Abstract

The aim of this article is to analyze the main indicators specific to the quantitative and qualitative employment, in Romania, in the period following the adoption of the Europe 2020 strategy, in order to identify some actions needed to be taken so that the quality of employment improves and has positive consequences on the well-being of Europeans. The results of the study highlight that Romania, between 2010 and 2016, made little progress in terms of employment, both quantitative and qualitative, and show the existence of large gaps between Romania, as an EU member state, and EU-28 average. In order to achieve the Europe 2020 Strategy objectives in terms of employment and poverty, it is highly necessary that low quality jobs and poor workers benefit the most from actions to support the diverse dimensions of job. Taking into account that better education improves employability and quality of employment and more and better jobs can in turn contribute to economic and social performance, education and training has to become a strategic priority for any country that aims to become a smart, sustainable and inclusive economy.

Keywords: Quality of employmentEuropean strategy; national strategylabour marketworking poverty

Introduction

It is widely recognised that “employment contributes to economic performance, quality of life and social inclusion, making it a cornerstone of socioeconomic development and well-being” (EU, 2017a, p. 26). Moreover, it is underlined that only high quality jobs are drivers of development and matter for development (ILO, 2014).

Employment is an important element of the social and economic development of workers and “provides them with a sense of identity, but it may also be associated with risks for health and well-being” (UN, 2015a). Thus, the quality of employment may play an important role, both at society and individual level, being a key factor that enhances sustainability of employment.

The importance of quality of employment is highlighted through including it (directly or indirectly) in the international and national strategies as a key-objective.

Quality of employment is a multidimensional concept and complex to measure (UN, 2015a; EU, 2017d; Bodea & Herman, 2014), its definition and components depending on whether “quality of employment is assessed from the perspective of the society, the corporation or the individual” (UN, 2015a). The Expert Group on Measuring Quality of Employment (UN, 2015a) adopts the individual’s perspective on quality of employment, taking into account that employment provides income as well as and social security, identity and self-esteem. Thus, quality of employment is defined based on all the aspects of employment that may affect the well-being of employed persons. According to UN (2015a), quality of employment is measured based on seven dimensions: safety and ethics of employment, income and benefits from employment, working time and work-life balance, security of employment and social protection, social dialogue, skills development and training and employment-related relationships and work motivation.

Eurofound (2017a), based on seven indices of job quality (physical environment, work intensity, working time quality, social environment, skills and discretion, prospects and earnings) shows that, at EU-28 level, one out of five workers holds a poor quality job, and structural inequalities and differences in job quality have been recorded in European workplaces. The structure of employment can affect the quality of job. Thus, more favourable job quality is reported by employees on indefinite contracts and employers (self-employed with employees) than the self- employed without employees and workers on temporary contracts. (Eurofound, 2017a).

According to World of Work Report 2014 (ILO, 2014),

In this context,

Strategic objectives for increasing employment and reducing poverty in the context of the Europe2020 Strategy

According to EC (2010a), through the Europe 2020 Strategy, the European Union aims “to become a smart, sustainable and inclusive economy delivering high levels of employment, productivity and social cohesion”. The Europe 2020 Strategy puts forward three mutually reinforcing priorities: smart growth (developing an economy based on knowledge and innovation), sustainable growth (promoting a more resource efficient, greener and more competitive economy) and inclusive growth (fostering a high-employment economy delivering social and territorial cohesion). In this Strategy,

The EU target for inclusive growth stipulated in Europe 2020"Strategy (Table

In order to raise effectiveness in implementing the strategy, the individual member states can support themselves by creating their own policies such as: action plans and defining goals and short-term, mid-term and long-term actions; periodic reviews of the strategy implementation regarding realization of its objectives (Stec & Grzebyk, 2018).

Taking into account that the EU will not achieve its goals if the individual member states do not pursue them (Stec & Grzebyk, 2018), Romania, as a EU member state, adapted the 2020 Europe strategy to its specific situation (the historical evolution of the annual growth rhythm of employment rate, the economic growth potential and the demographic evolution forecasted for the next decade) and set through the National Reform Program (G.R., 2011) the following national targets for inclusive growth: an employment rate (aged 20-64) of 70% by 2020, 5 percentage points (p.p) below the EU target; reducing school drop-out rates to 11.3% (above the EU target of 10%), increasing the rate of population aged 30-34 years that graduates a form of tertiary education to 26.7% (below the EU target of 40%) and reducing the population at risk of poverty or social exclusion by 580,000 persons.

Although Romania has made some progress in terms of these four headline targets, the current situation (the year 2016) highlights real gaps in the objectives of both Romania and the EU (see Table

As regards the reduction of

As for

The strategy’s inclusive growth implies that the employment target should be closely interlinked with the other strategy goals on education and poverty and social exclusion and also with research and development target. Better educational levels increase employability and quality of employment (Barbulescu, 2015) and more and better jobs can in turn contribute to economic performance and poverty reduction. Moreover, “boosting R&D capacity and innovation could improve competitiveness and thus contribute to job creation” (EU, 2017a). All these strategic objectives have to be interlinked taking into account that the essential measure of the inclusiveness of a society’s growth model is given by the extent to which it produces broad gains in living standards before social transfers (WEF, 2015).

Quantity versus quality in employment: a real challenge for Romania

In order to highlight the real progress in terms of employment target, at the level of both EU and Romania, as a member state, it is necessary to analyze the contextual indicators of the characteristics of the labour market, and the quantitative, structural and qualitative indicators of employment.

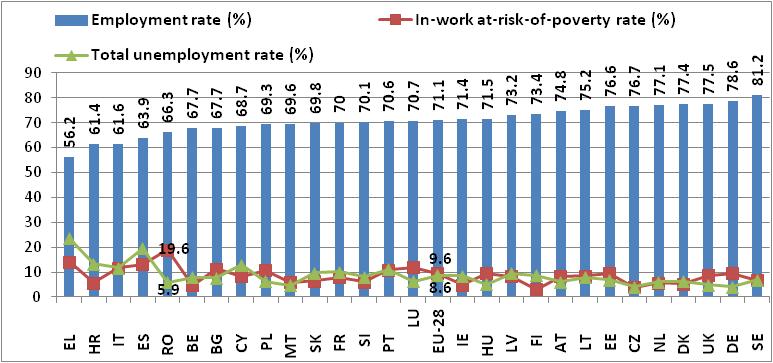

According to statistical data (Figure

A real socio-economic challenge of the labour market and the whole economy is

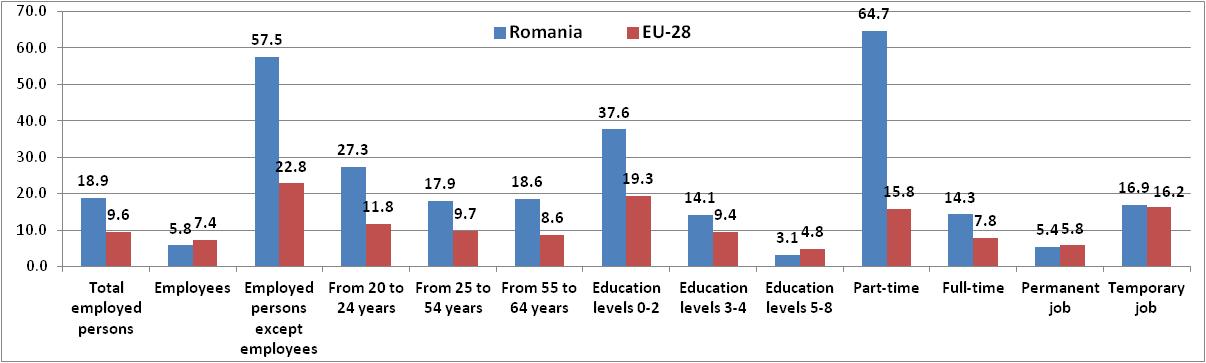

According to data illustrated in Figure

Based on the

Despite the fact that Romania recorded a very low share of

Taking into consideration that “a low wage is the most straightforward link to in-work poverty” (Eurofound, 2017b, p. 7), in Romania, the high level of in-work poverty can be explained by a high level of low-wage earners (as % of all employees). There is a higher share of low-wage earners in total employees in Romania than in EU-28 (24.4% related to 17.19%, Table

Corroborating these results (high working poverty and high vulnerable employment) with the low level of labour productivity, slightly over half of the EU-28 average, 61.6% of EU-28 (of 100%), it is proved that, in Romania, there is a

Figure

From the perspective of “skills development and training” dimension of quality of employment (according to UN, 2015a), statistical data regarding

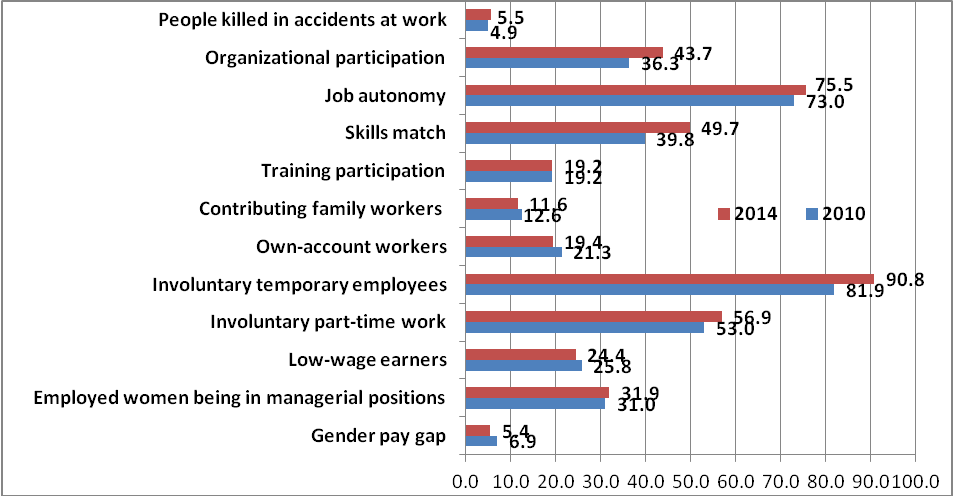

In order to emphasise the progress in quality of employment made by Romania, in 2010-2014 period, we have analysed twelve indicators (gender pay gap, employed women being in managerial positions, low-wage earners, involuntary part-time work, involuntary temporary employees, own-account workers, contributing family workers, training participation, skills match, job autonomy, organizational participation and people killed in accidents at work) related to seven quality of employment dimensions according to UN (2015a). Statistical data (Table

A comparative analysis of the current level of the quality of employment indicators (for the year 2014), illustrates negative gaps between Romania and EU-28 average (see Table

The main active measures to improve quality of employment in Romania

Moreover, the share of training, as a component of active labour market policies, is very low (less than 1%), emphasising the fact that there is an insufficient support both for transition between unemployment and employment and for helping to keep people integrated into the labour market through the accumulation of required skills. In Romania, adult participation in learning (% of population aged 25 to 64) is very low (only 1.2% in 2016), much below the EU-28 average of 10.8% (Eurostat Database, 2018).

Taking into consideration that a high level of education and training is a key driver of improving quality of employment, a better education and training of people is considered a European and national strategic objective. Romania, through the

Nevertheless, in Romania, public expenditure on education represents only 3.1% of GDP (in 2015) related to 4.8% at EU level. Furthermore, annual expenditure on educational institutions per pupil/student (euro) is very low (1142 euro against 7509.3 euro). All these statistical data prove, on the one hand, that Romanian education is underfinanced, and, on the other hand, the need to increase spending in education in order to “improve educational outcomes, support human capital development and economic growth” (EU, 2017c).

Conclusions

The empirical research and EU Reports show that progress in employment rate, as Europe 2020 strategy target, is not always associated with progress in quality of employment. This study has shed light on the main challenges of quality of employment in Romania, as an EU member stat, in the period following the adoption of the Europe 2020strategy.

The results of the study highlight that Romania, between 2010 and 2016, made little progress in terms of employment, both quantitative and qualitative, and indicates the existence of large gaps between Romania and EU-28 average. A major issue for Romania is the persistence of a very high level of working poverty that is mainly associated with a high level of vulnerable employment, low level of labour productivity, emphasising also a deficit in job quality. Moreover, we find that Romania is characterized by both a low level of labour market policies and an inefficient structure of them, fact that requires taking some measures for increasing the effectiveness of labour market policies.

Based on the fact that better education can improve employability and quality of employment and more and better jobs can in turn contribute to economic and social performance, education and training has to become a strategic priority for any country that aims to become a smart, sustainable and inclusive economy. In order to achieve the Europe 2020 Strategy objectives in terms of employment and poverty, it is absolutely necessary for low quality jobs and poor workers to benefit most from actions that support the diverse dimensions of job. Improving job quality and working conditions continues to be a significant goal in European policies, being a cross-cutting issue that influences, but at the same time it is influenced by many other European policies (Eurofound, 2017a).

References

- Andreß, H.-J., & Lohmann, H. (2008). The working poor in Europe. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Barbulescu, A. (2015). Quality culture in the Romanian higher education. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 191, 1923-1927.

- Bodea, G., & Herman, E. (2014). Factors behind working poverty in Romania. Procedia Economics and Finance, 15, 711-720.

- Crettaz, E., & Bonoli, G. (2010). Why are some workers poor? The mechanisms that produce working poverty in a comparative perspective. REC-WP 12/2010. Retrieved from https://www.era.lib.ed.ac.uk/bitstream/1842/3985/1/REC-WP_ 1210_Crettaz_Bonoli.pdf

- Davoine, L., Erhel, C., & Guergoat-Lariviere, M. (2008). Monitoring Quality in Work: European Employment Strategy Indicators and Beyond. International Labour Review, 147 (2-3), 163-198.

- EAPN - European Anti-Poverty Network. (2013). Working and Poor. EAPN Position Paper on In-Work Poverty. Retrieved from http://www.eapn.eu/images/stories/docs/EAPN-position-papers-and-reports/2013-EAPN-in-work-poverty-position-paper-web.pdf

- EC- European Commission (2010a.) EUROPE 2020. A strategy for smart, sustainable and inclusive growth. Retrieved from http://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=COM:2010:2020: FIN:EN:PDF

- EC (2010b). An Agenda for new skills and jobs: A European contribution towards full employment. Retrieved from http://www.cedefop.europa.eu/en/news-and-press/news/agenda-new-skills-and-jobs-european-contribution-towards-full-employment

- EU- European Union. (2017a). Smarter, greener, more inclusive? Indicators to support the Europe 2020 strategy. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union

- EU (2017b). Social Scoreboard 2017: Headline indicators: descriptions and highlights. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union

- EU (2017c). Education and Training Monitor 2017 Romania. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union

- EU (2017d). The Employment and Social Developments in Europe 2017 review. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union

- Eurofound (2017a). Sixth European Working Conditions Survey – Overview report (2017 update). Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union

- Eurofound (2017b). In-work poverty in the EU. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union

- Eurostat Database (2018). Retrieved from http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/data/database

- Fraser, N., Gutierrez, R., & Pena-Casas, R. (Eds.). (2011). Working Poverty in Europe. A Comparative Approach. Bakingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- G.R. - Government of Romania (2011). National Reform Program. Retrieved from http://ec.europa.eu/europe2020/pdf/nrp/nrp_romania_en.pdf

- G.R. (2015). The National Strategy for Tertiary Education 2015-2020. Retrieved from https://ec.europa.eu/education/compendium/national-strategy-tertiary-education-2015-2020_en

- G.R. (2016) National education and training strategy for the period 2016-2020. Retrieved from https://www.edu.ro/sites/default/files/_fi%C8%99iere/Minister/2016/strategii/Strategia_VET%2027%2004%202016.pdf

- Herman, E., & Georgescu, M. A. (2012). Employment strategy for poverty reduction. A Romanian perspective. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 58, 406-415.

- Herman, E. (2014). Working Poverty in the European Union and its Main Determinants: an Empirical Analysis. Engineering Economics, 25 (4), 427-436.

- Herman, E. (2016). Productive Employment in Romania: A Major Challenge to the Integration into the European Union. Amfiteatru Economic, 18 (42), 335-350.

- Heyes, J. (2013). Flexicurity in Crisis: European Labour Market Policies in a Time of Austerity. European Journal of Industrial Relations, 19(1), 71-86.

- ILO (2014). World of Work Report 2014: Developing with jobs. Geneva: International Labour Office.

- ILO (2016a). ILO report of 14 November 2016 on non-standard employment around the world. Retrieved from http://www.ilo.org/global/publications/books/WCMS_534326/lang--en/index.htm.

- ILO (2016b). World Employment and Social Outlook: Transforming jobs to end poverty. Geneva: International Labour Office.

- Pena-Casas, R. & Latta, M., 2004. Working Poor in the European Union. European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions, Dublin. Retrieved from http://www.eurofound.europa.eu/pubdocs/2004/ 67/en/1/ef0467en.pdf

- Stec, M., & Grzebyk, M. (2018). The implementation of the Strategy Europe 2020 objectives in European Union countries: The concept analysis and statistical evaluation. Quality & Quantity, 52(1), 119-133.

- UN- United Nations (2015a). Measuring Quality of Employment a Statistical Framework. ECE/CES/40 New York and Geneva. Retrieved from http://www.unece.org/fileadmin/DAM/stats/publications/2015/ECE_CES_40.pdf

- UN (2015b). Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Retrieved from https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/post2015/transformingourworld/publication

- WEF-World Economic Forum (2015). The inclusive growth and development Report 2015. Retrieved from http://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_Forum_IncGrwth.pdf

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

28 January 2019

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-053-2

Publisher

Future Academy

Volume

54

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-884

Subjects

Business, Innovation, Strategic management, Leadership, Technology, Sustainability

Cite this article as:

Herman, E. (2019). Strategic Issues For The Qualitative Improvement Of Romanian Employment: An Empirical Analysis. In M. Özşahin, & T. Hıdırlar (Eds.), New Challenges in Leadership and Technology Management, vol 54. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 111-122). Future Academy. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2019.01.02.10