Abstract

The purpose of this study was to investigate the potential for an integrated arts therapy intervention to influence youth at risk for delinquent behavior. Toward this goal, we applied a one-group pre-post experimental design to assess the effect of an Integrated Arts Therapy Program on participants’ self-reported life satisfaction, self-esteem (global and academic), mood (general and momentary), and emotional and behavioural problems (emotional, conduct, hyperactivity, peer, and prosocial behavior) in a sample of students with risk of delinquency. Teachers identified at risk youngsters and 95 students aged between 8 and 17 participated in 16 different gender-mixed groups for 16 sessions during eight-week program period. Results of within group comparisons indicated positive, statistically significant improvements from pre- to posttest on all of the measures: (1) increased global self-esteem (the Global Negative Self-Evaluations Scale), academic self-esteem (the Perceived Academic Competence Scale), and life satisfaction (the Students’ Life Satisfaction Scale); (2) decreased total difficulties with conduct and hyperactivity problems, and improved prosocial behavior (the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire); and (3) improved momentary and general mood over time by intervention. These findings indicated that the multi-modal arts therapy group-based program for students with risk for delinquency may be an effective intervention and can lead to at least short-term positive changes by improving participants’ self-esteem, wellbeing and behavioral problems.

Keywords: Integrated arts therapystudents at risk for delinquencyself-esteemwellbeingemotional and behavioral problems

Introduction

Arts and arts therapies can be used by implementing of various modalities of arts (dance, drama, painting, music, painting, photography, sculpture, writing, bibliotherapy, theatres, sand castles) in different contexts – psychotherapy, counselling, rehabilitation or treatment (Malchiodi, 2003). Arts-based programs and arts therapies provide a unique way to help youths, incorporating the arts into treatments for at risk, traumatized, and justice-involved youths (Arts-Based Programs…, 2016), whereby arts therapies focus on the therapeutic relationship and arts-based programs on the process of creating and interpretating of art (Djurichkovic, 2011).

Recent systematic international literature review about the effectiveness of arts therapies with all ages groups was conducted seeking evidence of outcomes for modalities – art, dance-movement, drama, music, and writing (Dunphy, Mullane, & Jacobsson, 2013), whereby any multi-modal (embracing several arts modalities) studies was included. Effectiveness of drama therapy (Kipper & Ritchie, 2003; Wieser, 2007), music therapy (Gold, Voracek, & Wigram, 2004), and dance-movement therapy (Ritter & Graff Low, 1996) have been analyzed by meta-analysis; and effectiveness of art therapy (Reynolds, Nabors, & Quinlan, 2000; Slayton, D’Archer, & Kaplan, 2010) by systematic reviews with all ages of clinical and nonclinical population. A mixed methods systematic review about the effectiveness of arts and arts therapies in offender settings (Meekums & Daniel, 2011) have found generally improved mental health, quality of life and increase of emotional literacy of adult and adolescent offenders.

Problem Statement

During two decades there is a growing body of evidence for the practice and the effectiveness of single- and multi-modal (integrated) arts-based approaches for youngsters at risk and youth involved with the juvenile justice system.

The literature shows that drama therapy is a valuable intervention expanding the possibilities of working with young offenders (Hanna & Hunt, 1999). Drama group therapy intervention’s effectiveness was evaluated through the randomized controlled trial among students at risk for emotional and behavioural problems (McArdle, et al, 2011); and among students with high aggressive behaviour (Karataş & Gökçakan, 2009a; 2009b) showing reduction of behavioural symptoms and total aggression respectively.

There are several studies examining the use of music therapy with young delinquents in detention facilities. In the qualitative research context young offenders have reported benefits of the implication of individual and group-based practices of (popular) music projects with increase of self-expression, self-esteem, impulse control and capacities in the area of social interaction (Rio & Tenney, 2002; Baker & Homan, 2007; Wyatt, 2002). Based on pre-post test experimental studies the Hip-hop and RAP therapy have been cited as effective methods for helping juvenile offenders with behavioral problems (Anderson & Overy, 2010; DeCarlo & Hockman, 2003; Tyson, 2002). Also, randomized controlled study (Johnson, 1981) revealed that involvement in music therapy resulted in significant improvements on measures of self-concept among juvenile delinquents.

Some qualitative (e.g. Goodkind & Miller, 2006; McTaggart, 2010; Oesterreich & McNie Flores, 2009; Mazloomian & Moon, 2007) and mixed methods (Persons, 2009) research showed that individual and group based art therapy programs were beneficial for young offenders in correctional institutions in several ways, with improving of participants’ self-confidence, self-expression, emotional well-being and development of positive interpersonal relationships. Hartz and Thick’s (2005) quasi-experimental study tested the impact of two art therapy approaches on the self-esteem of juvenile offenders and both groups showed a significant improvement in self-esteem. Findings from a one-group pre-post design (Cortina & Fazel, 2015) experimental study revealed that art therapy intervention for students – indicated by teachers as students with risk behavior, had a positive impact on young peoples’ emotional and behavioral problems with reduction of total difficulties and emotional problems, hyperactivity, and problems with peers. Also, this implemented school-based group art therapy program improved selective group students’ mood and feelings. In a randomized controlled trial, participants of group art therapy program were youngsters with aggressive behavior and findings suggested reduction of risk participants’ anger and improvements of their general-, social-, and family self-esteem (Alavinezhada, Marvdas, & Sohrabi, 2014).

The existing literature offers support for the beneficial use of multi-modal arts program applications through individual and collaborative artwork to enhance delinquent youth (Lazzari, Amundson, & Jackson, 2005) and at risk youth (de Roeper & Savelsberg, 2009) emotional and behavioral functioning. Ezell and Levy (2003) conducted a pre-posttest fellow-up study on the evaluation of multi-modal arts-based approaches effects, showing increase of recidivism rates after the three year evaluation for young offenders who were involved in the arts programs during their stay in correctional institution.

The results of three quasi-experimental (Clawson & Coolbaugh 2001; Rapp-Paglicci, Stewart, & Rowe, 2012; Shelton, 2009) studies designed to implement different multi-modal arts-based programs targeting youth with risk for delinquency suggested that programs had positive impacts on yougnster’ attitudes, self-esteem, academic performance and behaviors (including delinquent behaviors) (Clawson and Coolbaugh 2001); self-control, self-esteem, and resilience (Shelton, 2009); and mental health, academic performance and behavior (including internalized and externalizing behaviors) (Rapp-Paglicci et al., 2012). Also, a quasi-experimental evaluation of the single-modal music, drama, and art therapy in educational settings provided evidence of the benefits of the intervention for youth with social, emotional and behavioural difficulties with significant improvements across all measured emotional and behavioral difficulties (emotional problems, conduct problems, hyperactivity, peer problems, and prosocial behavior) one year after implication (Cobbett, 2016).

There are positive attempts – in the qualitative research context, to use the multi-modal arts therapy programs in youth correctional settings (Emerson & Sherlton, 2001), in the context of group counselling of delinquent youth (Mohamad & Mohamad, 2014; Adibah, Marzety, & Zakaria, 2015), and in the group-based play therapy activities with risk adolescents (Perryman et al., 2015).

A quantitative post-group evaluation (Kit & Teo, 2012) research analysis showed that group based multi-modal arts therapy programs were beneficial for offenders and risk-group youth without significant differences between youngsters in these two settings. A quasi-experimental design was applied to evaluate the impact of a multi-modal arts therapy group-based intervention on emotional and behavioural problems of juvenile delinquents in correctional settings and results revealed significant improvements among intervention group youngsters in the area of prosocial behaviour and reduction of conduct and emotional problems, and aggressive behavior (Kõiv & Kaudne, 2015). The practice-based (Smeijsters et al., 2011) research in comprehensive implication of multi-modal arts therapy programs in correctional institutions have found that these interventions can primary serve to reduce impulsiveness, regulate anger, and increase empathy and compliance of young offenders.

Research Questions

Although the evidence base for multi-modal arts approaches is varied in the young offender and risk youth settings – while the majority of the research indicated that arts-based programs and arts therapies were effective at reducing risk group and delinquent youth difficulties, more studies are needed to clarify the potential impacts of multi-modal arts interventions for youth at risk of delinquent behavior. The present research question was evoked: Is the participation in the multi-modal arts therapy intervention program will be beneficial for the students at risk for delinquency?

Purpose of the Study

The aim of the study was to examine the effects of an integrated arts therapy intervention on emotional and behavioural problems, self-esteem, mood, and life satisfaction in a sample of students with risk for delinquent behavior.

It was generally supposed that participation in the multi-modal arts therapy program will be beneficial for youth at risk for delinquency in the area of self-esteem, wellbeing, and behavioural difficulties. Specifically, it was hypothesized that youngsters with risk of delinquency who participate in the integrated arts therapy program (embracing art, drama, music and dance-movement arts modalities) will have higher scores on global self-esteem and general mood, and lower scores on conduct problems at posttest compared with pretest results.

Research Methods

Subjects and research design

A total of 106 mainstream school students from randomly selected eight different schools from one district in Estonia were selected to participate in the study. Teachers were contacted and asked to refer students who demonstrated significant, identifiable emotional and social problems behaviours at schools and had one or more police records during the prior 12 months. Following the teacher’s referral, students’ families returned the consent form with agreement of students’ participation in the program. Participation was in the progam was voluntary, but all decided to participate. However, 11 of these 106 students (10%) were not included as participants due to their dropping out from the program by personal or low motivational reasons. Thus, the whole sample of the study consisted 95 students (48 boys and 47 girls) ranged in age from 8 to 17 years (M = 11.46 years, SD = 1.86), identified as youngsters at risk for delinquency. Data were not collected on other demographic variables or structure of offending for ethical reasons.

A single-group pre-post design was used where participants of the integrated arts therapy program were tested at two time points – a week before and week after the implementing of intervention.

The participants were placed in groups of six to seven students and attempts were made to group participants by age. All formed 16 intervention groups included males and females, running at schools during school year – the first eight groups for eight weeks in the autumn semester, and the second eight groups for eight weeks in the spring semester.

Integrated Arts Therapy Program

For this study, eight-week Integrated Arts Therapy Program was implemented. This program integrated four arts modalities: visual art therapy (about 40%), music therapy (30%), drama therapy (20%), and dance-movement therapy (10%), layering several art modalities in one session and was previously tested (Kõiv & Kaudne, 2015) among juvenile delinquents. The program was designed to follow the school-year schedule and to run as an integrated part of school curriculum with using multi-modal group-based art activities aimed to promote participants’ self-concept, and social and emotional skills. For eight weeks each groups met twice a week, each session lasted 90 min. The program’s total number of sessions was 16 for each group to fit flexibly into the academic semester time frame. The group was conducted by two leaders (second and third author of the study) completed masters’ level education and certified in the area of arts therapies.

Each session follows a uniform structure designed to facilitate group processes within positive youth development framework as non-directive arts therapy work. This structure of sessions was follows: (1) interactive warming up activities; (2) active-improvisational main activities using dance-movement, drama, music, and arts therapy methods around one of the main themes fulfilling the aims of the program; and (3) discussion or sharing.

Measures

Students’ Life Satisfaction Scale (SLSS; Huebner, 1991)

The SLSS is a seven-item self-report measure that has been used with children and adolescents ages 8 to 18. The items require respondents to rate their satisfaction with respect to items that were domain-free (e.g. “My life is better than most kids”). The response format comprised of a 4-point frequency scale, with

Global Negative Self-Evaluations Scale (GSE; Alsaker & Olweus, 1986)

The self-report GSE scale for use with subjects from 10 years of age through adulthood is a six item, 6-point Likert scale, with four of items taken from Rosenberg’s (1965) Self-Esteem Scale. The items were formulated as statements (e.g., “I have often wanted to be someone else” and “I feel quite often that I am a failure”). The response alternatives range from does not apply at all (1)

Perceived Academic Competence Scale (PAC; Alsaker, 1989)

The self-report PAC scale was indicated by a five-item scale on academic self-esteem with example item: “I am able to solve tasks at school quit well”. Participants rated their agreement with each statement on the three-point scale from

Strength and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ; Goodman, 1997)

The self-report SDQ included 25 items in the following 5-item scales: emotional problems, conduct problems, hyperactivity, peer problems, and prosocial behaviour. Each item is scored on a 3-point scale (0 –

Momentary and General Mood Reports

Two six-item self-report questionnaire versions were developed to assess the momentary and general mood of respondents. Subjects were asked to indicate on a 5-point Likert-type scale (1 –

Procedure

One week prior to intervention and one week after students took a paper-and-pencil survey which included: (1) the SLSS; (2) the GSE ; (3) the PAC; (4) the student version of the SDQ; (5) the Momentary and General Mood reports; and (6) additionally, both mood inventory versions after each session during the implementation of the Integrated Arts Therapy Program were reported. All students were informed that their responses would remain confidential and that completion of the survey was completely voluntary. Students participated in all programme sessions and completed all surveys. Missing data were minimal in the completed surveys.

Findings

Pretest and posttest scores of the SSRS, the GSE, the PAC, the SDQ, and the Momentary and General Mood reports scales and corresponding subscales were compared to test for significant differences before and after the program implementation. Because there was one group involved and measured at two times, a paired

The results suggested that the participants global life-satisfaction (measured by the SSRS), global self- esteem (measured by the GSE), and the academic self-esteem (measured by the PAC) increased after intervention, whereby the results between the pre- and posttest were statistically significant.

The total rates of the SDQ results showed a significant difference in improvement of levels of participants’ difficulties compared to the pretest and posttest results. Three out of five score categories measured by the SDQ showed significant difference in improvement based on the pretest-posttest analysis – namely, decreasing of conduct problems and hyperactivity, and improving of prosocial behaviour. Although there were no statistically significant differences between the pre- and posttest SDQ scores in the area of emotional and peer problems.

The pretest-posttest analysis revealed significant differences in the outcomes connected with mood – students showed a significant reduction in their momentary and general negative mood, and also a significant improvement in their momentary and general positive mood (Table

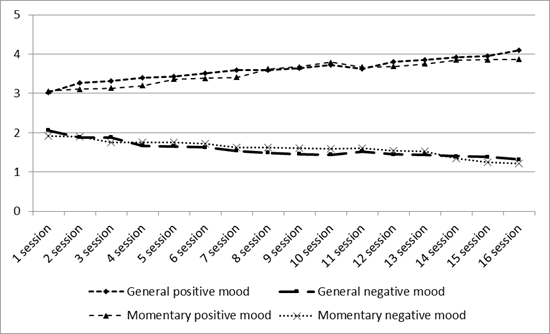

Additionally, momentary and general positive and negative mood was measured across all 16 intervention sessions and results revealed a positive growth tendency in general and momentary mood with decrease of negative mood and increase of positive over time (Figure

Conclusion

Although research that is meant to evaluate arts-based interventions among risk and delinquent youth has undergone growth with promising effects (e.g. Arts-Based Programs…, 2016), an important questions concerning their actual effectiveness are still left open, especially about benefits of multi-modal arts-based approaches for young people with risk of delinquency.

The present research provides initial evidence that youngsters with risk for delinquent behavior are able to benefit from multi-modal (art, drama, music, and dance-movement) arts-based therapy program in school setting. Findings of the present study showed that the Integrated Arts Therapy Program leads to positive self-reported outcomes on risk group youngsters for delinquent behaviour across several key areas: (1) self-esteem (global and academic); (2) global life satisfaction and positive/negative mood (general and momentary); and (3) emotional and behavioral problems (total difficulties with subcategories: conduct, hyperactivity, and prosocial behavior).

It was expected that positive changes on the selected outcome areas – global self-esteem, general mood, conduct problems, would occur for the intervention group members when compared pre- and posttest results. Results supported the hypothesis and revealed that not only supported self-reported variables improved among sample of students with risk for delinquency who participated in the integrated arts therapy program, but also a group of other variables. Namely, it was revealed that there were improvements in global and academic self-esteem, global life satisfaction, momentary and global mood, and reduction of behavioral problems in the area of conduct problems and hyperactivity with improvements of prosocial behaviour among youngsters with risk for delinquency after the implementation of the integrated arts therapy program. Thus, the general prediction that group-based multi-modal arts therapy intervention is beneficial to youth with risk to delinquent behaviour, was approved.

Specifically, the applied integrated arts therapy program was found to have a positive influence on participants’ general self-esteem and on their academic self-esteem compared pre- and posttest results. Several previous evidence-based studies have found improved general self-esteem for justice-involved youth participating in the arts programs (Clawson & Coolbaugh, 2001; Ezell & Levy, 2003; Lazzari et al., 2005; Shelton, 2009); and for juvenile delinquents who have engaged in the art (Hartz & Thick, 2005) and music (Johnson, 1981; Baker & Homan, 200; Rio & Tenney, 2002) therapy programs, whereby art therapy have improved also aggressive youngsters’ general self-esteem (Alavinezhada et al., 2013). These results are parallel with findings supporting the view that adolescents low rather than high self-evaluation is related to offending (Van Damme et al., 2015), with giving an avenue for the justified criticism (Smeijsters, et al., 2011) that focusing only on changing delinquent behavoior is not successful if youngsters self-esteem is not addressed as a target of arts therapy interventions.

Although, studies have provided evidence of the robust negative associations between adolescents academic competence and their delinquent behavior (e.g. Vermeiren et al., 2004), this connection is challenging for implementation of effective arts-based programs and arts therapies for youth. The outcomes of the present study have demonstrated improvements in the academic self-esteem of a sample of students with risk for delinquency who participated in the intervention program, whereby outcomes from previous effective evidence-based arts programs for offenders have revealed improvements in academic performance (Clawson & Coolbaugh, 2001; Rapp-Paglicci et al., 2012).

Secondly, it was reviled that youngsters at risk for delinquency receiving multi-arts approach as the group intervention exhibited improvement in their wellbeing connected with two aspects: general life satisfaction and general/momentary affective states.

Among various aspects of well-being, global life satisfaction is most widely used as a correlate or indicator of delinquent behavior in adolescents (e.g. Sun & Shek, 2010), with specification (Jung & Choi, 2017) that high levels of life satisfaction is viewed as a protective factor against delinquent behaviors among adolescents. Therefore the positive results of present study in the area of increasing life satisfaction among youths with risk for delinquency may provide a preliminary support for the application of the integrated arts therapy as an effective mean for prevention of juvenile offending.

At the other side, present results from a range of inventories measuring general and momentary mood administered before and after the eight-week intervention, and also across all intervention sessions, indicated that the integrated arts therapy program had positive impact on the participants’ mood. These results are consistent with previous indicating that art therapy (Goodkind & Miller, 2006; Persons, 2009), music therapy (Baker & Homan, 2007), arts therapies (Adibah et al., 2015; McMackin et al., 2002; Mohamad & Mohamad, 2014), and arts-based programs (Ezell & Levy, 2003) for juvenile delinquents and for youngsters of risk of delinquency (Cortina & Fazel, 2015) can improve the emotional wellbeing of the participants. Nonetheless, the present findings specified results in this area showing that the trend of improvement in the participants’ emotional wellbeing occurred over time by intervention in connection with positive/negative general and momentary mood.

Thirdly, results of this study suggested that the integrated arts therapy program was effective in bringing about appropriate behavioral changes among intervention group members with risk for delinquent behavior comparing pre- and posttest results. Namely, the results showed significant reduction in participants’ conduct problems and hyperactivity, and total difficulties, with improvement of procoscial behavior, but the difference for the emotional and peer category was not found to be significant. These results are in the line of several evidence-based prior studies showing that arts-based programs were effective to reduce risk group youngsters delinquent behavior (Clawson & Coolbaugh 2001), externalized (and internalized) behaviors (Rapp-Paglicci et al., 2012), and emotional and behavioral problems (measured by the SDQ) (Cobbett, 2016). Also, multi-modal arts therapy was effective to reduce young offenders’ emotional, conduct and aggressive problems with improvement of their prosocial behavior (Kõiv & Kaudne, 2015). In addition, risk group students’ emotional problems, hyperactivity, problems with peers, and total difficulties have improved in relation to the implementation of art therapy interventions. As such, the present arts therapy program and previous arts programs and arts therapies were judged to be fairly successful in reducing the risk-group or delinquent youth behavioral problems, whereby the need for more evidence to connect the arts components of specific interventions to positive outcomes is needed.

The present study suffers some limitations. One of the main limitations is the use of one-group pre-post design and lack of a control group. Further studies should make use of experimental designs where young people are randomly assigned to two groups. The other methodological weaknesses of the study are connected with the short follow-up periods, and reliance on only self-report measures.

However, findings of the present research demonstrate that targeted intervention – the integrated arts therapies program for youngsters of risk of delinquency, might be effective preventive approach for youngsters’ delinquent behavior and can lead to at least short-term positive changes by improving participants’ self-esteem and wellbeing in combination with appropriate behavioral changes.

References

- Arts-based programs and arts therapies for at-risk, justice-involved, and traumatized youths: Literature review. (2016). Washington, D.C.: Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention. Retrieved from https://www.ojjdp.gov/mpg/litreviews/Arts-Based-Programs-for-Youth.pdf.

- Adibah, M., & Zakaria, M. (2015). The efficacy of expressive arts therapy in the creation of catharsis in counselling. Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences, 6(6), 298–306.

- Alsaker, F. D. (1989). School achievement, perceived academic competence and global self-esteem. School Psychology International, 10, 147–158.

- Alsaker, F. D., & Olweus, D. (1986). Assessment of global negative self-evaluations and perceived stability of self in Norwegian preadolescents and adolescents. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 6, 269–278.

- Alavinezhada, R., Marvdas, M., & Sohrabi, N. (2014). Effects of art therapy on anger and self-esteem in aggressive children. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 113, 111–117.

- Anderson, K., & Overy, K. (2010). Engaging Scottish young offenders in education through music and art. International Journal of Community Music, 3(1), 47–64.

- Baker, S., & Homan, S. (2007). RAP, recidivism, and the creative self: A popular music programme for young offenders in detention. Journal of Youth Studies, 10(4), 459–476.

- Clawson, H. J., & Coolbaugh, K. (2001). The Youth ARTS Development Project. Juvenile Justice Bulletin. Washington, DC: Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention, US Department of Justice.

- Cobbett, S. (2016) Reaching the hard to reach: Quantitative and qualitative evaluation of school-based arts therapies with young people with social, emotional and behavioural difficulties, Emotional and Behavioural Difficulties, 21(4), 403–415.

- Cortina, M., & Fazel, M. (2015). The Art Room: An evaluation of a targeted school-based group intervention for students with emotional and behavioural difficulties. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 42, 35–40.

- DeCarlo, A., & Hockman, E. (2012). RAP Therapy: A group work intervention method for urban adolescents. Social Work with Groups, 26, 45–59.

- de Roeper, J., & Savelsberg, H. J. (2009). Challenging the youth policy imperative: Engaging young people through the arts. Journal of Youth Studies, 12(2), 209–225.

- Djurichkovic, A. (2011). Art in prisons: A literature review of the philosophies and impacts of visual arts programs for correctional populations. Salisbury East, QLD: Arts Access Australia.

- Dunphy, K., Mullane, S., & Jacobsson, M. (2013). The effectiveness of expressive arts therapies. A review of the literature. Melbourne: PACFA.

- Emerson, E., & Shelton, D. (2001). Using creative arts to build coping skills to reduce domestic violence in the lives of female juvenile offenders. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 22, 181-195.

- Ezell, M., & Levy, M. (2003). An evaluation of an arts program for incarcerated juvenile offenders. Journal of Correctional Education, 54, 108–114.

- Gold, C., Voracek, M., & Wigram, T. (2004). Effects of music therapy for children and adolescents with psychopathology: A meta-analysis. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 45, 1054–1063.

- Goodkind, S. & Miller, D. L. (2006). A widening of the net of social control? “Gender-specific” treatment for young women in the US juvenile justice system. Journal of Progressive Human Services, 17, 45–70.

- Goodman, R. (1997). The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire: A research note. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 38, 581–586.

- Hanna, F. D., & Hunt, W. P. (1999). Techniques for psychotherapy with defiant, aggressive adolescents. Psychotherapy, 36(1), 56–68.

- Hartz, L. & Thick, L. (2005). Art therapy strategies to raise self-esteem in female juvenile offenders: A comparison of art psychotherapy and art as therapy approaches. Art Therapy, 22, 70–80.

- Huebner, E. S. (1991). Initial development of the Students’ Life Satisfaction Scale. School Psychology International, 12, 231–243.

- Johnson, E. (1981). The role of objective and concrete feedback in self-concept treatment of juvenile delinquents in music therapy. Journal of Music Therapy, 18, 137–147.

- Jung, S., & Choi, E. (2017). Life satisfaction and delinquent behaviors among Korean adolescents. Personality and Individual Differences 104, 104–110.

- Karataş, Z., & Gökçakan, Z. (2009a). The effect of group-based psychodrama therapy on decreasing the level of aggression in adolescents. Türk Psikiyatri Dergisi, 20(4), 1–9.

- Karataş, Z., & Gökçakan, Z. (2009b). A comparative investigation of the effects of cognitive-behavioral group practices and psychodrama on adolescent aggression. Kuram ve Uygulamada Eğitim Bilimleri, 9(3), 1441–1452.

- Kit, P. L, & Teo, L. (2012). Quit Now! A psychoeducational expressive therapy group work approach for at-risk and delinquent adolescent smokers in Singapore, The Journal for Specialists in Group Work, 37(1), 2–28.

- Kipper, D. A., & Ritchie, T. D. (2003). The effectiveness of psychodramatic techniques: A meta-analysis. Group Dynamics: Theory, Research and Practice, 7, 13–25.

- Lazzari, M. M., Amundson, K. A., & Jackson, R. L. (2005). We are more than jailbirds: An arts program for incarcerated young women. Journal of Women & Social Work, 20, 169–185.

- Kõiv, K. & Kaudne, L. (2015). Impact of integrated arts therapy: An intervention program for young female offenders in correctional institution, Psychology, 6, 1–9.

- Malchiodi, C. A. (2003). Expressive arts therapy and multimodal approaches. In C. A. Malchiodi (Ed.), Handbook of art therapy (pp. 106–119). New York and London: The Guilford Press.

- Mazloomian, H., & Moon, B. L. (2007). Images from purgatory: Art therapy with male adolescent sexual abusers. Art Therapy. Journal of the American Art Therapy Association, 24(1), 16–21.

- McArdle, P., Young, R., Quibell, T., Moseley, D., Johnson, R., & LeCouteur, A. (2011). Early intervention for at risk children: 3-year follow-up. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 20(3), 111–120.

- McTaggart, K. (2010). Art therapy and young offenders. Journal of Thai Traditional & Alternative Medicine, 8, 69–75.

- Meekums, B., & Daniel, J. (2011). Arts with offenders: A literature synthesis. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 38, 229–238.

- Mohamad, S. M. A. A. S., & Mohamad, Z. (2014). The use of expressive arts therapy in understanding psychological issues of juvenile delinquency. Asian Social Science, 10(9), 144–161.

- Oesterreich, H. A., & Flores, S. M. (2009). Learning to C: Visual arts education as strengths based practice in juvenile correctional facilities. Journal of Correctional Education, 60(2), 146–162.

- Perryman, K. L., Moss, R., & Cochran, K. (2015). Child-centered expressive arts and play therapy: School groups for at-risk adolescent girls. International Journal of Play Therapy, 24(4), 205–220.

- Persons, R. W. (2009). Art therapy with serious juvenile offenders: A phenomenological analysis. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, 54, 433–453.

- Rapp-Paglicci, L.A., Stewart, C., & Rowe, W. (2012). Improving outcomes for at-risk youth: Findings from the prodigy cultural arts program. Journal of Evidence-based Social Work, 9, 512–523.

- Reynolds, M. W., Nabors, L., & Quinlan, A. (2000).The effectiveness of art therapy: Does it work? Art Therapy, 17(3), 207–213.

- Rio, R. E., & Tenney, K. S. (2002). Music therapy for juvenile offenders in residential treatment. Music Therapy Perspectives, 20, 89–97.

- Ritter, M., & Graff Low, K. (1996). Effects of dance/movement therapy: A metaanalysis. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 23, 249–260.

- Rosenberg, M. (1965). Society and the adolescent self-image. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- SDQ (Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire) (2001). What Is the SDQ? Retrieved from http://www.sdqinfo.com/b1.html.

- Shelton, D. (2009). Leadership, education, achievement, and development: A nursing intervention for prevention of youthful offending behavior. Journal of the American Psychiatric Nurses Association, 14(6), 429–441.

- Slayton, S., D’Archer, J., & Kaplan, F. (2010). Outcome studies on the efficacy of art therapy: A review of findings. Art Therapy: Journal of the American Art Therapy Association, 27(3), 108–118.

- Smeijsters, H., Kil, J., Kurstjens, H., Welten, J., & Willemars, G. (2011). Arts therapies for young offenders in secure care: A practice based-research. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 38, 41–51.

- Sun, R. C. F., & Shek, D. T. L. (2010). Life satisfaction, positive youth development, and problem behavior among Chinese adolescents in Hong Kong. Social Indicators Research, 95, 455–474.

- Tyson, E. H. (2002). Hip-Hop therapy: An exploratory study of a rap music intervention with at-risk and delinquent youth. Journal of Poetry Therapy, 15, 131-144.

- Van Damme, L., Colins, O., & Pauwels, L. J. R., Vanderplasschen, W. (2015). Relationships between global and domain-specific self-evaluations and types of offending in community boys and girls. Journal of Community Psychology, 43(8), 986–1004.

- Wieser, M. (2007). Studies on treatment effects of psychodrama therapy. In C. Baim, J. Burmeister, & M. Maciel (Eds.), Psychodrama: Advances in theory and practice (pp. 271–292). London: Routledge.

- Wyatt, J. G. (2002). From the field: Clinical resources for music therapy with juvenile offenders. Music Therapy Perspectives, 20, 80–88.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

16 October 2017

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-030-3

Publisher

Future Academy

Volume

31

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-1026

Subjects

Education, educational psychology, counselling psychology

Cite this article as:

Kõiv, K., Hannus, R., & Kaudne, L. (2017). Effects Of Integrated Arts Therapy Intervention In Youngsters At Risk For Delinquency. In Z. Bekirogullari, M. Y. Minas, & R. X. Thambusamy (Eds.), ICEEPSY 2017: Education and Educational Psychology, vol 31. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 17-28). Future Academy. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2017.10.3