Abstract

Corporate reputation (CR) research has received a great deal of attention from scholars in different fields in explaining the positive outcomes of organisational achievement such as increased firm performance (FP). Since CR is created and implemented predominantly by the behaviour and performance of the leaders of that organisation, this study investigates the impact of CR perceptions of middle and top managers on FP. Although the relationship between CR and FP has been documented extensively, the current study differentiates itself by focusing on the reputation perceived by managers or leaders of the firms and its impact on the qualitative and quantitave performance Firms located around Kocaeli, operating in manufacturing industry were surveyed and a total of 181 questionnaires were used to test the predicted relationships. The results of the study indicate that vision and leadership, workplace environment, financial performance and product and services are positively related to quantitative performance. Vision and leadership, workplace environment, product and services are also positively associated with qualitative performance. The study is ended with conclusion and suggestions, study limitations, and directions for future research.

Keywords: Corporate reputationquantitative performancequalitative performance

Introduction

The resource-based view (RBV), authors such as Wernerfelt (1984) & Barney (1991) proposed that the crucial research question today concerns what kinds of corporate resources lead to sustainable competitive advantages or superior firm performance. Following these arguments, assets that are rare, firm-specific, and difficult to imitate or substitute have been considered as critical resources that enhance performance. Hall (1993; p.616) viewed a firm’s reputation as the most important intangible asset enhancing its performance because it is the “product of years of demonstrated superior competence, and is a fragile resource; it takes time to create, it cannot be bought, and it can be damaged easily”. Its rareness, uniqueness, and social complexity, makes it difficult to imitate, and thus reputation can explain the performance differences among organizations (Barney, 1991; Peteraf, 1993).

Similarly, Fombrun & Shanley (1990) consider good reputation as a strategic asset that can create an intangible obstacle that lesser rivals will have tough time overcoming. Reputation represents an intangible asset that is very difficult to copy, that has been created on the basis of former events and activities of companies (Fombrun & van Riel, 1997). It is a valuable intangible resource that can create market entry barriers, foster customer retention, and thus strengthen competitive advantages (Adeosun, Odetoyinbo & Olaseinde, 2013; p.221). There are also many empirical evidence that confirms that it enhance firm performance (Dunbar & Schwalbach, 2000; Kotha, Rajgopal & Rindova, 2001; Roberts & Dowling, 2002; Carmeli & Tishler, 2006). In line with the literature, this paper also argues that corporate reputation (CR) significantly affects firm performance (FP). It concludes with the recommendations with respect to analysis results and suggestions for future studies.

Literature Review and Theoretical Framework

Corporate Reputation

The last four decades have witnessed significant growth in interest in the subject of CR among academics and practitioners. However, there is no generally agreed definition of the concept since it contains a complex nature. Fombrun & Rindova (1996) in their cross-disciplinary literature review indicated that this ambiguity is the result of perceptual glasses of different disciplines. Economists (Weigelt & Camerer, 1998), sociologists (Abrahamson & Fombrun, 1992), accounting researchers (Dufrene, Wadsworth, Bjorson & Little, 1998; Sveiby, 1997), strategists (Caves & Porter, 1977; Freeman, 1984) and organizational scholars (Meyer, 1982; Dutton & Dukerich, 1991) defined the term based on their disciplinary perspectives.

Fombrun, Gardberg, and Sever, J (2000, p. 242) state that CR is a “collective construct that describes the aggregate perceptions of multiple stakeholders about a company’s performance. Gotsi & Wilson (2001) also consider reputation can be defined in terms of its perceptual nature and defined CR as “a stakeholder’s overall evaluation of a company over time. This evaluation is based on the stakeholder’s direct experiences with the company, any other form of communication and symbolism that provides information about the firm’s actions and/or a comparison with the actions of other leading rivals” (Gotsi & Wilson, 2001, p. 25). According to Wartick (1992, p. 34) CR is “the aggregation of a single stakeholder’s perceptions of how well organizational responses are meeting the demands and expectations of many organizational stakeholders”.

A good reputation can create several benefits such as enabling firms to charge premium prices; reducing firm costs and employee turnover; attracting applicants, investors and customers; increasing repurchases, customer retention and profitability; and creating competitive barriers (Fombrun & Shanley, 1990; Roberts & Dowling, 2002; Eberl & Schwaiger, 2005; Walker, 2010). It is generally concluded that employees prefer to work for highly reputed firms (Eberl & Schwaiger, 2005) and thus the firm take the advantage of recruiting and retaining a competent work force with less remuneration (Greyser 1999; Roberts & Dowling, 2002; Eberl &Schwaiger, 2005). The reputable company is likely to achieve strong competitive advantage, create competitive barriers, and enhance stock market performance as well as performance values on other measures (Fombrun, 1996; Iwu-Egwuonwu, 2011).

A variety of CR scales have been created but the most familiar is probably the Reputation Quotient (RQ) developed by Fombrun. The RQ measure includes 20 items relating products and services, emotional appeal, financial performance, social responsibility, vision and leadership, and workplace environment. Products and services dimension includes items that inquire quality, value, reliability perceptions of corporation’s products and services. Emotional appeal assesses how much the corporation is loved, appreciated, and respected. Financial performance consists of the perceptions of the monetary strength of the company including the expectations of the company, its risk and profitability perceptions.

Social responsibility measures whether stakeholders feel the company is a responsible citizen that supports good causes and demonstrates accountability to the environment and community. Vision and leadership refers stakeholders’ feeling that the company has a clear vision for the future, effective leadership, and the capability to recognize and seize market opportunities. The vision that is clearly articulated and practiced by corporate leaders provides stakeholders with a sense of purpose and direction, which inspires public confidence and positive evaluation. Work environment refers to whether stakeholders believe the company is well managed, has a good workforce, and is a good place to work (Fombrun, et al., 2000). The current study used the above six dimension of RQ since covers a variety of stakeholders perceptions and establish its empirical validity and reliability through cross cultural studies.

Corporate Reputation and Firm Performance

Considerable efforts have been devoted to explore the relationship between firms’ reputations and their financial performance and concluded a positive reputation performance relationship. For instance Roberts and Dowling (2002) using a a sample from 1984-1998 of Fortune’s report of America’s Most Admired Corporations question if a good reputation allows a firm to achieve superior profit outcomes over time. They found that firms with superior corporate reputations were more able to sustain superior profitability. Kotha et al. (2001) using a sample of Top-50 pure Internet firms also investigate the relationship among three types of reputation building activities including marketing investments, reputation borrowing, and media exposure and firm performance. According to the results of the study, reputation building activities may be one of the key determinants of competitive success.

Morover, Dunbar, & Schwalbach (2000) explore the relationship between CR and FP of 63 German firms from the survey by Manager Magazine that is similar to Fortune magazine in the years between 1988 and 1998. They find that large firm size and greater ownership concentration have a significant impact on CR which in turn positively impact overall financial performance. Similarly, Carmeli & Tishler (2006) investigated the perceived CR and its impact on FP. The results demonstrate that the impact of reputation on financial performance is mediated by firm’s growth and market share whereas the relation between product/services quality and reputation is mediated by customer satisfaction.

Sanchez & Sotorrio (2007) explored the relationship between CR and FP of the 100 most prestigious companies operating in Spain in 2004 and found a strong and nonlinear relationship between CR and FP. Ansong & Agyemang (2016) via data from 423 SMEs also documented a significant positive association between CR and FP by controlling for firm specific variables such as firm age, firm size, owner/manager’s age, leverage and access to capital. Chung, Eneroth & Schneeweis, (1999) research affirms the empirical evidence that firms that are highly ranked in reputation outperformed firms that were ranked low on reputation. Wang & Smith (2008) report that firms with high reputation had an average market value premium of $1.3 billion. Finally, Tan (2007) found CR is positively associated with both superior total sales and superior earnings quality in Chinese public companies.

The literature review leads to conclusion that CR certainly correlate with FP. However, there are some researchers that claim financial performance is more likely to affect CR, rather than vice versa. For instance, using a dataset of Danish firms, Rose & Thomsen (2004) investigate the relationship between CR and financial performance and conclude that reputation did not enhance financial performance, whereas financial performance had a positive impact on reputation. In addition, the authors suggest that past profitability influences a firm’s overall corporate reputation, which in turn influences future financial performance. According to Waddock & Graves (1997) the relation between CR and financial performance is synergistic—that CR is both a predictor and a consequence of financial performance, thereby forming a virtuous circle. Similarly, Sabate, & Puente (2003) stated that the relation between CR and financial performance reflect the two-way relationship. For instance, financially successful companies can afford to spend more money on social issues that contributes the reputation, but these same initiatives stimulate financial performance (Surroca, Trib, & Waddock, 2010).

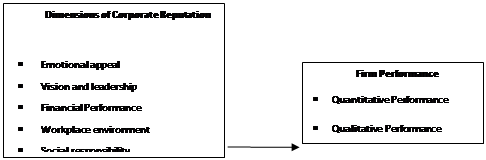

Although the relationship between CR and FP has been documented extensively, the current study differentiates itself by focusing on the reputation perceived by managers or leaders of the firms and its impact on the qualitative and quantitave performance. The reputation perception of internal stakeholders is critical because the greatest reputation leverage can be achieved through them (Fombrun et al., 2000), as they shape external reputation. When the organization concentrates in managing and monitoring CR dimensions including products and services, emotional appeal, financial performance, social responsibility, vision and leadership, and workplace environment, the qualitative and quantitave performance of the firms is influenced positively. In addition, managers views of the reputation can be transferred from one stakeholder to another (e.g. manager to employee; employee to customer) and more likely affect both the FP and CR. In other words the relationship between CR and FP is mutually dependent and also affected by the perceptions of various stakeholders.

Research Method

Research Design

This study investigates the impact of CR perceptions of middle and top managers on FP. The positive perception of CR dimensions is predicted to increase both quantitative and qualitative performance of the firm. Accordingly the following hypotheses are developed.

H1: The positive perception of “emotional appeal” will be positively associated with quantitative performance.

H2: The positive perception of “vision and leadership” will be positively associated with quantitative performance.

H3: The positive perception of “social responsibility” will be positively associated with quantitative performance.

H4: The positive perception of “workplace environment” will be positively associated with quantitative performance.

H5: The positive perception of “financial performance” will be positively associated with quantitative performance.

H6: The positive perception of “product and services” will be positively associated with quantitative performance.

H7: The positive perception of “emotional appeal” will be positively associated with qualitative performance.

H8: The positive perception of “financial performance” will be positively associated with qualitative performance.

H9: The positive perception of “vision and leadership” will be positively associated with qualitative performance.

H10: The positive perception of “social responsibility” will be positively associated with qualitative performance.

H11: The positive perception of “workplace environment” will be positively associated with qualitative performance.

H12: The positive perception of “product and services” will be positively associated with qualitative performance.

Besides, the proposed conceptual model guiding this research is depicted in Fig.

Scales and Sampling

The aim of this paper is to describe and analyze the mutual relationships among dimensions of corporate reputation and firm performance. In order to empirically investigate the hypotheses, firms located around Kocaeli, operating in manufacturing industry were surveyed. Using the documents of Kocaeli Chamber of Commerce, 100 firms among 650 are identified as the target group of the research because of their availableness. Tools such as e-mail, letter and face to face interviews are used for gathering data from the managers -top, middle or first line managers. A total of 181 questionnaires among 48 firms have returned. The mean age of the participants is 28, 47; the proportion of men, 68%, and married 50, 8%. Of the participants, %48,1 have university educations and %19,3 have master education, %82,9 are first line managers, %11 are middle managers and %6,1 are top managers.

To test the above hypotheses, multi-item scales adopted from prior studies for the measurement of constructs were used. Corporate reputation was measured by 25 items adopted from the Reputation Quotient (RQ) developed by Fombrun and the market research firm Harris Interactive (HI). Corporate reputation scale was measured by 25 items developed from the study of Charles J. Fombrun and Reputation Institute (2000). The scale includes six dimensions including emotional appeal (3 items), financial performance (6 items), product and services (3 items), vision and leadership (3 items), workplace environment (5 items) and social responsibility (5 items). Quantitative performance scale includes 6 items and adapted from Lynch, Keller & Ozment, (2000) and Baker & Sinkula (1999). Qualitative performance scale includes 3 items adapted from Fuentes-Fuentes, Albacete-Sáez, and Lloréns-Montes, (2004) and Rahman & Bullock (2004). All items were rated using a 5-point scale ranging from 1 “Very strongly disagree” to 5 “Very strongly agree”.

Analysis and results

We used the partial least squares PLS-Graph 3.0 approach to path modelling to estimate the measurement and structural parameters in our structural equation model (SEM) (Chin, 1998; 2001). The reason for using this technique is that PLS method can operate under limited number of observations and more discrete or continuous variables. Therefore PLS method is an appropriate method for analysing operational applications. PLS is also a latent variable modelling technique that incorporates multiple dependent constructs and explicitly recognizes measurement error (Karimi, 2009). Also PLS is far less restrictive in its distributional assumption and PLS applies to situations where knowledge about the distribution of the latent variables is limited and requires the estimates to be more closely tied to the data compared to covariance structure analysis (Fornell & Cha, 1994). To assess the psychometric properties of the measurement instruments, we estimated a null model with no structural relationships. We evaluated reliability by means of composite scale reliability (CR) and average variance extracted (AVE). For all measures, PLS-based CR is well above the cut-off value of. 70, and AVE exceeds the. 50 cut-off value (see Table

In addition, we evaluated convergent validity by inspecting the standardized loadings of the measures on their respective constructs and found that all measures exhibit standardized loadings that exceed.60. We next assessed the discriminant validity of the measures. As suggested by Fornell & Larcker (1981) the AVE for each construct was greater than the squared latent factor correlations between pairs of constructs (see Table

Hypothesis Testing

We used PLS path modelling which allows for explicit estimation of latent variable (LV) scores, to estimate the main effects in our model (see Figure

Conclusion and Discussions

An organization is a sociological system that represents the community of persons and the behaviour of an organisation's members has a considerable impact on its operations and their outcomes. The members of the organisation have the ability to affect the impressions formed by members of external groups, such as customers, competitors, suppliers, investors, and media commentators (Dennis, 2001, p. 317). Since CR is created and implemented predominantly by the behaviour and performance of the leaders of that organisation, this study investigates the impact of CR perceptions of middle and top managers on FP. Besides quantitative indicators, the study also includes qualitative ones to measure performance.

The results of the study indicate that vision and leadership, workplace environment, product and services are positively associated with qualitative and quantitative performance. First, vision and leadership can have a wide-ranging impact on internal and external stakeholders from poor communication to lack of integrity. Leaders who are effective in internal and external communications are successfully able to meet expectations of both internal and external stakeholders such as shareholders, customers, government, employees and communities to ensure long-term benefits for all. Second, product and services presents a logical relationship between CR and FP. An increase in the quality, value, reliability perceptions of corporation’s products and services will lead to improved customer perceptions which in turn will increase the likelihood of repeat purchases. The customer perspective relates to the quantitative performance whereas the employee perspective relates to qualitative performance that represents the degree to which employees are prepared to rethink and innovate business processes.

Thirdly, numerous researches confirm that working environment has a positive effect on moral, dedication and productivity of the employees (Çekmecelioğlu, 2005; Özbağ, 2014) and thus the overall performance of the firm. Efficient planning of work and organizational structure, effective communication and reward management strategy, employee involvement in decision-making, less organizational bureaucracy, trust in colleagues and supervisors are significant factors that enhance employee productivity. As people are the most valuable resource of an organization, and that improvement in some of the dimensions of working environment make a difference to individual performance which turn in turn boosts firm performance.

The results of the study should be interpreted in view of some limitations. Self-report surveys were used to measure the results which could be limited by a socially desirable response. In addition, the generalizability of sampling is another limitation of this study because the study was conducted in a specific cultural context, Turkish firms. Since, culture influences perceptions of people, the relationship between culture and perceptual structure of corporate reputation can be investigated as future study suggestion. Finally, there are many other mediating and moderating variables that impact the relationship between reputation and performance. Therefore, future studies could explore other variables such as organizational culture, ethical leadership, psychological empowerment, creativity climate, satisfaction and commitment to clarify the relationship between CR and FP.

References

- Abrahamson, E., & Fombrun, C.J. (1992). Forging the Iron Cage: Inter Organizational Networks and the Production of Macro-Culture, Journal of Management Studies, 29, 175-194.

- Adeosun, S.H, Odetoyinbo, A., & Olaseinde, W. (2013). The Broadcast World: Editing, Production and Management, Abeokuta: Primus Prints and Communications.

- Ansong, A., & Agyemang, O. S. (2016). Firm reputation and financial performance of SMEs: The Ghanaian perspective, EuroMed J. of Management, 1, 237–251.

- Barney, J. (1991). Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage, Journal of Management, 17 (1), 99-120.

- Baker, W.E., & Sinkula, J.M. (1999). The synergistic effects of market orientation and learning orientation on organizational performance, Journal of Academy of Marketing Science, 27(4), 411-427.

- Carmeli, A., & Tishler A. (2006). Perceived Organizational Reputation and Organizational Performance. An Empirical Investigation of Industrial Enterprises, Corporate Reputation Review, 8(1), 13-30.

- Caves, R.E., & Porter, M.E. (1977). From Entry Barriers to Mobility Barriers, Quarterly Journal of Economics, 91, 421‐34.

- Chin, W.W. (1998). The Partial Least Squares Approach for Structural Equation Modeling. In GA Marcoulides (ed.), Modern Methods for Business Research, pp.295–336. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, London.

- Chin, W. W. (2001). PLS – Graph User’s Guide Version 3.0., Houston, TX: Soft Modeling Inc.

- Chung, S.Y., Eneroth, K. & Schneeweis, T. (1999). Corporate Reputation and Investment Performance: The UK and US Experience, SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=167629 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.167629

- Çekmecelioğlu, H. G. (2005). Örgüt İkliminin İş Tatmini ve İşten Ayrılma Niyeti Üzerindeki Etkisi: Bir Araştırma, Cumhuriyet Üniversitesi İktisadi ve İdari Bilimler Fakültesi Dergisi, 6 (2), 23-39.

- Dennis, B.B. (2001). Relationships between Personal and Corporate Reputation, European Journal of Marketing, 35(4), 316-334.

- Dufrene, U., Wadsworth, F.H., Bjorson, C. & Little, E. (1998). Evaluating tangible asset investment: the value of cross functional teams, Management Research News, 21(10), 1-13.

- Dunbar, R.L.M. & Schwalbach, J. (2000). Corporate Reputation and Performance in Germany, Working Paper,1-15.

- Dutton, J.E. & Dukerich, J.M. (1991). Keeping an eye on the mirror: image and identity in organizational adaptation, Academy of Management Journal, 34, 517‐54.

- Eberl, M. & Schwaiger, M. (2005). Corporate Reputation: Disentangling the Effects on Financial Performance, European Journal of Marketing, 39, 838–854.

- Fuentes-Fuentes, M.M., Albacete-Sáez, C.A., & Lloréns-Montes, F.J. (2004). The impact of environmental characteristics on TQM principles and organizational performance, Omega, 32(6), 425-442.

- Fombrun, C. J., & Shanley, M. (1990). What’s in a name? Reputation building and corporate strategy. Academy of Management Journal, 33: 233-258.

- Fombrun, C.J. (1996). Reputation: Realizing Value from Corporate Image, Boston, MA.: Harvard Business School Press.

- Fombrum, C.J., & Van Riel, C.B.M. (1997). The Reputation Landscape. Corporate Reputation Review, 5-13.

- Fombrun, C. J., & Shanley, M. (1990). What’s in a name? Reputation Building and Corporate Strategy, Academy of Management Journal, 33 (2), 233-258.

- Fombrun, C.J. & Rindova, V. (1996). Who’s Tops and Who Decides? The Social Construction of Corporate Reputations, New York University, Stern School of Business, Working Paper.

- Fombrun, C.J., Gardberg, N.A. and Sever, J.M. (2000). The reputation quotient: a multiple stakeholder measure of corporate reputation. Journal of Brand Management, 7(4), 241–255.

- Fornell, C. & Cha, J. (1994). Partial Least Squares, Advanced Methods of Marketing Research, 407, 52-78.

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error, Journal of Marketing Research, 18, 39–50.

- Freeman, R.E. (1984). Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach, Pitman Press, Boston, MA.

- Greyser, S.A., (1999). Advancing and Enhancing Corporate Reputation, Corporate Communications: An International Journal, 4 , 177–181.

- Gotsi, M. & Wilson, A. (2001). Corporate reputation: Seeking a definition. Corporate Communications, 6(1), 24-30.

- Hall, R. (1993). A Framework Linking Intangible Resources and Capabilities to Sustainable Competitive Advantage, Strategic Management Journal, 14(8), 607-618.

- Iwu-Egwuonwu, P.C. (2011). Corporate Reputation & Firm Performance: Empirical Literature Evidence, International Journal of Business and Management, 6(4), 197-204.

- Karimi, J. (2009). Emotional Labor And Psychological Distress: Testing The Mediatory Role Of Work-Family Conflict, European Journal Of Social Sciences, 11(4), 584-598.

- Kotha, S., Rajgopal, S., & Rindova, V. (2001). Reputation building and performance: an empirical analysis of the top-50 pure internet firms, European Management Journal, 19, 571–586.

- Lynch, D.F., Keller, S.B. & Ozment, J. (2000). The effects of logistics capabilities and strategy on firm performance, Journal of Business Logistics, 21(2), 47-67.

- Meyer, A. (1982). Adapting to environmental jolts, Administrative Science Quarterly, 27, 515–537.

- Peteraf, M. (1993). The Cornerstones of Competitive Advantage: A Resource-Based View, Strategic Management Journal, 14(3), 179-191.

- Roberts, P.W., & Dowling, G.R., (2002). Corporate Reputation and Sustained Superior Financial Performance, Strategic Management Journal, 23, 1077–1093.

- Rahman, S.U. & Bullock, P. (2005). Soft TQM, hard TQM, and organisational performance relationships: an empirical investigation, Omega, 33(1), 73-83.

- Rose, C., Thomsen, S. (2004). The Impact of Corporate Reputation on Performance: Some Danish Evidence, European Management Journal, 22, 201-210.

- Sabate, J.M., & Puente, E. (2003). Empirical Analysis of the Relationship Between Corporate Reputation and Financial Performance:A Survey of the Literature, Corporate Reputation Review, 6, 161-177.

- Sanchez, J.L.F., & L.L., Sotorrio, 2007. The Creation of Value through Corporate Reputation, Journal of Business Ethics, 76, 335–346.

- Surroca, J., Trib, J. A., & Waddock, S. (2010). Corporate responsibility and financial performance: The role of intangible resources, Strategic Management Journal, 31, 463–490.

- Sveiby, K.E. (1997). The New Organizational Wealth: Managing and Measuring Knowledge‐based Assets, Berrett‐Koehler, San Francisco, CA.

- Tan, H. (2007). Does the reputation matter? Corporate reputation and earnings quality, working paper, China Southwestern University of Finance and Economics.

- Özbağ, K. G. (2014). A Research on the Relationships among Perceived Organizational Climate, Individual Creativity and Organizational Innovation, İşletme Araştırmaları Dergisi, 6(1), 21-31.

- Waddock, S., Bodwell, C. & Graves, S. (2002). Responsibility: The new business imperative, Academy of Management Perspectives, 16(2), 132-148.

- Wang, K., & L. Smith. (2008). Does corporate reputation translate into higher market value? Working paper, Texas Southern University.

- Walker, K., (2010). A Systematic Review of the Corporate Reputation Literature: Definition, Measurement, and Theory, Corporate Reputation Review, 12, 357–387.

- Wartick, S.L. (1992). The relationship between intense media exposure and change in corporate reputation, Business & Society, 31(1), 33–49.

- Weigelt, K., & Camerer, C. (1988). Reputation and corporate strategy: a review of recent theories and applications, Strategic Management Journal, 9(5), 443‐54.

- Wernerfelt, B. (1984). A Resource-Based View of the Firm, Strategic Management Journal, 5(2), 171-180.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

28 January 2019

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-053-2

Publisher

Future Academy

Volume

54

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-884

Subjects

Business, Innovation, Strategic management, Leadership, Technology, Sustainability

Cite this article as:

Kaya Özbağ, G., & Gündüz Çekmecelioğlu, H. (2019). Examining The Effects Of Dimensions Of Corporate Reputation On Firm Performance. In M. Özşahin, & T. Hıdırlar (Eds.), New Challenges in Leadership and Technology Management, vol 54. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 270-280). Future Academy. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2019.01.02.24