Abstract

The aim of this article is to present the partial findings from a doctoral research that examined mapping emotions and feelings while maintaining contiguity with materials, as opposed to developing images in the artistic work. The research deals with the inner system performed by the creator when creating art. Touching materials is a domain associated with early childhood, and even as a sign of developmental regression, since images are associated with higher development. The uniqueness of this research suggests that maintaining contiguity with materials is essential for inner integration and self-fulfilment in the here and now, whereas cognitive images cannot achieve this aim. The research was conducted according to the qualitative phenomenological approach, and employed self-reports and semi-structured interviews about the experience of the creative process. 25 educational studies students aged 25-40 participated in the research. Data were collected using content analysis and categorization and yielded two major themes and four related categories. The findings suggest that touching material is essential for evoking bodily emotions and transforming negative emotions into positive ones. Additionally, the findings suggest that self-fulfilment depends on bodily emotions. In the current technological era, while a lot of funds are invested in cognitive development, this research shows the significance of maintaining congruity with materials to promote educational processes.

Keywords: Contiguity with materialsartistic processbodily emotionscuriositymeta-emotionmaterial and emotion

Introduction

This article presents one topic from a recent study that examined the mental system that functions within the creator during the creation of art. The current presented topic is the meaning of contiguity with materials; the article aims to provide a new perspective on the actions on materials and their meaning for the self. Contiguity with materials means acting on materials with the intention to sense the material without any outcome nor developing any image. The focus is on the sensory experience when touching material and acting on it. The research examined, among others, the emotional meaning of acting on material within the artistic process, and its relation with the self.

Problem Statement

This section presents the topics that relate to the artistic process and the topic of emotions, upon which the current research was based, and shows the gap in knowledge in Art Therapy.

Developmental understanding

Contiguity with materials is a developmental stage of the infant, termed the ‘autistic-contiguous position’ (Ogden, 1989). It appears in the very first months as the child touches with their mouth, hands, feet-surface sensation (Ogden, 1989) all they find in the outer world, a very sensory stage of getting familiar with the world. The autistic-contiguous position is the first stage of full concentration on that sensory experience. Additional perspectives extend sensing material together with inquisition, and describe it as a response to the environment with pleasure and arousal of the senses, occurring at the age from birth and up to two years (Williams & Wood, 1977). This is a stage in which there is pleasure of movement and interest in how material moves and feels (Golomb, 1990), and an investigation and experimentation with materials (Hartley, Frank, & Goldenson, 1961). Piaget and Inhelder (1971) called this stage the sensorimotor stage, wherein infants gain knowledge about the environment through the body in trial and error.

Since this ability to sense and investigate materials on their sensory aspect appears very early in childhood, its appearance later in life is perceived as a regression to early unfinished conflicts in the early developmental stages.

This perception is based on a hierarchical order (Noy, 1999) in the development of the individual, as a linear path moving from one stage to the other, regressing only when the stage is unfinished.

A very different perspective will arise if the development of the individual will be metaphorically understood as a growth of a tree, and not as a linear path committed to one direction (Heymann, 2016).

The metaphor of a tree shows that the roots, as the first to develop, continue to develop parallel to the growth of all other developing parts. Noy (1999) described the primary processes that are first developed and relate to the sensory experiences of the first developmental stages, and the secondary processes that develop later on and consist of a cognitive ability, as two cooperative developmental powers, always present, relevant and active. The primary processes are responsible for the connection with the subjective self, and the secondary processes are responsible for the adjustment and connection with the outer world, both complete an inner integration when operating. With this idea, Noy (1999) suggests a revision of the hierarchical perception of these two kind of processes. In art, according to Noy, these two processes express their alternate function.

Emotions

Two main perceptions about emotions are the core-affect (Russell & Barrett, 1999) and the basic emotions. The core affect presents all emotions as a phenomenon that relate to a basic sense of pleasant and unpleasant. The emotions are placed around an intensity axis of pleasant and unpleasant and activation and deactivation (Russell & Barrett, 1999). The perception of basic emotions (Plutchik, 2003; Izard, 2007; Lazarus, 1994; Lewis, 2008; Ekman, 1999) points to a group of emotions described as survivalist, first developed. The basic emotions are described as the main ‘atoms’ from which the other emotions ‘molecules’ are compound (Plutchik, 2003) and as the units that collect into schemata – a compound of emotions (Izard, 2007). According to this perception, the emotions are placed upon a developmental axis and not an intensity axis. The basic emotions are first to develop from birth to 15 months (Lewis, 2008). The non-basic emotions are found to be gathered under the term of self-conscious emotions, which are later developed (Lewis, 1995), and relate to the differentiation between ‘me’ and ‘not-me’. Self-conscious emotions are connected to identity (Tracy & Robins, 2004)

The connection between the emotions, and the primary and secondary processes given by Lazarus (1991) connects the basic emotions with the primary processes, and the self-conscious emotions with the secondary processes.

The Artistic Process and the gap in knowledge

An artwork is consisted of material and form, placed in space and made during time. The artistic process may be observed as a process sprawled between two poles. One pole is the material with no image at all, but pure sensing and experiencing, images and form are not in focus. The other pole is the image, where the creator’s intention is fully focused on image and meaning, as well as narrative (Lusebrink, 1991; Schaverien, 1999; Heymann, 2015). The artistic process moves back and forth between these poles, mostly ends in the image/narrative pole. In the midway between the poles, the material serves the image, as the creator, in order to create the image, must touch the material and act upon it. In the pole of image, the material is not in focus anymore.

Thus, material and form are the main components of art. The forms are images that accumulate into composition, narrative and meaning (Heymann, 2015). In art therapy, the artistic process is described as moving between the sensory-kinesthetic level to the cognitive-symbolic level (Lusebrink, 1991; Hinz, 2009), or between investment in the material and the diagram image (Schaverien, 1999). However, the analysis of the artistic process within art therapy is rare, despite the fact that the artistic process is the core of art therapy. Models that connect emotional-psychological meaning with the artistic process itself as an empiric phenomenon are rare within art therapy. The emotional content that the artistic process provides for the creator is not researched,

Research Questions

The first research question in the current research, was what emotions emerge in the artistic process and what are their implications? The article refers to this research question.

Purpose of the Study

The aim of this study is to reveal the affective content stimulated by the artistic process. This article presents the affective content of the contiguity with materials.

Research Methods

The research utilized the descriptive phenomenological psychological method (Giorgi, 1997, 2007), investigating the phenomenon-experience of the creator when creating art, and trying to create a psychological pre-transcendental notion (Giorgi, 2012), in form of a theory and a model. 25 young adults (ages 23-40) participated in the study, they created in two sessions and provided self-reports in various tools: free dictating self-report (Broome, 2011), open-ended questionnaires, self-administered grid, and interviews.

The self-administered grid is a self-report research tool developed for the investigation of the emotional meaning of the artistic process, following a pilot study that revealed that emotion expressions are not easy to achieve. Subjects tend to describe thoughts and actions, but rarely emotions (Stein, Hernandez, & Tarabasso, 2008). The self-administered grid is a table divided to three columns vertically and to numbered cells horizontally. The first column is for the chronological actions and thoughts building the artistic process, the second column is for dictating the emotions matched to the context in actions. In the third column, the subjects were invited to assign their attention laid upon the being created work of art in points of 0-5. This division of actions and emotions is based on the phenomenological approach of ‘noema’ and ‘noesis’ (Moustakas, 1994).

A list of emotions accompanied the self-administered grid, to assist emotions expression, which are familiar to the subjects but found not easy to recall.

The researcher personally interviewed the subjects to collect further data about the experience and to verify the findings analysed from the other self-report tools.

The aim was to follow emotions that emerge in all parts of the artistic process in connection to material and image. The pilot study showed that adults that are asked to create art tend mostly to create images, and the experience of sensing the material is not so easy to meet when they create freely. Therefore, the first part of the first session was constructed to be guided towards material, asking the participants to choose either clay or finger paints, and to direct their attention not to create images but to sense the material. They were asked to revert their focus from coincidental emerging of images – towards material. After receiving the instructions, the participants worked for ten minutes and immediately after experiencing the material, they filled the self-administered grid. The session went on with free creating and free material choice, then again filling in the self-administered grid.

The second session was completely free, followed by the individual free self-reports and questionnaires.

Data analysis was conducted after reading all data and by sorting data pieces and instances into meaning units (Broome, 2011). Frequencies of occurrence of emotions were calculated to give a measure of the appearance of emotion types in each artistic action. Triangulation was conducted between the self-administered grid, the free self-reports and the interviews. A pilot group of 30 students of similar ages showed similar results.

For this analysis, the discrimination into units of meaning was conducted with an experienced therapist.

Findings

The research shows two main findings with regard to the emotional content of the artistic process. The first finding presents the emotion groups, the second finding shows a difference in emotions that arise by or coincide with actions on material, and emotions that arise by or coincide with acting on image.

Acting on material means the contiguity with the material with the intention of sensing the material and not developing an image, while acting on an image directs to the intention of developing an image or to express an idea.

The emotions that emerged in the artistic process

The main difference between the main emotion units was the presence or absence of the awareness to an ‘other’. This is an aspect suggested by Lewis (2008), dividing emotions to basic emotions where there is an absence of differentiation between ‘me’ and ‘not-me’, and self-conscious emotions that are based on the ability to differentiate between ‘me’ and ‘not-me.’

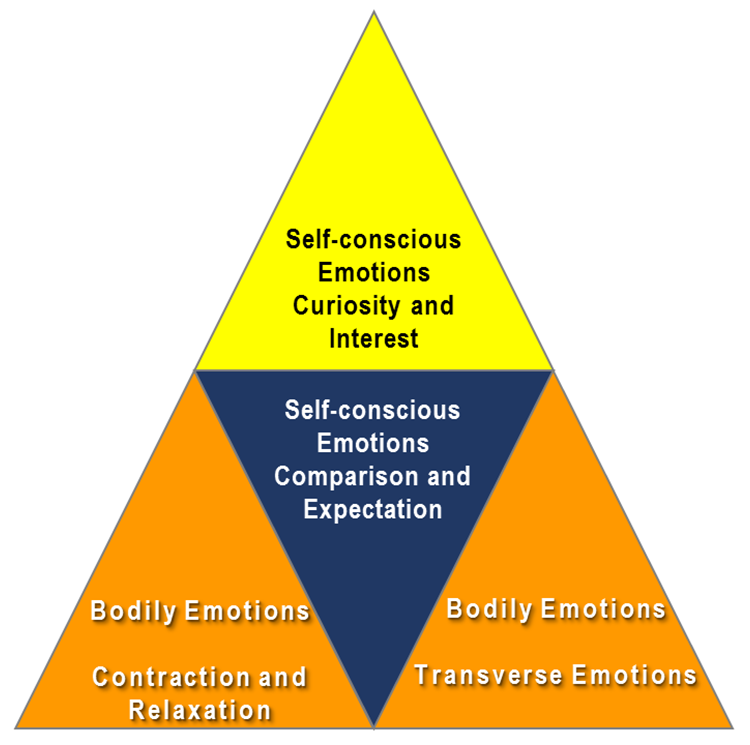

The bodily emotions unit was divided into two clusters according to the ‘movement’ of the emotions – the emotions of contraction and relaxation, and the transverse emotions that expand until over flowing.

The second emotions unit is parallel to the self-conscious emotions and divided into two clusters – emotions that are the result of expectation and comparison, and emotions that belong to interest and curiosity.

The emotions that arise by actions on material or on image

The research investigated which emotions arise by which actions, on material or on image. The analysis shows that acting on material with the dominance of sensing the material arose mostly bodily emotions (80% frequency of occurrence).

In addition, it was found that these emotions could be transformed during the acting on material, for example, it could start with fear or repulsion and when the creator continued working the emotional experience could change to joy.

“It was dirty, I was tired, I felt helpless and disgust. But I immersed myself into the material and squeeze it, I felt enjoyment and relief.”

“I felt uncomfortable and overflowed by the outcome and ambivalent emotions, but taking the clay in the hand brought me back to lightness and release.”

When acting on images, 55% self-conscious emotions and 45% bodily emotions emerged, as most of the bodily emotions were bounded with the self-conscious emotions or with images and thoughts and therefore were not ‘independent’ and free to be transformed.

Example reports on self-conscious emotions bounded with bodily emotions:

“Something started to form and curiosity was arising about the forming material, pleasure accompanied that.”

“I was pleased with the depth that came back to me from the paper. The way it absorbed the paint but not made it disappear assured me and I enjoyed the shades that were created.”

“I started to feel repulsion towards the creation and embarrassed by what I’m creating.”

Moreover, when analysing what enabled important turning points in the artistic process in the sense of influencing the art-work to become meaningful for the self, the material – its qualities, unexpected behaviour and the fortuity that it enables – was found to be the cause (76% frequency of occurrence).

Planning, cognitive thinking, and ideas were rarely the cause for turning points. All these were part of the artistic process but were rarely present as a cause of a meaningful change or development. This fortifies the free self-investment within the materials as a crucial element of an artistic process, but also of the contact with the self.

Most participants stated in the interviews that the guidance to work on material with no outcome released them from the fear of what they were going to create and how it will be seen, and gave them a feeling of joy and enthusiasm. Most participants expressed great relief to meet this exercise at the beginning. This also shows how releasing the action on materials can be. Moreover, the research showed that the ability to immerse in materials enabled an entrance to the meta-emotion zone.

Meta-emotion

Meta emotion is a different emotion from the emotions mentioned above, and was described by the subjects with many words trying to grasp it. It can be perceived as the emotion of being one with oneself, unified, fulfilled, integrated. In the research, two participants stayed in the experience of meta-emotion and worked within this emotion that is within the meta-emotion zone: “all of my being was that it is in such a magical place, that I entered inside a world. The experience is imaginary. Yes, I do see. So any shape that I made with my hands created like another part for me from this whole world that I, from that place. That is, it is all together, Like, it really seems like a muse to me. Like, I’m pretty indifferent... just all the time such release and relaxation.”

Several subjects reached the entrance into the meta-emotion zone, but stepped back: “As if every time I had a moment to linger or to stay in it, then immediately there was this sort of jolt like, wait a minute, what are others doing?”

Observing and analyzing the experience in the meta-emotion zone showed that it is conditioned by the ability to immerse in material and achieving a deep relaxation.

An artistic process that occurs within the meta-emotion zone was found to be a therapeutic experience, where inner conflicts may be worked out free of the heavy emotions these conflicts create within the self: “I weaved it as a basket like, now I wrap it with cobwebs. It shrinks like, becoming small and cramped. I mean, it’s more connected I think to not so good emotions. It’s like scary, it’s like stressful a bit, it’s suffocating, as if in principle. But, it is so not what I felt while I sculpted it.”

This might suggest that the therapeutic experience in the meta-emotion zone leads to their unravelling. This fortifies again the significance of acting on materials for the well-being and self-integration of the artist.

Curiosity

Curiosity was the only present self-conscious emotion that appeared when acting on material. It appeared on the border between sensing and awakening to the outside world. Since curiosity consists of awareness of an ‘other’, the researcher attributed curiosity to the self-conscious emotions group.

Curiosity was found to be very close to the bodily emotions, but shifted the focus and eventually the artistic process towards development and intertwining with the outer world. This emotion was found as a main self-conscious emotion when working on image, and seems to be the key emotion between the inner world and the outer world, between the bodily emotions and the self-conscious emotions, between material and form/image.

Verbal expressions of emotions

The bodily emotions evoked by acting on material are felt either as contraction or relaxation, either as contained or overflowing. Because of the direct contact between the actions and the emotions, without a complex cognitive mediator (as when the bodily emotions appear with the self-conscious emotions), there is a great opportunity to learn to differentiate between emotions. In the research, therapists that participated in the second part of research interviewed clients after experiencing acting on materials about what they felt during the work, by recalling each action and operation. They wrote in the questionnaire and also noted in the interview their positive experience about what this attentiveness to different emotions and their expression in the body brought for the client and the relationship. When acting on image, these bodily emotions come together with the threat of identity, but when acting on material the creator meets them in a more ‘pure’ manner. Acting on material following by attentiveness to what emotions were there develops the ability not only to contact these emotions and to revive them but also to study their appearance, their movement, their intensity and therefore also their regulation.

Discussion of findings

The bodily emotions follow most of the characteristics that Ekman gave to basic emotions. Since the basic emotions are the 6-8 emotions (Plutchik, 2003; Lewis, 2008) of anger, happiness, sadness, disgust, fear as universal and anticipation, surprise (Plutchik, 2003), the research termed the emotions that were found as not including the awareness of an ‘other’ – the ‘bodily emotions’. The perception of these emotions that originated in the core affect (Russell & Barrett, 1999) of pleasant/ unpleasant meets the core of being secure or unsecured, which exists in the bodily emotions, especially in the cluster of contraction versus relaxation. This suggests a hierarchy of the emotions, leading always to the bodily emotions of contraction and relaxation, of being secured or unsecured, reflected in the direct reaction to pleasant or unpleasant sensation. For example, when a transverse emotion is overflowing it feels unpleasant, then unsecure, therefore evokes the contraction bodily emotions. The bodily emotions compound with self-conscious emotions show the same chain. For example, a self-conscious emotion, which feels unpleasant, may create a sense of insecurity for the identity and evokes the contraction bodily emotion. This way is for the positive sensed emotions as well. Since the self-conscious emotions include the awareness of an ‘other’, they refer to a differentiated identity as ‘me’ (Tracy & Robins, 2004), and the bodily emotions refer to a wholeness experience of being.

This experience is the experience of merger, a fundamental experience in the human developmental path (Winnicott, 1971) but an important experience for deep relaxation, feeling ‘as one’, and connecting with the mind-body. Fears found to be aroused when acting on material were related to fear of not knowing – getting lost and disappearing, as well as the fear of getting dirty and losing control. Relaxation and joy that arose were related to not expecting results, immersing in sensation, and letting go. On the one hand, merger may create a deep relaxation within the self and the emotion of being unified. On the other hand, it may evoke the fear of disappearing, getting lost and losing control, recalling the existentialist fear of death (Yalom, 1980; Rank, 1978), fear of being shattered into pieces lost in the un-formalized universe, and fear of not-being. In contrast to this merger experience and the bodily emotions it provides, stands the experience of differentiating the self-identity when acting on images and evoking the self-conscious emotions leading to separation. The self-conscious emotions are the emotions related to identity (Tracy & Robins, 2004) and were found to be bounded with the survival bodily emotions, which shows the survival aspect of the identity – the fear regarding identity. The bodily emotions that appear with the self-conscious emotions, still emerge since creating the image is done through acting on material, but also emerge because of the survival anxiety regarding identity. This anxiety recalls the second existentialist fear – the fear of life- of becoming an isolated individual (Rank, 1978; Yalom, 1980), and a fear of being ‘not good’.

The analysis of what the subjects called ‘beautiful’ shows ‘ugly’ as chaos, and ‘beautiful’ as order and meaningfulness. Chaos, was also termed by the subjects as ‘childish’. Chaos is connected with the material, and order and meaning with images.

This shows how closely related the bodily emotions of release and relaxation are to the bodily emotion of the existential fear when acting on material, which strengthens their ability to block each other or to be transformed. Chaos and meaninglessness relate to acting on material, as order and meaning relate to the actions on images.

Both the merger experience and the differentiated experience are important for the creation of art, and for the creation of self-actualization and self-integration.

These findings fortify the ever-growing tree metaphor and Noy’s (1999) ideas about the active lively mutual function of the primary and secondary processes in the artistic process and for self-integration.

The meta-emotion was mentioned by Noy (2013), who pointed to meta-emotion as the emotion one feels when observing a work-of-art reflecting the sense of integration. The meta-emotion was rarely fully experienced, and was often found to be blocked. The fear to immerse has a main function by blocking the entrance to the meta-emotion zone, which strengthens the significance of acting and experiencing materials for entering the therapeutic zone of the meta-emotion.

Curiosity as interest is an emotion attributed to basic emotions by Izard (2007), because of its natural-kind, and survival aspect. However, concluding the sense of an existence of an ‘other’, the research joined curiosity to the self-conscious emotions unit. Curiosity as a neutral emotion (Cecchin, 1987) serves as the key to open the interaction and intertwining of the inner world with the outer world, and originates very lightly and pure when acting on materials.

The ability to differentiate between different emotions helps to regulate emotions (Russell & Barrett, 1999) especially the negative emotions, those felt as contraction or as over flowing within the emotional system.

Conclusion

Bodily emotions emerging in the artistic process when acting on material are signifying an existence in a kind of merger, which can be allowed or blocked depends on the intensity of the fear of death, of disappearing, of immersing in the endlessness. The ability to experience merger is important for experiencing intimacy within the self or with an ‘other’. The axis between merger and separation exists within the potential space (Winnicott, 1971; 1990) which is the space where creativity occurs. One may then perceive the artistic process as a process that moves back and forth between merger and separation, but still in the direction of separation as the artistic process runs into its completion (Heymann, 2016). The quality of merger is essential for this process. The researcher suggests to see the emotional system as built out of two channels that lead in different directions, but at the same time cooperate together towards the self-integration. The first channel, termed the devotedness channel, is the channel of bodily emotions that emerge when acting on materials, as primary processes that provide experience, and that is close to merger. The second channel, termed as the separation channel, is the channel of self-conscious emotions, emerging when acting on images, as secondary processes directing to the differentiation of identity. The devotedness channel, though often perceived as regressive, is actually active and essential and not regressed at all in the full experience of the artistic process, which cannot exist and develop by the separation channel only, and maybe in the life of the here and now.

Bodily emotions are termed close to basic emotions but present a wide range of emotions, being unaware of the existence of an ‘other’ and being related to survival. This research shows that these emotions appear mostly and most ‘purely’ when acting on material, with the intention to sense the material and avoid the focus on images. Sensing material with no outcome was found to revive and contact these emotions and the devotedness channel, and also transforming these emotions from contraction to relaxation and from overflowing to being contained. Perceiving sensing material as merely regressive or a reconstruction of initial primary developmental stages, misses the idea of a lively existence on the here and now, searching and building again and again the inner self integration and self-fulfillment. Contiguity with materials in adult life is crucial for achieving self-integration by letting the primary processes act, connecting oneself with the subjective lively inner world, serving in cooperation with the secondary processes that lead to separation. Regulation of emotions, which is essential for well-being, is possible when experiencing these bodily emotions and their quality of contraction versus relaxation or overflowing versus contained, learning their differentiation and movement, as experienced by touching materials. The bodily emotions, as the devotedness channel emerged when acting on materials, relate to the experience of ‘being alive’, and the self-conscious emotions, as the separation channel with the bodily emotions together that appear when acting on images, relate to the experience of becoming an identity, both complete a full range of ‘being’ and ‘becoming’ (Ashbach, 2005) within the self.

The movement between the bodily emotions revived within the material, and the self-conscious emotions emerging when creating images, activates the whole emotional system to be alive, active and in movement of change which means a fulfillment of the inner life and the self.

If sensing materials freely, with no plan or towards no outcome is perceived as undeveloped, regressive, or belonging to early life, what place does it get in education and even in adult-life? This question fortifies as using screens, a non-materialistic experience, becomes dominant even in early ages.

Coming back to the tree metaphor, the material and the emotional devotedness channel represent the roots – the first to develop but continue developing throughout, so the bodily emotions are alive and revived as the roots of the emotional system. The development of image through acting on material construct the body of the trunk that carries the branches leading to the fruits that represent images and narratives. The closer one comes towards the fruit, the less the root and trunk material will be found. What will happen to a tree that first developed its roots, then went on to develop all the rest, but does not act again on the roots? How will such a tree be able to spread more branches and fruits, and if it did, how will it carry it all with forgotten roots?

References

- Ashbach, C. (2005). Being and becoming. In Stadter, M., & Scharff, D. E. (Eds.), Dimensions of Psychotherapy, Dimensions of Experience: Time, Space, Number and State of Mind. United Kingdom: Brunner Routledge.

- Broome, E., R. (2011). Descriptive phenomenological psychological method: an example of a methodology section from a doctoral dissertation. Saybrook University. San Francisco, California.

- Cecchin, G. (1987). Hypothesizing, circularity, and neutrality revisited: An invitation to curiosity. Family Process, 26(4), 405-413.

- Ekman, P. (1999). Basic emotions. In Dalgleich, T., & Power, M. (Eds.), Handbook of cognition and emotion, 45-60. New York: John Wiley & Sons Ltd.

- Giorgi, A. (1997). The theory, practice, and evaluation of the phenomenological method as a qualitative research procedure. Journal of Phenomenological Psychology, 28(2), 235-260.

- Giorgi, A. (2007). Concerning the phenomenological methods of Husserl and Heidegger and their application in psychology. Collection du Cirp, 1, 63-78.

- Giorgi, A. (2012). The descriptive phenomenological psychological method. Journal of Phenomenological Psychology, 43(1), 3-12.

- Golomb, C. (1990). The child’s creation of pictorial world. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Hartley, R. E., Frank, L. K., & Goldenson, R. M. (1961). Understanding children’s play. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Heymann, H. R. (2015). Material-form-narrative: The artistic process as a basis of a model of evaluation in art therapy. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 209, 234-239.

- Heymann, R. H. (2016). The link between the art process and primary/secondary processes, merger/separation process and discrepancies between actual/ideal ought-to-self. Academic Journal of Creative Art Therapies, 6(2), 387-401.

- http://ajcat.haifa.ac.il/images/dec_2016/Ronithah_Heymann_article_english_formatted.pdf

- Hinz, L. D. (2009). Expressive therapies continuum: A framework for using art in therapy. Routledge.

- Izard, C. E. (2007). Basic emotions natural kinds, emotion schemas and new paradigms. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 2(3), 260-280.

- Lazarus, R. S. (1991). Emotion and adaptation. Oxford: Oxford university Press.

- Lazarus, R. S., & Lazarus, B. N. (1994). Passion and reason. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Lewis, M. (1995). Self-conscious emotions. American Scientist, 83(1), 68-78.

- Lewis, M. (2008). The emergence of human emotions. In Lewis, M., Haviland-Jones, J., & Feldman, L. B. (Eds.), Handbook of emotions, 304-219. New York: Guilford Press.

- Lusebrink, V. B. (1991). A system oriented approach of the expressive therapies: The expressive therapies continuum. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 18, 395-403.

- Moustakas, C. (1994). Phenomenological research methods. London: Sage Publications.

- Noy, P. (1999). Psychoanalysis of art and creativity. Tel Aviv: Modan.

- Noy, P. (2013). Art and emotion. International Journal of Applied Psychoanalytic Studies, 10(2), 100-107.

- Ogden, T. A. (1989). On the concept of an autistic-contiguous position. The International Journal of Psychoanalysis, 70, 127.

- Piaget, J., & Inhelder, B. (1971). Mental imagery in the child. New York: Littlefield Adams.

- Plutchik, R. (2003). Emotions and life. Washington DC: American Psychological Association.

- Rank, O. (1978). Will therapy. New York: W. W. Norton & Company.

- Russell, J. A., & Barrett, L. F. (1999). Core affect, prototypical emotional episodes, and other things called emotion: Dissecting the elephant. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 76(5), 805-819

- Schaverien, J. (1999). Revealing the image. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

- Stein, N. L., Hernandez, M. W., & Tarabasso, T. (2008). Advances in modeling emotion and thought: the importance of developmental, online, and multilevel analyses. In Lewis, M., Haviland-Jones, J., & Feldman, L. B. (Eds.), Handbook of emotions, 574-586. New York: Guilford.

- Tracy, J. L., & Robins, R. W. (2004). Putting the self into self-conscious emotions. Psychological Inquiry, 15(2), 103-125.

- Williams, G. H., & Wood, M. M. (1977). Developmental art therapy. Baltimore: University Park Press.

- Winnicott, D. W. (1971). Playing and reality. New York: Routledge.

- Winnicott, D. W. (1990). The maturational processes and the facilitating environment. London: Karnac Books.

- Yalom, I. (1980). Existential psychotherapy. New York: Basic Books.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

28 June 2018

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-040-2

Publisher

Future Academy

Volume

41

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-889

Subjects

Teacher, teacher training, teaching skills, teaching techniques, special education, children with special needs

Cite this article as:

Heymann, R. H. (2018). Back To Material: The Importance Of Touching Material For Promoting Self-Fulfillment. In V. Chis, & I. Albulescu (Eds.), Education, Reflection, Development – ERD 2017, vol 41. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 361-374). Future Academy. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2018.06.43