Abstract

This paper reports a study which aims to develop a legal and policy frameworks to overcome public information lock up in Malaysia. Public information lock up refers to the presence of the laws and policies which impede the citizens’ right to receive public sector information. Previous studies have identified public information lock up arising from colonial-origin legislations and post-colonial legislations which impede citizens’ right to receive information classified as sensitive, prohibited or non-accessible by the Government. The legal impediments have not been fully addressed in Malaysia, either through constitutional protection or sui generis law on the right to information. Hence, the need for an appropriate legal and policy frameworks to be developed. This study compared the laws and policies on citizens’ right to information in the UK, Canada and New Zealand in order to identify the legal and policy measures to overcome public information lock up. A cross-sectional survey using a 5-point Likert scale was also conducted among 40 respondents from government agency, independent statutory body, civil society and academia. The findings of the survey help to provide an insight on the most appropriate legal and policy measures to overcome public information lock up in Malaysia. The legal and policy frameworks are suitable for adoption by legislatures and policy makers and can become a benchmark in pursuing the objective of overcoming public information lock up in Malaysia.

Keywords: Information lock upright to informationpublic sector informationlaw and policy

Introduction

This study focused on the legal impediments to citizens’ right to information in Malaysia in the form of public information lock up which impede the citizens’ right to receive information classified as sensitive, prohibited or non-accessible by the Government. Citizens have a right to information, which empowers the citizen with the right to know the truth and the right to seek, receive and impart public information (Mishra, 2013). The right to information is interlinked to other constitutional rights and is also regarded as precondition of the freedom of press and media (Peled & Rabin, 2011). Within the context of this study, ‘Public Sector Information’ refers to information produced or held by government or for government under a law or in connection with official function, business or affair. The term “Government” includes the Ministers, the government body/agency and the government employees at federal, states and local governments levels (Lor & Bitz, 2007).

The right to information protects the citizens’ right to know that their government acts fairly, lawfully, and accurately (Janssen, 2012). The right to information also confers on the citizen, the right to request to the Government to disclose the public information whereby the Government must comply with such requests (Legault, (2012). In making such request, a citizen does not need to show any legal or special interest in order to establish his or her right to public information (Legaspi v Civil Service Commission, 1987).

As far as Malaysia is concerned, review of literature also found that previous studies mostly report about the absence of constitutional and legislative protection for the right to information in Malaysia (see, Low, 2015; Muhamad Izwan, 2014, Commonwealth Initiative for Human Rights, 2011, Venkiteswaran, 2010). Several studies were also made on the Freedom of Information Enactment of the states of Selangor and Penang whereby these studies found that the enactments are subject to federal laws including those laws which impede citizens’ right to information (Bhatt, 2011, The Constitution Unit UCL, 2011). Despite the existence of legal impediments to citizens’ right to information, the previous studies did not develop a legal and policy frameworks to overcome public information lock up arising from a myriad of impeding laws currently in operation in this country.

As there is a lacuna, this study aims to develop a legal and policy frameworks to overcome public information lock up in Malaysia.

Problem Statement

While the Government has both the positive obligation to provide and the negative obligation not to impede citizens’ right to information, there is neither a constitutional guarantee nor a sui generis law that provides a formal, functioning system to respect, ensure, promote and protect the citizens’ right to receive public sector information in Malaysia. Further analysis reveals that, Malaysia inherits colonial-origin legislations (Sedition Act 1948 and Penal Code) as well as enacting new legislations (Official Secrets Act 1972; Printing Presses and Publications Act 1984; Computer Crimes Act 1997; Communications and Multimedia Act 1998; Copyright Act 1987) which impede citizens’ right to information (Amnesty International, 2015; Johan, 2013).

Though admittedly the legislations were put in place to protect public order and safety as well as national interests and security, in practice these legislations also impede to the citizens’ right to receive public sector information deemed necessary for the exercise of their democratic rights in accordance to participatory democracy principles (Floridia, 2013; Hilmer, 2010). Any person who receives information which are classified as sensitive, prohibited or non-accessible risks prosecution for espionage, or violation of secrecy, publication or intellectual property laws.

Public information lock up limits the ability of the citizens to question and hold to account the legislature, executive and judiciary (UNDP, 2006, Daruwala, 2003). Information lock up has adverse effect on the citizens’ ability to make informed decisions and affects the openness of a Government (Pradeep, 2012). Public information lock up is also regarded as pre-cursor of corruption as it reduces transparency and accountability of the Government. The information lock up also leads to public suspicion and destroys public trust in the government (Zausmer, 2011).

Due to the prevalence of public information lock up, there have been numerous calls by Malaysian civil society and distinguished members of community for the Government to recognize right to information as constitutional and legal right (Bhatt, 2010; Venkiteswaran, 2010; Fernandez, 2016). There is a high expectation among members of public for Malaysia to take appropriate legal and policy measures to overcome public information lock up. Civil rights activists from local non-governmental organizations urged for the right to information law which is consistent with international standards to be adopted and implemented as a matter of priority (Yong, 2016; Centre for Independent Journalism, 2007). The fact that most countries have already passed legislations to give effect to right to information, further heightened the citizens’ expectation for Malaysia to have similar legislation (The Malaysian Insider, 2014).

Research Questions

As the aim of this study is to develop a legal and policy frameworks to overcome public information lock up in Malaysia, there are two research questions which need to be answered in this study. Firstly, What are the legal and policy measures most appropriate to overcome public information lock up? And secondly, how should a legal and policy frameworks be developed to overcome public information lock up in Malaysia?

Purpose of the Study

The purpose of this study is to develop a legal and policy frameworks to overcome public information lock up in Malaysia.

Research Methods

Research Design

This study is classified as fundamental research since its aim is to develop a legal and policy frameworks to overcome public information lock up in Malaysia. This study is further classified as legal research as its research problem stems from the absence of constitutional protection and sui generis law for citizens’ right to information, apart from the presence of conflicting laws which impede citizens’ right to information in Malaysia. This study employs a mixed modes approach involving field work and library based research. A primary data was collected using survey questionnaires with 40 respondents.

Instruments

Survey questionnaires was used as an instrument to answer the first research question. The survey questionnaires are divided into seven separate sections. The first section (Part A) was designed with the purpose of obtaining the demographic information of the respondents by using nominal data. The remaining sections of the survey (Part B – Part G) were designed to meet the objectives of this study. The section which surveyed on legal and policy measures on information lock-up contains 19-variables, based on five-point Likert scale ranging from the lowest to the highest (1=Strongly Disagree, 2=Disagree, 3=Not Sure, 4=Agree, 5=Strongly Agree). The variables were derived from the legal and policy measures to overcome public information lock up which are currently adopted in the United Kingdom (UK), Canada and New Zealand.

Sample

For the purpose of comparison, the UK, Canada and New Zealand have been selected as sample countries. While admittedly there are over 96 countries with the right to information legislation (Trapnell, 2014), these three countries are the best countries for the purpose of comparison with Malaysia since they share similar legal system with Malaysia. Like Malaysia, Canada and New Zealand are former colonies of England, which inherit Common Law system and similar colonial era legislations. However, unlike Malaysia, the UK, Canada and New Zealand have taken appropriate legal and policy measures to overcome legal impediments to citizens’ right to information.

As for the survey, the target population for the survey are representatives of the government agency, independent statutory body, civil society and academia. A stratified, purposive sampling is used to select the respondents among the population of this study. The criteria for selections are legal officers who are currently attached with the Attorney General’s Chambers and Malaysian Anti-Corruption Commission, as well as civil rights activists and academics who are experts in constitutional and human rights laws.

Data Collection

Data collection for this research is mixed-modes approach comprising field work to collect primary data and library based research to collect secondary data. Secondary data was drawn from primary legal sources in the form of legislative texts comprising of statutes and codes (collectively referred as ‘the Laws”) and regulations and non-legislative texts such as policy, procedures and guidelines (collectively referred as “the Policies”). The laws and policies were collected from the official websites of the government of selected countries. Altogether 3 laws and 7 policies were collected for analysis, listed below:

For primary data, a cross-sectional data was collected from the survey population. Data collection was conducted between 2 January 2017 until 1 April 2017. Survey was conducted with 20 respondents from the Attorney General’s Chambers and Malaysian Anti-Corruption Commission. For the purpose of triangulation, 20 respondents who are civil rights activists and academic experts in constitutional law and human rights law were also surveyed. Self-administered survey questionnaires were distributed by the researchers to the target population by hand using stratified, purposive sampling techniques. The language of instruction for the survey is English and each respondent was allocated approximately thirty minutes to answer the survey questionnaires. The completed survey questionnaires were then collected by the researchers themselves.

Data Analysis

For qualitative data, a legal, doctrinal and policy analysis were made on the primary and secondary legal sources. Further, a comparative analysis was made on the laws and policies from the UK, Canada and New Zealand based on three criteria’s: similarities, differences and special/unique features of the legal and policy measures adopted in the selected countries. The scope of comparison is pertaining to the legal and policy measures which overcome public information lock up in the selected countries. A normative analysis approach to determine what the laws and policies ought to be, was applied to answer the second research questions. The normative analysis approach which requires analysis of both the primary and secondary data is important as the aim of this study is to develop a legal and policy framework to overcome public information lock up in Malaysia.

As for quantitative data, the survey data was analysed using descriptive analysis. The nominal data was analysed to find the Mode. The ordinal data was statistically analysed to rank and to find the Median for each variables in the Likert scale and the Means was used to describe the scale.

Findings

What are the legal and policy measures most appropriate to overcome public information lock up?

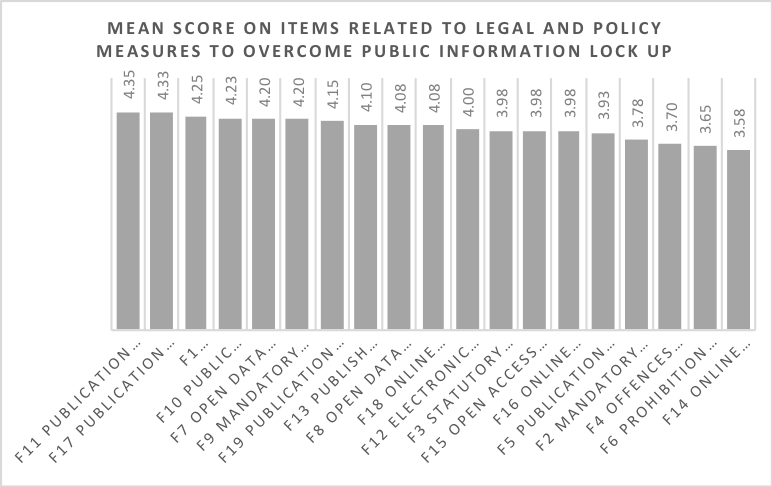

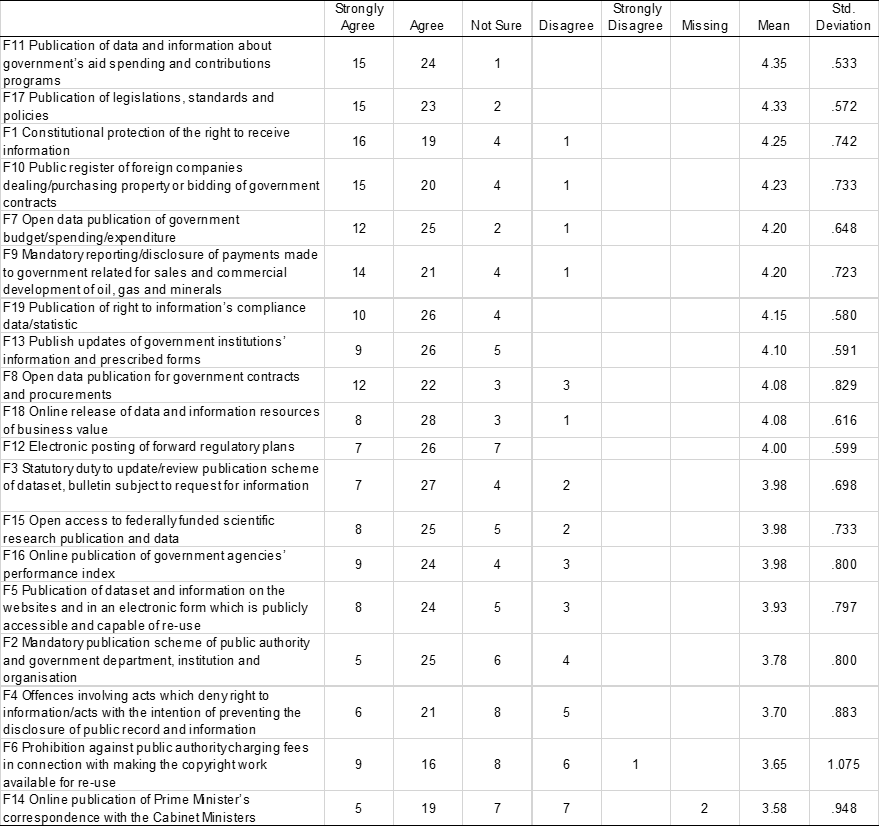

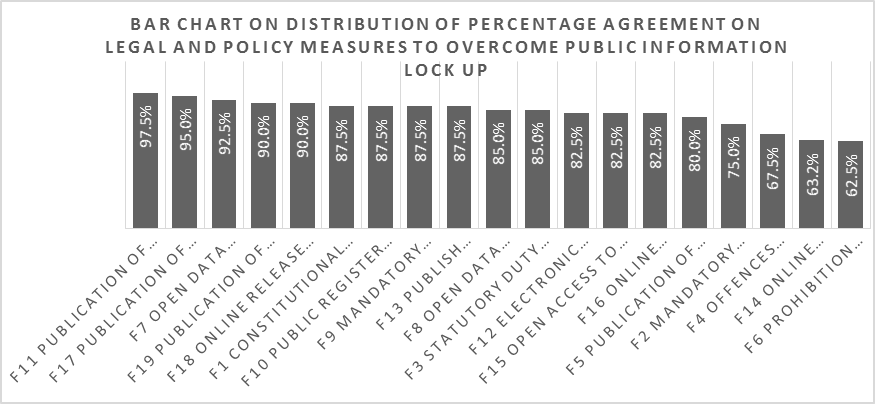

The figures below illustrate the findings of the survey conducted with 40 respondents for the purpose of determining the legal and policy measures most appropriate to overcome information lock up in Malaysia. Nineteen (19) variables asked in the survey serve as the legal and policy measures to overcome public information lock up. Likert scale is used to depict the appropriateness of the legal and policy measures to overcome public information lock up. The Likert scale used are as follows: 1=Strongly Disagree, 2=Disagree, 3=Not Sure, 4= Agree, 5=Strongly Agree. The summary of the analysis result is as presented in Table(s) and Figure(s).

Based on the descriptive analysis, it is found that the highest Mean value is 4.35 (publication of data and information about government’s aid spending and contribution programs), followed by 4.33 (Publication of legislations, standards and policies). The lowest Mean value is 3.58 (online publication of Prime Minister’s correspondence with the Cabinet Ministers). There are 11 variables which recorded a Mean value above 4.00, while 8 others recorded Mean values between 3.58 to 3.98. There are 3 variables with equal Mean value of 3.98; i) open access to federally funded scientific research publication and data; ii) online publication of government agencies’ performance index; and iii) statutory duty to update/review publication scheme of dataset, bulletin subject to request for information. There are also variables: i) Mandatory reporting/disclosure of payments made to government related for sales and commercial development of oil, gas and minerals; and ii) open data publication of government budget/spending/expenditure which recorded equal Mean value (4.20). Another variable which recorded same Mean value are: i) online release of data and information resources of business value; ii) open data publication for government contracts and procurements (4.08). The Mean values for all the variables surveyed range between 3.58 to 4.35. The findings indicate that the respondents of this survey mostly agree as to the appropriateness of the legal and policy measures to overcome public information lock up in Malaysia.

Analysis of Median value based on organization attached, found that a Median value of 3.50 is recorded from the respondents of the government agency for the following variables: i) online publication of government agencies’ performance index; and ii) publication of dataset and information on the websites and in an electronic form which is publicly accessible and capable of re-use. As from the respondents representing independent statutory body, the highest Median value is 4.50 for: i) constitutional protection of the right to receive information; and ii) publication of legislations, standards and policies. The lowest Median value of 2.50 is recorded from the respondents of the independent statutory body for prohibition against public authority charging fees in connection with making the copyright work available for re-use. As for respondents representing civil society, Median values above 4.00 are recorded for: i) constitutional protection of the right to receive information (4.50); ii) open data publication of government budget/spending/expenditure (5.00); iii) open data publication for government contracts and procurements (4.50); iv) mandatory reporting/disclosure of payments made to government related for sales and commercial development of oil, gas and minerals (4.50); v) public register of foreign companies dealing/purchasing property or bidding of government contracts (4.50); and vi) publication of data and information about government’s aid spending and contributions programs (5.00). A high Median value is also recorded from the academia whereby Median value 5.00 is recorded for: i) open data publication for government contracts and procurements; ii) mandatory reporting/disclosure of payments made to government related for sales and commercial development of oil, gas and minerals; iii) public register of foreign companies dealing/purchasing property or bidding of government contracts; iv) publication of data and information about government’s aid spending and contributions programs; and v) publication of legislations, standards and policies. Therefore, it can be concluded that, the academia and civil rights activists are more receptive to the legal and policy measures to overcome public information lock up compared to the respondents of the government agency and independent statutory body.

In terms of Mode value for each variable, publication of data and information about government’s aid spending and contributions programs recorded the highest Mode value of “Agree and Strongly Agree” at 97.5%. The lowest Mode value for “Agree and Strongly Agree” response is prohibition against public authority charging fees in connection with making the copyright work available for re-use (62%). This is followed by response for i) online publication of Prime Minister’s correspondence with the Cabinet Ministers (63.2%); and ii) offences involving acts which deny right to information/acts with the intention of preventing the disclosure of public record and information at 67.5% who “Agree and Strongly Agree”. Other variables recorded Mode values for “Agree and Strongly Agree” response between 80% to 87.5%. From the above findings, this study observes that overall the respondents either “Agree” or “Strongly Agree” as to the appropriateness of the legal and policy measures to overcome public information lock up. Therefore, all 19 variables are appropriate for adoption as part of the legal and policy frameworks to overcome public information lock up in Malaysia.

How should a legal and policy frameworks be developed to overcome public information lock up in Malaysia?

The main purpose of developing a legal and policy framework is to provide constitutional and legal rights to overcome public information lock up in Malaysia. In developing the frameworks, findings of the survey reported above are given prime consideration. The variables which record high Mean, Median and Mode values are adapted into the legal and policy frameworks. Established principles of citizen’s right to public information are also incorporated as part of the frameworks.

Conclusion

This study has achieved its aim to develop a legal and policy frameworks to overcome public information lock up in Malaysia. The legal and policy frameworks developed by this study are of international standard as the legal and policy measures were adapted from the UK, Canada and New Zealand. Since the frameworks comprised both legal and policy measures, they serve as authoritative instruments to overcome public information lock up in Malaysia. The implementation of the legal and policy frameworks requires the Federal Constitution and impeding statutes to be amended, and new legislation and policies to be introduced.

Due to time and budget constraints, the comparative analysis by this study only covers three countries and its survey only involves 40 respondents. In future, the comparative analysis could be expanded to include other jurisdictions from ASEAN and non-Commonwealth countries particularly USA. Further, the survey could be expanded to other government agencies, independent statutory bodies, as well as members of civil society and academic institutions not covered by this study. As this study focuses on information lock up, future research should focus on overcoming information lock out and information lock down which impede citizens’ right to seek and impart public information.

Being a legal study, this research does not conduct feasibility study to carry out the legal and policy measures. However, since data and information in present day mostly exist in digital format, it is anticipated that public information can be released online, hence more costs efficient. This study also does not investigate attitude and readiness among legislatures and the civil servants, being the main stakeholders in passing and implementing the legal and policy frameworks. Hence, further study should be conducted to fill in the gaps left by this study.

References

- Amnesty International. (2015). Malaysia: Court ruling on Sedition Act yet another blow to freedom. Retrieved from http://www.amnesty.org.au/news/comments/38165.

- Bhatt, H. (2011, November 27). Groups welcome FOI enactment, point out weaknesses. The Sun Daily. Retrieved from newsdesk@thesundaily.com.

- Bhatt, H. (2010). Making access to information a right. Retrieved from http://www.malaysianbar.org.my/general_opinions/comments/making_access_to_information_a_right.html.

- Fernandez, J. (2016). Hindraf calls for freedom of Information act. Retrieved from http://www.freemalaysiatoday.com/category/nation/2016/02/08/hindraf-calls-for-freedom-of-information-act/.

- Floridia, A. (2013). Participatory democracy versus deliberative democracy: Elements for a possible theoretical genealogy. Two histories, some intersections. Paper presented at the 7th ECPR General Conference Sciences. Bordeaux.

- Janssen, K. (2012). Open government data and the right to information: Opportunities and obstacles. The Journal of Community Informatics, 8(2).

- Johan, S. (2013). Goodbye to whistle-blowers. The Star. Retrieved from http://www.malaysianbar.org.my/members_opinions_and_comments/goodbye_to_whistleblowers.html.

- Legault, S. (2012). Canada’s access to Information Act: Modernizing the access to Information Act: An opportune. Office of the Information Commissioner of Canada.

- Mishra, A. (2013). Right to information empowerment or abuse. Retrieved from http://lawmantra.co.in/right-to-information-empowerment-or-abuse-2/.

- Muhamad Izwan, I. (2014). Legal hurdles in freedom of information in Malaysia. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2470291.

- Low, Paul. (2015, 18 August). Malaysia not ready for freedom of information act. The Star. Retrieved fromhttp://www.thestar.com.my/news/nation/2015/08/18/paul-low-data-free/.

- Peled, R., & Rabin, Y. (2011). The constitutional right to information. Columbia Human Rights Law Review, 42, 357.

- Pradeep, K.P. (2012). The right to information – New law and challenges. Retrieved from http://rti.kerala.gov.in/articles/art001eng.pdf.

- The Constitution Unit UCL. (2011). Freedom of information and data protection. Retrieved from https://www.ucl.ac.uk/constitution-unit/research/foi/countries/malaysia.

- The Malaysian Insider. (2014). Replace official secrets law with freedom of information act, urges young lawyers group. Retrieved from http://www.themalaysianinsider.com/malaysia/article/replace-official-secrets-law-with-freedom-of-information-act-urges-young-lawyers.

- Trapnell, S. E. (2014). Right to information: Case studies on implementation. World Bank Group.

- Yong, A. (2016). Communications and Multimedia Act 1998 needs to be amended. Retrieved from https://www.malaysiakini.com/letters/331781.

- Zausmer, R. (2011). Towards open and transparent government: International experiences and best practice. Global Partners and Associates.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

31 December 2018

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-051-8

Publisher

Future Academy

Volume

52

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-949

Subjects

Company, commercial law, competition law, Islamic law

Cite this article as:

Hashim, H. N. M., Zain, F. M., Suhaimi, N. S., Yahya, N. A., & Mahmood, A. (2018). Legal And Policy Frameworks To Overcome Public Information Lock Up In Malaysia. In A. Abdul Rahim, A. A. Rahman, H. Abdul Wahab, N. Yaacob, A. Munirah Mohamad, & A. Husna Mohd. Arshad (Eds.), Public Law Remedies In Government Procurement: Perspective From Malaysia, vol 52. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 523-534). Future Academy. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2018.12.03.51