Abstract

The Alternative Dispute Resolution or ADR offers an effective and harmonious settlement of disputes involving, inter alia, family, school, community, sports, workplace, business, medical and even political. This study examined the ADR knowledge among the Malaysian public, i.e. the professional public and the non-professional public. The respondents were assessed on ADR knowledge through respondents’ self-rating on how much they knew about ADR on a 5 Likert items (High, Quite High, Moderate, Low and None). The purposive random sample comprised of 250 respondents residing in Klang Valley. The data were collected using a self-developed structured questionnaire which was administered online, i.e. WhatsApp and e-mail to arrive at the findings. Descriptive statistics and inferential statistical analysis were applied, while independent-samples t-tests were used to analyse the data. The results showed that more than 80% of the non-professional public have low level or no knowledge about ADR. The results of the t-tests point to a statistically significant difference between the professional public and the non-professional public. The findings suggest the importance to conduct conscious public campaign on awareness and understanding of ADR and its processes so as to ensure effective application of ADR as the preferred alternative dispute resolution to access justice.

Keywords: ADRknowledgeprofessional publicnon-professional public

Introduction

The Alternative Dispute Resolution or ADR is a process where a neutral intermediary, a mediator or arbitrator, aids disputing parties to come to a settlement agreement. The occurrence of conflicts afflicting humankind has been an unending affair since time immemorial. The Chinese, Arabs, Indians and Malays communities have been using ADR effectively as a customary or traditional method to resolve disputes amicably for several generations. ADR resolves disputes in an informal and consensual manner unlike the court litigation. The most common forms of ADR include, inter alia, mediation, arbitration and litigation. The increasing popularity of ADR, particularly mediation and arbitration, has led to many law firms setting up the dispute resolution department. Also, the government has been actively promoting ADR to civic organizations and practitioners from the legal and business fraternities, families and communities to use ADR in resolving their disputes. However, the general public awareness and understanding of ADR are still wanting in Malaysia

Many researchers have documented the application and development of ADR across the different legal jurisdictions and time periods. Wan Muhammad (2008) and Mo (1999) commented that historical events exposed elements of dispute resolution among the ethnic cultures of Malays, Chinese and Indians. While Spencer & Brogan (2006), Boulle & Nesic (2001) and Yuan (1997) conducted studies on the development of traditional and modern mediation respectively. These authors reported that the indigenous populations used negotiation and consultation as a method of resolving disputes but employed varied approaches according to their cultural norms. These communities appreciated the benefits of ADR and embraced it as a customary way to settle whatever conflicts that they faced. Thus, their level of awareness and understanding of ADR, especially mediation and arbitration, were high. Unfortunately, modernization and urbanization have eroded the use of ADR and disputes are commonly settled by court litigation which is costly, lengthy and damaging to cordial human relationships. In contrast, the modern mediation which started in the United States of America is a very recent phenomenon. It has become popular throughout the world as an alternative to litigation involving the adversarial court trials. The preference for court litigation by contending parties has caused a severe perennial backlog of cases which deny access to justice for many litigants in many countries. For example, the courts in Malaysia have seen a continued rise in the backlog of cases. The judiciary reported that for civil cases alone, the High Court registered some 93,523, the Sessions Court some 94,554 and the Magistrates Court some 156,053. By December 2008, the backlog of cases at the High Court and the Subordinate Court had increased to 344,130 (Report of Bar Council, 2008). Despite the courts’ efforts to tackle the problem, there are still old cases which cannot be cleared as fast as new ones are being registered. The backlog of cases is still pending in the Malaysian court system and if society becomes more litigious the problem will persist forever. This brings about the importance of introducing ADR, especially MedArb (mediation cum arbitration) to resolve disputes either at family, community, school, sports, workplace, business, medical and even political levels to settle present and future disputes out of court harmoniously.

Pursuant to resolve the serious backlog of cases, the initial effort to introduce mediation was undertaken by Chief Justice Tun Zaki Azmi (2010) who issued the Practice Direction No. 5 of 2010 (PD) on 16 August 2010 to formalize the requirement of mediation in the courts. The PD allows the civil courts a legal framework to conduct mediation as part of the court proceeding under 34 Rule 2 (Rules of High Court, 2012). The application of mediation was made by the Court-Annexed Mediation at the pre-trial case management phase. The effort was so successful that all judges were encouraged to get litigants to go to mediation before going further for court adjudication. Seeing the success of mediation, the legislature introduced the Mediation Act 2012 (Act 749) to officially promote mediation. The Act introduced by Parliament came into force on Aug 1, 2012 is aimed at promoting and encouraging mediation as a method of alternative dispute resolution to settle disputes in a fair, speedy and cost- effective manner. In order to further boost the application of mediation and arbitration as an alternative to the court adjudication, the Chief Justice Tun Ariffin Zakaria (2016) issued another Practice Direction No. 4 of 2016 which mandated mediation to be directed to all Courts, the Kuala Lumpur Regional Centre for Arbitration (KLRCA), the Malaysian Mediation Centre (MMC) and other mediation bodies on 30 June 2016. However, to date the initiative has received a lukewarm reception from the general public as a huge majority are still lacking in the knowledge of ADR and its processes despite the enormous benefits ADR bring.

Certain types of ADR offer effective dispute resolution methods which range from negotiation, mediation, arbitration, neutral evaluation, ombudsman, mini-trial and some other mixed forms so that they could be used to support and strengthen the administration of justice. Such mechanisms are considered as effective and affordable complements to litigation because they ensure fast and affordable settlement of disputes. Besides, effective dispute resolution has relevance for a broad range of sectors and civil society activities (Abdul Hamid & Nik Mohammad, 2016). Historically, the societies around the world have strong traditions of conciliatory and community-based problem-solving. In mediation, a neutral intermediary tries to help disputants come to a compromise settlement. A professional mediator assists the disputants in exploring the interests underlying their positions, working together with them and/ or separately to resolve the conflict and arrive at a solution which is sustainable, voluntary, and non-binding. While in arbitration, a private arbitrator or a panel of arbitrators serves as an adjudicator responsible for deciding the dispute. The arbitrator conducts the adjudication session by listening to both parties presenting their arguments and supporting relevant evidence before rendering a binding decision. A mixed form of ADR which is getting more recognition is MedArb, a mediation-arbitration hybrid. In MedArb, the disputants employ a neutral mediator cum arbitrator. If the mediator is unable to settle the dispute via mediation, the mediator switches to arbitration and renders a binding decision.

In this context, Charlton & Dewdney (2004) stated that the mediation process is applicable to all forms of dispute, whether it be commercial, workplace, family, neighbourhood and environment. It clearly outlines the required skills, techniques and strategies, especially communication skills. A variation to the mediation process requires the roles of advisers, support personnel and interpreters having listening skill, both passive and active, which constitute an essential tool in mediation. They are applied for purposes other than understanding the situation in order to give advice or for the mediator to suggest a solution. On the same premise, Seumas (2012) commented that a mediator is a person who is neutral, impartial and a facilitator rather than a channel of communication between parties. A mediator tends to concentrate and focus on resolving the dispute rather than getting to know the parties’ real needs. The writer opined that Neuro-Linguistic Programming (NLP) would help parties communicate and thus settle their disputes. NLP uses techniques such as framing, mirroring, associating or anchoring and listening skills; while Ali Mohamad & Lau (2012) highlighted the much needed mediation skills, knowledge and competencies that mediators must possess and also the meeting for regular professional debriefing. The purpose of debriefing is to address matters relating to skills development, conceptual and professional issues, ethical dilemmas, ensuring the emotional health of mediators who participate in the continuing professional development training. This would enable mediators to be competent and have the capacity to apply knowledge, skills and an ethical understanding and commitment in the mediation process.

In commenting about the future prospect of mediation in Australia, McIntyre (2005) reported that the next decade is likely to see growth in the trend in non- curial dispute resolution processes such as mediation, neutral evaluation and arbitration by agreement. This change would be largely driven by the increasing costs of litigation and involve different skills for solicitors. His view was supported by the comment made David Spencer at the Australasian Law Teachers Association Conference in July 2005 where it was reported that the reduction in filings and trials in the NSW District Court may ultimately lead to a significant change in the future practice of laws. He concluded that unless the trial had a facelift, it was at risk of vanishing and being replaced by other forms of adjudication and non-curial dispute resolution. In support of the motion, Haydn-Williams (2017) reported that the settlement rates using mediation in the UK are in the order of 60-70%. But one study of court users in England and Wales revealed that only 23% adopted it, some 43% were aware of it and some 34% had not even heard of it. This means that some 77% of the population had no knowledge of ADR and its processes. Given the quicker, cheaper and usually better outcomes of successfully mediated cases, a huge opportunity has, in the recent past, being missed by those were responsible for the funding and administration of civil justice. Lord Justice Briggs’ proposals for change seem to recognize this fact, with mediation an integral part of them. On another front, the application of mediation by sports bodies is of a recent development as compared to sports arbitration, which has dominated the sports dispute resolution at the Court of Arbitration for Sport (CAS). Nonetheless, the suitability of mediation in resolving sports disputes has been recognized by sports associations and federations. CAS has introduced a mediation clause within their dispute resolution rules. The success rate varies. It was reported that the CAS introduced mediation in 1999. It has handled some 50 mediation cases covering disputes related to football, cycling, boxing, motocross, judo, and basketball (Svatos, Alexander, & Walsh, 2017). Given the above scenarios, there are many precedents from other jurisdictions that the government can learn to adopt and adapt to boost the ADR initiatives for an effective, successful and harmonious dispute resolution initiative.

Problem Statement

The perennial court trial delays and the antagonism of the adversarial system have caused tensions to rise among the litigants, creating animosities among parties and affected their well-being. The court system is too legalistic, bureaucratic and costly. The general public is lacking in the knowledge of ADR and its processes. Thus, they rely solely on lawyers and court litigation to settle their disputes notwithstanding paying a heavy cost. The government is determined to promote mediation and arbitration as an alternative dispute resolution to resolve disputes, either in family, school, community, sports, workplace, business, medical and even political levels so as to refrain parties from going to the court. Despite the passage of the Mediation Act 2012 (Act 749) and the Practice Direction No. 4 of 2016, the general public has yet to respond positively to adopt ADR to settle their conflicts. The continued increase of backlog of cases in the courts provides irrefutable evidence of this state of affairs.

Research Questions

The study seeks to answer the questions on the levels of the general public knowledge of ADR in Malaysia.

What is the level of ADR knowledge among the general public?

Is there a statistically significant difference in the ADR knowledge levels between the professional public and the non-professional public?

Purpose of the Study

The purpose of this study is to examine the levels of ADR knowledge among the Malaysian public. The study also set to determine if statistically significant differences existed between the professional public and the non-professional public. Thereafter, specific programs on awareness and understanding of ADR and its processes can be introduced. By taking such initiative would ensure its success, recognition and acceptance by the general public to path the way for an effective and sustainable application of ADR in resolving disputes.

Research Methods

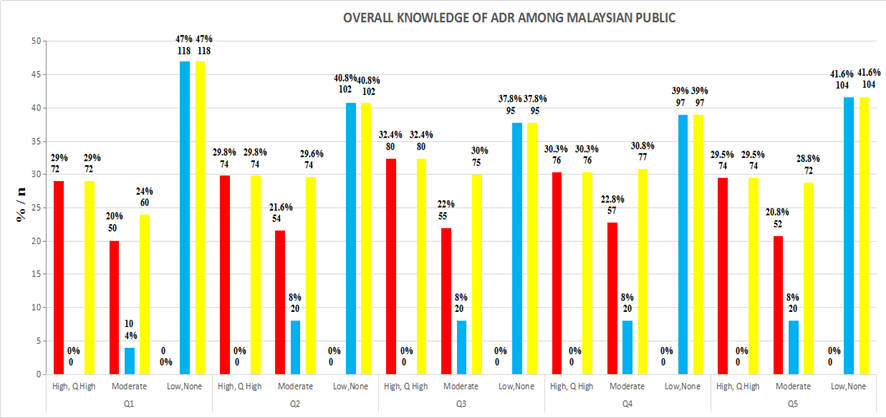

The study was a cross-sectional designed to identify the levels of respondents’ knowledge of ADR and to compare these levels between the professional and non-professional public. The population sample consisted of 250 respondents of professionals and non-professionals public in Klang Valley. The questionnaires were administered online using the Google Form. The researchers used a number of follow-up measures, i.e. email reminders and phone calls to ensure a high response rate. The response rate was 100%. Data were collected using a self-developed questionnaire that contained 5 ADR knowledge items which asked the respondents to rate, on a 5- point Likert scale (High, Quite High, Moderate, Maybe and None) the degree of their ADR knowledge. After being generated, the items were subjected to validation by a psychometric expert and later pilot tested on a representative sample of the target respondents. The reliability of the data generated from the items was found to be high, i.e. a=0.92 showing a good indicator of reliability of the study. To address research question responses to the 5 Likert items on knowledge of ADR was collapsed and the mean percentage for each response category, i.e. High, Quite High, Moderate, Maybe and None, was computed. To address the research question 1 and 2, the responses to the 5 items were graded and given a score, i.e. 3 for High/ Quite High, 2 for Moderate, 1 for Maybe and 0 for None. The scores were then summated, yielding a group score each for respondents. Two independent-samples t-tests we performed on the group scores to see if statistically significant differences existed between the two groups with respect to the levels of ADR knowledge. The level of statistical significance adopted for the analysis was p ≤ 0.05, which formed the basis of whether a significant difference existed between the two groups or not. The first research question asked “What is the level of ADR knowledge among the general public? While the second research question asked “Is there a statistically significant difference in the ADR knowledge levels between the professional, public and the non-professional public?” A percentage analysis of the five Likert items of the first research question is presented in Chart 1 and Table

The independent sample t-test analysis was conducted to examine the differences between the professional public and non-professional public in terms of their ADR knowledge. The study involved 250 respondents. The result of the study showed that there is a statically significant difference between the professional public and non-professional public at t (237.624) = 23.779, p = 0.001. The professional public showed their higher knowledge (M = 13.84, SD = 2.03) o ADR as compared to the non-professional public (M = 4.75, SD = 3.97).

The independent sample t-test analysis was conducted to examine the differences between Professional Public and General Public in terms of their ADR knowledge. The study involved 250 respondents. The result of the study showed that there is a statically significant difference between Professional Public and General Public at t (237.624) = 23.779, p = 0.001. Professional Public showed their higher knowledge (M = 13.84, SD = 2.03) compare to General Public (M = 4.75, SD = 3.97).

Findings

Several key findings were derived from the study. First, the non-professional public has a low level of ADR knowledge as compared to the professional public. The non- professional public who are composed of educators, students, working people and small business owners are rarely exposed to the concept of ADR due to the nature of their jobs. It was observed that in the course of their daily work and activities they are not confronted with complex disputes, perhaps only to those that are domestic and occasionally interpersonal in nature. Thus, there is no need to resort to engaging a lawyer to settle the dispute which can be easily settled via negotiation, given the fact that the terms such as mediation and arbitration are alien to them. However, a large number of the non-professional public (> 80%) was reported to have low level or none of ADR knowledge. The pattern implies a likelihood of finding more Malaysian public who would not know about ADR and its processes. On the other hand, the professional public appears to have better ADR knowledge. This finding was expected because this group of people comprised of legal practitioners, doctors, engineers, accountant and business executive. The situation is different from the non-professional public because as for the professional public, their job involve the observation of complex agreements, job specifications, business transactions and costly overheads. Whenever a dispute arises, it is very complex, requiring the interpretation of the legal documents, processes and expensive cost related matters. The employment of the company’s lawyers and litigation would readily be available because of the onset of the business undertakings, the lawyers and other professionals have been involved in the formulation of the contracts and related matters. The options to resort to mediation or arbitration are already enshrined in the provision of the contractual agreement and alert these professionals on the notice to resort to ADR. Moreover, a big majority of the professionals have attended tertiary education and the courses offered by the educational institutions would have included ADR as part of the course requirements. Thus, explains the high level of knowledge of the professional public in the level of the ADR knowledge. The overall findings suggest the importance to raise the level of awareness and understanding of ADR knowledge among the non-professional public by promoting public campaigns and short-training courses for the non-professional public to enhance their awareness and understanding of ADR, its processes and benefits so as to ensure the successful acceptance and application of ADR as an effective dispute resolution.

Conclusion

The government and the judiciary have promoted the ADR initiative to dispose the backlog of cases in our courts and improve access to justice. The introduction of ADR, especially mediation and arbitration, to the courts and local institutions can be successful in removing the backlog of cases and improve access to justice for all Malaysians if the general public are aware and understand ADR and its processes as well. Therefore, there must be a concerted effort by the government and ADR institutions to organize a nationwide campaign on ADR and its processes to the general public per se to ensure effective and successful application of ADR initiative.

Acknowledgments

This research is sponsored by the Multimedia University Malaysia.

References

- Abdul Hamid, M.I. & Nik Mohammad, N.A (2016). Cross culture jurisprudential influence on mediation in Malaysia. Malayan Law Journal, 4, xli.

- Ali Mohamed, A.A. & Lau, W.K.H. (2012). Accreditation of mediators in Malaysia. In Ali Mohamed, A.A. and Ishan Jan, M.N. (Ed). Mediation in Malaysia: The law and practice. Malaysia: LexisNexis.

- Boulle, L. & Nesic, M. (2001). Mediation, principles, process, practice. United Kingdom: Butterworths.

- Charlton, R. & Dewdney, M. (2004). The mediator’s handbook, skills and strategies for practitioners (2nd ed.). Sydney: Lawbook Co.

- Haydn-Williams, J. (2017). Retrieved from <http://www.mondaq.com/redirection.asp?article_id=596916&author_id=639420&type=articleauthor>

- McIntyre, J. (2005). “President’s column”. Law Society Journal, 43(7), 4.

- Mo, J.S. (1999). Non-judicial means of dispute settlement in Chinese law. In Guiguo, W. & Mo, J. (Ed). Chinese law. The Hague: Kluwer Law International.

- Report of Bar Council. (2008).

- Rules of High Court. (2012).

- Spencer, D. & Brogan, M. (2006). Mediation law and practice. UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Seumas, T. (2012). Mediation skills and techniques a practical handbook for dispute resolution and effective communication. Malaysia: Sweet & Maxwell Asia.

- Svatos, M., Alexander, N. and Walsh, S. (2017). EU Mediation Law Handbook. Kluwer Law International.

- Tun Ariffin Zakaria. (2016). Practice Direction No.4 of 2016 / Practice Direction on Mediation.

- Tun Zaki Azmi. (2010). Overcoming case backlogs, the Malaysian experience. Asia Pacific Court Conference, October 4-8, Singapore.

- Wan Muhammad, R. (2008). The theory and practice of sulh (mediation) in the Malaysian Shariah Court. IIUM Law Journal, 16.

- Yuan, L.L. (1997). The theory and practice of mediation. Singapore: FT Law & Tax Asia.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

31 December 2018

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-051-8

Publisher

Future Academy

Volume

52

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-949

Subjects

Company, commercial law, competition law, Islamic law

Cite this article as:

Hamid, M. I. A., Mohammad, N. A. N., Dhillon, G., & Jacobs, C. G. M. C. (2018). Knowledge Of Adr: A Critical Success Factor For Effective Dispute Resolution Initiative. In A. Abdul Rahim, A. A. Rahman, H. Abdul Wahab, N. Yaacob, A. Munirah Mohamad, & A. Husna Mohd. Arshad (Eds.), Public Law Remedies In Government Procurement: Perspective From Malaysia, vol 52. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 26-34). Future Academy. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2018.12.03.3