Abstract

The article explores the issues of the development of intercultural competence of future teachers and their readiness to work in a multicultural environment. It provides the results of cross-cultural research in Russia and such European countries as Belarus, Poland, Germany, France and Great Britain. The study was conducted in 2013-2017 with the support of research centres at universities of Belarus, Poland, the UK, and etc. This cross-cultural research aims at revealing the outlook, characteristic of each particular culture. The purpose of the research is to identify the features of national identity of Muslim migrants and of the indigenous population aged 17 to 30. The analysis of the results led to the following conclusion that: 1) manifestations of extremism among Muslim migrants are not connected with a correct (or incorrect) policy of the state or cross-cultural education in the host country, but it is connected with the situation (political, economic, social, etc.) in their ethnic homeland; 2) conceptual, strategic and technological structures of cross-cultural education should take into account this interference (negative impact of the ethnic situation in one country on the subconscious of the subjects of cross-cultural education in another country); these structures should not aim at assimilation of migrants but at overcoming this interference in their ethnic consciousness; 3) methods of transposition (positive transfer of cultural components of an ethnic homeland to the culture of the country of migrants’ residence), aimed at creating a positive intercultural dialogue with representatives of different ethnic groups should be used in cross-cultural education.

Keywords: Multicultural educationintercultural competencefuture teacherscross-cultural researchnational identityethnic tensions

Introduction

Issues related to intercultural education have become the focus of international research. The studies conducted by Makhmutov (2006), Podgoretski and Gabdulhakov (2014), Zhigalova and Gabdulhakov (2013) et al. prove that intercultural education is an important means of easing interethnic conflicts at schools and in social life. This stance, to a great extent, can be viewed as a consequence of mass immigration from the East and Northern Africa. In Russia, Muslim migrants have become the cause of ethnic and religious tensions and the basis for extremist nationalist movements.

In cross-cultural psychology, mutual attitudes of representatives of different ethnic groups are investigated (Allport, 1961; DeRider and Tripathi, 1992; Giles, Bourhis, & Taylor, 1977; Tajfel and Turner, 1986); psychological measurements of culture (Gudykunst, 1995; Triandis, 2002); the influence of anxiety and uncertainty on effective interpersonal and intergroup interaction (Gudykunst, 1995; Stephan and Stephan, 2001; Islam and Hewstone, 1993); in the context of intercultural adaptation, "cultural shock" (Berry, Poortinga, Segall, & Dasen, 1992); multiculturalism (Berry, 1997).

Currently, researchers from different countries are involved in the development of the conceptual, strategic and technological foundations of intercultural education. However, quite a number of these strategies narrow down to the technology of acculturation and assimilation of ethnic minorities. For example, Bublik (2013) explored in the gender and educational aspects the psychosemantic space of the ethnic identity of the youth of eight ethnic groups (Russians, Ukrainians, Belarusians, Armenians, Tatars, Azerbaijanians, Dagestanis and Chechens) in the same region (Bublik, 2013). In this regard, we may recall the US history which shows that the population of the country has historically formed due to the influx of migrants. Experts assumed that ethnic minorities would assimilate and disappear in the course of urbanization and the development of post-industrial society somewhere in the middle of the twentieth century. In reality, everything went the other way – a sense of ethnic identity in some groups (e.g., Arabs, Chinese and Japanese) has strengthened, in others (e.g., Germans, French, Poles), it has disappeared.

It is already evident that Muslim Arab migrants want to preserve their native language and traditional values. Moreover, extremism manifests itself both in new migrants and in the children and grandchildren of the last century migrants, those who were born and educated in that country, who acquired the language and culture of the indigenous population. Research in Russia, Belarus, Poland, Germany, France, England countries suggests Muslim Arab migrants often want to preserve their native language and traditional values. In conversations, they say that they came to Europe to earn money, and not to learn other people's values.

The subject of cross-cultural studies is the features of the human psyche, which are determined by socio-cultural factors specific to each of the compared ethno-cultural communities. Psychologists are primarily interested in "subjective culture", as culture itself exists as a subjective culture meaning that it exists in the form of shared worldviews, values and internalized patterns of interactions inside individuals. Outside individuals, culture consists of a shared environment, including religious beliefs, educational institutions and aesthetic achievements (e.g. in art, theatre, fictional and documentary works).

However, comparative cross-cultural studies of ethnic tensions in Russia and some European countries are practically non-existent. Such studies are especially needed in the context of European integration of higher education, teacher training included. This cross-cultural research aims at revealing the outlook, characteristic of each particular culture. It is developed in each young child in the process of their interaction with older relatives and objects of their environment. We need to understand how to change children’s intercultural education to prevent their transformation into future terrorists or extremists. Understanding attitudes is important in order to develop interventions that encourage tolerant and multicultural attitudes.

Problem Statement

The Volga region is the central part of Russia inhabited by several large nations such as the Tartars, the Bashkirs, the Chuvashs, the Mari, the Mordovians, the Udmurts. All these nations have their own national identity and official bilingualism in Russia. The problem of national (racial, religious) aggression is usually discussed only when this kind of aggression is faced. The examples are assassinations in the streets and schools in the USA, slaughters in Norway and Great Britain, terrorist attacks in Volgograd, mufti homicide and arson of religious buildings in Tatarstan, confrontations with militants in the North Caucasus in Russia, slaughter of civilians in Odessa, Slavyansk, Kramatorsk in Ukraine and so on. Without doubt, there are other reasons, besides national, behind each of these incidents. That is why state security services, scholars, journalists, lawyers examine a range of political, economic, national, cultural and other reasons. At the same time almost no one studies psychological and pedagogical reasons. In order to examine psychological and pedagogical reasons of national aggression (both latent and overt) one needs to apply a professional approach. We can trace the difference between school teachers' and preschool teachers' opinions about the age when a child should start learning about and developing tolerance and tolerant attitudes. Only 3% of school teachers think that we should start to develop tolerance in little children and 93,8% of preschool teachers are sure this work should begin already in kindergarten. Parents’ responses coincided with those given by school teachers. They did not think about developing tolerance in preschool age though their children attended kindergartens.

Research Questions

The issues of the development of intercultural competence in future teachers and their readiness to work in a multicultural environment are very topical in different countries. Teachers play an important role in fostering and developing values of mutual understanding, readiness to interact with others and tolerance in their pupils. As is known, tolerance (or intolerance) is one of the key issues of interethnic relationships during the period of interethnic tensions, the growth of nationalism and extremism.

The technology of multicultural training should aim at neutralizing aggressive motives that students might have and at developing their intercultural competencies. Relevant teaching should include imparting general theoretical knowledge, use of diagnostic, formative, creative aspects of education, as well as organization of socio-cultural and cultural after-class activities. Students should also participate in different theoretical, experimental psychological and pedagogical work.

Purpose of the Study

The research explores the problem of increasing the effectiveness of multicultural training of future teachers in the context of ethnic tensions by developing multicultural competence, which is considered to be one of the key components of professional teacher education.

The purpose of the research is to single out the features of national identity and find the discrepancy in the degree of tolerance and intolerance between Muslim migrants and the indigenous population aged 17 to 30 in Russia and European countries. Findings of this study can inform about the peculiarities of teaching the language and culture of the host country, about the peculiarities of the national consciousness of migrant Muslims. The results of the study can be used to organize the adaptation of migrants in the host country.

Research Methods

We used the following methods: theoretical (analysis and synthesis of the philosophical, psychological and pedagogical literature on the problems of ethnic identity), empirical (methods of measuring and comparing), and methods of processing research results (qualitative analysis and ANOVA).

We examined ethnic identity and its transformation in the context of interethnic tensions when the level of ethnic intolerance increases. The following criteria were used to assess the degree of ethnic tolerance in the respondents based on the analysis of axiological attitudes: the level of "negativity" in relation to their own and other ethnic groups; the threshold of emotional responses to other ethnic environments; the severity of aggressive or hostile reactions in relation to other groups.

To determine national identity in the context of ethnic tensions the following methods were used: express questionnaires "The Tolerance Index", "The Types of Ethnic Identity" (Soldatova, 2003); the test of general communicative tolerance (Boyko, 1996).

The total sample size was 1800 male and female participants with 300 subjects in each group in six countries; the respondents’ age range was 18-30 years. The analysis of data was conducted by teachers of universities of Belarus, Ukraine, Poland, Germany, France, England. These teachers worked with migrants in their educational centres.

Findings

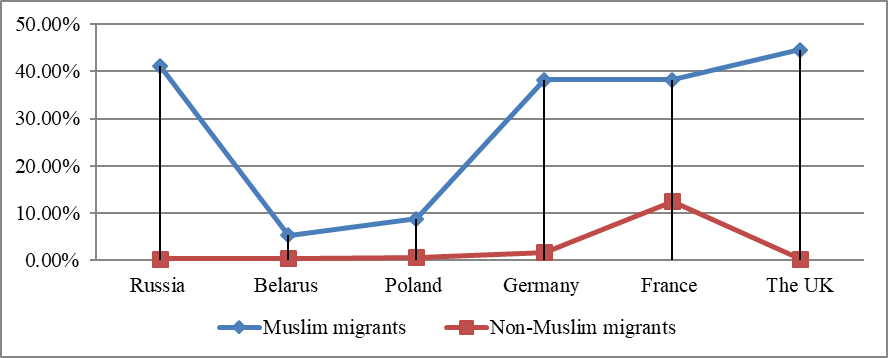

The purpose of the initial stage of the research was to find out which group of migrants, Muslim or non-Muslim, can cause ethnic tensions. Muslim migrants are mostly from the North African countries and the southern CIS countries (Tajikistan, Uzbekistan, etc). Non-Muslim migrants are Ukrainians, Russians, Poles, Bulgarians, living and working in Western European countries.

We studied seven axiological attitudes of the respondents: awareness of the superiority of people of another nationality; a sense of superiority of own nation over people from other nations; non-concealment of own nationality in communication with other people; a feeling of shame for the people of own nationality; a feeling of strain when speaking another language; a feeling of inferiority because of own ethnicity; idea that people of other ethnic groups should be restricted in their right of residence in a host country.

In 2013-2016, we analysed 1800 questionnaires (300 questionnaires from each group in six countries, respondents aged from18 to 30, males and females). The analysis shows (Table

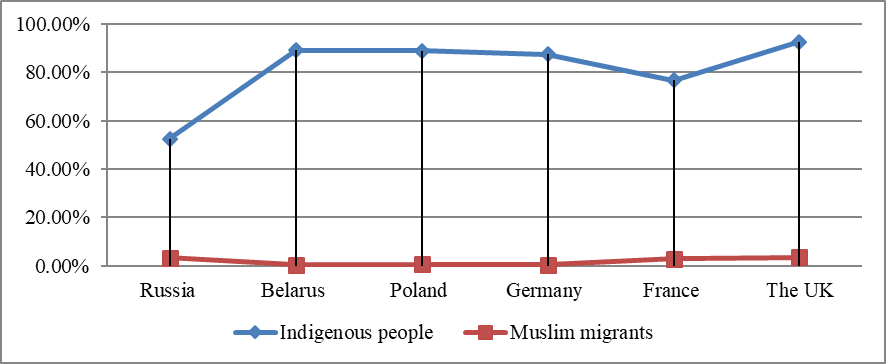

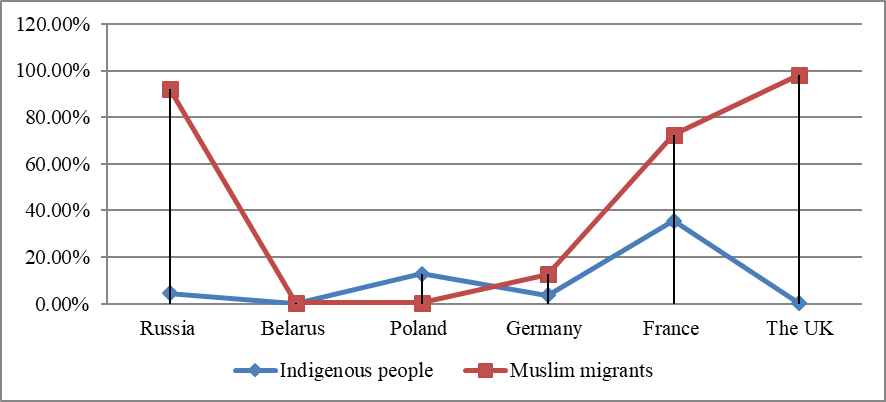

In the next stage of the study, we analyzed only the attitudes of Muslim migrants (M) and indigenous people (IP). We processed 300 questionnaires of migrants and natives from each group in six countries. The analysis was carried out in 2013-2015.

Muslim migrants (M) in different countries look belittled meaning that they are aware of the superiority of people from other nationalities in Russia (92,3%), the UK (98,2%), France (72,5%), Germany (12,7%), Poland (0,5%), Belarus (0,5%).

At the same time, indigenous people (IP) in these countries do not see any overwhelming superiority of other nations. The only exception is France (35,7%) and Poland (12,8%), where indigenous people feel superiority of British people. Indigenous people (IP) feel their superiority over other nations in Russia (93,5%), the UK (99,3%), France (58,6%), Germany (27,7%), Poland (32,7%); the lowest percentage is shown in Belarus (0,4%). These data allow taking a fresh look at the development of nationalist sentiments in these countries. Table

Figures

At the end of the study, respondents completed a questionnaire that contained the following six questions:

Do you consider yourself to have departed from your own ethnic group and have joined any other religious, cultural or ideological group? ;

Can you characterize yourself as a person indifferent to national identity? ;

Is your attitude to your own people and to other nations equally positive? ;

Do you think that your people can solve ethnic problems independently, at "the expense of others," even to the detriment of other peoples? ;

Do you agree that your nation is superior to other nations, and it needs a national cleaning? ;

Do you think that violence and genocide against other peoples can be allowed for the sake of your people’s national interests?

Each question corresponds to a certain type of ethnic identity. The distribution is shown in Table

The results indicate that hypoidentity is most common for Russia and Belarus (12% and 17% respectively), as well as positive ethnic identity (72% and 54% respectively). Positive ethnic identity also prevails in France (31%).

Ethnofanatism and prevails in Poland (30%) and Germany (34%), and ethnoisolationism characterizes the UK (31%). One cause for concern is that those who answered questions 5 and 6 affirmatively do not consider European women to be women. According to Muslim migrants, these "women" should be contemned and ostracized as they appear in public with their faces open, make an eye contact with men and behave like men. The respondents expressed this opinion out of their own will (appending clarifying comments) without any additional questions being asked. The respondents consider a European woman as one of the main annoying aspects of a foreign culture, one of its unacceptable norms.

These results further support the idea that today Russia and some Western European countries are characterized by:

Ethnonihilism as a form of hypoidentity, which is a loss of ethno-cultural orientation and withdrawal from one’s own ethnic group. This type of people search for sustainable socio-psychological orientation based on any but ethnic criteria, possibly religious or ideological, etc.

Ethnic indifference as a form of indeterminate ethnic identity, expressing indifference to human ethnicity. It is especially characteristic of people, originating from mixed marriages.

Positive ethnic identity as a normative form (norm) of positive attitudes towards own nation and other nations.

Ethnoegotism as a form of seemingly innocent verbal perception of intercultural dialogue through the prism of "my people". However, it might suggest tensions, even antagonism, coupled with the recognition of one’s right to solve interethnic problems independently at the expense, even to the detriment of other ethnic groups.

Ethnoisolationism as a specific form of nationalism, the superiority of one’s own ethnic group, the recognition of the need to ‘cleanse’ national culture, the negative attitude towards interethnic marriages, xenophobia, etc.

Ethnofanatism as a form of extreme nationalism. It is associated with people willing to take any action in the name of ethnic (nationalist) interests, recognizing the priority of one’s own national rights over human rights, justifying any casualties in the fight for the prosperity of one’s own nation.

The last characteristic belongs to the group of extreme forms of ethnic identity amplification that may lead to discrimination in the sphere of interethnic relations. In this case, human hyperidentity manifests itself as irritation, aggression, acts of violence against members of other ethnic groups, genocide, etc..

Conclusion

The results of the cross-cultural research into ethnic tensions revealed statistically significant differences in the examined variables reported by the respondents from Russia, Belarus, France, Germany, Great Britain and Poland. At the same time, for a number of variables no differences were found, which indicates the presence of common values and common attitudes of consciousness among people belonging to these six different cultures. As for some certain variables, higher rates were reported by the respondents from Russia and Belarus as opposed to the responses of participants from Western Europe.

We suppose that predominance of positive ethnic identity as a normative form of positive attitudes towards own nation and towards other nations in Russia (72%) and Belarus (54%) is due to the fact that Muslim migrants from the southern CIS countries such as Uzbekistan, Tajikistan and others do not have refugee status and there is no war in their ethnic homeland.

In Western European countries the situation is different as in these countries Muslim migrants (mostly from North Africa) have the status of refugees who lost their homes, loved ones, and their country is in war. In addition, not all of them can be called true Muslims; they are subject to a variety of Islamist currents.

The analysis of the results led to the following conclusions: 1) manifestations of extremism among Muslim migrants are not connected with a correct (or incorrect) policy of the state or cross-cultural education in the host country, but it is connected with the situation (political, economic, social, etc.) in their ethnic homeland; 2) conceptual, strategic and technological structures of cross-cultural education should take into account this interference (the negative impact of the ethnic situation in one country on the subconscious of the subjects of cross-cultural education in another country), these structures should not aim at the assimilation of migrants but at overcoming this interference in their ethnic consciousness; 3) the practice of cross-cultural education should use the methods of transposition (positive transfer of cultural components of an ethnic homeland to the culture of the host country) aimed at creating a positive intercultural dialogue with representatives of different ethnic groups.

Acknowledgments

The work is performed according to the Russian Government Program of Competitive Growth of Kazan Federal University.

We are grateful for the support in conducting these studies to the research centers of the University of Brest (Belarus), the University of Opole (Poland), Oxford and Lancaster Universities (the UK).

References

- Allport, G. W. (1961). Pattern and grouth in personality. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston.

- Berry, J. W. (1997). Immigration, acculturation and adaptation. Applied psychology: An international review, 46(1), 5-34.

- Berry, J. W., Poortinga, Y. H., Segall, M. H., & Dasen. P. R. (1992). Cross-cultural psychology: Research and applications. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Boyko, V. V. (1996). The energy of emotions in communication: a look at yourself and others. Moscow: Filin.

- Bublik, M. (2013). Psychosemantic space of ethnic identity of youth. Bulletin of the Samara State University, 2(103), 181-187.

- DeRider, R., & Tripathi, R. (1992). Norm violation and intergroup relations. Oxford: Clarendom.

- Giles, H., Bourhis, R. Y., & Taylor, D. M. (1977). Towards a theory of language in ethnic group relations. Language, ethnicity and intergroup relations. London: Acad. Press, 307-348.

- Gudykunst, W. (1995). Anxiety/Uncertainty Management (AUM) theory: Current status. In R.L. Wiseman (Ed.) Intercultural communication theory. Thousand Oaks. CA: Sage.

- Islam, M., & Hewstone, M. (1993). Dimensions of contact as predictors of intergroup anxiety, perceived outgroup variability, and out group attitude. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 19, 700-710.

- Podgoretski, J., & Gabdulhakov, V. (2014). Social communication and an effective teacher. Scientific journal ‘Education and self-development’, 1(39), 178-183.

- Soldatova, G. U. (2003). Workshop in psychodiagnostics and personality tolerance study. Moscow: Moscow State University Media Center.

- Stephan, W. G., & Stephan, C. W. (2001). Improving intergroup relations. London: Sage Publications.

- Tajfel, H., & Turner, J.C. (1986). The social identity theory of intergroup behaviour. In S. Worchel, W.G. Austin (Eds.) Psychology of intergroup relations (7-24). Chicago: Nelson-Hall.

- Triandis, H. C. (2002). Odysseus wandered for 10, I wondered for 50 years, Online Readings in Psychology and Culture, 2(1), 1.

- Zhigalova, M. P. & Gabdulhakov, V. F. (2013). Modern technologies of training in adult education. Training handbook. Brest: Brest State University, Pushkin.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

05 September 2018

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-044-0

Publisher

Future Academy

Volume

45

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-993

Subjects

Teacher training, teacher, teaching skills, teaching techniques

Cite this article as:

Gabdulkhakov, V. F., & Shishova, E. O. (2018). Multicultural Training Of Future Teachers In The Context Of Ethnic Tensions. In R. Valeeva (Ed.), Teacher Education - IFTE 2018, vol 45. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 651-660). Future Academy. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2018.09.76