Abstract

Socio-emotional Learning (SEL) provides individuals with strategies and skills that allow them to be able to identify their own emotions, to reflect on their causes and to understand how these emotions condition their behaviour, aiming at their regulation (

Keywords: Socio-emotional CompetenceIntellectual DisabilityIntervention Programme

Introduction

Emotions play a key role in the individuals’ learning and development, preparing them to deal quickly and effectively with various situations besides functioning as alert mechanisms that continually evaluate the surrounding environment and identify when something important for the wellbeing or survival (Ekman, 2003).

Throughout his development, the individual is learning and expanding his ability to understand, both the causes and the functions of one’s own emotions, as well as recognizing the several emotional experiences (Denham, 2006). This learning provides the individual with strategies and skills that allow him to show himself that he is able to identify his emotions, to reflect on their causes and to understand how these emotions condition his behaviour, aiming at their regulation. Therefore, and considering their importance, these skills should be considered and developed early on awakening children to the importance that the emotions and the ability to recognize and regulate them in a guided and positive way exert on their development process (Mayer & Salovey, 1999).

If intervention programmes are shown to be effective with children without any type of problem, more they will be with children with Intellectual Disability (ID) since they understand more than they can express and feel their emotions spontaneously, being able to modify them in knowledge, not always orally expressed (Damásio, 2001). That was the main reason for the creation of

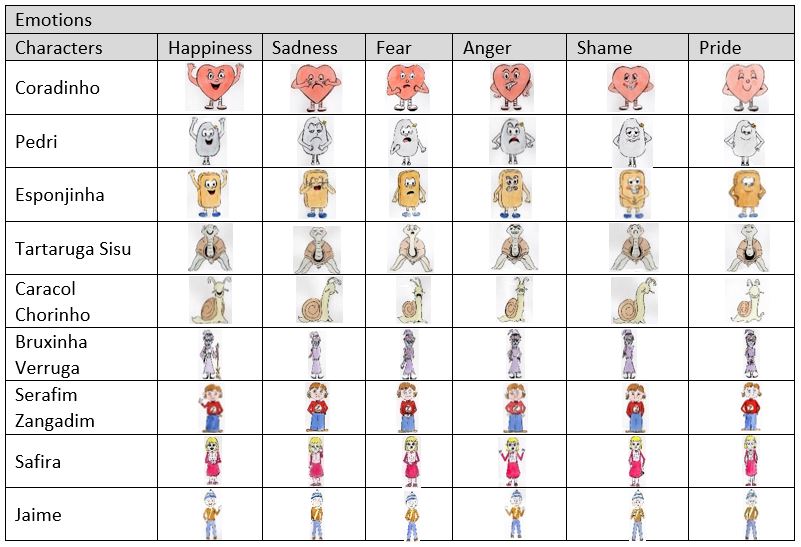

The emotions to be worked in the program include happiness, sadness, fear, anger, shame and pride, being the first four basic emotions that do not raise many difficulties in their recognition and expression by children with ID. Shame and pride, being social emotions, integrate components of the primary emotions and are biologically determined, but also socially learned (Damásio, 2000). They are more difficult to identify, more complex and allow to assess more accurately the identification, expression and regulation of emotions by the children with ID.

Problem Statement

SEL involves the processes through which children acquire and effectively apply the knowledge, attitudes, and skills necessary to understand and manage emotions, set and achieve positive goals, feel and show empathy for others, establish and maintain positive relationships, and make responsible decisions (CASEL, 2008). Programmes on SEC lead schools to be more successful in their educational mission which is particularly important for children with ID due to their characteristics and limitations.

Emotions and Socio-emotional Competences

"Emotion", as the term "cognition", refers to a set of subjective reactions to an event protruding from the internal and external environment of the organism, characterized by physiological, experiential and behavioural changes. Emotions directly contribute to the functioning of the perceptive, cognitive and personality systems, as well as for the development of SEC (Izard, 2001; Lewis, 2008).

Empirical studies have demonstrated the importance of SEC for academic performance (Denham, 2006). Children entering school with more positive profiles of SEC not only have more success in developing positive attitudes towards school as significantly improve their performance and achievement (Ladd, Birch, & Buhs, 1999; Denham, 2006).

Saarni (2008) defines SEC as the demonstration of emotional self-efficacy in social relationships that evoke emotion. This definition demystifies the complexity of emotional competence and talks about personal efficacy applied to social relationships as being the ability to achieve a desired result. Our whole social relationship influences our emotions and, in turn, our emotions influence our relationships (Vale, 2009). Saarni (1999, 2008) also argues that because emotional competence is linked to concepts such as compassion, self-control, justice and a sense of reciprocity, we also can’t separate emotional competence from the moral sense.

Although SEC is considered from a perspective of personal experience, the fact is that it is lived in interaction with others. Emotions are inherently social in at least three aspects: in terms of interpersonal nature of emotions, the individual behaviour of others in the group determines the emotion that the child will have; also when a child displays an emotion, either in group or in dual situation, the expressivity is an important information that he conveys, not only to himself, but to the other members of the group; finally, the expression of an emotion can serve as a condition for the experience and expression of others’ emotions as social interactions and relationships are guided and defined by the emotional transactions within the group (Campos & Barrett, 1984; Parke, 1994; Saarni, 1999; Denham, 2006).

In the late twentieth century, the concern about the child's emotional function increased significantly, especially in the skills used to think and regulate emotions. In this way, the concept of emotional competence grew alongside with various models of emotional intelligence. One of these was that of Mayer and Salovey (1999) and Mayer, Salovey and Caruso (2000) which proposes the processing of information elements (perception, evaluation and emotional expression) integrated with cognitive/affective elements (analysis and understanding of emotion with cognitive dexterity and vice versa) and with aspects of a skill or performance (the ability to regulate their own emotions and those of others).

The concept of SEC was derived from the thinking of authors such as Denham (2007). This concept implies the acquisition of skills underlying the expression of emotions, socially appropriate regulation and emotional knowledge, being implicitly related to the identity, personal history and with the socio-moral development of the child and teenager. It is considered a central competence in the ability of children and young people to interact, self-regulate and establish rewarding relationships with others, in the management of affection at the beginning and in the continuity of the evolutionary involvement with the pairs.

In a school context, these tasks and outcomes may include school success, meet personal and emotional needs and develop transferable skills and attitudes beyond school. Through thought and feeling socially competent people are able to select and control the behaviours to emit and to suppress in a particular context, to achieve the objectives set by themselves, or established by others.

Emotions are primary sources of knowledge, playing a preponderant role in adapting the individual to the environment, being the initiators of the learning process (Damásio, 2001). Thus, however great the cognitive limitations of the individual, he can interact with the world through his basic emotions.

Studies show that individuals with ID can confidently identify their own emotions and recognize the emotional expressions in others (Moore, 2001; McClure, Hapern, Wolper & Donahue 2009). However, Bremejo (2006) considers that this identification has many flaws and gaps when compared with children without ID, being evident a greater difficulty in identifying shame and anger (Sovner & Hurley, 1986; Pereira & Faria, 2015). These authors point out that individuals with ID demonstrate difficulties in organization and coping strategies. This difficulty in adaptively managing some situations leads to some anxiety, which can be attenuated with the implementation of an intervention programme.

Socio-emotional Learning

SEC can be properly developed through the process of SEL corresponding to the knowledge, attitudes and skills that each one must consolidate to make coherent choices with himself, have gratifying interpersonal relationships and a socially responsible and ethical behaviour (CASEL, 2013).

The programmes of personal and social competences have emerged in psychiatry, having subsequently been used by other areas of knowledge, with other populations. The simplicity of this type of strategy favoured its expansion for the training of professionals from other areas, namely teachers (Matos, 1998), giving place, later on, to the programmes of social and emotional competences.

SEL refers to a model whose type of activities allows the acquisition of skills that all people need to adapt to different situations and activities of daily life, to be successful in their life project, whether in the family, school, workplace or in relationship with others (Durlak, Weissberg, Dymnicki,Taylor, & Schellinger, 2011). It is a process in which subjects have the possibility to recognize and regulate their emotions, make responsible decisions, establish positive relationships with others and become individually healthier and more productive (Zins, Bloodworth, Weissberg & Walberg, 2004).

Being evident the advantages of SEL in children without ID, likewise they will be in children with Special Education Needs (SEN), including ID.

In the inclusive school paradigm, the differences regarding the specificities of each individual and the need for adequate responses, providing equal opportunities, assume great relevance (Borges & Coelho, 2015). According to César (2003) for many children and teenagers attending school, as we currently conceive it, the sense that the school seems to have been made to the measure of others, based on a culture very distant from the one in which they are inserted, is a constant.

A school for all presupposes equal opportunities, a common starting point with the necessary adaptations along the way. The teaching and learning processes may undergo various obstacles that refer to students but also to teachers who have to manage the difficulties arising from the inclusion of students with marked differences in the same context (Sim-Sim, 2005).

The academic success depends on several factors, among them the teachers' taste for teaching and the passion for the learning progress, being expected to transmit students their enthusiasm, arousing the passion for what they learn. The teacher not only teaches, but he also knows how to do something and what he knows to do is not only to teach; it consists essentially of helping people to grow and develop the potential that they all have, in configurations and diversified degrees (Abreu, 1996). The same author stresses that supporting students in the acquisition of SEC should be another great challenge of teacher intervention, considering that one can no longer take refuge in a teaching-learning relationship based on the transmission of knowledge but rather be recognized as a human development agent.

With the implementation of programmes to promote SEC academic success will be a reality and this way schools will be more successful in their educational mission (Elias et al., 1997). In addition, these programmes ensure meaningful learning at the level of SEC that promote friendly relations with peers, or that prevent difficulties in interactions with others (Ladd, Herald & Andrews, 2006).

Research Questions

The goals of SEL programming are to promote students’ social-emotional skills and positive attitudes, which, in turn, should lead to improved adjustment and academic performance as reflected in more positive social behaviours, fewer conduct problems, less emotional distress, and better grades and achievement test scores (CASEL, 2008).

Based on the assumption that all children benefit from SEL, it is imperative to create a programme based on short stories and illustrations, considering their benefits in children’s development, aiming to promote the identification and management of emotions in children with ID, since SEC programmes directed for this population are still scarce.

Taking into account the wide range of advantages of SEL programming it is important to understand and verify if the objectives and the contents of

Purpose of the Study

Based on a consistent theoretical background that focuses on programmes to promote SEC, this study aims to describe the creation and validation of the emotional content of each illustration and story for a new intervention programme directed to children with ID. The programme is built around these short stories properly illustrated, making use of several playful-didactic materials to be implemented throughout 8 sessions, being that each session should last between 30-40 minutes.

The main purpose of the study is the programme’s construction and validation by experts in emotional development and children’s literature, and by children with and without ID. It was made a pilot study with 3 groups of 7 subjects each with the purpose of verifying the suitability of contents and objectives to young people and children with ID.

Research Methods

Taking into account the need to deepen the knowledge of effective programmes on SEC it was made a systematic literature review on programmes highlighting their strengths, their advantages as well as their weaknesses and flaws. Alongside this, it was built a new programme based on the assumptions of SEC programmes, that aims to promote these competences in children with ID, following and respecting the several stages needed to validate it as an effective instrument.

It is also a descriptive type of quantitative research, where the relative frequencies were calculated for each emotional expression presented by the characters, and the pilot study sample of 21 subjects was characterized.

Programmes to promote SEC

The development of SEC, considered a basic competence for life, leads to SEL. It is urgent to define goals, establish contents, plan activities and intervention strategies to design intervention programmes in order to be studied and evaluated (Bisquerra, 2003).

Programmes dedicated to the development of SEC should involve: the self-knowledge, that is, the ability that children develop to identify in emotional experiences their own emotions, thoughts and the way they act on their behaviour; self-regulation which translates into the children's ability to learn to regulate their emotions, controlling their impulses and motivating themselves to overcome these same situations; social awareness, translated into the ability to take an empathic perspective on others and recognize them as support resources; relationships management which is the ability to develop and maintain healthy relationships and conscious decision-making, that is, the ability to make decisions in a responsible and constructive way taking into account ethical and social standards (CASEL, 2008).

The abovementioned programmes, to be considered as quality ones, should emphasize cognitive, affective and behavioural competences (Vale, 2012). Since these competences represent the first step towards SEL they need to be taught and students should be motivated for their learning and daily use. Therefore, another of the quality factors of a programme lies precisely in teaching strategies, which should include competency-based modelling, provide students with opportunities to practise these new skills and give feedback and reinforcement (Hawkins, 1997, quoted by Graczyk, Weissberg, Payton, Elias, Greenberg, & Zins, 2000). Children should be seen as active learners and employ interactive strategies. Thus, the techniques to be trained should make use of methodologies that privilege group work, cooperative learning, role-play and thematic discussions (Dusenbury, Falco, Lake, Brannigan & Bosworth, 1997, quoted by Graczyk et al., 2000). Through dialogue, the teacher should encourage children to think about situations, to become aware of their emotions, to generate strategies to successfully solve the problem.

An aspect of great importance is emphasized by the Collaborative for Academic Social and Emotional Learning (CASEL, 2003) by arguing that programmes should be for all students and not only for those with risky behaviours, because all benefit from socio-emotional development. In this way, it is also important to emphasize their importance to children with ID, even because the existence of programmes directed to this population is still scarce (Faria, 2016). The intensity of the programmes implementation is not of minor importance. The studies argue that the activities that are part of the programmes should be practised weekly and not sporadically, presenting a sequence and not isolated activities (Vale, 2012; CASEL, 2003).

Short stories as part of programmes to promote SEC

"Little Red Riding Hood was my first love. I felt that if I could have married her, I would have known true happiness.” This statement by Charles Dickens indicates that he, as countless millions of children throughout the world and through the ages, had also been enchanted by fairy tales (Bettelheim, 1976).

The word

Children will benefit if the involved activities have stories as the main base since while it distracts them, the tale elucidates them on themselves and promotes the development of their personality. Bettelheim (1976) states that the tale has so many meanings, on so many levels, and enriches the child's existence in so many ways, that any book is able to match the amount and diversity of contributions that tales bring to the child.

The tale gives voice to all the fears that the subject has to face, like rivalries, taboos, struggles, the fear of death, of growth, of everything that is unknown; meets the loves, the hatreds, the distrust and the joy, the persecution and the happiness, displaying, in an exemplary manner, the struggles between good and evil, between the allowed and the forbidden, between the victories and the disappointments of the subject. It also meets the child’s animist thinking and reality allowing him to fully trust what the tale reports. As the world of tales agrees with his, it can reassure his fears (Santos, 2002). Moreover, the unrealistic nature of tales is important because it makes it obvious that the purpose of short stories is not to give useful information about the outside world, but rather on the inner psychological processes that take place in an individual (Bettelheim, 1976).

Thus, the tale serves the child in a perfect way. First because it is a wonderful entertainment, then because it tells about the triumph of the weakest, the smallest, the youngest or even the ugliest. This disconcert satisfies the child as it meets his most primal desires. In the stories special contours are outlined, time is marked, characters are defined, rhythms are instilled, future designs are announced, possible worlds are built. Also, values, behaviours, attitudes and the existence of a particular social order are defined. It is promoted the development of imagination, observation, memory and knowledge (Santos, 2006).

Albuquerque (2000) states that for all its characteristics, the tale is an important organizer of affections, containing emotions and feelings, allowing the child a permanent dynamic construction.

Telling and hearing stories comes close to a magical act, able to marvel children, to leave them amazed at the art of simplicity, to make them fun with weird combinations, to leave them perplexed because they find characters of their age with so many problems, to leave them with doubts about tolerance, the right to difference, able to put them to think (Sousa, 2000).

It seems evident that are the affective factors that allow the child to give the world and life a systematization, using its fantasy potential with an affective function of world reconciliation and order. In many circumstances imagery and the use of meaningful images emerge as a form of knowledge integration (Albuquerque, 2000; Santos, 2006). It is with the entrance in the first cycle of the basic education, the beginning of scholar path, between the 5 and the 6 years, that children begin to identify themselves with the story: they listen to it and try to control the narration by integrating new knowledge with previous one. At this stage children are ready to tell the story, expressing enthusiasm for doing so. It is important to recognize that as a natural form of narration, the retelling is always a revision and affirmation that the knowledge is consolidated, although the child always tries to make some changes, but always demonstrating that he understands the story in its depth (Martins, 2000). Around 7 years old, the child brings the characters of the imaginary to the real plane using dialogues between the characters similar to those in his daily life, opting for a plot type more similar to the real world, suppressing some aspects inherent in the fantastic, but always using symbolization and the power of abstraction that he inherited from the phase of the primacy of fantasy (Azevedo, 2006).

The tale is of great structuring importance transmitting the child models for the understanding of their conflicts and anxieties, suggesting examples of solution, temporary or permanent, showing that fighting difficulties of life is inevitable, but that it is possible to overcome them (Tompkins, Guo & Justice, 2013). Interaction with stories awakens emotions in children as if they are experiencing them, allowing through imagination to exercise problem-solving ability that arise in their daily lives (Souza & Bernardino, 2011).

Stories may be a privileged strategy for children to work on their emotions and understand others’. Gavazzi and Ornaghi (2011) explored what happens when children do not only hear stories that contain many words that describe emotions, but have also the opportunity to reflect on the meaning of these words along with other children, under the guidance of an adult. It was found that the active use of these terms in daily conversations increased children's competence in understanding their emotions.

According to Castro (2008) the child, with his imaginary wealth and his ability to experience the make-believe, plunges into a charming universe, where they deal with feelings of good and evil, where characters such as fairies, witches, stepmothers, princes and princesses may appear. In this way, the child identifies emotions as sadness, anger, insecurity, happiness, tranquillity, anguish, anxiety and fear, being through the exercise of make-believe that he deals with his feelings and imaginations with less anguish.

According to Guhur (2007) individuals with ID present a form of nonverbal expression signalling affective states that may be result of the absence of symbolic resource to express themselves. Thus, in contexts of intervention, they may present a compulsive laughter as a way to regulate the shame. It is also worth noting the predominant way of expressing affectivity through organic expression in which it is the body itself to reveal the emotions through gestures, postures and silences. This mode of exteriorization of emotions demonstrates the little knowledge that some individuals have of the linguistic resources so the researcher must be alert to all non-verbal language (Pereira & Faria, 2015).

Findings

As it was mentioned, SEL benefits all students since all benefit from socio-emotional development. It is important to emphasize their importance to children with ID because there is a lack of programmes directed to this population. The programme

The construction of the programme Smile, Cry, Scream and Blush

Whatever our age, only a story that conforms to the principles underlying our thinking has the power to convince us. If this is so for adults, it is truer for children, for their animistic way of thinking (Bettelheim 1976).

Through adult intervention, narratives appear as strategies for the achievement of learning the level of writing, language, increased vocabulary, speaking and as a way of acquiring values and concepts. The description of the stories, aided by the visualization of symbols, stimulates the child's creativity and imagination while arouses his curiosity, exteriorizes emotions and helps to resolve conflicts through the game of make-believe. The diversity of contents, the way they are reported and the very language of tales are considered to be relevant in cognitive and emotional development as well as on the child’s personality formation (Couto, 2003; Souza & Bernardino, 2011).

Based on a bibliographical review that focuses on programmes that aim to promote SEC, and based on the assumptions above the Programme

Three mascots have been created to accompany the programme over its eight sessions:

All sessions begin with a short story having as main characters one, two or the three mascots. After a motivational dialogue, the session continues with a second story focusing on one of the emotions to be worked and with a main character, animal or human. Thus, the programme was built around short stories, illustrated and with simple language, whose excerpts are in table

The illustrations were validated, initially by seven experts in the area of emotional development and children's literature, and in a second phase by a group of 20 subjects with ID, aged between 8 and 20 years old and by a group of 20 subjects without ID with the same ages. They were asked to express their views on each of the characters' expressions, indicating whether they agreed or not, with

Through Table

The programme is applied in groups of 7 or 8 children, in school environment and in sessions of about 30 to 40 minutes. It covers 8 sessions where six emotions are worked through materials such as the wheel of emotions or the silhouette of the characters, as it can be seen in table

It should be noted that the first session gives a brief overview of all the emotions that will be worked in the following sessions: happiness, sadness, fear, anger, shame and pride; the eighth and last session also addresses all the emotions and it is made a consolidation of all the work developed, reminding all the characters in the programme, asking children which ones they liked the most, which ones they liked the least, with which characters they identified, which were completely different from them, what they would change in the stories, etc. In this session, in addition to activities similar to previous sessions it will be important to make use of a mirror and ask children to express emotions and compare them with those of their colleagues and also to try to guess their colleagues’ emotions. It will be an important session to systematize all the work developed throughout the programme.

Thus, the application of the programme follows a linear structure, as it can be seen in table

The materials used are of easy access and handling. The investigator may choose to tell the stories through a book in which the illustrations should be presented in an appropriate size so that all can see clearly, or through a projector, since the programme can be made available in digital format. The materials to be used after reading and interpreting the short stories are photocopiable, namely the characters' silhouettes for the children to draw, the cards with the characters expressing the various emotions as well as the wheels of emotions.

Each of the sessions follows a guiding structure of the procedures to be followed. This structure describes specific objectives, warming up activities, activities to be carried out during the session and procedures as can be seen in table

Following all the previous assumptions, objectives and the structure designed, it was peremptory to make a pilot study with the programme

It was used a sample of 21 subjects with ID divided in three groups of 7 and attending three different schools from two Portuguese cities, Castelo Branco and Abrantes. The average age was 9,2 as two groups were attending years 3 and 4 and one group was attending year 5 of elementary school. The programme was implemented and worked over eight weeks with one session per week and the children’s involvement was notorious and increasing week after week. The characters and the stories remained in most of children’s memory as they kept talking about them until the end of the intervention.

With the pilot study, it was observed that throughout the programme there were no problems raised by children so it was not necessary to make changes. It seems clear that the eight sessions were enough, as well as the time of each session, the instructions were clear, the short stories were easy to understand due to their simplistic language, and the illustrations were appealing and clear in expressing the emotions.

Conclusion

Emotional education is an educational process, continuous and permanent, which aims to promote the development of SEC as an essential element of human development and for the purpose of increasing personal and social well-being (Bisquerra, 2000, quoted by Bisquerra, 2003). The intervention programmes in this area should follow an eminently practical methodology, with group dynamics, self-reflection, dialogues and games.

Knowing that the learning of SEC is a key element for a healthy development, it is believed that a preventive intervention from the emotional development point of view, which promote these competences, makes perfect sense among young children, with and without ID, translating into their personal and social well-being (Almeida & Araújo, 2014).

The programme

Starting from the assumptions on which the programmes of promotion of SEC are based and considering this learning as essential to education, the programme

References

- Abreu, V. (1996). Pais, Professores e Psicólogos. Coimbra Editora: Coimbra.

- Albuquerque, F. (2000). A Hora do Conto. Lisboa: Edições Teorema.

- Almeida, S. L. & Araújo, M. A. (2014). Aprendizagem e sucesso escolar: Variáveis pessoais dos alunos. Psicologia e Educação: Braga.

- Azevedo, F. (2006). Educar para a literacia, para uma visão global, integradora da língua materna. In F. AZEVEDO (coord), Língua Materna e Literatura Infantil. Elementos Nucleares para Professores do Ensino Básico. Lisboa: Lidel.

- Bettelheim, B. (1976). Psicanálise dos contos de fadas. 10ªedição. Lisboa. Bertrand Editora

- Bisquerra, R. (2003). Educación emocional y competencias básicas para la vida. Revista de Investigación Educativa. 21 (1), 7-43

- Borges, I., Coelho, A. (2015). O papel dos pares na inclusão de alunos com NEE: programa PARES. EXEDRA-Revista Científica da Escola Superior de Educação de Coimbra. (Número Temático). 11-26

- Bruder, M. (2000). El cuento y los afectos. Buenos Aires. Galerna.

- Brunner, J. (1986). Actual minds, possible worlds. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Campos, J., & Barrett, K. (1984). Toward a new understanding of emotions and their development. In C. Izard, J. Kagan & R. Zaionc (Eds.). Emotions, Cognition & Behaviour. New York: Cambridge University Press. 229-263

- Casel (2013). Collaborative for academic, social and emotional learning. SEL impact on students. New York: Casel; [acesso em 2017 abr 10]. Disponível em http://casel.org/wp-content/ uploads/CS_Impacts.pdf

- Castro (2008). Diálogos entre literatura clássica infantil e psicanálise. CES Revista. Juiz de Fora. 22. 267-281

- César, M. (2003). A escola inclusiva enquanto espaço-tempo de diálogo de todos e para todos. In D. Rodrigues (Org.), Perspetivas sobre a inclusão. Da educação à sociedade. Porto: Porto Editora. 117-149

- Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning (2008). Social and emotional learning (SEL) and student benefits: Implications for the Safe Schools/ Healthy Students Core Elements. Report. Acedido em 13/04/2017 de http://www.casel.org

- Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning (CASEL). (2003). Safe and Sound. An Educational Leader’s Guide to Evidence-Based Social and Emotional Learning (SEL) Programs. Published in Cooperation with the Mid-Atlantic Regional Educational Laboratory The Laboratory for Student Success.

- Couto, J. M. A. (2003). Potencialidades Pedagógicas e Dramáticas da Literatura Infantil e Tradicional Oral. A Criança, a Língua e o Texto Literário: Da Investigação às Práticas – Atas do Iº Encontro Internacional. Braga: Universidade do Minho – Instituto de estudos da criança. pp 209-223

- Damásio, A. (2000). O Sentimento de Si. O corpo, a emoção e a neurobiologia da consciência. 6ª edição. Mem-Martins: Publicações Europa-América

- Damásio, A. (2001). Fundamental feelings. Nature. 413. 781

- Denham, S. (2007). Dealing with feelings: how children negotiate the worlds of emotions and social relationships. Cognition, Brain, Behaviour, 11 (1), 1-48.

- Denham, S. A. (2006). Social-emotional Competence as Support for School Readiness: What is it and how do we assess it? Early Education and Development. 17(1), 57 – 89.

- Durlak, J., Weissberg, R. , Dymnicki, A., Taylor, R., & Schellinger, K. (2011). The impact of Enhancing Students` Social and Emotional Learning: A Meta-Analysis of School-Based Universal Interventions. Journal of Child Development, 82, 405-432.

- Ekman, P. (2003). Emotions revealed: Recognizing faces and feelings to improve communication and emotional life. New York: Times Books

- Elias, M. J., Zins, J. E., Weissberg, R. P., Frey, K. S., Greenberg, M. T., Haynes, N. M., Kessler, R., Schwab-Stone, M. E., & Shriver, T. P. (1997). Promoting social and emotional learning: Guidelines for educators. Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

- Faria, S., Esgalhado, G., Pereira, C. (2016). Measurements to Assess and Programmes to Promote Socio-emotional Competences in Children with Intellectual Disability. The European Journal of Social and Behavioural Sciences. 18. 2335-2352

- Gavazzi, I. G., & Ornaghi, V. (2011). Emotional state talk and emotion understanding: a training study with preschool children. Journal of Child Language. 38. 1124-1139.

- Graczyk, P., Weissberg, R., Payton, J., Elias, M., Greenberg, M., Zins, J. (2000). Criteria for evaluating the quality of school-based social and emotional learning programs. In R. Bar-On & J. Parker (Eds.), The handbook of emotional intelligence San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. pp 391-410

- Guhur, M. L. (2007). A manifestação da afectividade em sujeitos jovens e adultos com deficiência Mental: Perspectivas de Wallon e Bakhtin. Revista Brasileira de Educação Especial. 13 (3). 381-398.

- Izard, C. E. (2001). Emotional intelligence or adaptative emotions. Emotion, 1, 249-257.

- Ladd, G. W., Birch, S. H., & Buhs, E. S. (1999). Children’s social and scholastic lives in kindergarten: Related spheres of influence? Child Development, 70, pp 1373–1400.

- Ladd, G. W., Herald, S., & Andrews, K. (2006). Young children’s peer relations and social competence. In B. Spodek & O. Saracho (Eds.), Handbook of research on the education of young children. New York, NY: Macmillan. 2, 23-54

- Lewis, M. (2008). The Emergence of Human Emotions. In M. Lewis, J. Haviland-Jones & L. Feldman Barrett (Eds.), The Handbook of Emotions (3rd ed., pp. 332-347). New York: Guilford Press.

- Martins, M. A. (2000). Pré-história da aprendizagem da leitura. Lisboa: ISPA

- Matos, M. (1998). Comunicação, gestão de conflitos na escola. Lisboa: CDI/FMH/UTL. p 75.

- Mayer, J., & Salovey, P. (1999). O que é a inteligência emocional? In P. Salovey & D. Suyter (Eds). Inteligência emocional da criança: Aplicações na educação e no dia-a-dia, pp. 15-49. Rio de Janeiro: Editora Campus Ltd

- Mayer, J., Salovey, P., & Caruso, D. (2000). Models of emotional intelligence. In R. Bar-On & J. Stemberg (Eds.). Handbook of emotional intelligence. Cambridge University Press.396-420

- McClure, K. S., Hapern, J., Wolper, P., & Donahue, J. J. (2009). Emotion Regulation and Intellectual Disability. JoDD- Journal on Developmental Disabilities. Philadelphia. PA.

- Moore, C. D., (2001). Reassessing emotion recognition performance in people with mental retardation: A review. American Journal on Mental Retardation. 106. 481-502.

- Parke, R. (1994). Progress, paradigms and unresolved problems: a complementary on recent advances in our understanding of children´s emotion. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 40,157-169.

- Pereira, C. & Faria, S. (2015). Do you feel what I feel? Emotional development in children with ID. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences. 165 (2015). 52 – 61.

- Saarni, C. (1999). The development of emotional competence. The Guilford Press: New York

- Saarni, C. (2008). The interface of emotional development with social context. In M. Lewis, J. Haviland-Jones & L. Feldman Barrett (Eds.), The Handbook of Emotions (3rd ed., pp. 332-347). New York: Guilford Press.

- Santos, M. (2006). Sentir e Significar. Para uma leitura do papel das narrativas no Desenvolvimento emocional da criança. (Unpublished Doctoral Thesis). Universidade do Mindo. Instituto de Estudos da Criança.

- Santos, M. J. (2002). Todas as Imagens. Coimbra: Quarteto.

- Sim-Sim, I. (2005). Necessidades Educativas Especiais: Dificuldades da criança ou da escola. Lisboa: Texto Editores.

- Sousa, M. E. (2000). Quantos Contos Conto Eu? Malasartes – Cadernos de Leitura para a infância e a Juventude. 3. 21-22.

- Souza, L. O., & Bernardino, A. D. (2011). A contação de histórias como estratégia pedagógica na educação infantil e ensino fundamental. Educere et Educare – Revista de Educação. 6(12). 235-249.

- Thirion-Marissiaux, A. & Nader-Grosbois, N. (2008). Theory of Mind “emotion”, developmental characteristics and social understanding in children and adolescents with intellectual disabilities. Science Direct- research in developmental disabilities. 29. 414-430.

- Tompkins, V., Guo, Y., & Justice, L. M. (2013). Inference generation, story comprehension, and language in the preschool years. Reading and Writing. 26(3). 403-429.

- Traça, M. E. (1992). O Fio da Memória. Do Conto Popular ao Conto para Crianças. Porto. Porto Editora.

- Vale, V. (2009). Do tecer ao remendar: os fios da competência sócio-emocional. Exedra, (2),129-146

- Vale, V. (2012). Tecer para não ter de remendar: O desenvolvimento socioemocional em idade pré-escolar e o programa Anos Incríveis para educadores de infância. (Unpublished Doctoral Thesis). Faculdade de Psicologia e Ciências da Educação da Universidade de Coimbra

- Zins, J., Bloodworth, M., Weissberg, R., Walberg, H. (2004). The Scientific Base Linking Social and Emotional Learning to School Success. Em: Building Academic Success on Social and Emotional Learning: What Does the Research Say? (Eds) Teachers College. Columbia University. 3-22.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

16 October 2017

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-030-3

Publisher

Future Academy

Volume

31

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-1026

Subjects

Education, educational psychology, counselling psychology

Cite this article as:

Faria, S. M. D. M., Esgalhado, G., & Pereira, C. M. G. (2017). Smile, Cry, Scream And Blush – Promoting Socio-Emotional Competences In Children With ID. In Z. Bekirogullari, M. Y. Minas, & R. X. Thambusamy (Eds.), ICEEPSY 2017: Education and Educational Psychology, vol 31. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 719-734). Future Academy. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2017.10.69