Abstract

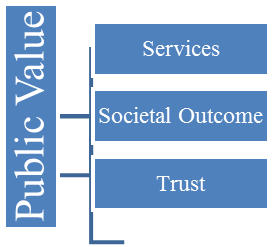

Public value is relatively new and important concept for public sector organizations and it is considered that there is no more important topic in public administration and public policy than public value. The goal of all sectors of the economy, public and private, is to create or increase the value, created by their contribution. Citizens pay taxes to the government and in return, they expected more benefits, respect and extra care of their rights at public offices. The major focus of public value research is on the dimensions of public value. Despite all the optimism, however, the concept of public value has not yet gained a consensus, being used by most authors as an unproblematic, everyday concept that can be used fruitfully in theory and practice. This lack of consensus emphasizes to develop comprehensive dimensions of public value which completely represent the Pakistani public sector. Current study determines the dimensions of public value on the basis of Kelly’s framework of sources of public value through Systematic literature review. On basis of this literature review, it is revealed that services, societal outcome and trust are the comprehensive dimensions of public value in public sector organization of Pakistan. These dimensions not only aim at enhancing efficiency and performance of the public sector but they also seek to transform the culture of traditional public administration into a flexible, market-driven and result-oriented one.

Keywords: Public ValuePublic OrganizationServicesSocietal OutcomeTrust

Introduction

It is now widely recognized that government must invent a radically different way of doing business in the public sector. The public sector can no longer function in the traditional mode. The new millennium requires a more flexible institution and the emphasis must be on strategic approaches to planning. A reformed public sector therefore must be infused with new values, a higher sense of mission and purpose and be totally infused with a “spirit of new professionalism”. Moreover, standards of impartiality, loyalty to the government of the day, and integrity, have to be maintained. The belief also reinforces the Government’s commitment to programme of Public Sector Reform which will sustain those excellent principles governing public sector behavior whilst changing what is necessary to improve effectiveness, quality of service and generally heighten the level of performance of the public service.

All around the world, reform of the public sector is a common experience (Pollitt & Bouckaert, 2004). The public sector was reformed from traditional public administration to NPM and more recently towards public value management (Moore, 1995; Stoker, 2006; O’Flynn, 2007). The theme of public value is of great importance in the current development of studies on public administration (Esposito & Ricci, 2015) and research has paid greater attention to the study of public values (Bozeman, 2007; de Graaf & van der Wal, 2010; Meynhardt, 2009; Andersen et al. 2012; Fisher & Grant, 2013; Hartely et al. 2015, Sami et al. 2016). The term public value was firstly used by the Mark H. Moore in his book, Creating Public Value (1995) in which he define public value as ,“A framework that helps us connect what we believe is valuable ... and requires public resources, with improved ways of understanding what our ‘publics’ value and how we connect to them.” Having attracted very little attention the first years after publication, the concept of public value gained traction in Tony Blair’s administration during the early 2000s. From there, the concept of public value spread first to other Westminster systems, namely Australia and New Zealand, and then to Continental Europe. In Europe, public broadcasters such as the British BBC, Germany’s ZDF, and Austria’s ORF have been the most prominent appliers of public value (Diefenbach, 2011).

Kelly & Mulgan, (2002) argued that public value in an organization is constructed on three building blocks which are services, outcome and trust. The first and most important function of an organization is to provide best services to its customer or to the whole society and outcome of these services should be positive and valuable for whole society and above all trust of society or customer on the provided services and its result is most important. If the public have not trust on the organization despite the best services and positive outcome, then it will jeopardize the concept of public value. Based on the idea of (Blaug, Horner, & Lekhi, 2006) that public satisfaction is not enough to measure public value but some others features are also need to be considers like what are the expectation of public before providing them a particular service, in which way this service is provided them how they use this service. O’Flynn (2007) describes public value as moving away from the ideological position of market versus state provision. Stoker (2006) views public value as a framework for post competitive collaborative network forms of governance Constable et al (2008) defined that Public value is considered as a comprehensive approach to think about improvement in public service and public management. Public value is a contribution of an organization towards society and its way to contribute it (Colon & Guerin-Schneider, 2015).

Various proponents argue public value should be seen as a paradigm (Stoker 2006; Benington 2009); as a concept (Kelly, Mulgan & Muers 2002); a model (O’Flynn 2007). The term has been contrasted with rational choice and neo-liberal theories and with economic and individualistic theories of consumption (O’Flynn 2007). Benington (2009) contrasts ‘exchange value’ (private choice derived from neo-classical economics) with ‘public value’ that includes economic as well as social and political value. It has also been linked to related concepts such as ‘consensual policymaking’ (Marton & Phillips, 2005) and the ‘public interest’ (Bozeman, 2002). Perhaps the ambiguous nature of public value and its various applications fuels its popularity – it is all things to all people.

Bold claims and great expectations are sometimes voiced, regarding public value as an important theoretical and practical “guiding concept.” For example, public value is regarded as resolving democratic deficits in modern public administration (Benington & Moore, 2011; Benington, 2009,); it is increasingly used in administrative practice (Jørgensen, 2006); it is presented as “a hard-edged tool for decision-making” (Alford & O’Flynn, 2009,), and “a rigorous way of defining, measuring and improving performance” (Cole & Parston, 2006). Due to the focus on public values, it has been stated that we are even entering a “new era in public management” (Stoker, 2006).

Some scholars think about PVs in terms of core values, chronological ordering, or other bifurcations or dimensional distinctions (Rutgers, 2015). Others conceptualize PVs in terms of “hard” and “soft” values (Steenhuisen, 2009); individual, professional, organizational, legal, and public-interest values (Van Wart, 1998); ethical, democratic, professional, and people values (Kernaghan, 2003); political, legal, organizational, and market values (Nabatchi, 2012).

Problem Statement

Although public value concept attracts a large number of researchers, who considered it as unproblematic and everyday concept that can be used productively in theory and practice, however, after 20 years of its emergence, it could not gain a consensus (Rutgers, 2015). Researchers provided different interpretation and operationalization of the concept of PV (Van Wart and Berman, 1999; Kernaghan, 2003; Rutgers, 2008; Steenhuisen, 2009; Nabatchi, 2012). Thus literature lack on common grounds to measure the concept. For example, Anderson et al. (2012) provided seven dimensions of PV, Karunasena and Deng (2012) studied PV on five dimensions, Cresswell and Sayogo (2012) considered six PV dimensions, Thomson et al., (2014) confined to three PV dimensions while four PV dimensions were considered by Wang and Christensen (2015). Some scholars considered PV as a unidimensional construct (Page et al., 2015; Prebble, 2015; Morse, 2010; Hartley et al., 2015; Badia et al., 2014; Jaaron & Backhouse, 2010; Taebi et al., 2014). This reflect that there is no consensus on the definition and dimensions of the construct. This require a consolidation of existing literature to provide a comprehensive set of dimensions for PV that capture a broader range of concept, provided by the existing researcher.

Research Questions

Based on the problem statement the main objective of this study is to identify the possible and applicable dimensions of public value for Pakistani public sector. To achieve this objective, study formulate the research question:

Purpose of the Study

The concept of Public Value is significant for public sector administrators as stressed by Jørgensen and Bozeman, because there is “no more important topic in public administration and policy than public values” (2007, p. 355). Public value was first articulated by Mark Moore from Harvard's Kennedy School of Government in his seminal book ‘Creating Public Value - Strategic Management in Government’ (1995) as a new way of thinking about public management that might help public managers to focus on creating public value by satisfying individual and collective desires (Omar, 2015). The approach postulates that public value creation should be the main objective of public managers, analogue to shareholder value maximization in the private sector (Knoll, 2012). Public Value is a philosophy of public management in which public managers should think and act strategically to create public value and success is drawn from initiating and reshaping public sector enterprises in ways that increase their value to the public (Staples, 2010).

The underlying principle of the pubic value concept is that the value to citizens should guide the operations of public organizations on the delivery of public services (Moore, 1995). This is because the ultimate goal of public programs to create value for citizens (Moore, 1995; Try & Radnor, 2007; Meynhardt, 2009). Citizens derive value from their personal consumption of public services (Kelly et al., 2002; Alford & O’Flynn, 2009; Karunasena, 2012). The goal of all sectors of the economy, public and private, is to create or increase the value created by their contribution. Within a private sector, this goal is fairly clear to generate private value by generating a profit. Just as the goal of the private sector is to create private value, the goal of the public sector is to create public value. The term ‘public value’ can be defined as what the public values – what they are willing to make sacrifices of money and freedom to achieve (Kelly et al., 2002), and describes the contribution made by the public sector to economic, social and environmental well-being of a society or nation (Try, 2007).

This concept is becoming popular in the United States, European nations, Australia, and even in developing nations in evaluating the performance of public services due to its capacity for examining the performance of public services from the perspective of citizens (Kelly et al., 2002; Alford & O’Flynn, 2009; Benington, 2009). It is used to measures the total impact of government activities to citizens in terms of the value it creates (Kelly et al., 2002; Alford & O’Flynn, 2009). This concept is extremely useful for government to improve policy decisions and the relationship between government and citizens (Kelly et al., 2002).

The concept of public value has been extended in many different ways. Kelly et al. (2002), for example, define public value as the value created by the government for citizens through the provision of public services, passing of laws and various other government activities. Such a definition helps to identify the important sources of creating public value. Delivery of quality public services creates public value (Kelly et al., 2002; Try, 2008; O’Flynn, 2007). Achieving socially desirable outcomes is another way to crate public value (Kelly et al., 2002; Cole & Parston, 2006; Try, 2008). Effectiveness of public organisations also creates public value (Moore, 1995; Karunasena & Deng, 2012) Developing trust between the public and the government creates public value (Kelly et al., 2002). It is, argued that trust is a public value outcome rather than a source of public value creation (Grimsley & Meehan, 2007). So, the purpose of this study to find out the dimensions of public value to consolidte the concept of public value.

Research Methods

The literature reveals that there is no consensus among the researchers about the dimensions of Public Value. This study do a systematic literature review to provide a comprehensive set of dimensions of PV that capture a broader range of concept. Literature reveals that there are many kinds of public value in a society and Talbot, (2008) says that there is no singular public value but rather multiple public values. Public and governmental interaction continuously defines and redefines public value, thus, public value is not fixed and it should be continually explored and multiple values addressed through either aggregation and/or choice (Talbot, 2008). Jorgensen and Bozeman (2007), for example, develop an inventory of seventy-two kinds of public value with seven main “value constellations”: the first constellation contains values associated with the public sector’s contribution to society; the second constellation covers values associated with transformation of interests to decisions; the third constellation encompasses values associated with the relationship between public administration and politicians; the fourth constellation comprises values associated with the relationship between public administration and its environment; the fifth constellation comprehends values associated with intra-organisational aspects of public administration; the sixth constellation includes values associated with the behaviour of public-sector employees; and the seventh constellation embraces values associated with the relationship between public administration and citizens.

Kernaghan, (2003) examines about thirty-two kinds of public values under four categories that are ethical values, democratic values, professional values and people focus values in West-minister style governments including Australia, New Zealand, Canada and the United Kingdom. Quality, openness, responsiveness, efficiency, user orientation, equity, citizen’s self-development, democracy, and environmental sustainability are important kinds of public value.

Proponents of multidimensional public value argued that User Focus, Public at Large, Efficient Supply, Budget Keeping, Rule abidance, Balancing Interest, Professionalism (Anderson et al. 2012) Organizational efficiency, Quality of information and services, Openness, responsiveness, Environmental Sustainability (Karunasena & Deng, 2012) Financial, Political , Strategic, Stewardship, Quality of life, Social (Cresswell and Sayogo, 2012) Accessibility, Accountability, Performance, (Thomson et al., 2014) Environment value, Social value, Economic value, Political value (Wang & Christensen, 2015) are the important public value dimensions. While advocates of unidimensional public value claimed that public value is consist of Collaboration (Page et al., 2015; Prebble, 2015; Morse, 2010) Political astuteness (Hartley et al., 2015) Co-Governance (Badia et al., 2014) Lean Thinking (Jaaron & Backhouse, 2010) innovation (Taebi et al., 2014). Detail of these dimensions is illustrated in Table

Findings

The current study categorized the components of ‘public value’, considering specific nature and requirement of public sector organizations of Pakistan. These components are delivery of quality public services, socially desirable outcome and development of public trust in government as presented by Kelly et al. (2002) framework for public value. Most of the previous work on dimensions of public value overlook one or two components of Kelly et al. (2002) framework. For example, seven dimensions presented by Anderson et al. (2012), cover two components of public value that are services and trust but the component of outcome was overlooked in their work. Karunasena and Deng (2012) describe services and outcome but Trust is missing. Similarly, Wang and Christensen (2015) focus on outcome and trust but service is overlooked. This pertain a gap in literature to cover broader components of the concept of public value presented by Kelly et al. (2002) in general. To fill this gap, the current study combining the dimensions as discussed in Table

Table

Services

Services is about the provision of quality services in a user friendly manner in order to satisfy users and public needs (Jorgensen & Bozeman, 2007; Karunasena & Deng, 2012). The fundamental purpose of government departments is to provide services to satisfy public needs. The existence of any institution is directly linked to its purpose (Slater & Aiken, 2015). Public institutions, with different resources, deliver specific and general services which members of the public cannot provide in an individual capacity. In providing such services, public institutions aim to improve the general welfare of society. The delivery of services is therefore, the overall responsibility of government departments. Any endeavor to meet the basic needs of the public must be driven by the ‘people first’ approach. Public institutions are obligated to provide equal services to all citizen, Consulting with citizens about the services they are entitled to receive, Information sharing on the quality of services to be provided, Considerate and courteous treatment of the public, Transparency on how government departments are managed, Accountability for quality service provision and Responsibility for providing efficient, effective and economic services.

It places much importance on concern for people as well as striving for common goals which is essentially the underlying purpose of public institutions. Employees of public institutions are obliged to treat people with respect, dignity and care. Further, the public has a legitimate right according to the tenets of democracy to receive quality services. Therefore, while government departments are not only responsible for the purpose of their existence, they are also accountable to the public in executing their responsibilities (Dorasamy, 2010).

Societal Outcome

Individuals play a key role in the workplace (Khan et al., 2014; Khan et al., 2016; Qureshi et al., 2014; Qureshi et al., 2015; Qureshi et al., 2016; Yasir et al., 2017). Societal outcome refers to individuals’ belief that they can contribute to the welfare of other people and society through their job. it refers to an emotionally driven understanding that one’s work matters to others (Mayer, 2017). Research on relational job design (Grant 2008) shows that beneficiary contact is a predictor of greater prosocial impact because interaction with specific other people visualizes how one’s actions make a difference in other people’s lives. This is particularly relevant in public service organizations, in which most services are performed at the front line in interaction with users and clients. Interaction with users makes it vivid for public service employees how their job contributes to the well- being of individual users. In this respect, perceived societal impact serves as an availability heuristic for connecting the cues provided by the day-to-day job activities of the individual employee. Thus, if employees clearly see how their job contributes to society, the effect of transformational leadership on value congruence is reinforced. In contrast, if employees are not able to imagine how their job contributes to the values espoused by the manager, the vision may be seen as simple rhetoric without a meaningful relation to employees’ day-to-day job activities. If employees do not perceive that their job impacts society, highlighting collectivistic norms and contributions to society may easily be perceived as “cheap talk” (Jensen, 2018).

Scant research has examined employees’ discretionary behaviors that target the social level or, in other words, that intend to enhance the well-being of their organization’s stakeholders, including the natural environment (Crilly et al. 2008; Daily et al. 2009; Vlachos et al. 2014). Accordingly, (Roeck & Farooq, 2017) examine societal outcome by employees’ engagement in green behaviors, including employees’ actions to perform work in an environmentally friendly way (e.g., recycling, rational use of resources, participation in environ- mental initiatives, setting of more sustainable policies), and societal behaviors, including employees’ actions that support overall community well-being even outside the work context.

Raineri and Paille ́ (2016) show that employees who perceive their organization as engaged in environmental policies are more likely to follow its lead by demonstrating more environmental citizenship behaviors (Roeck & Farooq, 2017).

Trust

Trust means that the customer believes that an organization acts in his/her best interests because of the goals and values shared by the organization and the customer (Doney & Cannon, 1997). According to Doney and Cannon (1997), trust was defined as the “perceived credibility and benevolence of a target of trust” (Noh, 2010). Trust is an expectation that a person or entity will behave as desired under conditions of risk (Yasir et al. 2016).

A relationship based on trust between the organization and its customers is a organization’s key competitive element (Lee & Park, 2008; Lee & Lee, 2010). The object of the trust includes a person, an organization, a product, or an idea (Chung, 2012). Trust is key to maintaining economic and transactional relationships between a company and its customers (Hwang et al. 2014). Trust is used as an effective means that enables customers to reduce the perceived risk during the consumption of a service (Everard & Galletta, 2005).

This trust is not focused on people or groups but instead describes a level of confidence in society in general. High levels of trust mean that most people think that the system works, that systems and institutions function in a socially appropriate way, that even strangers can be expected to behave in socially appropriate ways (Nikolas, 2018).

Trust in public sector organizations is declining in many countries and concerns regarding government accountability are widespread. In addition to concerns about whether we can hold government accountable for desired policy outcomes, decreasing trust levels also re ect concerns that the actions of public administrators during policy implementation are driven by self-interest rather than the interests of the larger public or community (Wright et al. 2016).

Conclusion

This study determines the comprehensive set of dimensions of public value on basis of previous literature and according to the specific nature of public sector organizations in Pakistan. The proposed dimensions of public value in this research paper are in line with the policy of Pakistani Government. Pakistan is also following the global trend in public management reform and introduced measures akin to that elsewhere with “managing for results” as an overarching goal. These dimensions of public value not only aim at enhancing efficiency and performance of the public sector but they also seek to transform the culture of traditional public administration and new public management into a flexible, market-driven and result-oriented one. Thus the development and measurement of the public value of Pakistani public sector will indicate the capability of public sector in developing a well-rounded student.

Managerial Implication

This study will contribute in developing theoretical model of public value in Pakistani public sector and will give a clear picture to public sector employees, their managers and policy makers of Pakistani government about the true concepts of public value. This study educates the employees that how to deal with citizens, politicians, pressure groups and how to make collaboration with other agencies to achieve the desired outcome of organization and government without compromising the future generations. This study can also be used as a reference by the researchers and public policy makers of governments. Furthermore, public sector organizations need to know the required public value since this knowledge will be beneficial in helping the public administrators when developing their policies.

Impact on Society, Economy and Nation

The public value dimensions will benefit society, government and public administrators (policymakers) and nation by serving as a national indicator of the service requirements at public sector organization as well as a tool for gauging the competitiveness of public sector organizations. In addition, the result of the study can be used as a parameter for public sector employees to serve the nation in right direction in line with international standard of services.

Limitation and Future Direction

Although this study has comprehensively and systematically reviews the literature on the topic of public value and determines the dimensions that are in line with the specific nature of public sector organizations yet it has some limitations. The major limitation is that it is just a review of past literature and did not validate empirically. For future researchers, it is suggested to empirically validate this study by using some robust statistical techniques. Future researchers should also conduct this research in other countries to validate the result according to the specific nature of their public sector organizations.

References

- Alford, J., & O’Flynn, J. (2009). Making Sense of Public Value: Concepts, Critiques and Emergent Meanings. International Journal of Public Administration, 32(3-4), 171–191.

- Andersen, L. B., Jørgensen, T. B., Kjeldsen, A. M., Pedersen, L. H., & Vrangbæk, K. (2012). Public Value Dimensions: Developing and Testing a Multi-Dimensional Classification. International Journal of Public Administration, 35(11), 715–728.

- Badia, F., Borin, E., & Donato, F. (2014). Co-governing public value in local authorities. In Public Value Management, Measurement and Reporting (pp. 269-289). Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

- Benington, J. (2009). Creating the Public In Order To Create Public Value? International Journal of Public Administration, 32(3-4), 232–249.

- Benington, J., & Moore, M. H. (2011). Public value in complex and changing times. Public value: Theory and practice, 1-30.

- Blaug, R., Horner, L., & Lekhi, R. (2006). Public value , politics and public management. A literature review. Measurement, 72.

- Bogle, D., & Seaman, M. (2010). The six principles of sustainability. Chemical engineer, (825), 30-32.

- Bozeman, B. (2002). Public value failure: When efficient markets may not do. Public administration review, 62(2), 145-161.

- Bozeman, B. (2007). Public values and public interest: counterbalancing economic individualism.

- Chung, K. C. (2012). Antecedents of brand trust in online tertiary education: a tri-nation study. Journal of Global Scholars of Marketing Science, 22(1), 24-44.

- Cole, M., & Parston, G. (2006). Unlocking public value: A new model for achieving high performance in public service organizations. John Wiley & Sons.

- Colon, M., & Guerin-Schneider, L. (2015). The reform of New Public Management and the creation of public values: compatible processes? An empirical analysis of public water utilities. International Review of Administrative Sciences, 81(2), 264–281.

- Constable, S., E. Passmore and D. Coats. (2008). Public Value and Local Accountability in the NHS. London: Work Foundation

- Cresswell, A. M., & Sayogo, D. S. (2012). Developing public value metrics for returns to government ICT investments. The Research Foundation of State University of New York (SUNY), New York, 61268.

- Crilly, D., Schneider, S. C., & Zollo, M. (2008). Psychological antecedents to socially responsible behavior. European Management Review, 5(3), 175-190.

- Daily, B. F., Bishop, J. W., & Govindarajulu, N. (2009). A conceptual model for organizational citizenship behavior directed toward the environment. Business & Society, 48(2), 243-256.

- de Graaf, G., & van der Wal, Z. (2010). Managing Conflicting Public Values: Governing With Integrity and Effectiveness. The American Review of Public Administration, 40(6), 623–630.

- Diefenbach, F. E. (2011). Entrepreneurship in the Public Sector (pp. 31-64). Gabler.

- Doney, P. M., & Cannon, J. P. (1997). An examination of the nature of trust in buyer-seller relationships. the Journal of Marketing, 35-51.

- Dorasamy, N. (2010). Enhancing an ethical culture through purpose-directed leadership for improved public service delivery: A case for South Africa.African Journal of Business Management, 4(1), 56.

- Esposito, P., & Ricci, P. (2015). How to turn public (dis)value into new public value? Evidence from Italy. Public Money & Management, 35(3), 227–231.

- Knoll, E. M., (2012), The Public Value Notion in UK Public Service Broadcasting, PhD Thesis, The London School Of Economics And Political Science

- Everard, A., & Galletta, D. F. (2005). How presentation flaws affect perceived site quality, trust, and intention to purchase from an online store. Journal of Management Information Systems, 22(3), 56-95.

- Fisher, J., & Grant, B. (2013). Public Value: Recovering the Ethical for Public Sector Managers. International Journal of Public Administration, 36(4), 248

- Grant, A. M. (2008). Employees without a cause: The motivational effects of prosocial impact in public service. International Public Management Journal, 11(1), 48-66.

- Grimsley, M., & Meehan, A. (2007). e-Government information systems: Evaluation-led design for public value and client trust. European Journal of Information Systems, 16(2), 134-148.

- Hartley, J., Alford, J., Hughes, O., & Yates, S. (2015). Public value and political astuteness in the work of public managers: The art of the possible. Public Administration, 93(1), 195-211.

- Hwang, H. J., Kang, M., & Youn, M. K. (2014). The influence of a leader's servant leadership on employees' perception of customers' satisfaction with the service and employees' perception of customers' trust in the service firm: the moderating role of employees' trust in the leader. Journal of Global Scholars of Marketing Science, 24(1), 65-76.

- Jaaron, A., & Backhouse, C. (2010, February). Lean manufacturing in public services: prospects for value creation. In International Conference on Exploring Services Science(pp. 45-57). Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg.

- Jensen, U. T. (2018). Does Perceived Societal Impact Moderate the Effect of Transformational Leadership on Value Congruence? Evidence from a Field Experiment. Public Administration Review, 78(1), 48-57.

- Jørgensen, T. B. (2006). Public values, their nature, stability and change. The case of Denmark. Public Administration Quarterly, 365-398.

- Jorgensen, T. B., & Bozeman, B. (2007). Public Values: An Inventory. Administration & Society, 39(3), 354–381.

- Kanishka Karunasena, (2012). An Investigation of the Public Value of e-Government in Sri Lanka, PhD thesis, RMIT University , Melbourne, Australia

- Karunasena, K., & Deng, H. (2012). Critical factors for evaluating the public value of e-government in Sri Lanka. Government Information Quarterly, 29(1), 76–84.

- Kelly, G., & Mulgan, G. (2002). Creating Public Value An analytical framework for public service reform. Dicussion paper, Cabinet Office Strategy Unit, U.K

- Kernaghan, K. (2003). Integrating values into public service: The values statement as centerpiece. Public administration review, 63(6), 711-719.

- Omar, K. H. M., (2015). The public value of Gov. 2.0: The case of Victorian local government, Australia, PhD Thesis, Swinburne University of Technology

- Khan, M. I., Awan, U., Yasir, M., Mohamad, N. A. B., Shah, S. H. A., Qureshi, M. I., and Zaman, K. (2014). Transformational leadership, emotional intelligence and organizational commitment: Pakistan's services sector. Argumenta Oeconomica, 33(2), 67-92.

- Khan, M. M., Yasir, M., Afsar, B., and Azam, K. (2016). The Relationship between Organizational Culture and Employee Conflict: Evidence from Higher Education Institutions in Pakistan. Abasyn Journal of Social Sciences, 674-690.

- Knoll, E. (2012). The public value notion in UK public service broadcasting: an analysis of the ideological justification of public service broadcasting in the context of evolving media policy paradigms (Doctoral dissertation, The London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE).

- Lee, J., & Lee, S. E. (2010). Initial trust with unknown e-tailers in the context of online gift shopping. Journal of Global Academy of Marketing, 20(4), 343-352.

- Lee, S. H., & Park, M. R. (2008). The relationship between trust, trustworthiness, and repeat purchase intentions: A multidimensional approach. Journal of Global Academy of Marketing Science, 18.

- Marton, R., & Phillips, S. K. (2005). Modernising policy for public value: Learning lessons from the management of bushfires. Australian Journal of Public Administration, 64(1), 75-82.

- Mayr, M. L. (2017). Transformational Leadership and Volunteer Firefighter Engagement. Nonprofit Management and Leadership, 28(2), 259-270.

- Meynhardt, T. (2009). Public Value Inside: What is Public Value Creation? International Journal of Public Administration, 32(3-4), 192–219.

- Moore, M. H. (1995). Creating Public Value: Strategic Management in Government. Cambridge, MA:Harvard University Press.

- Morse, R. S. (2010). Integrative public leadership: Catalyzing collaboration to create public value. The Leadership Quarterly, 21(2), 231-245.

- Nabatchi, T. (2012). Putting the “public” back in public values research: Designing participation to identify and respond to values. Public Administration Review, 72(5), 699-708.

- Nichols, P. M., & Dowden, P. E. (2018). Maximizing stakeholder trust as a tool for controlling corruption. Crime, Law and Social Change, 1-25.

- Noh, J. (2010). The effect of forgiveness and trust on relational performance in the purchasing of business services. Journal of Global Academy of Marketing, 20(4), 294-306.

- O’Flynn, J. (2007). From new public management to public value: Paradigmatic change and managerial implications. The Australian Journal of Public Administration, 66(3), 353–366.

- Omar, K. H. (2015). The public value of Gov 2.0: the case of Victorian Local Government, Australia. PhD Thesis. Swinburne University of Technology.

- Page, S. B., Stone, M. M., Bryson, J. M., & Crosby, B. C. (2015). Public Value Creation by Cross‐Sector Collaborations: A Framework and Challenges of Assessment. Public Administration, 93(3), 715-732.

- Pandey, S. K., Davis, R. S., Pandey, S., & Peng, S. (2016). Transformational Leadership and the Use of Normative Public Values: Can Employees Be Inspired to Serve Larger Public Purposes?. Public Administration, 94(1), 204-222.

- Pollitt, C., & Bouckaert, G. (2004). Public management reform: A comparative analysis. Oxford University Press, USA.

- Prebble, M. (2015). Public value and limits to collaboration. International Journal of Public Administration, 38(7), 473-485.

- Qureshi, M. I., Iftikhar, M., Janjua, S. Y., Zaman, K., Raja, U. M., & Javed, Y. (2015). Empirical investigation of mobbing, stress and employees’ behavior at work place: quantitatively refining a qualitative model. Quality & Quantity, 49(1), 93-113.

- Qureshi, M. I., Rasli, A. M., & Zaman, K. (2014). A new trilogy to understand the relationship among organizational climate, workplace bullying and employee health. Arab Economic and Business Journal, 9(2), 133-146.

- Qureshi, M. I., Rasli, A. M., & Zaman, K. (2016). Energy crisis, greenhouse gas emissions and sectoral growth reforms: Repairing the fabricated mosaic. Journal of Cleaner Production, 112, 3657-3666.

- Raineri, N., & Paillé, P. (2016). Linking corporate policy and supervisory support with environmental citizenship behaviors: The role of employee environmental beliefs and commitment. Journal of Business Ethics, 137(1), 129-148.

- Roeck, K., & Farooq, O. (2017) Corporate Social Responsibility and Ethical Leadership: Investigating Their Interactive Effect on Employees’ Socially Responsible Behaviors. Journal of Business Ethics, 1-17.

- Rutgers, M. (2008). Sorting out public values? On the contingency of value classification in public administration. Administrative Theory & Praxis, 30(1), 92–113.

- Rutgers, M. R. (2015). As Good as It Gets? On the Meaning of Public Value in the Study of Policy and Management. The American Review of Public Administration, 45(1), 29–45.

- Sami, A., Jusoh, A., & Qureshi, M. I. (2016). Does Ethical Leadership Create Public Value? Empirical Evidences from Banking Sector of Pakistan. International Review of Management and Marketing, 6(4S).

- Slater, R., & Aiken, M. (2015). Can’t You Count? Public Service Delivery and Standardized Measurement Challenges–The Case of Community Composting. Public Management Review, 17(8), 1085-1102.

- Staples, W. (2010). Public value in public sector infrastructure procurement.

- Steenhuisen, B. (2009). Competing public values: Coping strategies in heavily regulated utility industries. TU Delft, Delft University of Technology.

- Stoker, G. (2006). Public value management: a new narrative for networked governance? The American Review of Public Administration, 36(41), 41–57.

- Talbot, C. (2008). Measuring public value. The Work Foundation, London.

- Taebi, B., Correlje, A., Cuppen, E., Dignum, M., & Pesch, U. (2014). Responsible innovation as an endorsement of public values: The need for interdisciplinary research. Journal of Responsible Innovation, 1(1), 118-124.

- Thomson, K., Caicedo, M. H., & Mårtensson, M. (2014). The quest for public value in the Swedish museum transition. In Public value management, measurement and reporting (pp. 105-128). Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

- Try, D., & Radnor, Z. (2007). Developing an understanding of results-based management through public value theory. International Journal of Public Sector Management, 20(7), 655-673.

- Vlachos, P. A., Panagopoulos, N. G., & Rapp, A. A. (2014). Employee judgments of and behaviors toward corporate social responsibility: A multi‐study investigation of direct, cascading, and moderating effects. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 35(7), 990-1017.

- Van der Wal, Z. (2014). Elite ethics: Comparing public values prioritization between administrative elites and political elites. International Journal of Public Administration, 37(14), 1030-1043.

- van Eijck, K., & Lindemann, B. (2014). Strategic practices of creating public value: How managers of housing associations create public value. In Public Value Management, Measurement and Reporting (pp. 159-187). Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

- Van Wart, M. (1998). Changing public sector values (Vol. 1045). Taylor & Francis.

- Wang, B., & Christensen, T. (2015). The Open Public Value Account and Comprehensive Social Development: An Assessment of China and the United States. Administration & Society, 49(6), 852-881.

- Warren J. Staples, 2010, Public Value in Public Sector Infrastructure Procurement, PhD thesis, Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology.

- Wright, B. E., Hassan, S., & Park, J. (2016). Does a public service ethic encourage ethical behaviour? Public service motivation, ethical leadership and the willingness to report ethical problems. Public Administration, 94(3), 647-663.

- Yasir, M., Imran, R., Irshad, M. K., Mohamad, N. A., and Khan, M. M. (2016). Leadership Styles in Relation to Employees’ Trust and Organizational Change Capacity. SAGE Open, 6(4), 2158244016675396.

- Yasir, M., Rasli, A., and Qureshi, M. I. (2017). Investigation of the Factors that Affect and Gets Affected by Organizational Ethical Climate. Advanced Science Letters, 23(9), 9351-9355.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

01 May 2018

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-039-6

Publisher

Future Academy

Volume

40

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-1231

Subjects

Business, innovation, sustainability, environment, green business, environmental issues

Cite this article as:

Sami, A., Jusoh, A., Nor, K. M., Irfan, A., & Liaquat, H. (2018). Identification Of Public Value Dimensions In Pakistan’s Public Sector Organizations. In M. Imran Qureshi (Ed.), Technology & Society: A Multidisciplinary Pathway for Sustainable Development, vol 40. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 766-779). Future Academy. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2018.05.63