Abstract

The aim of this paper is to analyze the main monetary policy shifts of central banks before and after the crisis and to see their impacts on monetary policy and communication strategies. In this regard, a number of central banks from developed and developing countries have been chosen and analyzed in terms of their monetary policy changes and especially their communication strategies. The research is based on a literature review and a holistic, multiple method case studies, drawing on websites, a primary communication tool for central banks, and on the basic reports on their websites. We also benefit from the survey commentaries of the BIS conducted in 2013. While central banks in developed economies try to minimize the negative impacts of global financial crises they started to use unconventional policies such as quantitative easing, negative interest rate policy and forward guidance. On the other hand central banks in developing countries not only try to minimize the negative impact of crisis on the economy but also deal with the negative effects of the unconventional monetary policies from developed economies. To achieve that goal, they mostly started to implement macro-prudential measures. What is common in developing and developed countries during and after the global crisis is that they increased the awareness of financial stability and established new financial stability bodies and included financial stability in their policy mix. To do this some of them has changed their law and even their organizational structure.

Keywords: Unconventional Monetary Policy StrategiesMacro-prudential MeasuresGlobal Financial CrisesFinancial Stability

Introduction

Before the global crises of 2007-2009, the challenge facing central banks and the international financial system was how to deal with the increased volatility of financial flows and exchange rates, increased uncertainty, instability of global financial environment and complexity of transactions, which are all results of global financial market (Kahveci and Sayılgan, 2006). Then the global financial crisis has engendered very significant outcomes with major implications for monetary policy. It has been very challenging for central banks to manage monetary policy and to give direction to the economy by using conventional monetary policy tools after the global crisis of 2007-2009. The post-crisis situation drove central banks to implement unconventional monetary policies to deal with the crisis and to minimize the damage to the economy. Besides, implementing unconventional monetary policies made it harder for the public to understand the future path of monetary policy, thus central banks have started to take new steps in communication strategies that are very different from previous ones (Woodford, 2013, s.96).

During this crisis era, central banks in developed countries had only one challenge to deal with: to minimize the negative impacts of crisis on the economy and to return the economy back to pre-crisis levels. To do that, they changed monetary policy strategies and started to use unconventional policies such as quantitative easing, negative interest rate policy and forward guidance. On the other hand, central banks in developing countries had to deal with at least two challenges: to minimize the negative impact of crisis on the economy and return to pre-crisis levels, and additionally to deal with the negative effects of the unconventional monetary policies in developed economies. They not only had to cope with the crisis but also had to find solutions to challenges coming from developed countries such as increasing volatility of funds and increasing risks to the financial stability, due to quantitative easing, negative interest rate and forward guidance policies. To achieve that goal, they mostly started to implement macro-prudential measures.

There is also a growing literature over recent years that attempt to evaluate the effect of the unconventional monetary policies adopted by advanced economies during the global financial crisis. However, there is still room in the literature to study all developed countries’ unconventional monetary policy spillover effects on emerging markets, and also to examine whether macro-prudential policy is significant in minimizing spillover.

Within the framework of monetary policy strategies after the global financial crises, our study focuses on the challenges faced by central banks in developed and developing economies and analyse the similarities and differences. In this context, the study begins with a literature review of financial stability, unconventional monetary policies, then will go on to analyse implementations of different monetary policy strategies of various developed and developing economies and their results. Research methodology, analyses and research model will take place at the second section. Discussions of findings and observations were included at the last section.

Literature Review and Theoretical Framework

Financial Stability

After global financial crises, central banks have come under criticism for having only one goal in terms of inflation targeting. Prior to the crisis, inflation targeting regimes, supported by independence, transparency and clear communications, had been relatively successful in achieving sustained low levels of inflation and macroeconomic financial stability through expectations management (Vayid, 2013: p.18). One of the most important lessons of the crisis, from the point of financial stability, was that micro risks were not enough to secure the goal of preserving financial system as a whole. In other words, the fact that each financial institution was stable did not mean that financial system as a whole would be stable.

However, the process that led up to the global crisis showed that focusing solely on price stability does not guarantee financial stability. The challenges faced during this period forced central banks to give more weight to the recognition, evaluation and communication of the risks and vulnerabilities. Additionally, reducing and preventing instability in the financial system and in the general economy joined the priorities of central banks. In this regard, central banks in the United Kingdom, Germany, the Czech Republic, Brazil, Russia and Turkey all started to take on a greater role in ensuring financial stability (BIS, 2013).

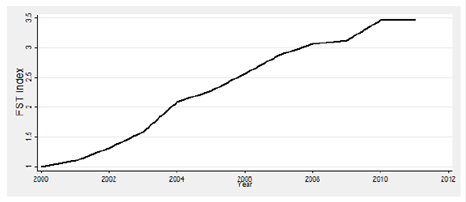

Since there is no consensus on how to define financial stability, unlike price stability, and central banks share responsibility for financial stability with other institutions, communication for financial stability is a more complicated act than it is for price stability (Siklos, 2014). The fact that financial stability has not a single accepted definition makes it harder to detect the signals of volatility or crisis that emerging at times of rapid growth or when vulnerabilities are limited. When such signals can be detected, the measures that can be taken are often not the interest rate adjustments, conventional monetary policy tool, but rather a range of regulatory measures that are far less commonly implemented, unconventional monetary policy tools. In addition, such measures are often not the sole responsibility of the central bank, depending on the country, the process of addressing these areas can involve a number of regulatory and oversight agencies. The result of all these factors is that developing policies to achieve and protect financial stability is a complex matter (Uslu and Kahveci, 2014; 75). Despite this challenge, alongside communication aimed at achieving price stability, communication for the purposes of financial stability has become a very important tool for central banks. In this regard, the number of financial stability reports (FSR), the main communication tool for financial stability, has expanded rapidly since 2000 and continued after the financial crisis (Uslu and Kahveci, 2014).

Another impact of central bank communication on the financial stability has been to decrease the asymmetric information and coordination problem by informing markets. Thus, FSRs play a crucial role here. A number of central banks that did not publish FSRs began to do so after the global crisis (e.g. Italy, Greece, China, India, Croatia and Jordan) (Vasko, 2012). While these reports provide useful information about the well-functioning parts of the sector to the public and to the financial markets, they also serve as a precautionary tool for economic decision makers and regulatory authorities (Knütter et al., 2011; p.13).

The Financial Stability Transparency Index developed by Vasko (2012) has been increasing since 2000. The increase accelerated in 2009 following the crisis (Figure

The study done by Born et al. in 2013 shows that financial reports are very important in terms of creating news in the sense that the views expressed in FSRs are reflected in the stock market and of reducing market volatility. By comparison, speeches and interviews on matters of financial stability had impact on market returns only at times of crisis, indicating the potential importance of this communication tool during periods of financial stress (Born et al., 2013).

Conventional and Unconventional Policies

It has been very challenging for central banks to manage monetary policy and to give direction to the economy by using conventional monetary policy tools after the global crisis of 2007-2009. Indeed, the global financial crisis has engendered very significant outcomes with major implications for monetary policy.

When we talk about the term conventional monetary policy, we refer the times where monetary policy mainly acts by setting a target for the overnight interest rate in the interbank money market and adjusting the supply of central bank money to that target through open market operations. In normal times, monetary policy transmission process should be working very well and the central bank, by steering the level of the key interest rates, effectively manages the liquidity conditions in money markets and pursues its objectives over the medium term. This has proved to be a reliable way of providing sufficient monetary stimulus to the economy during downturns, of containing inflationary pressures during upturns and of ensuring the sound functioning of money markets. During these normal times, it should not be necessary that the central bank is neither involved in direct lending to the private sector or the government, nor in outright purchases of government bonds, corporate debt or other types of debt instrument (Smaghi, 2009).

But, in abnormal times, conventional monetary policy tools may prove insufficient to achieve the central bank’s objective. One of the reasons might be the so powerful economic shock where the zero nominal interest rate should not be enough. Second reason might be the significantly impaired monetary policy transmission process. Whenever the transmission channel of monetary policy is severely impaired, conventional monetary policy actions are largely ineffective. Under these circumstances, cutting policy rates further is not possible, so something else is necessary like additional monetary stimulus (Smaghi, 2009).

Unconventional Policies

The post-crisis situation drove central banks to implement unconventional monetary policies to deal with the crisis and to minimize the damage to the economy. In this context, central banks have started to implement unconventional monetary policy measures and to practice quantitative easing and asset purchasing programs, where policy rates have been at or close to their zero effective lower bound, to provide more incentives to the economy and to contribute financial stability.

Quantitative Easing: Quantitative easing (QE) were used for the first time as a description of its policy by a central bank in the Bank of Japan's Japanese-language publications. In its announcement of 19 March 2001 – universally cited by commentators as the first time a policy called QE was implemented by central bank – the Bank of Japan announced a high target of bank reserves held with the central bank, which would (at least partly) be achieved by purchasing more government bonds (Bank of Japan, 2001; Lyonnet and Werner, 2012:96).

After the financial crises, major central banks pioneered by the FED started to carry out large-scale asset purchases of Treasury securities and other debt instruments in order to put further downward pressure on long-term interest rates, thereby stimulating consumer and business spending. In addition to this particular measure, known as QE, FED, lowering short-term interest rates essentially to the zero lower bound, has pioneered a new an unconventional measure by adding forward guidance to the policy mix.

Forward Guidance: Implementing unconventional monetary policies made it harder for the public to understand the future path of monetary policy, thus central banks have started to take new steps in communication policies that are very different from previous methods (Woodford, 2013, s.96).

Over time this has given way to the view that effective monetary policy is possible through transparency and effective communication and later to the idea that the management of expectations is fundamental to monetary policy. Effective communication is essential to expectation management. Now communication is accepted both in academic literature and in real-world practice as central to the effectiveness of monetary policy (Kahveci and Odabaş, 2016). In this regard, central banks’ communication policies and tools have become as important as unconventional policies, measures and tools. Forward guidance, which emerged as a discrete unconventional policy tool, started to play a key role in terms of central banking communication, come to the fore with the crisis and increasingly adopted and used by central banks related to their long term expectations and to their transparency (Vayid, 2013, s. 25). The post-crisis transition in Central Bank policy from mystery and inscrutability to the era of transparency and the importance of “forward guidance” is a demonstration of how rapidly and radically communication strategy has changed (Kahveci and Odabaş, 2016). Importantly, forward guidance is designed to contribute to monetary easing and to halt the decline in economic activity. With the policy rate practically at zero, and with some central banks using QE as an additional monetary stimulus, it became more difficult for markets and the public to anticipate how monetary policy would affect and respond to economic conditions (Vayid, 2013, s. 25).

Forward guidance is a communication tool which is conditional on the assessment of the economic outlook and gives direction to the future of monetary policy. Praet (2013) defines forward guidance as an advanced form of communication which is related to the future course of monetary policy. This type of orientation of central banks emerges as a form of tool especially when the monetary policy challenges arise in exceptional circumstances. Forward guidance is not necessarily a dimension of policy that becomes relevant only at the lower bound of policy rate, the experience of reaching the lower bound has undoubtedly increased the willingness of central banks to experiment forward guidance (Woodford, 2012, s.2).

As in every step of central banks communication, forward guidance is a monetary policy tool that would also be thought deeply and would be formatted and built carefully. The message that would like to be given should be supported by policy text and more importantly it should be dealt with holistic approach along with all other monetary policy tools instead of a single policy tool (Yilmaz & Kahveci, 2014).

In this regard, explicit conditional statements about the future path of the policy rate and of QE stimulus started to be used to guide markets that the central bank will keep rates at this level for longer (allowing inflation to be higher in the recovery) than consistent with its normal policy rule.

Negative Interest Rate:Aftermath of the global financial crisis, several central banks around the world have introduced negative interest rate policy as an unconventional policy to provide additional monetary stimulus. Danmarks Nationalbank (DN), the European Central Bank (ECB), Sveriges Riksbank and the Swiss National Bank (SNB) and most recently the Bank of Japan (BoJ) all cut their key policy rates to below zero over the period from mid-2014 to early 2015. The motivations behind the decisions either to counter a subdued inflation outlook or to focus on currency appreciation pressures in the context of bilateral pegs or floors on exchange rates.

Negative interest rates so far suggest that modestly negative policy rates are transmitted to money market rates in very much the same way as positive rates (Bech, and Malkhozov, 2016) are and have had a positive effect on the economy, helping to lower bank funding costs and boost asset prices. In addition, Jobst and Lin (2016) says, negative rates have significantly enhanced the signalling effect of the ECB’s monetary stance strengthening its forward guidance. However, questions remain as to whether negative policy rates are transmitted to the wider economy through lower lending rates for firms and households, especially in rates associated with bank intermediation (Bech, and Malkhozov, 2016).

Macro-prudential Regulations: Regulation of financial services has traditionally concentrated on so-called micro-prudential regulation, which is geared towards controlling excessive risk-taking in individual banks. However, micro-prudential regulation does not always secure the robustness of the financial system as a whole. The recent crisis is a reminder in that regard. In the aftermath of the financial crisis of 2007-2009, a macro-prudential approach to financial regulation has emerged. Macro-prudential regulation is concerned with the risks at the level of the financial system (systemic risk ) and recognizes the importance of general equilibrium effects, that is how the financial sector interacts with he real economy (Borchgrevink et al. 2014).

Da Silva et al. (2012) define macro-prudential measures as to calibrate existing micro-prudential rules and/or to extend them to cover exhaustively all dimensions of vulnerabilities in a financial system in order to put systemic risk below an agreed upon threshold (Da Silva et al., 2012).

IMF (2011) survey suggests that it may be appropriate for several countries, based on their current circumstances, to consider prudential measures or capital controls in response to capital inflows (IMF, 2011).

Mishra, et al. (2014) said that macro-prudential policy is important in minimizing the spillover effect of US monetary policy. Their results suggest that countries with deeper financial markets, better macroeconomic fundamentals, and better macro-prudential policy experienced less exchange rate depreciations and less increase in government bond yields (Mishra, et al. 2014).

Research Method

In this study, a number of central banks from developed and developing countries have been chosen and analyzed in terms of their monetary policy changes and especially their communication strategies. In this regard, by consulting the opinions of experts from the Central Bank of Turkey, the Federal Reserve (Fed), European Central Bank (ECB), the Bank of England, the reserve bank of and Australia and New Zealand and central bank of Japan, Canada, Norway and Sweden have been chosen as central banks from developed economies and the central banks of Brazil, South Africa, Russia, China, Poland, India, Mexico and Turkey have been chosen as developing country central banks. The research is based on a literature review and a holistic, multiple method case studies, drawing on websites, a primary communication tool for central banks, and on the basic reports on their websites. We also benefit from the survey commentaries of the BIS conducted in 2013. The aim of this paper is to analyze the main monetary policy shifts of central banks before and after the crisis and to see their impacts on monetary policy and communication strategies.

Findings

Common Policy for Developed and Developing Countries: Financial Stability

After the global financial crises, significant precautionary measures began to be taken to cope with the increasing systemic risks to the financial system. Additionally, in place of the micro approach that focused on each financial institution individually, a macro approach that sees the financial system as more than just the sum of the parts and evaluates it as a whole has been accepted. One of the factors that has been noticed in both developing and developed countries, while there has been no major change in monetary policy roles, yet there has been a significant increase in the roles central banks play in financial stability (Table

Unconventional Monetary Policies During and After the Crises

The most fundamental point after the crisis is that there is a sharp difference between the developed and the developing countries’ monetary policy choices and applications. Central banks in developed countries had only one main challenge to deal with: to minimize the negative impact of crisis on the economy and to return the economy to pre-crisis levels. To do that, they changed monetary policy strategies and started to use unconventional policies such as quantitative easing, negative interest rate policy and forward guidance. On the other hand, central banks in developing countries had to deal with at least two main challenges: to minimize the negative impact of crisis on the economy and return to pre-crisis levels, and additionally to deal with the negative effects of the unconventional monetary policies coming from developed economies. They not only had to cope with the crisis but also had to find solutions to challenges from developed countries such as increasing volatility of funds and increasing risks to the financial stability. To achieve that goal, they mostly started to implement macro-prudential measures. In this regard, it can be said that central banks in developing countries partially lost their independence in terms of selecting and applying policy choices and they became very dependent on the policies of developed countries’ monetary policy choices.

What is common in developing and developed countries in terms of policy mix during and after the global crisis is that they increased the awareness of financial stability and established new financial stability bodies and included financial stability in their policy mix. To do this some of them have changed their law and even their organizational structure.

Developed Countries’ Central Bank Policy Implementations

Prior to the crisis, the monetary policy conducted by central banks in advanced economies was predictable and the key policy tool was a short-term interest rate. Its transmission mechanism was reasonably well understood. However, due to the severity of the crises and the challenge of slow recovery, the central banks of major advanced economies (United States, United Kingdom, Japan, and euro area) have implemented a variety of unconventional policies since the beginning of the financial crises to restore the functioning of financial markets and intermediation.

The U.S. Federal Reserve (Fed) has been the leader in these efforts. Fed, having two legislated goals—price stability and full employment in the United States, widened its liquidity facilities significantly and reduced its policy interest rate to near zero. It has also provided forward guidance on the federal funds rate. This policy seeks to influence market expectations for the future path of short-term rates and so reduce long-term real interest rates. Fed also began purchasing financial assets (Treasury bonds and mortgage-backed securities) from the market, in successive programs referred to as QE.

The Bank of England (BoE) has also engaged in implementing unconventional monetary policies to loosen monetary conditions. These measures include increased liquidity support, actions to deal with dysfunctional financial markets and large-scale asset purchases. BoE has also recently introduced explicit forward guidance for its policy rate.

The European Central Bank (ECB) has adopted similar policies to promote recovery and price stability. The ECB has significantly extended the liquidity facility by offering longer term refinancing operations and purchased securities in troubled markets. The ECB recently adopted open-ended qualitative forward guidance on policy interest rates and stated its intention to keep interest rates at prevailing or lower levels “for an extended period of time”.

Following the financial crises The Bank of Japan (BoJ) adopted a number of unconventional measures to promote financial stability. BoJ increased the pace of its Japanese Government bonds purchases. In order to response to the deflation and slowing recovery, BoJ introduced Comprehensive Monetary Easing Policy. Unlike the Federal Reserve, the BOJ has had no forward guidance related to a policy interest rate. The BOJ applies forward guidance to indicate its future stance over the continuation of quantitative and qualitative monetary easing (QQE).

Due to the severity of the crises and the challenge of slow recovery, to cope with the weak demand and the low inflation, six developed economies’ central banks, except from Australia, New Zeland and Norway, has carried out a QE program and Swiss National Bank, Bank of Japan and ECB have announced the introduction of negative interest policy (Table

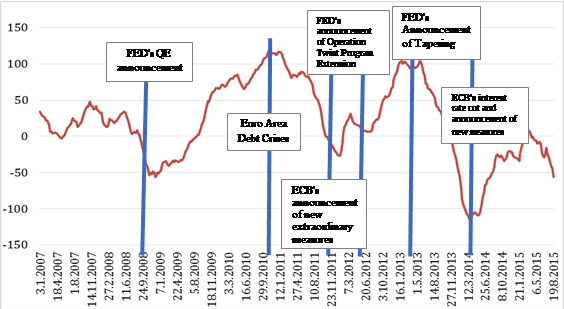

FED was the first with its November 2008 announcement and Bank of England was second in 2009 which started to carry out QE program. Then ECB started to give liquidity to the market with its credit easing and asset purchase program. In a dramatic change of policy, on 22 January 2015 ECB announced an expanded asset purchase programme after FED’s purchases were halted on 29 October 2014 after accumulating $4,5 trillion in assets. Asset purchase programs implemented by FED and ECB are the most affecting the market and shaping capital flows to developing countries. Although Bank of England’s and other central banks’ programs have been effective, their impact on global markets and on developing countries have been more limited (Figure

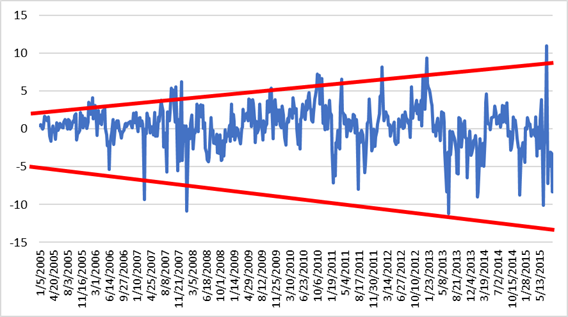

A large amount of capital flows to developing countries by the announcements of QE programs after the global crises continued until the announcement of ending QE program by the FED in 2014. Then, significant capital outflows have been observed until ECB's asset purchase announcement. Then, it has been volatile with normalisation talks (Figure

After analyzing the measures taken in detail after the crises, it is very remarkable that it is neither the start of the implementation nor the end of the asset purchase program that has impact on the markets, rather its communication to the market which means forward guidance measures which was implemented (Figure

The Bank of Canada (BoC) was the first major central bank to use forward guidance in April 2009, indicating that the Bank intended to keep the policy rate at the effective lower bound until the end of the second quarter of 2010, explicitly conditional on the outlook for inflation. Vayid (2013) says the BoC’s conditional commitment succeeded in changing market expectations of the path of the policy rate, lowering longer-term interest rates, and thus underpinning a rebound in growth and inflation which, in turn, obviated the need to use other unconventional policies, notably QE. Carney (2013) reasons that the commitment worked because it was exceptional, explicit and anchored in a highly credible inflation-targeting framework. It was also backed by the availability of exceptional liquidity; and it reached beyond central bank watchers to make a clear, simple statement directly to Canadians (Vayid, 2013, s. 28).

Developed economies’ Central banks (except for Australia, Switzerland and Japan), analyzed in this research, put forward guidance into practice (Table

Developing Countries’ Central Bank Policy Implementations

During the period after the global crises, starting from developed economies and had impact on all over the world, the main shared point among the developing economies’ central banks, except for South African Reserve Bank, is to deal with the negative effects of the unconventional monetary policies in developed economies; such as increasing volatility of funds (Figure

There is very interesting point to mention which none of the developing economies’ central banks deployed neither QE, nor forward guidance nor negative interest rate policy as the case for developed economies (Table

One of these examples, in 2008 PBoC started to use differentiated required reserves. First it started as increased required reserves for the bigger banks in size, changed into case-by-case differentiation in order to control the money, credit and liquidity growth conditions in 2011. Thus the different reserves requirements ratios were applied to the banks in terms of their size. PBoC used macro-prudential measures both before and after the crises. Before and during the crises Windows guidance continued to use to guide the banks. In 2009, PBoC give some guidance about the increasing credit support to basic sectors and credit controls of companies with higher consumer of energy.

Turkey is another country put new framework into practice after the global crises. The CBRT has introduced a new monetary policy framework as of late 2010, through modifying the inflation targeting regime it has been implementing since 2006. Therefore, the CBRT diversified its instruments and started using the interest rate corridor, liquidity management and reserve options. Hence, the documents released after the MPC Meeting is tripled, covering decisions on three instruments. Unique macro-prudential policy called Reserve Option Mechanism (ROM) designed by CBRT is mainly an “automatic stabilizer” (in a way that banks can internally adjust the utilization rates of reserve option against external shocks). The ROM enables the banks to keep a certain ratio of TL reserve requirements in FX and gold. The coefficients showing the amount of FX or gold to be held per unit of TL reserve requirements are defined as the Reserve Option Coefficients (ROC). Since the changes in the facility provided by the ROM as well as those in the ROC influence the ratio of TL reserves held in FX, this policy directly affects the TL and FX liquidity management. As this concept enables each bank to make its own optimization given its own constraints, the ROM is considered to be more efficient in an economic sense compared to other instruments used in FX liquidity management. Moreover, parameters of the system can also be used as a cyclical instrument to adapt to permanent changes in domestic and external environment when necessary (CBRT, 2014). There is also another measure taken by CBRT in terms of leverage ratios. According to this measure, the banks that raise the leverage ratios to excessive levels compared to the current circumstances might be subjected to additional reserve requirement. In this context, a countercyclical and macro-prudential policy is based on leverage. The idea behind this is that operating of the financial system under a high leverage would cause economic damage in the medium and long term. By posing higher reserve requirements for those banks which have higher leverage should keep the banks using additional leverage. Another measure taken by CBRT is maturity based reserve requirement. The maturity based RR has been designed to reduce maturity mismatches between assets and liabilities of banking sector. Leverage ratios, which will be effective in 2018 as per the timetable of the Basel III, are projected to impose an additional RR on the banks with low leverage ratios to contribute to financial stability by preventing a sharp fall in leverage ratios prior to this period and by limiting bank indebtedness.

Both before and after the crisis / India’s experience with the conduct of macro-prudential policy has spanned initiatives to address both dimensions of systemic risks, pro-cyclicality and crosssectional risks. India, has been using macro-prudential measures for systemic risks for years, has continued its macro-prudential measures after the global crises. The measures taken for the sectors (e.g. real estate) growing disproportionately before the global crises have eased after the second half of 2008 and Reserve Bank of India has decreased the provision ratios and risk weigh for standard assets.

Conclusion and Discussions

The negative effects of global financial crises on the countries are wide and different so it has been very challenging to cope with it. During this crisis era, central banks in developed countries had only one challenge to deal with: to minimize the negative impacts of crisis on the economy and to get return the economy back to pre-crisis levels. To do that, they changed monetary policy strategies and started to use unconventional policies such as quantitative easing, negative interest rate policy and forward guidance. The unconventional monetary policy measures of developed countries had a certain impact on the emerging market countries. Especially the quantitative easing policies have created abundant and excessively volatile global liquidity conditions. Short-term and greatly volatile capital flows to emerging markets resulted in increasing uncertainty and risk. These developments required the policy makers of emerging economies to set new flexible policies. On the other hand, central banks in developing countries had to deal with at least two challenges: to minimize the negative impact of crisis on the economy and return to pre-crisis levels, and additionally to deal with the negative effects of the unconventional monetary policies in developed economies. They not only had to cope with the crisis but also had to find solutions to challenges coming from developed countries such as increasing volatility of funds and increasing risks to the financial stability, due to quantitative easing, negative interest rate and forward guidance policies. To achieve that goal, they mostly started to implement macro-prudential measures. In this regard, it can be said that central banks in developing countries partially lost their independence in terms of selecting and applying policy choices and they became very dependent on the policies of developed countries’ monetary policy choices.

What is common in developing and developed countries during and after the global crisis is that they increased the awareness of financial stability and established new financial stability bodies and included financial stability in their policy mix. To do this, some of them has changed their law and even their organizational structure.

It can be said that global efforts are needed to cope with this kind of global financial crises since this time of globalization one measure taken by one country, regardless of the effects on other countries, can deepen the crises instead of providing the solution. Since the crisis is global, its solutions must be decided globally. In this regard G-20 countries leaders, economy ministers and central bank governors get together time to time to discuss the situation and to find the best solutions. Again it is never enough, because after more than eight years the financial global crises started, today we are still living in the crises era and we did not totally recover from the crises and we are still talking about the measures that can be taken in terms of monetary policy strategies which may be followed. Apparently, in this regard we still have a long way to go. Further surveys can be focused on how to find solutions to the global crises together both developed and developing countries without having negative effects on each other.

References

- BIS. (2013). Survey on Monetary Policy Communications After the Crisis: What has changed and why?

- Bank of Japan (2001). New Procedures for Money Market Operations and Monetary Easing, March 19, 2001, Bank of Japan http://www.boj.or.jp/en/announcements/release_2001/k010319a.htm/

- Bech, Morten., and Malkhozov, Aytek. (2016). How have central banks implemented negative policy rates? BIS Quarterly Review, March 2016

- Borchgrevink, H, S Ellingsrud, and F Hansen (2014). Macroprudential Regulation – What, Why and How, Norges Bank: Staff Memo, 13, 1–15.

- Born, B., Ehrmann, M., & Fratzscher, M. (2013). Central Bank Communication on Financial Stability. TheEconomic Journal, 124, 701–734 (June).

- Carney, M. (2013). Monetary Policy After the Fall. Eric J. Hanson Memorial Lecture, University of Alberta, Alberta (May).

- CBRT (2014). Monetary and Exchange Rate Policy For 2014, http://www.tcmb.gov.tr/wps/wcm/connect/a136abf9-b3db-49cd-a819-d4d4cea13ce7/monetary_2014.pdf?MOD=AJPERES&CACHEID=ROOTWORKSPACEa136abf9-b3db-49cd-a819-d4d4cea13ce7

- da Silva, L. A. P., Sales, A. S., & Gaglianone, W. P. (2012). Financial Stability in Brazil. Central Bank of Brazil, Research Department Working Papers Series, (289).

- Jobst, Andreas., and Lin, Huidan. (2016). Negative Interest Rate Policy (NIRP): Implications for Monetary Transmission and Bank Profitability in the Euro Area, IMF working paper wp16172.

- IMF (2011). Recent experiences in managing capital inflows – cross-cutting themes and possible policy framework. Retrieved May 24, 2017, from http://www.imf.org/external/np/pp/eng/2011/021411a.pdf.

- Kahveci, E., Odabaş, A., (2016) Central banks’ communication strategy and content analysis of monetary policy statements: The case of Fed, ECB and CBRT Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 235, 618-629.

- Kahveci, E., & Sayilgan, G. (2006). Globalization of financial markets and its effects on central banks and monetary policy strategies: Canada, New Zealand and UK case with inflation targeting. International Research Journal of Finance and Economics, 1, 86-101.

- Knütter, R., Mohr, B. & Wagner, H. (2011). The Effects of Central Bank Communication on Financial Stability: A Systematization of the Empirical Evidence. Discussion Paper No. 463, University of Hagen.

- Lyonnet, V., & Werner, R. (2012). Lessons from the Bank of England on ‘quantitative easing’and other ‘unconventional’monetary policies. International Review of Financial Analysis, 25, 94-105.

- Mishra, P., Montiel, P., Pedroni, P., & Spilimbergo, A. (2014). Monetary policy and bank lending rates in low-income countries: Heterogeneous panel estimates. Journal of Development Economics, 111, 117-131.

- Praet, P. (2013). Forward Guidance and the ECB, VoxEU.org column published on 6 August 2013. Available at http://voxeu.org/article/forward-guidance-and-ecb

- Siklos, P. L. (2014). Communications Challenges for Multi‐Tasking Central Banks: Evidence, Implications. International Finance, 17-1, 77–98.

- Smaghi, Lorenzo Bini. (2009). Conventional and unconventional monetary policy. https://www.ecb.europa.eu/press/key/date/2009/html/sp090428.en.html (Reached: 30 September 2016)

- Vasko, D. (2012). Central Bank Transparency and Financial Stability: Measurement, Determinants and Effects. Master Thesis, Charles University, Prague.

- Vayid, I. (2013). Central Bank Communications Before, During and After the Crisis: From Open Market Operations to Open-Mouth Policy. Bank of K Working Paper No.2013-41.

- Woodford, M. (2012). Methods of Policy Accommodation at the Interest-Rate Lower Bound. In Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City Economic Symposium on The Changing Policy Landscape, Jackson Hole, WY.

- Woodford, M. (2013). Forward Guidance by Inflation-Targeting Central Banks. Sveriges Riskbank Economic Review, 2013(3) Special Issue, 81-120.

- Yılmaz, C. B. & Kahveci, E. (2014). Merkez Bankası İletişiminde Yeni Bir Araç: Sözle Yönlendirme (Forward Guidance), Ülke Örnekleri ve Türkiye Uygulamaları. Bankacılar Dergisi, 88, 5-26.

- Uslu, Emrah and Kahveci, Eyup (2014). Assessing the value of financial stability reports Content, Priorities and Popularity, Central Banking, 25 (4) 75-86.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

20 December 2017

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-033-4

Publisher

Future Academy

Volume

34

Print ISBN (optional)

--

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-442

Subjects

Business, business studies, innovation

Cite this article as:

Kahveci, E. (2017). How Monetary Policy Strategies Changed After the Global Financial Crises?. In M. Özşahin (Ed.), Strategic Management of Corporate Sustainability, Social Responsibility and Innovativeness, vol 34. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 396-412). Future Academy. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2017.12.02.34