Abstract

The use of information and communication technologies in education at all types of schools is becoming commonplace nowadays. The generally declared need for the integration of new media and educational technologies in the educational process could represent an important impulse for the development of pedagogical sciences. Some of the modern forms of study in both Czech and foreign schools are altogether based on the use of information and communication technologies. These facts encourage places new demands on teachers who have to be prepared to work with modern ICT and at the same time create appropriate educational materials for such tuition. As a result of this fact, it is necessary to promote new educational techniques and methods derived from them and thus there arises a question whether schools, teachers and teachers-to-be are ready for such a thing.

Keywords: Educational processICT toolsICT tools supported teaching

Introduction

It is not necessary to persuade anybody about the fact that the ICT tools (ICT tools - meaning technical devices, e.g. interactive boards, tablets, computers, etc., but also educational software, educational websites, e-learning portals, electronic educational materials, e-books, etc.) develop progressively. It is also not necessary to ask the generation of sixty- and seventy-year-olds about the information technologies at their school desks. If we ask the generation of today’s fifty-year-olds, they will probably remember calculators; however, the majority will say that they had not come across this type of technology at basic school directly, that they had only heard that there is a thing called computer (or other technologies). If we ask the generation of today’s forty-year-olds and if they remember their years at desks, they will immediately cross their minds a revolutionary novelty – a computer. They will probably also remember a number 386 with a floppy disc drive. Analyzing the content for information science’s lessons 20 years ago, we will recall mainly the following topics: “how to turn on a PC”, “why and when is the restart used”, and “how to insert a floppy disc into a drive and how to display the files or how to start a game”. Then, we also remember a topic “the Internet” which was (in the first grade of secondary school) the main ICT topic. If we look at school’s ICT topics today, we discover that topics which we have learnt 15 years ago are not learnt any more (since every pupil already knows that), and the topics to be learnt by today’s pupils seem to our parents too professional.

ICT tools (or information and communication technologies – often called digital technology) also influenced the recipients of education – pupils – as a result of its penetration into all spheres of life. The idea of natural use of ICT – i.e. modern social networks and open information sources – by the contemporary generation of pupils and students starts to be gradually seen as a fact which is based on the two main arguments. The first is based on the fact that today’s children and students handles and controls the computer technology with a matter of astounding course. The second argument is based on the stats of ICT use according to the age – they show that, unlike the older generations, almost all children use the Internet and a computer (Lupač, 2011). These two arguments provided a base for ideas of the American author Don Tapscott (1998, pp. 22–27) while he called the power model of a family distorted since it is children who teach their parents to orientate themselves in a digital environment now. Its terms N-GEN and

Problem Statement

In the Czech Republic, the school ICT level is monitored from the constitution of National Information Policy in Education (in Czech:

In the connection of publishing and research activities related to the issue of the employment and application of information and communication technologies in education based on the implementation of the concept of connectivist learning theory, it is possible to observe three major thought schools.

The first and the oldest one focuses on the use of learning networks in education. It primarily deals with the topics related to ICT tools in the narrow sense of the word that is to say in connection with distance education with a minimum attendance of learners in classes. There exist many studies dealing both theoretically and empirically with the problem, e.g. Zounek (2009a, 2009b), Clark and Mayer (2008), Paulsen, (2003), Barešová (2003), Eger (2002), Kopecký (2006), Průcha and Mika (2000), etc.

The second thought stream focuses on issues related to ICT tools in a wider sense comprising new topics such as dealing with the possible uses of MOOC (Massive Open Online Course) and social networks (Web 2.0) in education. Compared to the first stream, more general issues and principles connected with possible distribution of educational content and communication via ICT tools, and also with the appropriate structuring of learning materials and the impact of communication on the process are dealt with. This area has also been described by a number of authors, e.g. Matt and Fernandez (2013), C. Parr (2012), Kop (2011), Iiyoshi and Vijay (2008), Li and Powell (2013), Zounek and Sudický (2012), etc.

The third thought and research stream focuses on the competences of pupils and students with respect to the employment of advanced ICT tools. This area focuses on the definition and the exploration of competences that pupils and students have or which they need to develop in order to be able to use all the possibilities offered by modern ICT. There have been numerous research plans and projects in this area; however, one of them dominates. It is the currently implemented international research project ICILS (International Computer and Information Literacy Study) involving the total of 18 countries from all around the world. This international project aims at gaining insight into pupils’ skills regarding computer and information literacy, which a wide range of other, similarly targeted researches and information resources, both of domestic and foreign provenience, have focused on as well.

Research Questions

This only illustrates how wide the range of topics connected with the use of ICT tools at schools is. However, within the framework of our research survey, which shall be presented below, we decided to focus on the topic which is truly regarded as the one being on the front burner (see the above mentioned range of other topical and interesting issues) now. Our research focused on the accessibility of ICT tools to teachers as well as on the needs of the latter with respect to further ICT tools which they would need for their teaching.

The aim of the realized research, which was realized via quantitative research methods, was to find out the responses for the research problems which were stated beforehand. These research problems are described in detail further down in the text and they were based on discovering of the current state of employment of ICT tools in real conditions of pre-primary, basic and secondary schools. In a framework of individual research problems, the facts concerning the frequency and ways of employment of particular ICT tools by teachers were therefore discovered. Furthermore, the ways of possible employment of ICT tools for individual forms of teaching were also discovered, and last but not least the availability of ICT tools for teachers was addressed as well as their demands of particular ICT tools in their teaching. This set of research sub-problems was wholly summarized into the essence of the research problem as follows: Are ICT tools actually available to teachers, and if yes, in what quality and quantity?

Purpose of the Study

The main objective of this paper is to describe the current state of the use of ICT tools in the education process at Czech schools, using the methods of educational research. In addition to the main objective, attention was focused also on determining the specific ways of using these tools under real conditions of the educational process. The paper summarizes selected partial results of a project called “Attitudes of Pupils and Teachers toward Educational Content in the Subject of Informatics at Primary and Secondary Schools“. The main aim of the realized research was, find out how are ICT tools employed, for which teachers’ activities are they employed in the teaching, and is there enough ICT tools at schools.

Research Methods

As a main means for the data collection (necessary for the realization of the research), the questionnaire was used. The questionnaire belongs among indirect – investigational methods – in the structure of research methods classification. The questionnaire can be characterized as a

The constructed research questionnaire was distributed among 850 pedagogical workers of basic and secondary schools. In total, 260 pedagogical workers filled-in the constructed questionnaire, therefore, the response rate was 30.6 per cent which might be a proof that the solved issue is topical and contributing. The research sample consisted of members of teaching staff of 35 schools in total while these schools are based in three regions of the Czech Republic (Olomouc region, Moravian-Silesian region and Zlín region) while 8 of them were respondents from pre-primary schools, 165 respondents were from basic schools, and 81 were based in secondary schools, the rest of 6 respondents expressed their affiliation to “other” type of school. The research sample is described in Table

In order to discover the size of individual groups of respondents (who responded in the same way), basic descriptive statistics were used as well as their visualization via graphs. Additionally, these results were subjected to an analysis while the level of significance of the responses of the individual groups of respondents was studied. These groups of respondents were divided according to their significant characteristics (sex, age, length of professional experience, etc.). In order to perform this verification, we used parametric Student’s t-test which compares the means of one variable in two groups (Chráska & Kočvarová, 2015). We used statistical system Statistica 11 for all calculations and visualizations (Klímek, Stříž & Kasal, 2009).

In the following text, there are some constituent outcomes of realized research, which were based on the finding the current level of employment of ICT tools in real conditions of pre-primary, basic and secondary schools. In the context of the research problems examined, the issues of frequency and ways of use of specific ICT tools by teachers are analyzed, evaluated, and interpreted.

Findings

First analysis presented below was focused on the discovery whether and which ICT tools are available to the members of teaching staff of observed schools. Based on this idea, the following research assumption was created:

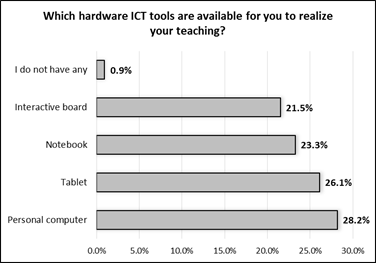

The summarization of responses of the members of teaching staff is presented in Figure number 01 below. Based on this graph, it was possible to perform the verification of the stated research assumption.

As it can be concluded from the stated Figure

An interesting fact is that a large group of respondents stated that they had a tablet which is available for them, however, this device occurred only in small numbers in previous analyses (employment of ICT tools in order to prepare teaching materials, realize frontal or individualized teaching). This fact was probably caused by a fact that the tablets are devices used to “consume” the content, not to “create” content – this may dissuade the members of teaching staff from their employment in real teaching conditions. Therefore, they tend to choose such tools which enable the creation of content (e.g. a personal computer, a notebook, an interactive board, etc.)

Based on this fact, it is therefore possible to accept the stated research assumption and to specify it while stating that to the members of school teaching staff, the necessary hardware ICT tools are available while the most common tools are: personal computers (28.2 per cent), notebooks (23.3 per cent), tablets (26.1 per cent), and interactive boards (21.5 per cent).

Teachers' attitudes towards the availability of software ICT tools at schools

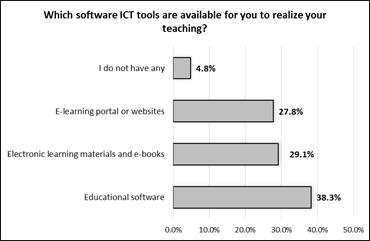

The aim of this analysis was to discover whether and which software ICT tools are available to the members of teaching staff of the observed schools. Therefore, it reacted on the fact that a mere availability of hardware ICT tool does not imply the possibility of its purposeful employment in the teaching (with an exception of a hardware ICT tool itself being an object of teaching, e.g. teaching of ICT tools) – it is necessary to own a corresponding learning material in a form of educational software, or electronic learning material. Based on this idea, the following research assumption was created:

The summarization of responses of the members of teaching staff is presented in Figure number 02 below. Based on this graph, it was possible to perform the verification of the stated research assumption.

As it can be concluded from the stated Figure

Based on this fact, it is therefore possible to accept the stated research assumption and to specify it while stating that to the members of school teaching staff, the necessary software ICT tools are available while the most common tools are: educational software (38.3 per cent), electronic learning materials (29.1 per cent), and e-learning portals or websites (27.8 per cent).

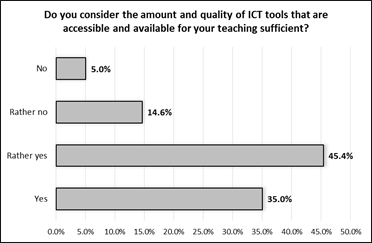

Teachers' attitudes to the total amount and quality of available ICT tools

The previous analyses resulted in a conclusion that the employment of ICT tools (both software and hardware) is frequent while the most members of teaching staff create and modify the necessary electronic learning materials themselves and that they have a sufficient amount of them. In this connection, we were also interested in the perception of the members of teaching staff of the overall amount and quality of ICT tools available. Based on this idea, the following research assumption was created:

The summarization of responses of the members of teaching staff is presented in Figure number 03 below. Based on this graph, it was possible to perform the verification of the stated research assumption.

As it can be concluded from the stated Figure

The discovered results were subjected to further analyses which were focused on the fact whether there are independent on individual significant characteristics of the groups of respondents. Based on this, there were the following research hypotheses stated (a hypothesis was formulated for each significant characteristic, afterwards a related null and alternative hypotheses were formulated as well).

H1: The members of teaching staff – males – consider the amount and quality of ICT tools

H2: The members of teaching staff with a longer professional experience consider the amount and quality of ICT tools available to them more sufficient than the members of teaching staff with a shorter professional experience.

H3: The members of teaching staff of secondary schools consider the amount and quality of ICT tools available to them more sufficient than the members of teaching staff of pre-primary and basic schools.

H4: The members of teaching staff of schools with a higher number of pupils consider the amount and quality of ICT tools available to them more sufficient than the members of teaching staff of schools with a lower number of pupils.

The stated hypotheses were verified on a sample of 260 respondents via Student’s t-test for independent groups while significant characteristics of the group of respondents were a grouping variable, as presented in Table number

In the case of testing the dependence on sex, a value of p = 0.177746 was reached. Based on these results, we cannot refuse the null hypothesis, therefore, it is possible assume (with a lot of probability) that

Conclusion

Nevertheless, it is possible to state that the group of the members of teaching staff with the length of professional experience of less than 10 years showed surprisingly lower frequencies in some analyses than the group of the members of teaching staff with the length of professional experience of more than 10 years. Despite the fact that these results were not (usually) statistically significant, it is necessary to think about this fact. One possible explanation may be the fact that this group of the members of teaching staff perceive the employment of ICT tools in their teaching as natural part of the teaching – therefore they do not perceive even their employment as something “new”.

The fact that these members of teaching staff went through their pre-gradual training in times when the ICT tools and their employment in the educational process were already a part of their training might be strengthened in favor of this conclusion. Therefore, the ICT tools and their employment seem natural for them. However, it is also possible to consider the whole issue from a different perspective related to the teaching experience. In this perspective, it is possible to state that the members of teaching staff with a shorter length of professional experience need more time and energy to manage pupils and organization of their teaching – therefore they do not have neither time nor energy for a more frequent employment of ICT tools. It is, of course, merely a contemplation which should be supported by a relevant statistical analysis which is, however, a direction in which we want to take in the future in order to create an additional research work of this field.

In the framework of the realized research, whose main outcomes are presented above, we managed to identify albeit a small group of the members of teaching staff, it was however a group whose members declared (in their responses) a lower frequency of ICT tools employment and also a lower level of their assessed applicability.

However, the above-stated outcomes also show that at least in terms of hardware and software equipment, as well as the number of electronic learning materials, our schools are not as bad off as they are sometimes referred to. A total of 80.4% of teachers are satisfied with the amount and quality of available ICT tools. The question, however, is whether they are actually able and willing to use the ICT tools which they have at their disposal meaningfully and efficiently to support their teaching. In the available literature and official sources it is often reported that the rate of use of ICT tools is lower among Czech teachers than among teachers in other countries (e.g. Zounek, 2009, Brdička, 2010, etc.). The reasons for this situation should therefore be most probably sought elsewhere than in their deficiency. They are indeed more connected with the particular conditions created for teachers in this field and the lack or total absence of methodological support.

Acknowledgments

This article was created with the financial support from the project of the "Grant Fund of the Dean" of the Faculty of Education, Palacký University Olomouc, in the framework of the project entitled "Attitudes of Pupils and Teachers toward Educational Content in the Subject of Informatics at Primary and Secondary Schools". The project was realized in 2017.

References

- Barešová, A. (2003). E-learning ve vzdělávání dospělých. Praha: VOX. 110 p.

- Bennett, S., Maton, K. & Kervin, L. (2008). The ‘digital natives’ debate: A critical review of the evidence. British Journal of Educational Technology 39(5), pp. 12–31.

- Brdička, B. (2009). Jak učit ve všudypřítomném mraku informací? P. Sojka, J. Rambousek (eds.), SCO 2009, sborník 6. ročníku konference o elektronické podpoře výuky. Brno: Masarykova univerzita, pp. 22–34.

- Clark, R. C. & Mayer, R. E. (2008). E-learning and the science of instruction: proven guidelines for consumers and designers of multimedia learning. San Francisco: Pfeiffer. 510 p.

- Eger, L. (2002). Příprava tutorů pro distanční výuku s využitím on-line formy studia. Plzeň: ZČU.

- Gavora, P. (2010). Úvod do pedagogického výzkumu. Brno: Paido. 261 p.

- Chráska, M. & Kočvarová, I. (2015). Kvantitativní metody sběru dat v pedagogických výzkumech. Zlín: Univerzita Tomáše Bati ve Zlíně, Fakulta humanitních studií. 132 p.

- Iiyoshi, T. & Vijay, M. S. (2008). Opening Up Education: The Collective Advancement of Education through Open Technology, Open Content, and Open Knowledge. Chicago, M.I.T. Press. 265 p.

- Jonnasen, D. H. (2003). Learning to Solve Problems with technology: A Constructivist Perspective. New Jersey: Merill Prentice Hall.

- Klement, M. (2015). Způsoby rozvoje kompetencí učitelů v oblasti práce s moderními didaktickými prostředky. Trends in Education 8(1), pp. 193–201.

- Klímek, P., Stříž, P. & Kasal, R. (2009). Počítačové zpracování dat v programu STATISTICA. Bučovice: Martin Stříž. 102 p.

- Kop, R. (2011). The challenges to connectivist learning on open online networks: Learning experiences during a massive open online course. International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning, 12(3). Athabasca, AU Press.

- Kopecký, K. (2006). E-learning (nejen) pro pedagogy. Olomouc: Hanex. 121 p.

- Li, Y. & Powell, S. (2013). MOOCs and Open Education: Implications for Higher Education White Paper. University of Bolton: CETIS, 2013. 117 p.

- Lupač, P. (2011). Mýty (a realita) digitální generace [online]. Lupa, 2011 [cit. 2016-01-10]. Avaible at: http://www.lupa.cz/clanky/myty-a-realita-digitalni-generace/

- Matt, S. & Fernandez, L. (2013). Before MOOCs, Colleges of the Air. Chronicle of Higher Education, 40(2). Washington D.C.

- Palfrey, J. & Glasser, U. (2008). Born Digital: Understanding the First Generation of Digital Natives. Oxford, Oxford Press.

- Parr, Ch. (2012). "Mooc creators criticise courses’ lack of creativity". Times Higher Education, 10(4). London, TSL Education.

- Paulsen, M. F. (2003). Online Education and Learning Management Systems - Global Elearning in a Scandinavian Perspective. Oslo: NKI Forlaget. 337 p.

- Prensky, M. (2001). Digital Natives, Digital Immigrants: Do They Really Think Differently? On the Horizon 12(2), pp. 7–11.

- Prensky, M. (2009). H. Sapiens Digital: From Digital Immigrants and Digital Natives to Digital Wisdom. Innovate 13(2), pp. 45–61.

- Průcha, J., Walterová, E., & Mareš, J. (2005). Pedagogický slovník. 3. eds. Praha: Portál Vydavatelství, 284 p.

- Survey of Schools: ICT in Education Benchmarking Access, Use and Attitudes to Technology in Europe’s Schools. 2013. [cit. 2016-5-25]. Avaible at: https://ec.europa.eu/digital-agenda/sites/digital-agenda/files/KK-31-13-401-EN-N.pdf.

- Šimonová, I. (2010). Styly učení v aplikacích eLearningu. Hradec Králové: M&V.

- Tapscott, D. (1998). Growing Up Digital: The Rise of the Net Generation. New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Veen, W. & Vrakking, B. (2006). Homo Zappiens. Growing Up In A Digital Age. London, Network Continnum Education.

- Zounek, J. & Sudický, P. (2012). E-learning učení se s online technologiemi. Praha, Wolters Kluwer. 248 p.

- Zounek, J. & Šeďová, K. (2009). Učitelé a technologie: mezi tradičním a moderním pojetím. Brno: Paido.

- Zounek, J. (2009a). E-learning – jedna z podob učení v moderní společnosti. Brno: Masarykova univerzita. 161 p.

- Zounek, J. (2009b). E-learning ve školním vzdělávání. In Průcha, J. a kol. Pedagogická encyklopedie. Praha: Portál, pp. 277 – 281.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

16 October 2017

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-030-3

Publisher

Future Academy

Volume

31

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-1026

Subjects

Education, educational psychology, counselling psychology

Cite this article as:

Klement, M. (2017). Which ICT Tools Are Used By Teachers Most Often In Their Work?. In Z. Bekirogullari, M. Y. Minas, & R. X. Thambusamy (Eds.), ICEEPSY 2017: Education and Educational Psychology, vol 31. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 252-263). Future Academy. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2017.10.24