Abstract

Television watching rates are increasing day by day in Turkey and television series are occupying a large part of everyday life in rush. Obviously this brings many problems as undermining reading habits of elementary school students. However, children will continue to be exposed to television series without certain precautions and therefore it is possible to think utilization of the existing television programs in the framework of education. In this connection, in the present study, the most popular historical TV series of recent years in Turkey, “Muhteşem Yüzyıl” (The Magnificent Century), was selected as the sample for the data collection in order to explore the perception of history of elementary school students’. The data collected was analyzed both qualitatively and quantitatively. The findings discussed in relation to the possible educative effects of historical non-educational TV series and movies on students’ perceptions related to history. Thus, this can be a sample step to turn positive many of the negative effects of television.

Keywords: EducationHistoryTV series

1.Introduction

The debates on how the history should be taught and even what "history" really is has continued

for more than a decade. Apart from the issue of whatthe history is, it is clear that the purpose of the

history education should be not only to teach the past incidents but also to provide understanding of the

present time and to offer insights into the future through revealing the phases of human progress (Sungu,

2002). In this regard, in today’s world where rapidly growing technology progresses in various different

fields, not only the history of education, but also all areas of education is clearly reshaped through the

changing technology. In this regard, after Lumiere Brothers held their first screening in 22 December

1895 (Özgüç, 1988) films were started to be produced rapidly and then to be used in education in the first

quarter of the 20th century.

The cinema has created a rich, functional and popular language by combining music, literature,

theater, painting, dancing, acting, and even architecture (İnce Yakar, 2013). Therefore, the cinema has

educational features when even considering just its core structure. Ata (2000) has defined the history

education with the following statement: “History education should include all aspects of social life such

law, morality, language, literature, painting, music, religion, education, etc.” Considering definitions of

the cinema and the history education, it is noteworthy that how much these two definitions made in

different regions at different times fit together and overlap.

Nowadays, in information age, schools and formal education have become indistinguishable from

cultural environment which is heavily influenced by growing technology (Weinstein, 2001). Therefore,

how the history should be taught to students who are raising with advanced audiovisual opportunities has

emerged as a major issue for history educators (Çencen & Demir, 2013).

At this point, in order to concretize the process between past and present and to facilitate to

express abstract concept of the history lessons, historically themed films and television series could be

essential materials for teachers (Çencen & Demir, 2013). Films has also been started to be used for

educational purposes in Turkey since 1990s (Demircioğlu, 2007; Öztaş, 2008). In this regard, various

studies on this issue have indicated that films and television series have strong positive and negative (Bar-

On, Broughton, Buttross, Corrigan, Gedissman, González De Rivas & Hogan, 2001)effects on students’

history perception. Moreover, in order to prevent negative effects of films and series, it is essential to

teach critical thinking skills to students (Stoddard & Marcus, 2010). Because throughout history, political

powers, social groups and media has tried to influence the relationship between the history and

historiography. These influences have led existence of multiple and diverse historiography. Nowadays,

this situation is under the control of the media, especially through television programs such as news,

documentary and discussions. However, it is clear that films and series reach larger numbers of people

than these types of television programs claiming that they address history more objectively (Bilis, 2013).

However, it should be noted that films and series are the fictional products. Because these fictional

products are interpreted through the perceptions of today’s world and the values of popular culture.

Therefore, historical films and series should not take precedence over historical facts and materials.

Instead, they should be used to draw a certain extent of attention to the history in a positive manner. In

today's world, it is impossible to avoid or stay away from such biased programs; therefore, they should be

used for education in an optimum way. On the other hand, how these non-educational films and series

should be used in education should be addressed in different studies.

1.1. Purpose of the study

The aim of the present study is to investigate effects of non-educational television series on

primary school students’ perceptions of the history through The Magnificent Century, the television

series which resounded and caused a lot of debates between 2011 and 2014 in Turkey. Meanwhile,

another aim is to determine the role of non-educational films in education through the case of The

Magnificent Century.

2. Methods

In the present study, a questionnaire developed by researchers was administered in order to

determine effects of series on students’ perceptions of the history. Participants of this study consisted of

primary school students enrolled in fourth grade (n: 150). Data obtained from the questionnaire were

analyzed through SPSS using Chi-Square.

3. Findings

The results showed that there is no significant association between answers of the question and ge

nder (χ2 (1) = 1.972, p > .05). This finding also revealed that boy and girls are equally interested in the

series.

Examining answers of the question “Did you have stronger curiosity and desire to learn other

padishahs’ life after the series came out?” revealed that the number of students who indicated that they

not only watched the series but also have stronger interest in other padishahs’ life is 49 while the number

of students who claimed that they watched it but they did not have more desire to learn other padishahs’

life is 14 (X2=10.434; p<.05). On the other hand, some of students who claimed that they did not watch

the series asserted that their interest in other padishahs’ life has increased after they watched the series.

The essential reason of ambiguousness of this statement resulted from the series’ popularity in Turkey;

therefore, almost all people would have opinions about it even if they did not watch. Because the series

was featured on the media from news to magazine programs and newspaper almost every day. Therefore,

students at the age of 10, who did not watch the series regularly, responded the question as “no” or

“sometimes”. These students also responded “the increment in curiosity” question since they had

opinions about the series although they indicated that they did not watch it. Therefore, after the series

came out, 24 students out of 135 did not have increment in their interest in other padishahs’ life.

There was an association between students asking questions related to the series or discussing

accuracy of the information derived from it in the class and increment of their interest in history lesson (X2=13.320; p<.05). However, findings indicated that many students did not ask questions about this

topic to their teachers and create discussions about it in the class. Moreover, only 24% of the participants’

interest in history lesson did not increase after the series came out. Results also showed that students

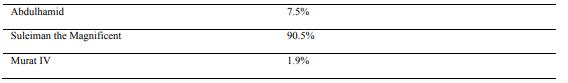

knew more about Suleiman the Magnificent (see Table 4).

4. Conclusions

The studies about learning suggests that students would learn 10 % of what they read, 20 % of

what they hear, 30 % of what they see, 50 % of what they both see and hear, and 90 % of what they both

see, hear, touch and tell (Demirel, 2002; Aktaş, 2015; Özmen, Er & Ünal, 2014). In this regard, the

present study confirms these data that regardless of the gender, all students’ rate of knowing famous

people in the history increases through the characters in the series. Having no gender difference makes

the use of non-educational films and series more functional(Öztaş, Anıl & Kılıç, 2013; Öztaş, 2008).

Findings show that only 24% of 135 participants’ interest in history lesson do not increase after

the series has come out. In parallel to this percentage, analyzing and interpreting the content of history

themed films and series and even including students as one of the largest audience group to these

processes and assisting lessons with films and series could be considered as an effective method to

internalize historical knowledge.

However, present study reveals that after primary school students watch the series, although their

interest in historical issues has increased, they do not bring these issues into classroom to create

discussions and judge the accuracy of what they watch in the films/series. This is one of the major

handicaps in child-media relations. On the other hand, considering the fact that the series increases

interest in the history, it can be claimed that teachers have great responsibilities on this issue. Teachers

should benefit from these positive attitudes and canalize them to the education. Moreover, they should

bring the topic into classroom by using popularity of the series, draw students’ attention to make them

more knowledgeable and challenge them with questions to get students think critically.

Undoubtedly, regardless of age and gender, spending a lot of their time in front of television

without adult control affect students’ academic achievement negatively (Schmidt, & Vandewatert, 2008).

Also it is known the other negative side effects of television (Feshbach, & Singer, 1971). However,

students could choose wisely what they watch if their critical thinking skills and media literacy are

promoted, and they are not exposed harmful effect if they gain self-control (Tesar, & Doppen, 2006). In

this way, non-educational television film and series could be integrated into education (Derelioğlu, & Şar,

2010; Çoban, 2012). Because our findings in parallel to many studies show that films and series, even if

they are produced without educational purposes, have positive educational effects on students. In

particular, students’ higher-order thinking skills which are required in today’s world such as analysis,

synthesis and evaluation can be promoted by such films. Moreover, students can learn about society by

analyzing multifaceted and complex relationships in it (Chansel, 2003).

Films have advantages such as drawing students’ attention, making topics interesting, presenting

concept visually, and making the history interesting and accessible (Kaya & Çengelci, 2011; Savaş, &

Arslan, 2014) . Therefore, teachers can correct biased and misleading aspects of films by using these

features of them to support the lessons. In order to eliminate aforementioned problems, teachers could get

students watch two films having different perspectives on the same topic instead of only one film.

Moreover, teachers could get students watch appropriate parts of films instead of the entire movie. Lastly,

as mentioned earlier, promoting students’ critical thinking skills and media literacy is one of the essential

components of using non-educational films/series in education (Walsh, 2009).

If these essential qualifications are assured, use of films will contribute to effective learning and to

achievement of students not only in history lessons but also in many other lessons.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Istanbul University Scientific Research Projects Coordination Unit. UDP Project number: 39312.

References

- Aktaş, Ö. (2015). 13. Tarih derslerinde yararlanılabilecek savaş filmleri üzerine değerlendirme.

- Dumlupınar Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Dergisi, 43(43).

- Bar-On, M. E., Broughton, D. D., Buttross, S., Corrigan, S., Gedissman, A., González De Rivas, M. R., ...

- & Hogan, M. (2001). Children, adolescents, and television. Pediatrics, 107(2), 423-426.

- Bilis, A. E. (2013). Popüler televizyon dizilerinden muhteşem yüzyıl dizisi örneğinde tarihin

- yapısökümü. İstanbul Üniversitesi İletişim Fakültesi Hakemli Dergisi, (45), 19-38.

- Çencen, N., & Demir, Ö. (2013). Günümüz ortaöğretim 10. sınıf tarih ders kitabı ile muhteşem yüzyıl isimli televizyon dizisindeki" Kanuni Sultan Süleyman dönemi" söylemlerinin göstergebilimsel açıdan karşılaştırılması. Türk Tarih Eğitimi Dergisi, 2(1), 76-101.

- Çoban, S. A. Z. (2012). Tarih derslerinde tarihi film ve dizilerin kullanımına ilişkin öğretmen ve öğrenci görüşleri: trabzon örneği/views of teachers and students on the use of historical films and series in history lessons: the trabzon case. Karadeniz İncelemeleri Dergisi, 13(13).

- Derelioğlu, Y., & Şar, E. (2010). The use of films on history education in primary schools: problems and suggestions. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 9, 2017-2020.

- Demircioğlu, İ.D. (2007). Tarih öğretiminde filmlerin yeri ve önemi. Bilig, 42: 77-93.

- Demirel, Ö. (2002), Planlamadan değerlendirmeyi öğretme sanatı. Ankara. Pegem Akademi.

- Feshbach, S. & Singer, R. D. (1971). Television and aggression. San Francisco. 186-189.

- Kaya, E. & Çengelci, T. (2011). Öğretmen adaylarının sosyal bilgiler eğitiminde filmlerden yararlanılmasına ilişkin görüşleri. Journal of Social Studies Education Research. 2 (1). 116-135. Özgüç, A. (1988). A chronological history of the turkish cinema (1914-1988).

- Özmen, C., Er, H., & Ünal, F. (2014). Televizyon dizilerinin tarih bilinci üzerine etkisi" muhteşem yüzyıl dizisi örneği”/The effect of television series on history awareness “example of magnificient century serıes”. Mustafa Kemal Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü Dergisi, 11(25).

- Öztaş, S., Anıl, N. K., & Kılıç, B. (2013). Tarihi film veya tarihi dizilerinin tarihe ilgiyi artırmada etkisine ilişkin myo öğrencilerinin görüşleri. EJOVOC: Electronic Journal of Vocational Colleges, 3(4). Öztaş, S. (2008). Tarih öğretimi ve filmler. Kastamonu Education Journal, 16, 2: 543-556.

- Savaş, B., & Aslan, Ö. (2014). Tc inkılap tarihi ve atatürkçülük dersinin öğretiminde filmlerin kullanımına ilişkin öğrenci görüşleri. 21. Yüzyılda Eğitim Ve Toplum Eğitim Bilimleri Ve Sosyal Araştırmalar Dergisi, 3(8).

- Schmidt, M. E., & Vandewater, E. A. (2008). Media and attention, cognition, and school achievement. The Future of children, 18(1), 63-85.

- Stoddard, J.D. & Marcus A.S. (2010). More than “showing what happened”: exploring the potential of teaching history with film. The High School Journal, 93 (2): 83-90.

- Sungu, İ. (2002). Tarih öğretimi hakkında, Millî Eğitim Dergisi, Bahri Ata (Çev.) 153/154, 52-59. Tesar, J. E. & Doppen F. H. (2006). Propaganda and collective behavior. The Social Studies. 97 (6): 257-261.

- Walsh, B. (2009). Stories and their sources: the need for historical thinking in an information age, Teaching History,(133), 4-9 .

- Weinstein, P. B. (2001). Movies as the gateway to history: the history and film project. History Teacher, 35 (1): 27.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

25 May 2017

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-022-8

Publisher

Future Academy

Volume

23

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-2032

Subjects

Educational strategies, educational policy, organization of education, management of education, teacher, teacher training

Cite this article as:

İşbilen, E. Ş. (2017). The Perception Of Students’ On History In Non-Educational TV Series. In E. Soare, & C. Langa (Eds.), Education Facing Contemporary World Issues, vol 23. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 552-557). Future Academy. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2017.05.02.67