Abstract

As perceived organizational support (POS) has been found to have a strong impact on some important organizational outcomes such as performance, organizational commitment, and job satisfaction, a bundle of research has recently been tried to shed light on discovering the antecedents of POS. Thus, this study attempts to identify the effect of formalization, as one of the important dimension of organizational structure, on POS by evaluating the moderating role of trust in organization. The survey of this study is conducted on 343 administrative support staff, who works for airline industry. In order to understand the moderating effect of trust between formalization and POS, hierarchical moderated regression analysis has been employed. The results reveal that formalization positively and significantly affects perceived organizational support, while trust in organization moderates this relationship. More specifically, this relationship will be stronger when trust in organization is high. In other words, the relationship between formalization and POS will be weaker when trust in organization is low. Furthermore, the results are discussed and some suggestions for future research are proposed.

Keywords: Formalizationtrust in organizationperceived organizational supportmoderation

Introduction

Increasing the employee’s perception of organizational support is very vital for managers in order to reach their organizational goals by executing their formulated strategies. According to organizational support theory, employees form general beliefs about how much their organization values their contributions and cares about their well-being (Eisenberger et al., 2001; Eisenberger et al., 1997; Eisenberger et al., 1986). Based on the norm of reciprocity (e.g. Blau, 1964; Gouldner, 1960), this perceived organizational support (POS) may stimulate employees to care more about the organization’s welfare and to provide greater effort in order to reach organizational goals and objectives (Eisenberger et al., 2001). Therefore, managers should find ways in order to increase the employee’s perception of organizational support.

By using the lens of organizational support theory (Eisenberger et al., 1986); formalization, which is one important dimension of organization structure (e.g. Pugh et al., 1968), may be an effective instrument as a strategy implementation towards increasing POS. In other words, formalization can provide a channel for social exchange process between employee and employer in organizations. As few studies have examined the relationship between organizational structure and POS (e.g. Ambrose and Schminke, 2003) in related research stream; it is, therefore, important to investigate whether such relationship occurs especially among airline workers, where they commonly work for formalized structures. Further, Despite the main effects of formalization on POS, we have also raised questions about the intervening variables (e.g. trust) in this relationship.

Therefore, the aim of this study is twofold. First, we will examine the relationship between formalization and POS among administrative support staff, who works for airline industry. Second, we will investigate the moderating role of trust in organization for the relationship between formalization and POS.

Literature Review and Theoretical Framework

Perceived organizational support is a signal of an organization’s approval of employees’ contributions and care for their wellbeing in organizations (Rhoades and Eisenberger, 2002; Eisenberger et al., 1986). POS may increase felt obligation and also strengthen employees’ beliefs about their organization pays attention to increased performance (Rhoades and Eisenberger, 2002; Eisenberger et al., 2001). Therefore, POS may be linked to favorable outcomes in organizations such as job satisfaction (e.g. Rhoades and Eisenberger, 2002), commitment (e.g. Kim et al., 2016; Eisenberger et al., 2001; Armeli et al., 1998; Eisenberger et al., 1986), work engagement (e.g., Kinnunen et al., 2008), organizational identification (e.g. Lam et al., 2016), performance (e.g. Shen et al., 2014), withdrawal behavior (e.g. Aquino & Griffeth, 1999), and eco-initiatives (Paillé and Raineri, 2015). Kim, Eisenberger, and Baik (2016) reports that perceived organizational competence strengthened the relationship between POS and affective organizational commitment. They state that highly competent organizations can be more effective in preventing stressful situations such as role conflict and work overload. Also, they mention that leader consideration contributed more to POS than to perceived organizational competence, while leader initiating structure is more positively related to perceived organizational competence than to POS.

Consistent with social exchange theorists (e.g. Blau, 1964), an organization’s voluntary actions contribute more to POS (Rhoades and Eisenberger, 2002). Therefore, some favorable treatments such as supervisor support, autonomy, recognition, pay, promotion, the fairness of company policies, and job security received from the organization may provide the development of POS (Rhoades and Eisenberger, 2002).

Another important factor, which may contribute to the development of POS, is organization structure, that is an important part of organization’s strategy execution in strategic management process. Porter and Lawler (1965) defined organization structure as positions and parts of an organization and their systematically and relatively enduring relationships to each other. Dalton et al. (1980, p.49) states that “organization structure may be considered as the anatomy of the organization, providing a foundation within which the organization functions”. Hage and Aiken (1967) emphasize the importance of centralization of power, the degree of formalization, and the degree of complexity, when evaluating the structural characteristics of the organizations. Pugh and his associates (1968) operationalized formalization, centralization, specialization, standardization, and configuration as five primary dimensions of organization structure. Therefore, formalization is one of the essential and main factor for organizational analysis, when investigating the structuring of an organization.

Hage and Aiken (1967, p.79) define formalization as “the use of rules in an organization” and they operationalized it by two measures such as job codification and rule observation. Job codification shows the degree to which the job descriptions are specified, while rule observation indicates the degree to which employees are supervised in conforming to the standards established by job codification (Hage and Aiken, 1967). Pugh and his associates (1968) define formalization as the degree of written communications, instructions, rules and procedures in the organization. They split formalization into three subscales such as role definition (prescriptions of behavior like job descriptions), information passing documents (e.g. memo forms), and recording of role performance (e.g. records of inspection results) (Pugh et al., 1968). On the other hand, Bodewes (2002) mentions about the proper conceptual and operational definition of the formalization is a must for determining the true effect of formalization on outcomes such as organizational innovation. He emphasizes that formalization should be measured and defined collectively since it is composed of the interaction of both job codification and rule observation (Bodewes, 2002).

Adler and Borys (1996) evaluate formalization as a central feature of Weber's bureaucratic ideal type (e.g. Weber, 1947) and they mention about two conflicting views of the outcomes of bureaucracy. Based on the negative view, the bureaucratic form of organization decreases employee’s creativity and motivation, while increasing dissatisfaction (Adler and Borys, 1996). Some researchers (e.g. Burns and Stalker, 1961; Thompson, 1965) state that bureaucracy is an ineffective form of organization, when dealing with innovation and change. In a study of an electronics firm and a radio station, Rousseau (1978) reported that formalization positively related to physical and psychological stress, propensity to leave, absences and negatively related to innovation and job satisfaction. Nasurdin et al. (2006) reported that formalization and centralization have a positive influence on job stress among salespersons working in the stock broking industry. Dean et al. (1998) revealed that organizational formalization may aggravate organizational cynicism. According to Dekker and Barling (1995) employees may feel less valued in large organizations, where highly formalized policies and procedures can reduce organization’s flexibility in dealing with employees’ individual needs. Thus, large organizations, which are imparted by formal rules, could reduce POS (Rhoades and Eisenberger, 2002). Ambrose and Schminke (2003) report that organizational structure would moderate the relationship between procedural justice and POS. Their results demonstrate the stronger relationship between procedural justice and POS judgments in mechanistic organizations. Ambrose and Schminke’s (2003) results also show that mechanistic organization structures were negatively associated with POS. They state that mechanistic organizations are commonly perceived as less supportive than organic organizations.

On the other hand, positive view claims that formalization provides needed guidance, clarifies responsibilities, and helping employees be and feel more effective (Adler and Borys, 1996). Thus, formalization may decrease role conflict and ambiguity in organizations, which leads to employee work satisfaction and reduction in feelings of alienation and stress (e.g. Adler and Borys, 1996; Jackson and Schuler, 1985). Podsakoff et al. (1986) states that formalization reduced both role conflict and role ambiguity for both professionals and nonprofessional employees. They mention that formalization tends to reduce alienation through its ability to reduce role ambiguity and enhance organizational commitment. In a study of new ventures, Sine et al. (2006) reports that greater role formalization in founding teams increases new venture performance since formalization provides increased decision-making speed, credibility, legitimacy and decreased coordination costs (e.g. lower role ambiguity) for new ventures. Cosh, Fu, and Hughes (2012) report decentralized decision making, supported by a formal structure and written plans, provides the ability to innovate in most circumstances and is superior to other structures for a sample of small and medium sized enterprises. Mattes (2014) mentions about formalization and flexibilization do not contradict, but complement each other. She explains that formalization may go beyond the classical line organization and include some elements of flexibilization. Adler and Borys (1996) discuss the contradictory attitudinal effects of formalization based on whether it is viewed as constraining or enabling. According to Foss et al. (2015), formalization embodies structures and processes, which enables organizations to monitor the performance of individual organizational members. Also, they mention about a positive relationship exists between formalization and opportunity realization. Mayes et al. (2017) emphasizes that some objective types of HRM practices such as performance-based pay and equitable employee hiring may improve POS since these practices increase the reliance on formal rules and procedures in terms of merit.

Based on the above reasoning, one may expect that formalization, as an organization structure dimension may be a precondition of POS and may demonstrate a direct positive influence on POS. Therefore, the following hypothesis is put forth.

Trust is also an important factor for perceived organizational support research (e.g. Wong et al., 2012). Employees, who have been supported by their organization, are likely to develop trust in their organization. Thus, trust in organization may act as an antecedent of POS (e.g. Gilbert and Tang, 1998). Gilbert and Tang (1998, p.322) define organizational trust as “a feeling of confidence and support in an employer”. Schoorman et al. (2007, p.347) state that “trustor is willing to voluntarily take risks at the hands of the trustee”. Bachmann and Inkpen (2011) discuss that social actors in organizations have a tendency to be rule followers and they claim that the risk of unpredictable and untrustworthy behavior will be decreased, when rules exist. Likewise, Bachmann et al. (2015) mentions about the imposition of regulation and control mechanisms such as rules, policies, and process may help for the restoring trust in organizations. Krasman (2014) reports that formalization positively relates to subordinates’ perceptions of their supervisors’ trustworthiness and more strongly for subordinates who ranked higher on straightforwardness. Weibel et al. (2016) claims that organizational controls are positively related to employee trust in their organization, and only have a negative effect on trust when they are overly rigid, inconsistently applied or incentivize untrustworthy behavior. Shaw (1997) mentions that employees would perceive more support from their organization, when the organization creates a culture of trust in which organizational policies and procedures are consistent with employees’ expectations. As consistent with Shaw (1997), Wong et al. (2012) explains that employees tend to evaluate the organizational policies and procedures in a positive manner when they trust their organization, which will lead to an increase of employees’ perception of organization support. Therefore, the value of formalization to employees, and therefore its contribution to POS, may be influenced by employee perceptions regarding their trust to organization.

Thus, the following hypothesis is suggested.

Methodology

Research Goal

This research aims to examine the moderating role of trust in organization for the relationship between formalization and perceived organizational support. In order to test the research hypotheses, a field survey using questionnaires was employed.

Sample and Data Collection

The data of this study is collected via questionnaires from 343 airline-administrative support staff, which include secretaries, information technology personnel, finance and accounting staff, public relations, and other kinds of work associated with airline sector in Turkey. Survey questionnaires were distributed to 520 administrative support staff and a total of 352 questionnaires (68% response rate) were returned. Some of them were discarded due to the outliers and missing values, resulting 343 useable questionnaires in total. The sample featured mostly male (80%) respondents with means age and tenure of 38.11 and 14.54 years, respectively.

Measures

The constructs in this study are developed by using measurement scales adopted from prior studies. All scales except for trust in organization were evaluated by using five-point Likert scales, with anchors ranging from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (5). The trust in organization scale was evaluated with anchors ranging from lowest (1) to highest (5).

Formalization was evaluated by 6 items from Podsakoff and MacKenzie (1994). One item of the formalization scale was dropped due to the low factor loading. A sample item is “Clear, written goals and objectives exist for my job”. Alpha reliability of the formalization scale was 0.88.

Trust in organization includes both employees’ trust in the employing organization and their trust of the top management as consistent with Wong et al. (2012). To measure trust in organization, three items were adapted from Harris (1995)’s Organizational Culture Survey, with some modifications to render the items more suitable for the Turkish context. A sample item is “I generally trust top management”. Alpha reliability of this scale was 0.89.

Perceived organizational support was evaluated by 8 items (e.g. Eisenberger et al., 1990) from the survey of perceived organizational support (SPOS) developed by Eisenberger et al. (1986). A sample item is ‘‘The organization really cares about my well-being’’. Alpha reliability of the SPOS was 0.91.

The fit statistics of the latent model, which is composed of formalization, trust in organization, and perceived organizational support scales, show that the model has an adequate fit (χ2/df = 3.08; CFI= 0.95; GFI=0.90 RMSEA=0.07).

Findings

Table

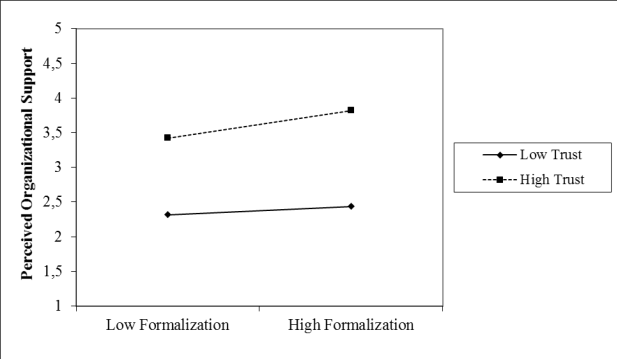

Our research hypotheses were tested by using hierarchical moderated regression analyses and correlation analysis. Aiken & West’s (1991) methodology was employed in order to measure the moderation effect of trust in organization. First, we entered the mean centered formalization, and trust in organization to the regression models in order to reduce multicollinearity. Then, we entered the interaction term formed by multiplying the mean centered formalization, and trust in organization (e.g. Aiken & West, 1991). The moderator hypothesis will be supported if the interaction term is significant. Further, we checked whether the increase in R2 is also statistically significant or not, which would bring more evidence in favor of the moderator effect of trust in organization.

Table

Discussion

This study tries to make contribution to the relevant research stream by enhancing our understanding of employees’ perceptions of organizational support, formalization as a dimension of organization structure, and trust in organization in the Turkish context. In the existing literature, the relationship between formalization and POS is unclear and some inconsistent findings are reported. Thus, this study initially investigated the direct effect of formalization on perceptions of organizational support. Results reveal that formalization positively affected POS, which is consistent with Cosh et al. (2012), Adler and Borys (1996), and Podsakoff et al. (1986)’s findings. Employees working in airline organizations may benefit from written rules and procedures governing their activities since their role conflict and ambiguity will be decreased by the help of formalized structures. Further, as discussed by Mattes (2014), formalization may include some degree of flexibilization. Thus, such rules and process may not limit employee’s freedom of action, instead, they can be a resource for proactively designing the employee activities in organization. Further, employees of airline organizations like the employees of medical or governmental organizations may evaluate formalization as a technical nature of their work, where formalized rules and regulations tend to decrease their role conflict (e.g. Podsakoff et al., 1986). Also, in formalized organizations, since managers’ behaviour is shaped with established rules and procedures, their own discretion will be limited, which may decrease organizational politics in decision-making, unfair and biased behaviours at work and promote the perceptions of justice (e.g. Krasman, 2014, and Mayes et al., 2017). Based on these arguments, formalized structure can canalize social exchange and may be an effective instrument to increase the perception of organizational support.

Another important contribution of this study to the existing literature is the finding of moderating effect of trust in in organization for the relationship between formalization and POS. The results show that the relationship between formalization and POS is stronger when trust in organization is high than when it is low. This result is in line with Wong et al. (2012) and Shaw (1997)’s explanations about trust’s role in organizations. When organization creates a culture of trust, employees will treat formalized structure (e.g. standardized rules and procedures) much more positively since it will be probably perceived as more enabling rather than coercive (e.g. Adler and Borys,1996), which will lead to an increase in perception of organizational support. Further, formalized structure will be evaluated as a protective mechanism for employees since it reduces the risk and vulnerability (e.g. Weibel et al., 2016) of them when they trust in organization. All of these will facilitate the development of POS.

Some managerial strategies can be applied. Formalization, which is inevitable for many kinds of work, is a relevant factor to consider in the context of POS. However, managers may implement such formal rules and procedures in a flexible way, as suggested by Mattes (2014). Thus, during the strategy implementation stage of strategic management process, formalized structure of the organization may be constructed by taking a controlled degree of flexibility into consideration. Also, managers should promote a culture of trust in their organizations. Managers should exert trust building efforts such as implications of fair policies, procedures and effective reward system in order to strengthen the formalization-POS relationship.

References

- Adler, P. S. and Borys, B. (1996). Two Types of Bureaucracy: Enabling and Coercive. Administrative Science Quarterly, 41(1), 61-89.

- Aiken, L. S., & West, S. G. (1991). Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

- Ambrose, M. L., & Schminke, M. (2003). Organization structure as a moderator of the relationship between procedural justice, interactional justice, perceived organizational support, and supervisory trust. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(2), 295.

- Armeli, S., Eisenberger, R., Fasolo, P., & Lynch, P. (1998). Perceived organizational support and police performance: The moderating influence

- Bachmann, R., & Inkpen, A. (2011). Understanding institutional-based trust building processes in interorganizational relationships. Organization Studies, 32(2), 281-301.

- Bachmann, R., Gillespie, N., & Priem, R. (2015). Repairing Trust in Organizations and Institutions: Toward a Conceptual Framework. Organization Studies, 36(9), 1123-1142.

- Blau, P. M. (1964). Exchange and power in social life. New York: Wiley.

- Bodewes, W. E. (2002). Formalization and innovation revisited. European Journal of Innovation Management, 5(4), 214-223.

- Burns, T., and Stalker, G. M. (1961). The Management of Innovation. London: Tavistock.

- Cosh, A., Fu, X., & Hughes, A. (2012). Organisation structure and innovation performance in different environments. Small Business Economics, 39(2), 301-317.

- Dean, J.W., Brandes, P. & Dharwadkar, R (1998). Organizational cynicism. Academy of Management Review, 23 (2), 341-352.

- Dekker, I., & Barling, J. (1995). Workforce size and work-related role stress. Work and Stress, 9, 45-54.

- Eisenberger, R., Armeli, S., Rexwinkel, B., Lynch, P. D., & Rhoades, L. (2001). Reciprocation of perceived organizational support. Journal of applied psychology, 86(1), 42.

- Einsenberger, R., Cummings, J., Armeli, S., & Lynch, P. (1997). Perceived organizational support, discretionary treatment, and job satisfaction. Journal of Applied Psychology, 82(5), 812-820.

- Eisenberger, R., Fasolo, P., & Davis-LaMastro, V. (1990). Perceived organizational support and employee diligence, commitment, and innovation. Journal of Applied Psychology, 75(1), 51-59.

- Eisenberger, R., Huntington, R., Hutchison, S., & Sowa, D. (1986). Perceived organizational support. Journal of Applied Psychology, 71(3), 500-507.

- Foss, N. J., Lyngsie, J., & Zahra, S. A. (2015). Organizational design correlates of entrepreneurship: The roles of decentralization and formalization for opportunity discovery and realization. Strategic Organization, 13(1), 32-60.

- Gilbert, J.A., and Tang, T. (1998). An Examination of Organisational Trust Antecedents, Public Personnel Management, 27, 321-338.

- Gouldner, A. W. (1960). The norm of reciprocity: A preliminary statement. American Sociological Review, 25, 161-178.

- Hage, J., & Aiken, M. (1967). Relationship of centralization to other structural properties. Administrative Science Quarterly, 72-92.

- Harris, P. R. (1995). 20 Reproducible Assessment Instruments for the New Work Culture. HRD Press, Amherst, Massachusetts.

- Jackson, S. E., and Schuler, R. S. (1985). A meta-analysis and conceptual critique of research on role ambiguity and role conflict in work settings. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 36, 17-78.

- Kim, K. Y., Eisenberger, R., & Baik, K. (2016). Perceived organizational support and affective organizational commitment: Moderating influence of perceived organizational competence. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 37, 558-583.

- Kinnunen, U., Feldt, T., & Makikangas, A. (2008). Testing the effort-reward imbalance model among Finnish managers: The role of perceived organizational support. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 13(2), 114-127.

- Krasman, J. (2014). Do my staff trust me? The influence of organizational structure on subordinate perceptions of supervisor trustworthiness. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 35(5), 470-488.

- Lam, L. W., Liu, Y., & Loi, R. (2016). Looking intra-organizationally for identity cues: Whether perceived organizational support shapes employees’ organizational identification. Human Relations, 69(2), 345-367.

- Mattes, J. (2014). Formalisation and flexibilisation in organisations-Dynamic and selective approaches in corporate innovation processes. European Management Journal, 32(3), 475-486.

- Mayes, B. T., Finney, T. G., Johnson, T. W., Shen, J., & Yi, L. (2017). The effect of human resource practices on perceived organizational support in the People’s Republic of China. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 28(9), 1261-1290.

- Nasurdin, M. A., Ramayah, T., & Yeoh, C. B. (2006). Organizational structure and organizational climate as potential predictors of job stress: Evidence from Malaysia. International Journal of Commerce & Management, 16(2), 116-129. of socioemotional needs. Journal of Applied Psychology, 83, 288-297.

- Paillé, P., & Raineri, N. (2015). Linking perceived corporate environmental policies and employees eco-initiatives: The influence of perceived organizational support and psychological contract breach. Journal of Business Research, 68(11), 2404-2411.

- Podsakoff, P. M., & MacKenzie, S. B. (1994). An examination of the psychometric properties and nomological validity of some revised and reduced substitutes for leadership scales. Journal of Applied Psychology, 79(5), 702.

- Podsakoff, P. M., Williams, L. J., & Todor, W. D. (1986). Effects of organizational formalization on alienation among professionals and nonprofessionals. Academy of Management Journal, 29(4), 820-831.

- Porter, L.W. & Lawler, E.E. (1965). Properties of Organizational Structure in Relation to Job Attitudes and Behavior. Psychological Bulletin, 64 (1), 23-51.

- Pugh, D. S., Hickson, D. J., Hinings, C. R., & Turner, C. (1968). Dimensions of organization structure. Administrative science quarterly, 65-105.

- Rhoades, L., & Eisenberger, R. (2002). Perceived organizational support: A review of the literature. Journal of applied psychology, 87(4), 698.

- Rousseau, D. M. (1978). Characteristics of departments, positions and individuals: Contexts for attitudes and behavior. Administrative Science Quarterly, 23, 521-540.

- Schoorman, F. D., Mayer, R. C., & Davis, J. H. (2007). An integrative model of organizational trust: Past, present, and future. Academy of Management review, 32(2), 344-354.

- Shaw, R.B. (1997), Trust in the Balance: Building Successful Organisations on Results, Integrity, and Concern, San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass Publishers.

- Shen, Y., Jackson, T., Ding, C., Yuan, D., Zhao, L., Dou, Y., & Zhang, Q. (2014). Linking perceived organizational support with employee work outcomes in a Chinese context: Organizational identification as a mediator. European Management Journal, 32(3), 406-412.

- Sine, W. D., Mitsuhashi, H., & Kirsch, D. A. (2006). Revisiting Burns and Stalker: Formal structure and new venture performance in emerging economic sectors. Academy of Management Journal, 49(1), 121-132.

- Thompson, V. A. (1965). Bureaucracy and innovation. Administrative Science Quarterly, 10, 1-20.

- Weber, M. (1947). The theory of social and economic organization [A. M. Henderson & T. Parsons, trans.]. New York: Oxford.

- Weibel, A., Den Hartog, D. N., Gillespie, N., Searle, R., Six, F., & Skinner, D. (2016). How do controls impact employee trust in the employer? Human Resource Management. 55 (3), 437-462

- Wong, Y. T., Wong, C. S., & Ngo, H. Y. (2012). The effects of trust in organisation and perceived organisational support on organisational citizenship behaviour: a test of three competing models. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 23(2), 278-293.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

20 December 2017

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-033-4

Publisher

Future Academy

Volume

34

Print ISBN (optional)

--

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-442

Subjects

Business, business studies, innovation

Cite this article as:

Bitmiş, M. G., Ergeneli, A., & Oktay, F. (2017). Moderating Role of Trust on Relationship Between Formalization and Perceived Organizational Support. In M. Özşahin (Ed.), Strategic Management of Corporate Sustainability, Social Responsibility and Innovativeness, vol 34. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 206-215). Future Academy. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2017.12.02.18