Abstract

This paper discusses school desk graffiti as an example of conformity/non-conformity towards main education values of schools. So, from four different school categories (vocational high school; science high school; Anatolian high school; Islamic divinity high school) and five different high schools, 3092 photographs had been taken to collect graffiti samples. These samples are categorized under two clusters; conformity and non-conformity to the 20 categorizations (educational values of schools). These educational values of school organizations derived from the Ministry of National Education’s report, which aimed to draw the “The Profile of 21st Century Student”. According to results, main findings of this research can be grouped under three points: (1) Organization characteristics affect the content of the graffiti. (2) School graffiti is an example of conformity to the organizational values. (3) School graffiti is an example of non-conformity to the organizational values. By means of these findings, graffiti as overlooked form of communication provide a discussion ground to look at the interaction between agent (student) and organization (school).

Keywords: GraffitiConformityNon-ConformityOrganizational ValueEducation

Introduction

Aim of this paper is to discuss school desk graffiti as an example of conformity/non-conformity towards main education values of schools. In this manner research question is whether graffiti be an example of conformity or non-conformity towards educational values of schools?

To explain in detail, this research discusses that whether writings, symbols or drawings on the desks in high school classrooms, which students draw, can be an example of conformity or non-conformity toward organizational values. For this purpose, graffiti samples had collected by photographs. So from four different school categories (vocational high school; science high school; Anatolian high school; Islamic divinity high school) and five different high schools, 3092 photographs had been taken. Afterwards, these photographs analyzed under the light of a question: whether they can be an example of conformity or non-conformity toward organizational values. To define organizational values, Ministry of National Education’s report had been used. The title of this report is “The Characteristics of 21st Century Student”. Within the frame of this report a research had been conducted to determine educational values that corresponds to the desire of 21st century students of secondary education. So it was an “formal” rationale to understand and determine macro level educational values of secondary education. According to these values, categories are defined. Under these categories 3092 photographs had been analyzed.

Later in paragraphs of this paper, firstly theoretical framework which research motivation points out can be found. Afterward, research method and findings will be shared. Finally, with conclusion and limitations titles discussion of this paper will reach to the end.

Theoretical Framework

School, a Hot Topic in Social Science

School institution, -for its emergence it was believed that this institution would activate meritocracy by enfranchising abilities instead of hereditary privileges (Bourdieu, 2006: 39)- have been discussed under different categories such as a panoptic discipline institution (Foucault, 1991); at the frame managing and controlling, as a gardener for Bauman (2001: 145); and for Bourdieu (2006: 36) as an institution which re-produce existent borders been established at frame of economic and cultural capital. Similarly, According to Cohen (1965) school, through teachers and managers imposes expectations based on social- middle class- standards on students. Of course the main expected output for this imposition process is to create conformity toward macro level values and norms of the society. As can be seen, under the title of school and education, a long history of discussion can be found. But for this study, school concept had been taken as an organization type, which has its unique position in construction of control in the society. In this regard it is a “value-transferor organization” to the young generations of the society. Students are also taken as members of the school organization -not consumers or customers (For further reading please see (Eagle & Brennan, 2007; Schwartzman, 1995). ) -. So for the young generations of the society there are two options: to conform or not to conform to these values.

Conformity literature has a long history in social science (Milgram, 1964; Asch, 1956; Sherif, 1961; Schachter, 1951). By means of this mainstream literature and following studies, conformity of organizational values is a well-discussed and defined field of study. At this point resistance literature also provides a different ground to our discussion (Jenkins, 1998; Jermier, Knights, and Nord, 1994; Lawrence, & Robinson, 2007; Mumby, 2005). Without losing focus point of this paper, resistance will be discussed briefly. At the frame of Foucaldian perspective, resistance examples –creating alternative identities, and reversing discourse (Alakavuklar, 2012, s. 43)- are theoretical grounds to discuss agent’s reaction towards values. With resistance examples, it is possible to read non-conforming motivations of agents to the organizational values. For this study, student graffiti on high school desk had been taken as “possible” examples of conformity and resistance (non-conformity) toward school based organizational values.

Graffiti in the Intersection of Agent-Organization

Gach (1973: 285) defines graffiti in 70’s as an “overlooked form of communication”. In some ways it is also still an overlooked concept in different fields of social science. Graffiti are statements and drawings, which penned, penciled, painted, crayoned, lips ticked, or starched on desks or walls (Gach, 1973: 285) etc. As Farnia (2014: 48) quoted, according to Blume (1987: 137), “[graffiti is any] pictorial or written inscription for which no official provision is made and which is largely unwanted, and which are written on the most various publicly accessible surfaces, normally by anonymous individuals”.

Halsey and Young (2006: 279) depicted commonplace assumptions toward graffiti as “the writer’ s supposed boredom, or the writer’ s desire to damage and deface, or the writer’ s lack of respect for others’ property”. These assumptions also mainly shape attitudes of formal organizations –like school- toward graffiti. Although school’s approaches are in the same direction with these “common place assumptions”; graffiti are accepted as inevitable or maybe normal in classrooms.

According to Ferrell, (1995: 34) “in a remarkable variety of world settings, kids (and others) employ particular forms of graffiti as a means of resisting particular constellations of legal, political, and religious authority.” Graffiti are also communication tool for political groups (Pietrosanti, 2010); and tool to challenge the authority (Farnia, 2014); and expression which transforms the political meaning of Berlin Wall (from Ferrell, 1995: 34; Waldenburg, 1990); and -As Ferrell (1995: 37) quoted from his interviews- a way “means (to say) I’m here” when facing with organizations.

As Taylor (2012) assumed that “peer emulation, aggression, identity formation, may lead mid-late adolescents (15–17 years old) to be involved in graffiti writing. In this regard, this study also focuses on mid-late adolescents graffiti expressions within the context of school. Context of school also attracts attentions of graffiti researchers. As Farnia (2014: 50) quoted “Kan (2006) investigated graffiti writing by students in secondary schools in Kenya; … and results indicated that graffiti was used as a medium to communicate opinions on different topics like love and sex, school authority, student welfare, religion and politics.” Şad and Kutlu (2009) also conduct a research on school graffiti. According to their content analysis results graffiti are clustered under two titles; socially acceptable topics and anonymous inscriptions. According to the results socially acceptable topics are belongingness, homesickness, romance, and humor or the form of someone’s name and signs (doodling); and anonymous inscriptions are sex and politics or religion. In the light of these studies, this paper positions its research motivation to read graffiti as a communication of agents with organizations. In this way of communication, -between agent and organization via graffiti- content is going to be focused just on organizational values.

Methodology

This is an exploratory study. In this study, qualitative and quantitative techniques are used. As mentioned before graffiti samples had collected by photographs. Related literature to use photographs in social science research had been followed (Knoblauch et.al., 2008; Bohnsack, 2008; Christmann, 2008). From four different school categories (vocational high school; science high school; Anatolian high school; Islamic divinity high school) and five different high schools, 3092 photographs had been taken.

To analyze photographs, firstly categorizations are determined. Categorizations consist of educational values of schools. To determine categorizations, Ministry of National Education’s report -“The Characteristics of 21st Century Student”- had been used. In this regard 20 categorizations were determined. These categories are:

Become RichBecome a Honest person

Become IndependentDeeply Attached to the Cultural Values

Having a good JobBecome an ethical Person

Become FamousBecome a Fair Person

Become a Respectable PersonBecoming a wise Person

Become a Responsible PersonBecome a Hardworking person

Become HelpfulBecome an Authentic and Productive

Become Honorable PersonBecome a socially sensitive person

Become Spiritual PersonRespectful for diversity

Being Helpful for Family and RelativesBecome a obedient person

Under every category, two clusters created: conformity and non-conformity. By means of this categories and clusters, 3092 photographs were analyzed.

Findings

After analysis of photographs, under 12 categories, (educational values); 409 conformity and non-conformity examples were determined. In this regard, there were 70 conformity and 339 non-conformity examples. By means of Table

As can be seen when table analyzed, “Become Spiritual Person” (Conformity: 19 – Non-Conformity: 83); “Become an ethical Person” (Conformity: 0 – Non-Conformity: 83); “Become a Hardworking Person” (Conformity: 23 – Non-Conformity: 78) are prominent value examples which graffiti can be linked to.

One another interesting finding of these result is graffiti is not just about desire to damage and deface, or the writer’ s lack of respect for others’ property (Halsey and Young, 2006: 279) and it is not just about non-conformity. Graffiti is also related with conformity toward some values like spirituality. Some examples from the conformity to the value of “Become Spiritual Person” are shared at below:

Vocational high School – IMG2639:

Anatolian high School – IMG1365: “

As a result graffiti has potential to be both examples of the conformity and non-conformity towards organizational values. At this point, by means of these results, two possible assumptions are shared at below:

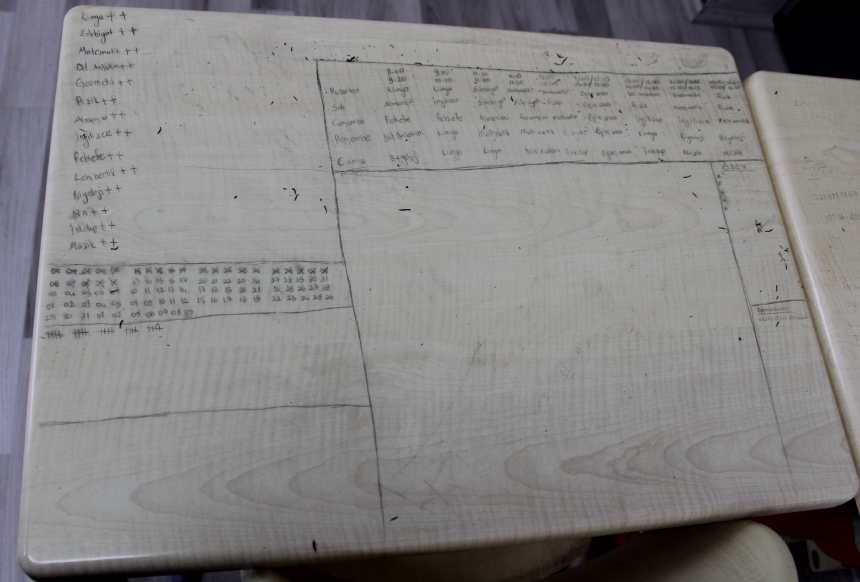

The value of “Become a Hardworking Person” is also be linked to the 23 conformity examples. One of these graffiti, in the Science High School, student used his/her desk as a calendar includes time and dates of every courses and also a kind of performance evaluation technique. This figure is also shared at below:

One another interesting result is number of high school’s conformity and non-conformity examples vary according to academic performance. When we look at conformity numbers to the value of “Become a Hardworking Person” leading high school category is science (17 conformity graffiti). On the other hand Anatolian High School has 3 examples of conformity graffiti and; Vocational High School has also 3 examples of conformity. In this regard academic performance can also affect the content of graffiti. Besides it is necessary to see the role of the type of the high school. Because when wee look at numbers of conformity and non-conformity to the organizational values; we see just 9 graffiti examples are related to the 5 different values. But 30 graffiti examples are related to the one value, which is “Become a Hardworking Person”. Because in science high schools success rates to pass university admission test is so high. So conformity to the organizational values, and avoiding from non-conformity is also related with characteristics of the organization. In this regard agent (student) and organization interact with each other. And this interaction creates its unique experiences within in the minds of agents (students). So another assumption example is shared at below:

Conclusion

As mentioned before, this is an exploratory research. And this paper is also first step to discuss graffiti within a specific organizational context. So by means of these findings it is possible to answer as “yes”, to the research question of this paper (whether graffiti be an example of conformity or non-conformity towards educational values of schools?). In this regard this paper also offers 3 assumptions. To test these assumptions, further discussions and researches are needed.

Limitations

Conformity and non-conformity examples were determined by author’s analyses. So further analyses like sending data to reviewers and to check inter-rater reliability are needed.

References

- Alakavuklar, O., N., (2012). Yönetsel Kontrole Direncin Ahlakı, Yayınlanmamış Doktora Tezi, Dokuz Eylül Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü, İzmir.

- Asch, S. E. (1956). Studies of independence and conformity: I. A minority of one against a unanimous majority. Psychological monographs: General and applied, 70(9), 1.

- Bauman, Z. (2001), Parçalanmış Hayatlar, (Çev. İsmail Türkmen), Ayrıntı, İstanbul.

- Blume, R. (1985). Graffiti. In T. A. van Dijk (Ed.), Discourse and literature: new approaches to the analysis of literary genres (Vol. 3, pp. 137–148): John Benjamins Publishing.

- Bohnsack, Ralf (2008). The Interpretation of Pictures and the Documentary Method. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 9(3), Art. 26, http://nbnresolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0114-fqs0803267.

- Bourdieu, P., (2006). Pratik Nedenler: Eylem Kuramı Üzerine. (Çev. Tanrıöver, H. U.), Hil Yayın, İstanbul.

- Christmann, Gabriela B. (2008). The Power of Photographs of Buildings in the Dresden Urban Discourse. Towards a Visual Discourse Analysis. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 9(3), Art. 11, http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0114-fqs0803115.

- Cohen, A. K., (1965). "The Sociology of the Deviant Act: Anomie Theory and Beyond", American Sociological Review, 1965, p. 5-14.

- Eagle, L., & Brennan, R. (2007). Are students customers? TQM and marketing perspectives. Quality assurance in education, 15(1), 44-60.

- Farnia, M. (2014). A Thematic Analysis of Graffiti on the University Classroom Walls-A Case of Iran. International Journal of Applied Linguistics and English Literature, 3(3), 48-57.

- Ferrell, J. (1995), “Urban graffiti: Crime, control, and resistance,” in Youth and Society, 27, pp. 73–92.

- Foucault, M. (1991) Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison. London: Penguin Books.

- Jenkins, R. (1998). From Criminology to Anthropology? Identity, morality, and normality in the social construction of deviance. (ed.) Holdaway, S., and Rock, P.,Thinking About Criminology, 133-160.

- Jermier, J. M., Knights, D. ve Nord, W. R. (1994) Resistance and Power in Organizations. London: Routledge.

- Gach, V. (1973). Graffiti. College English, 35(3), 285-287. doi:

- Halsey, M., & Young, A. (2006). ‘Our desires are ungovernable’ Writing graffiti in urban space. Theoretical criminology, 10(3), 275-306.

- Kan, J. A. W. (2006). A sociolinguistic analysis of graffiti in secondary schools: a case study of selected schools in Nyandarua. Unpublished master thesis, Egerton University, Nakuru, Kenya

- Knoblauch, H, Baer, A, Laurier, E, Petschke, S & B, S (2008). 'Visual Analysis. New Developments in the Interpretative Analysis of Video and Photography' Forum: Qualitative Social Research, vol 9, no. 3, 14.

- Lawrence, T. B., & Robinson, S. L. (2007). Ain't misbehavin: Workplace deviance as organizational resistance. Journal of Management, 33(3), 378-394.

- Milgram, S. (1964). Group pressure and action against a person. The Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 69(2), 137.

- Mumby, D. K. (2005). Theorizing resistance in organization studies A dialectical approach. Management communication quarterly, 19(1), 19-44.

- Pietrosanti, S. (2010). Behind the tag: A journey with the graffiti writers of European walls. Amsterdam: University of Amsterdam.

- Şad, S. N., & Kutlu, M. (2009). A study of graffiti in teacher education. Egitim Arastirmalari-Eurasian Journal of Educational Research, 36, 39-56.

- Schachter, S. (1951). Deviation, rejection, and communication. The Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 46(2), 190.

- Sherif, Muzafer (1961), Conformity-Deviation, Norms and Group Relation, (pp. 159-198). In Berg, Irwin A. (Ed); Bass, Bernard M. (Ed). Conformity and deviation, New York, NY, US: Harper and Brothers, viii, 449 pp.

- Schwartzman, R. (1995). Are students customers? The metaphoric mismatch between management and education. Education, 116(2), 215.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

20 December 2017

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-033-4

Publisher

Future Academy

Volume

34

Print ISBN (optional)

--

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-442

Subjects

Business, business studies, innovation

Cite this article as:

Ünlü, O. (2017). Graffiti As An Example Of Conformity/Non-Conformity Toward Organizational Values. In M. Özşahin (Ed.), Strategic Management of Corporate Sustainability, Social Responsibility and Innovativeness, vol 34. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 244-251). Future Academy. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2017.12.02.21