Abstract

The article analyses the role and meaning of phraseological units in oral practice of journalists in the aspect of modern education in media. Due to informatization the issue of study process in modern knowledge is stated, especially in language education. Text here becomes a verbal message to public. The article deals with the features of understanding and use of special speech units - phraseological units, objective regularities of the correlation of factors contributing to the emergence of phraseological meanings, SPU classes (somatic phraseological units), reveals a key component in them - a grammatically controlled word that forms a metaphorical meaning and is its semantic centre. The use of phraseological units in the speech of a journalist contributes to the development of a language flair, which is especially necessary for the professional activity of a journalist in the conditions of new challenges of the modern information age. Phraseological units as special speech units occupy a special place in modern media practice, and knowledge of their key supporting structural components allows the journalist to correctly and adequately fulfill his professional duties in transferring, reflecting and covering information contained in the media message. The article proposes a universal way to identify the semantic key in phraseology that will help the journalist to master, correctly perceive a linguistic unit and accurately convey its meaning to a mass audience.

Keywords: Media educationmedia practicejournalismspeech unitsomatic phraseological unitsdominant word

Introduction

The information age contributes to the fact that for the journalist all the information space is transformed into an educational space. Expansion of the segment of spontaneous, unprepared journalistic practice leads to the fact that the journalist constantly participates in press conferences, briefings, highlights meetings and appearances of media people of different levels, up to the highest. The media discourse of these people is saturated with figurative language means, including phraseological units that reflect the essence of the author's media message. The journalist's media discourse is also rich in such types of speech units. Consequently, the task of modern journalistic education is to enable the journalist to understand and use special speech units. Moreover, the modern development of the global information space is accompanied by a constant acceleration of information flows and media exchange of information while intensifying the processes of mass communication.

As humanity enters post-industrial era, the specificity of education also changes. Due to informatization an issue of study process in modern knowledge is stated, especially in language education. By the end of the 20th century a new scientific direction appears – medialinguistics, which means a systematic complex approach to the study of media language. Corner, a British scientist, highlights interdisciplinary character of the new theory, uniting a wide sector of research related to such fast developing scientific area as the language of media (Corner, 1996). We cannot defile real language processes related to new informational technologies, but with new characteristics our parole “doesn’t become computerized or Internetized, it’s still our, human parole” (Trophimova, 2009). That’s why we find analysis of phraseological units as a specific lexical layer, which allows us to study peculiarities of a people’s mentality, to be quite topical.

We are speaking about the aspect of culture which is related to the study of media texts, especially to the relations of culture and language, and we regard language as the most important factor of national culture. Levi-Stross, K. justifies the idea: “Language is a factor of culture mainly because language is an indispensible part of culture, besides language is the main means to learn culture” (Dobrosklonskaya, (2008).

The same idea is developed by Kramasch, saying that language plays a major role not only in creating culture but in the appearance of new cultural changes (Kramasch, 2008).

Research Questions

One of the pressing matters of modern education in media is understanding of meaning of a text written by a journalist in any given variety of interpretation. One of the main functions of mass media is to provide communication. Text here becomes a verbal mediamessage to public, its meaning should be open and clear to be persuasive. That’s why it becomes very important to provide for an adequate communication means between transmitting and receiving sides, i.e. an author and his audience. The major input in the development of the theory of media text has been made by such famous scientists as Montgomery, 1992; Martinet, 1969; Van Dijk, Teun, 1998; Fowler, 1991; Bell, and others. Bell examined mediatext as a combination of verbal media signs and argued that the definition of mediatext goes beyond the traditional idea of the text as the sequence of words; mediatext reflect the technologies used for their production and dissemination (Bell, 1996). These problems in question became the basis for this research.

Purpose of the Study

The purpose of this article is to prove that is that to use phraseological units in journalist speech proficiently one should develop specific linguistic feeling. The ability to adequately understand, accurately formulate, correctly transmit, and efficiently, timely and appropriately use phraseology is highly desirable for a journalist, since in these special speech units the cultural memory is concentrated and archetypal codes of national mentality are laid down. As, according to Girtler, the manner of formulating and vocabulary is an important sphere in the study of mentality (Girtler, 1995). Such expressions help the journalist laconically, capaciously and figuratively convey to the audience additional meanings that contain appraisal and serve as an expression of the journalist's position or a vivid detail of the speech characterization of the hero of his publication. These are widely used in subjects of publications to provide for a sense of an article, such as “

Research Methods

Study of such issues is based on general approaches in hermeneutics, which studies peculiarities of interpretation of texts, understanding meaning of a statement, essence of communication between journalists and public.

Research basis here was provided by works of such famous philosophers of the 19th century as Gadamer, Hans-Georg, Schleiermacher, Friedrich, Ricœur, Paul, Bachtin, Michail. Gadamer, for example, said, that both text and interpreter belong to and participate in history and language. This “belongingness” to language is the common ground between interpreter and text that makes understanding possible. This phrase is very important in the education of journalists and should make them study language they use in work (Vinogradov, 1986).

Findings

Interpretation of meaning which is in the basis of understanding of journalist text is provided by processes of recoding of meaning while being transmitted from author to audience. This recoding should take into account the need of journalist to create influential textand do this implicitly. As journalist wants not only to transmit information, but also judgmental meanings, he/she inevitably looks for new possibilities to transmit his opinion, hidden in text. These becomes possible by phraseological units, which give Gadamer words on “understanding of speech is not done by summarizing meanings of every word but by following the holistic meaning of spoken” perfect sense (Vinogradov, 1986).

Phraseological units, including somatic ones, are a nationally specific language tool, and therefore their translation by virtue of their uniqueness presents considerable complexity, although according to the notion of the concept of PU (phraseological units) in different languages, there can also be correspondences.

Relying on the theory of this issue, presented both by Russian (Vinogradov, Zhukov, Tesha, Solodub, and others.) (Shelyakin, 2005; Lavrushina, 2012), and by foreign linguists (Fleischer, Girtler, Habermas, - Germany, Ray, Sauvageau, Martine, - France, Moon, Cowie, McKean, McCaig, - Great Britain), let us turn to a comparative analysis of some somatic phraseological units of Russian and German, Russian and English, Russian and French languages.

A phrase from popular speech «gape» (to listen attentively) in German (den Mund auftun) can be used in the sense of "starting to say something, express smth", because the verb auftun (open, unfold) is a neutral variant compared to the verb "gape". Hence a partial lexical inconsistency; PU "through clenched teeth" (with displeasure) also lexically does not quite correspond to the German knurren - grumble, growl; in the Russian language "bite the tongue" means to refrain from unnecessary utterance, in German verstumte rechtzeitig - that is, the translation loses the imagery of the picture; PU "

PU "to have a tooth" (to harbor anger towards someone) - traces from the French avoir une dent, as well as "to have a sharp tongue" (ability to write and talk brightly and fluently, expressively) - avoir la langue acérée (langue effilée). The French expression être (or rester) bouche bée devant qch - to be delighted with something [to be (to remain) gaping in front of someone / something] - is identical to the Russian "open mouth". Also, identical to the Russian phrase, the French expression ne pas oser ouvrir la bouche - do not dare to open (keep silent), which, however, is absent in the Russian analogue ne pas desserrer les dents [do not dare to unclench teeth]. The French expression se mordre la langue - to bite the tongue, is used in the meaning of the previous one and is also identical to the Russian, with the only difference being that there is a return particle se carrying the function of reversing the action on itself. The Russian and other French expressions are identical to the Russian, for example, brailler à plein gosier (shout: to shout at full throat) - to bawl, tear the throat and se rincer le gosier - to wet the throat, that is, to drink alcohol. PU "tinned throat" (About a man capable of loudly singing, screaming, cursing) in French sounds like gosier pavé (a throat lined with a stone). That is, instead of coating with tin, the object is covered with a stone. Apparently, in the language traditions of the French language, the stone is a better protection for the surface than tin.

Phraseological units of the English language show a certain similarity with these of the Russian language. Thus, the expression “hold one's tongue” fully coincides with the Russian one, same with “bite one's tongue off". On the other hand, the expression “a slip of a tongue”, meaning set tongues wagging, does not exactly match the Russian counterparts. In English, phraseological units which are associated with the process of food intake are prominently distinguished, such as “eat away at” - "to destroy something gradually", “eat one's heart out” - "to be very unhappy with something" and ‘bite someone's head off” - "to get angry with someone/something". In Russian language, it is quite difficult to imagine a saying "to bite off someone's head", rather it is to "gnaw through the throat".

As we see, despite certain specific features, there are somatic, lexical, grammatical elements in phraseology, which determine the existence of identical phraseology-somatisms in different languages, which can be explained by universal laws of human thinking, cultural and historical connections of peoples.

It is now common sense, that the phrases, like the sentences, are the units of the language related to the syntax, however, those word combinations in which the totality of their words represent a semantic unity, a semantic integrity, cannot be the object of syntactic study, as “they are so close to vocabulary as compound lexemes, that they should be considered completely independently - in the phraseology section” (Larin, 1977).

We are talking about "indecomposable combinations" (Shakhmatov), "stable combinations" (Abakumov), which represent close unity of several words, expressing a single holistic view. They can be decomposed only etymologically, i.e. outside the system of modern language, historically. This part of the word combinations is separated from the syntax and transferred to the management of lexicology, namely phraseology. Shansky, proposed the following structural categories of phraseological units: speech patterns that are structurally equivalent to the sentence, and units representing a combination of words (Trophimova, 2009).

This is proved by the studies of Western scientists. For example, a British researcher of the theory of phraseology Moon, believes that the main indication of the phraseology of word-combinations is lexical-grammatical stability (Moon, 1998). The authors of the dictionary of English idioms Cowie, McKean, McCaig also say that they study any idiom as the unity of meaning (Cowie, Mackin, McCaig, 2003).

Phraseology is the language unit that is characterized by a content plan, i.e. of a holistic meaning, and a plan of expression-structural separateness (Martinet, 1969).

As part of the phraseological unit (hereinafter – PU), using the method of component analysis, it is possible to isolate the semantic nucleus and subordinate components, the dominant and differential semes (hereinafter – DS).

Phraseological meanings, like lexical ones, can be grouped into broader and narrower classes depending on one or another selected criterion of classification. For the analysis, we have chosen somatic phraseological units (hereinafter referred to as SPU) with somatisms of the mouth, tooth, tongue, throat, mustache.

When the phraseological units with the word “

PU with somatism

The

SPU

The

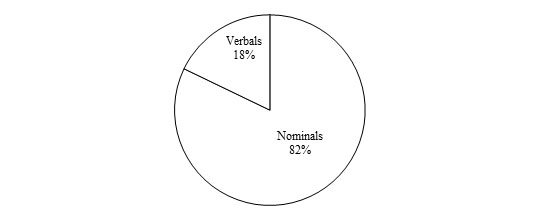

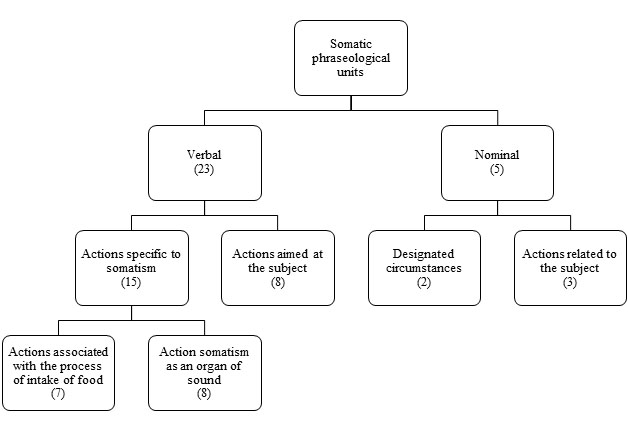

Thus, to confirm the thesis about the predominance of verbal SPU, we propose the following diagrams of somatic phraseological units with somatic

Verbal and nominal SPUs in the quantitative-semantic ratio are distributed as follows (Figure

As we can see, the structure of most SPUs with the somatic component

DS in SPU with somatism

Among the SPU with the word

The

And SPU where action passes to another subject:

The

In the

SPU with the word

The

Very interesting SPU are those in which the value of

The

We should mention among them SPU, which denotes an action that is locked in the subject itself: take (overcome) with the throat; tear one’s throat (pharynx, mouth); piece in the throat gets stuck, cannot push a piece in the throat; shout oneself hoarse; to get a piece not in right throat; wet one’s throat (pharynx); tears came to one’s throat - this is the most numerous group and they are all verbal by structure.

Some SPU are synonymously close in phraseological meaning and differ only in expressively meaningful connotations: take someone by the throat = grab by the throat = step on one's throat; to snatch from one’s throat; to shut up one’s throat (pharynx, mouth), etc. They are all verbal by the grammatical structure. A small number of these are nominal SPU, which denote the circumstances or characteristic of the subject: eat like in three throats, throat of cast iron; full (up to the throat).

SPU with somatism

Two SPUs are interesting here–blow one’s mustache up, or blow one self’s mustache up, they are separated semantically in the sense that the action can be

Per grammatical structure, they all require a verb, though only one nominal SPU defines a characteristical trait:

Discussion

Modern decrease in common literacy and culture of speech covers also area of media. As journalists are more and more engaged in spontaneous and unprepared professional communication, they must rely on high level of knowledge of automated skills of lexical units’ usage and understanding. Common issue here is to misrepresent phraseological units using them not accurately, thus changing their meaning and misleading the audience. That’s why it’s crucial to provide journalists with sufficient luggage of linguistic knowledge related to peculiarities of formation and functioning of phraseological units.

As we see, despite certain specific features, there are somatic, lexical, grammatical elements in phraseology, which determine the existence of identical phraseology-somatisms in different languages, which can be explained by universal laws of human thinking, cultural and historical connections of peoples.

Thus, it can be argued that lexical meanings include phraseological meanings expressed by indecomposable combinations of words. Typically, these values are associated with a rethinking of whole combinations of words in general or with one of the lexical components.

Conclusion

Thus, the study of the peculiarities of the formation of phraseological units is an important part of modern humanitarian media education and professional training of journalists. The analysis has shown that the verbal SPUs are dominant, and their values are associated with a rethinking of whole combinations of words or with an anime from lexical elements. Phraseological units as special speech units that occupy an important place in modern media practice contain the key components, the skill of revealing them allows to adequately, correctly, promptly and accurately cover events, reflect its features and convey the key meanings of media messages.

References

- Bell, A. (1996). Approaches to Media Discourse. London, Blackwell.

- Corner, J. (1996). Documentary Television: The scope for media linguistics. AILA Review, 62–67.

- Cowie ,A., Mackin, R., McCaig, J. (2003). Oxford Dictionary of English Idioms. Oxford, Oxford University Press.

- Dobrosklonskaya, T.G. (2008). Medialigvistika: sistemnyj podhod k izucheniyu yazyka SMI (Sovremennaya anglijskaya mediarech'). Moscow, Flinta-Nauka.

- Fowler, R. (1991). Language in the news: Discourse and ideology in the British press. London, Routledge.

- Gadamer, G.G. (1991). Aktual'nost' prekrasnogo. (Per. s nem.) Moscow, Iskusstvo. [in Rus].

- Girtler, R. (1995). Rondkulturen: Teorie der Unanständigkeit. Wien, Köln, Weimar, Böhlau.

- Kramasch, C. (2008). The Cultural Component of Language Teaching. British Studies Now, 18 January, 4–7.

- Larin, B.A. (1977). Istoriya russkogo yazyka i obshchee yazykoznanie. Izbrannye raboty. Moscow, Prosveshchenie.

- Lavrushina, E.V. (2012). Universal'nye slova i nacional'noe svoeobrazie frazeologii (na materiale proizvedenij I.S. Turgeneva). Moscow, REU name of G.V. Plekhanov.

- Martinet, A. (1969). Le français sans fard Texte. Paris, Presse Universitaire de France.

- Montgomery, M. (1992). An Introduction to Language and Society. London, OUP.

- Moon R. (1998). Fixed Expressions and Idioms in English. A Corpus – Based Approach. Oxford, UK.

- Shanskij, N.M. (2012). Frazeologiya sovremennogo russkogo yazyka: ucheb. posobie. Moscow. Book house «Librokom».

- Shelyakin, M.A. (2005). Yazyk i chelovek: K probleme motivirovannosti yazykovoj sistemy: ucheb. posobie. Moscow, Flinta: Nauka.

- Teun, A., van Dijk.(1998). News as discourse. New Jersey, Hillsdale.

- Trophimova, G.N. (2009). O yazyke, zhanrah i kommunikacii v Runete. Sovremennye tendencii v leksikologii, terminovedenii i teorii LSD.K 80-letiyuV.M. Lejchika:sb. nauch. trudov. Moscow, MGOU, 340–345.

- Vinogradov, V.V. (1986). Ob osnovnyh tipah frazeologicheskih edinic v russkom yazyke. Russkij yazyk. Grammaticheskoe uchenie o slove. Moscow, Vysshaya shkola, 90–162. [in Rus].

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

21 August 2017

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-027-3

Publisher

Future Academy

Volume

28

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-599

Subjects

Education, educational equipment, educational technology, computer-aided learning (CAL), study skills, learning skills, ICT

Cite this article as:

Baryshnikova, E. N., Gotovtceva, A. G., Karpukhina, N. M., & Stroganov, I. A. (2017). Features Of Media Discourse Practices Of Journalists In The Globalizing Information Space. In S. K. Lo (Ed.), Education Environment for the Information Age, vol 28. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 131-140). Future Academy. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2017.08.17