children 138 only 56 of them sent an acceptance letter for the participating in the study and all of them were the mothers of their children. Appropriate time for interviewing was tried to be arranged with the mothers either conducting the interview in school, in their home or any other place by considering their convenience. While arranging an appropriate time, 5 of the mothers could not spend required time for the interview. Therefore, in total 51 mothers were interviewed at the end. The duration of mother interviews lasted between 15 and 25 minutes.

Data analysis

Recorded interviews were transcribed by the researcher and then both the researcher and a second coder read the transcripts separately several times and coded the data. The second coder has experience in qualitative data analysis, qualitative research and had a doctorate degree in early childhood education area. Analysis of the data was started with the coding of the transcripts. As Merriam (2009) stated, coding means, taking notes near the data for facilitation of finding answers to the research questions. In a similar way, Rubin and Rubin (1995) defined the coding as the process of organizing data into categories that are sound to refer similar thoughts and concepts. After coding the data, all codes were listed and similar topics were clustered together. Afterwards, most descriptive wording has been found for forming the categories. In order to emphasize the importance of participants’ ideas, besides reporting the themes and codes, in the study, clarifying quotes were directly taken and incorporated into the results in order to enrich the description of the themes (Creswell, 2007).

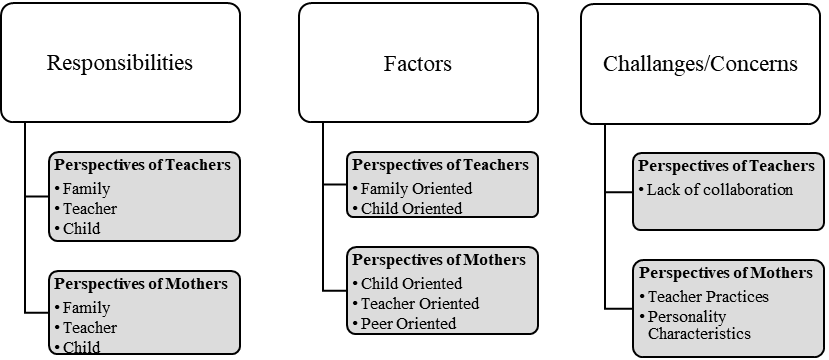

Data was analyzed inductively and process of open coding was conducted. A computer software program namely “ATLAS.ti 7” was used for assisting the analysis of the study. Coding was listed under some categories representing perspectives on peer relations of teachers and mothers. Through carefully reading coding and quotations, some were merged together and some were discarded with the agreement of the second coder. Data analysis yielded three main themes namely; (1) Responsibilities, (2) Factors, and 3) Challenges. Figure

Trustworthiness

Non-directional questions were directed toward participants by avoiding socially desirable questions (Creswell, 2008). Direct quotations were given place for presenting accuracy of data. By using rich and thick description (Patton, 2002) in means of quotations, setting, etc., the reader can easily understand what the researcher wants to say and be knowledgeable about shared experiences and the setting. Through this means, low inference descriptors were used. Moreover, through getting consultation from experienced qualitative researcher investigator bias can be minimized. This act can be classified as a peer examination and thought to be a kind of strategy to provide validity in the study (Creswell, 2007). In the direction of this validity consideration, approximately 20% of the interview transcripts were conducted with the presence of the second coder who holds similar academic background with the researcher. Recruiting the second coder can help for ensuring the reliability and the validity of the results (Merriam, 2009). Codes, about which the researcher and the second coder could not reach an agreement on, representing 4% of the total codes, were omitted from the analysis.

Findings

Responsibilities

When participant teachers asked about their views on the responsibilities and role of various agents on the peer relations of children; while mothers view teachers as the first responsible agent for supporting peer relations of their children, teachers also considered families as the most responsible agent. Both teachers and mothers viewed children as least responsible source as it can be seen in the Table

Most of the participant teachers (n=7) considered peer relationship formation as the fact that occurred inside the family. They stressed that, they believe most of the peer relationship problems based on the wrongly formed behavioral patterns that children established in their home environment. In that sense, they see family as a source of responsibility. As one of the teacher puts it;

Children are like video recorder, they record their surrounding world, like family and neighbors. Those environment functions as a role model for children. Through time, children start to believe that those behaviors are the realities and start to model them. Therefore, I believe that the behaviors and attitudes of family members, children of neighbors have a crucial effect on children’s attitudes and behaviors. So the behaviors that we are exposed to inside the classroom toward their peers unfortunately are the products of their surroundings. (T4)

Besides mentioning about families’ great responsibilities on peer relations, teachers also reported some responsibilities which are suited for them. All of them stressed that, teachers hold great responsibility in the formation of peer relations and in helping children in dealing with peer relations. In addition to the report of being a role model for children, teachers also reported that, they can take role in scaffolding children’s peer relations in the classroom environment. While some of them stressed that teacher can hold an intervention role in peer relation (n=6), some of them expressed that they should facilitate positive relationship among children (n=4) without intervention. One of the teachers who disagree with the intervention role noted that;

Forcing children to form groups with some others, physically replacing children’s places…I see those attempts as teacher oriented and do not make children happy. Think about yourself, could you imagine spending the whole day with a friend that your energy did not fit? It is impossible. Forcing children to play with specific peers means intervention to children’s rights. (T1)

Contrary to the teachers’ views on responsibilities of their own and parents’ on the peer relations, only one of the teachers considered children as the most important agent responsible on their own peer relationship. She stressed that, beside the teacher and parents’ role on the peer relations children need to learn how to manage their own relationship with their peers. One of the teachers puts it as;

We as teachers are here to teach children the world around them. We as parents and teachers act as a defender of their own lives. We determine whom they need to work with or play with. Even sometimes I found myself in the position of determining their learning centers they play in. But there is one thing that we miss; they need to survive on their own. If we do all the things for children now, we just only create prisoners who are dependent on our presence. Children independently have the power for creating their own cliques. (T8)

In a similar way, mothers also reported some responsibilities related with peer relations of children. 41 of the mothers stated that, teachers hold the primary responsibility for the peer relations of their children. Only 6 of them view parents as the primary responsible agent for the peer relations of children. Only four of them view children themselves holding crucial role in the peer relations but added that children alone could not manage this process. They need more knowledgeable agents who are parents and teachers. Some of the mothers reflected their responses related with the teachers’ being the primary agent as;

My child spends most of his time inside the school with his friends and the teacher. Sometimes I feel like I could not give appropriate attention to my child since we saw each other for a limited time. For some days even I could not see my child’s face. That’s why teacher is really important in giving appropriate education. Sometimes teacher of my child recognize interest and needs of my child better than me. (M22)

As it can be seen, mothers view themselves very detached from their children while perceiving teachers’ presence as core in their children’s life.

Factors

When teachers were asked about factors affecting peer relations of children, they mostly mentioned about family oriented ones like;

Majority of teachers (n=7) reported their perspectives on the familial attitudes and practices that they believe have an effect on the peer relations of children. Most of the participant teachers reported their perspectives on the parents’ practices in setting limits for their children. Teachers stated that, most of the families reared their children as unique and when they meet inside the classroom problems arise. One of the teachers expressed it as;

Families raise their children as spoiled and selfish. They saw their child as prince. Make their children believe in their uniqueness. This may support children self-confidence but when this child comes to class, the problem arises. Think the situation in which there are lots of prince and princess. They start to insist on their own wants and do not understand that his/her peer also have right to have the same desire… So parents are really important in that sense. (T6)

Other than child-rearing practices, some of the teachers specifically mentioned about out of school practices that prevents children to appropriately function inside the classroom. For example, one of them (T5) stressed that, due to the parents’ imposing ideas about some specific children, children may miss chance of benefiting from other peer groups. She thinks that, this kind of familial impositions make children cling on one specific peer and play with that peer all the time which reinforce the polarization between peers. Another teacher added that,

There are some children who know each other from their old school or due to their familial relationship. They also meet with each other in weekends or in some other places and times. For example, I’m witnessing that, in the morning, when mother left her daughter to school, telling that ‘play with x, sit near x and don’t leave her’. Those children function as if twins inside the class and exclude other children. I don’t consider it appropriate. (T10)

Participant teachers also brought up another factor which was grandparents and they expressed it as out of school practices. They think that due to some families’ work conditions, grandparents take care of their children which they believe affect children in negative ways. They perceive grandparents’ position as doing all the desires of children which cause children to understand setting limits or delaying their gratifications. These kinds of behavioral patterns learnt from grandparents are believed to make child expect peers to behave as the same toward them.

Other than familial factors, teachers also mentioned about child related ones which are related with the personality characteristics of children. They reported their views on the some of the temperamental chacteristics of children like being introverted, extraverted and agreeableness are effective on the peer relations of children. Half of the teachers (n=5) stressed that, temperament of children may determine what kind of practices the child will engage in the classroom. One of the teachers expressed it as;

Whatever strategy you implement for the shy child, it doesn’t differ. You can’t make it popular inside the group of peers. Despite of all of my attempts and her parents’, I couldn’t make such an admiring member of peer groups. She needs assistance for involving in groups still...I guess genes are important in that sense. (T3)

Other than teachers, when mothers are asked about factors affecting peer relations of children, they mostly mentioned about child oriented factors like personality characteristics similar with teachers’ views, teacher oriented factors like classroom practices and peer oriented factors. Majority of the mothers (n=42) expressed their views about the factors related with temperamental characteristics of children affecting their child’s peer relations. Beside child oriented factors, as a teacher oriented factors, classroom practices and peer oriented factors were mentioned by mothers (n=12). They expressed their views on the perceived factors of in-class activities and practices conducted by teachers. For example, they stressed that, due to some practices reinforced by teachers (rules, seating plans, etc.) their children’s peer relations are affected. Similarly, peers also mentioned by the mothers (n=13) as a determinant factor on their children’s peer relations. They stressed that, most of the behavioral patterns are believed to be learnt from the peers of their children. It is mentioned by some of the mothers in this way;

One day my child started to slang word and was using it in every sentence he talked. I really disturbed because we don’t use it ever. When I searched for its origin, I realized that his friend is using it inside the class. Sometimes I couldn’t recognize my child’s behaviors even if he is 5 years old. Peers are such influencer. (M35)

Challenges/Concerns

When participant teachers asked about their views on the perceived challenges of peer relations / concerns related with peer relations, they stressed lack of collaborations between parents. They mostly stressed inability to communicate with some of the parents due to their intensive work conditions (n=7) or unwillingness to establish communication (n=5). In addition, they stressed that, since most of the parents are unwilling to engage in family involvement practices, they could not visualize what is going inside the classroom. Moreover, due to their inability to involve, their child may feel anger which in turn affects peer and family relations negatively. One of the teachers mentioned about it by saying;

Most of my parents are working that’s why I couldn’t force them to involve in family practices but due to their inability to involve in those, their children feel lonely. Because they see that their friend’s parents can come. They compare their situations necessarily. So the child may feel anger towards both his friends (whose family involved in class) and also his/her parents. We experienced lots of cases like this. (T9)

Other than busy parents, teachers also mentioned about some parents who are not open to communication. They stressed that working together with the family, exchanging the information, giving them the feedback about their children’s relationships with peers are really beneficial. Teachers mentioned about those as constituting a serious concern since they does not help teachers in dealing with some peer relationship problems. They mentioned about those levels of involvement by either physical absence or physically present but do not take feedback.

On the contrary to parents who are not open to communication, teachers also expressed their views on the parent intervention related with peer relations (n=6). Those teachers who mentioned about intervention of parents families reflected their views on it as parents should not interfere the ongoing interactions of their children with their peers and also should not intervene the interactions inside the classroom. They exemplified those as, verbalizing some peer selection requests or preferences for play partners. One of the teachers stressed it by saying;

Some of the parents want us to behave in the direction of their wishes in means of their children’s peer relations. They even put their nose into our job by requesting to make specific child not to sit with their children or not make a play partner of their child. They should not feel that courage for such intervention. (T8)

Besides teachers concerns, mothers also hold some concerns related with peer relations of their children. Some of them collected under the subtheme of teacher practices while some of them related with personality characteristics. Although some of the mothers did not mention about any concern related with their child’s peer relations (n=21), some of them mentioned about some such as being not sure about the relationship inside the classroom both between teacher and their children (n=15) and also between other peer and their children (n=17). Mothers who have concern related with teacher practices and teacher-child relationship listed their anxieties on fairness and expression of love of teachers’ toward their children. They stressed that, they have witnessed some inequalities expressed by teacher towards specific children in means of not giving equal attention, love and tolerance. They expressed their view that this may create other peers behave in the way teacher behaves. Some of the mothers put it as;

I realized that my child started to keen on a specific peer and put forward some praises to her as well as some intrinsic jealousy…through time when I talk with some other parents I learnt that the teacher were so keen on that child and verbalize her compliments towards the girl in front of the class. Teachers should stand in equal distance to all… Sometimes I feel as if my child’s behaviors are not tolerated by the teacher that much when compared to other children (M46)

Beside those concerns of mothers, some of the mothers reported some concerns related with the weakness of the teacher’s reporting on the peer relations of their children. They stressed that, throughout the semester they only contacted for materials that should be brought into classroom or some serious behavioral problems. They stressed their belief that, there should be sometimes that teachers should contact with them about the positive behaviors or their child’s peer relations either by written notes or with meetings. One of the mothers noted it as;

When teacher calls me to school I feel very nervous, anxious… I immediately think that my child did something wrong. Mostly, she calls me rarely, only in situations of some concerns or problems. Why don’t they call us for positive things? I always think of. (M31)

Conclusion

The current study explored the views of preschool teachers against those of mothers’ towards the peer relations of preschoolers. Some main findings are noteworthy to discuss. First, while mothers view teachers as the first responsible agent for supporting peer relations of their children, teachers also considered families as the most responsible agent. Second, while teachers attributed peer relations to family and child oriented factors, mothers mentioned about child, teacher and peer oriented ones. Lastly, while teachers perceived lack of collaboration and parents’ interventions as challenge to peer relations, mothers perceived teacher practices and personality characteristics as challenges.

In the light of the findings of the study, teachers need to use family as a source of knowledge about children and study them collaboratively and consistently to create mutual ways of supporting children’s peer relations, which contribute to children’s long-term development. As Ladd (2005) stressed, the peer relationship quality is effective on the long-term adjustments of children. Child rearing and parent-child interaction styles can determine the peer relations of children (Ladd, & Pettit, 2002). Therefore, being in consistent contact with the parents would be beneficial in the long run for children’s social competence and peer relations. Parents should also be asked to provide their ideas about their children’s peer relations outside of school. Perceptions about their children, needs and questions can be learnt and an appropriate intervention can be designed accordingly.

As Gülay (2010) suggested, families who have some concerns related with peer relations of their children can meet with each other for facilitating an exchange of views. In addition, developmental reports can also be used for giving information about children’s peer relationships in the classroom context. Moreover, although mothers and teachers considered themselves as the responsible agents for their children’s peer relations, they rarely considered children as the responsible agent for their own peer relations. These attributions deserve attention to study in further research.

In addition, there is a need for teachers to become educated in applying formal assessment tools for identifying and addressing children’s peer relations. As the current study indicated, mothers reported some concerns related with lack of teachers’ reporting on peer relations. Through using developmental reports in a meaningful way, some of the concerns of mothers can be lessened through informing them in details and some of the communication deficits between teachers and parents can be dealt with. Furthermore, by making emphasis on the important role of the teachers’ in the process of affecting thoughts and values of children towards their peers, teachers should be encouraged to consider their attributions for children’s behaviors by considering their potential to form a role model (McAuliffe et al., 2009). Children can be affected by teachers’ behaviors, and they can use those behaviors as a guide while behaving towards their peers (Mikami, Griggs, Reuland, & Gregory, 2012).

As both teachers and mothers reported, peer relations were attributed to the child related factors like personality characteristics. It was supported in the literature that, peer interactions between children are affected from the temperamental characteristics of children in preschool (Acar, Rudasill, Molfese, Torquati, & Prokasky, 2015). Therefore, temperamental characteristics of children should be assessed and considered inside the classroom through implementing different strategies suitable for different temperaments for supporting peer interactions. Parallel with awareness in temperamental chacteristics, teachers can implement some strategies to promote peer interactions inside the classroom (Audley-Piotrowski, Singer, & Patterson, 2015).

Teachers and parents may benefit from the current study by discovering new practices to promote children’s peer relations. Teachers can focus more on the positive social interactions among children and can identify the children who need help with their social interactions and intervene when needed. In its emphasis on subjective experience, the present study is critical for providing teachers’ and mothers’ diverse viewpoints regarding relationships among young children in and out of the classroom, which may generate various responsibilities and consistencies between their practices.

References

- Acar, I. H., González, S. P., Kutaka, T. S., & Yıldız, S. (2018). Difficult temperament and children’s peer relations: the moderating role of quality of parent–child relationships, Early Child Development and Care, Advance Online Publication, 1-15. Retrieved from DOI: 10.1080/03004430.2018.1439941.

- Acar, I. H., Rudasill, K. M., Molfese, V., Torquati, J., & Prokasky, A. (2015). Temperament and Preschool Children’s Peer Interactions, Early Education and Development, 26(4), 479- 495.

- Audley-Piotrowski, S., Singer, A., & Patterson, M. (2015). The role of the teacher in children’s peer relations: Making the invisible hand intentional. Translational Issues in Psychological Science, 1(2), 192- 200.

- Bennett, N., Wood, L., & Rogers, S. (1997). Teaching through play: Teachers’ thinking and classroom practice. Open University Press: Buckingham, Philadelphia.

- Berk, L. E., & Winsler, A. (1995). Scaffolding children’s learning: Vygotsky and early childhood education. Washington, DC: NAEYC.

- Costanzo, P. R., & Dix, T. H. (1983). Beyond the information processed: Socialization in the development of attributional processes. In Higgins, E. T., Ruble, D. N., & Hartup, W. W. (Eds.), Social Cognition and Social Development: A Sociocultural Perspective (pp. 63- 81). Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

- Creswell, J. W. (2007). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches.Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

- Creswell, J. W. (2008). Educational Research. Planning, Conducting, and Evaluating Quantitative and Qualitative Research (3rd Ed.). Pearson Education: New Jersey.

- Erwin, P. (1993). Friendship and peer relations in children. Chichester, England: Wiley.

- Fagot, B. I. (1997). Attachment, Parenting, and Peer Interactions of Toddler Children. Developmental Psychology 33, 489–499.

- Farmer, T. W., McAuliffe Lines, M., & Hamm, J. V. (2011). Revealing the invisible hand: The role of teachers in children’s peer experiences. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 32, 247-256.

- Gmitrova, V., & Gmitrov, J. (2003). The impact of teacher- directed and child directed pretend play on cognitive competence in kindergarten children. Early Childhood Education Journal, 30 (4), 241- 246.

- Gülay, H. (2010). Okul Öncesi Dönemde Akran İlişkileri [Peer Relations in Early Childhood]. Pegem Akademi: Ankara.

- Hamre, B. K., & Pianta, R. C. (2007). Learning opportunities in preschool and early elementary classrooms. In R. C. Pianta, M. J. Cox, & K. Snow (Eds.). School readiness and the transition to kindergarten in the era of accountability (pp. 49-83). Baltimore, MD: Paul H. Brookes.

- Hay, D. F. (2006). Yours and mine: Toddlers’ talk about possessions with familiar peers. British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 24, 39-52.

- Henderson, T. Z., & Atencio, D. J. (2007). Integration of play, learning, and experience: What museums afford young visitors. Early Childhood Education Journal, 35, 245- 251.

- Howe, C. (2010). Peer groups and children’s development. Wiley-Blackwell Publication: United Kingdom.

- Howes, C., Hamilton, C. E., & Matheson, C. C. (1994). Children’s relationships with peers: Differential associations with aspects of the teacher- child relationship. Child Development, 65, 253- 263.

- Howes, C., Matheson, C. C., & Hamilton, C. E. (1994). Maternal, teacher, and child care history correlates of children’s relationships with peers. Child Development, 65, 264- 273.

- Hughes, J. N., & Chen, Q. (2011). Reciprocal effects of student-teacher and student-peer relatedness: Effects on academic self-efficacy. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 32, 278-287.

- Kemple, K. M., & Hartle, L. (1997). Getting along: How teachers can support children’s peer relationships. Early Childhood Education Journal, 24(3), 139- 146.

- Ladd, G. W. (2005). Children’s peer relations and social competence: A century of progress. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

- Ladd, G. W., & Pettit, G. S. (2002). Parenting and the development of children’s peer relationships. In M. Bornstein (Ed.), Handbook of parenting (2nd ed., pp. 269–310). Mahwah, NJ:Erlbaum.

- Lindsey, E. W., Cremeeens, P. R., & Caldera, Y. M. (2010). Mother–child and father–child mutuality in two contexts: Consequences for young children’s peer relationships. Infant and Child Development, 19, 142–160.

- McAuliffe, M. D, Hubbard, J. A., & Romano, L. J. (2009). The role of teacher cognition and behavior in children’s peer relations. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 35, 665-677.

- Merriam, S. B. (2009). Qualitative research: A guide to design and implementation. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- Michiels, D., Grietens, H., Onghena, P., & Kuppens, S. (2008). Parent-child interactions and relational aggression in peer relationships. Developmental Review, 28, 522- 540.

- Mikami, A. Y., Griggs, M. S., Reuland, M. M., & Gregory, A. (2012). Teacher practices as predictors of children’s classroom social preference. Journal of School Psychology, 50, 95- 111.

- Niffenegger, J. P., & Willer, L. R. (1998). Friendship behaviors during early childhood and beyond. Early Childhood Education Journal, 26(2), 95- 99.

- Paterson, G., & Sanson, A. (1999). The Association of Behavioural Adjustment to Temperament, Parenting and Family Characteristics among 5‐Year‐Old Child. Social Development, 8(3), 293-309.

- Patton, M. Q. (2002). Two decades of developments in qualitative inquiry: A personal, experiential perspective. Qualitative social work, 1(3), 261-283.

- Rubin, H. J., & Rubin, I. S. (1995). Qualitative Interviewing. The Art of Hearing Data. Sage Publication: Thousand Oaks, California.

- Semrud-Clikeman, M. (2007). Social competence in children. USA: Springer.

- Shin, Y., & Kim, H. Y. (2008). Peer victimization in Korean preschool children. The effects of child characteristics, parenting behaviors and teacher- child relationships. School Psychology International, 29(5), 590- 605.

- Simpkins, S. D., & Parke, R. D. (2001). The Relations between Parental Friendships and Children’s Friendships: Self- Reports and Observational Analysis. Child Development 72(2), 569–582.

- Spivak, A. L., & Howes, C. (2011). Social and relational factors in early education and prosocial actions of children of diverse ethnocultural communities. Merrill- Palmer Quarterly, 57(1), 1- 24.

- Stanton- Chapman, T. L. (2015). Promoting positive peer interactions in the preschool classroom: The role and the responsibility of the teacher in supporting children’s sociodramatic play. Early Childhood Education Journal, 43, 99- 107.

- White, K. J., & Kistner, J. (1992). The influence of teacher feedback on young children’s peer preferences and perceptions. Developmental Psychology, 28(5), 933- 940.

- Yang, O. S. (2000). Guiding children’s verbal plan and evaluation during free play: An application of Vygotsky’s genetic epistemology to the early childhood classroom. Early Childhood Education, 28(1), 3- 10.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

14 January 2019

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-052-5

Publisher

Future Academy

Volume

53

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-812

Subjects

Education, educational psychology, counselling psychology

Cite this article as:

Şendil, Ç. Ö. (2019). The Perspectives Of Teachers And Mothers On Peer Relations Of Preschoolers. In Z. Bekirogullari, M. Y. Minas, & R. X. Thambusamy (Eds.), ICEEPSY 2018: Education and Educational Psychology, vol 53. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 211-223). Future Academy. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2019.01.21