Abstract

Being studied initially in the field of psychopathology, the

Keywords: Self-oriented perfectionismsocially prescribed perfectionismacademic emotionsacademic achievement

Introduction

Giving the global social interest in performance and excellence, the need to establish high

standards went up in schools. The pupil’s perfectionist propensity is augmented nowadays by some

certain parameters of the educational system: the risen of the school’s quality, the emphasizing of the

social comparison, the salience of self-other evaluations and the preoccupation for self development and

assertion (Rice, Richardson, & Ray, 2016). Pupils are often involved in competitive evaluations which bring out important effects on personal and social standards, on emotions and performances. The

perfectionist personality style is a result of a process of setting excessively high standards because of the

requests and expectations of significant others and based on own previous performances. The aspiration

to perfection is a human ideal intimately bound with the self-actualization need, but when it turn into a

personality trait, beside positive issues, are also coming some negative cognitive and affective products, a

decrease in well-being and in adaptability. In this paper, we analyze perfectionism in connection with

positive and negative academic emotions experienced by high school students, in evaluative contexts.

Perfectionism

In ordinary language perfectionism is associated with positive features of the development and

with performance, but in clinical and personality psychology this construct is connected mainly with

adaptation problems as low self-esteem (Ashby & Rice, 2002), depression and anxiety (Ashby, Rice, &

Martin, 2006; Hewitt et al., 2002) obsessive-compulsive symptoms (Rhéaume, Freeston, Dugas, Letarte,

& Ladouceur, 1995), procrastination (Flett, Blankstein, Hewitt, & Spomenka, 1992; Frost, Marten,

Lahart, & Rosenblate, 1990). Initially the perfectionism have been defined as a single dimension

psychological construct, which describe a person’s tendency to search for perfection, to establish

unrealistically standards, and to be extremely critique with himself and others. Other authors consider that

perfectionism does not imply only negative features. Performance motivation, development and

orderliness desire, tenacious effort trough positive reinforcement being acknowledged (Fedewa, Burns, &

Gomez, 2005). Positive and negative effects of perfectionism may be attributed to the complex,

multidimensional structure of the construct, involving both personal and social aspects, adaptive and

maladaptive characteristics.

Actually, there are three multidimensional conceptualizations of perfectionism that have been most

intensively studied empirically. One of them belongs to Frost et al. (1990) and proposes six dimensions:

high personal standards, concern over mistakes, parental expectations and parental criticism, doubt about

actions, preference for orderliness. Slaney, Rice, Mobley, Trippi, and Ashby (2001) developed another

theory of the perfectionism in three dimensions: personal standards, orderliness, and discrepancy between

performance and standards. Hewitt and Flett (1991) have defined perfectionism as a three dimensions

construct: self-oriented perfectionism (SOP); other-oriented perfectionism (OOP), and socially prescribed

to attain these standards and to avoid failures. OOP is about unrealistic high standard for significant

others, expecting that they will act perfectly and being extremely exigent with them. SPP deal with the

perceived need to attain the standards and the expectations prescribed by other significant persons. The

research performed by Hewitt and Flett (1991) showed that the SOP was highly correlated with high

personal standards, self-criticism, personal performance importance, and personal goals importance. It

was just moderately correlated with anxiety, hostility, and depression. Instead, OOP was positively

associated with other-directed blame, narcissism, social importance goals, authoritarianism and

dominance, but did not correlate with anxiety or depression. SPP was associated with self-criticism,

overgeneralization of failure, self-blame, other-blame, fear of negative evaluation, need for approval of

others, and social goals importance, but was not correlated with high personal standards. SPP was also

linked with some indices of general maladjustment, such as somatic symptoms, depression, anxiety, hostility etc. In relation to perfectionism and its connection with negative emotions, research show that

SOP does significantly correlate with guilt, self-disappointment, and anger, SPP does significantly

correlate with anger, while the OOP was not associated with negative emotions (Hewitt & Flett, 1991).

Generally, research show that SPP is stronger correlated with negative emotional symptoms than the SOP

(Einstein, Lovibond, & Gaston, 2000) and it is a significant predictor for the social anxiety (Cox & Chen,

2015).

Until now, the adaptive and maladaptive perfectionism has been studied in the educational

psychology field mainly in relation to performance and motivation. The positive or negative nature of this

construct has been discussed in rapport with the high standards' feature, like being realistic and able to

motivate or, on the contrary, being unrealistic and undermining the motivation (Rice et al., 2016). High

standards are not incompatible with adaptation unless they are accompanied by exaggerated self-

criticism. Therefore, the perfectionism characterized by realistic high standards has been associated with

successful academic results, while the perfectionism characterized by self-criticism had a variable

association with performance (Accordino, Acordino, & Slaney, 2000). Other studies indicated that SOP

positively predicted mastery goal orientation and SPP positively predicted performance-approach goal

orientation (Damian, Stoeber, Negru, & Băban, 2014). A lot of research does explore the connection of

the perfectionism with different negative emotions, but there is not conclusive data about positive

emotions of pupils in function of the perfectionism.

Academic Emotions

Because of the fact that the educational environment is prevalently evaluative, research has been

focused mainly on test anxiety and much less on the other emotions involved in the cognitive, social and

motivational process regulation (Schutz & Pekrun, 2007). Thus, success enjoyment, pride, hope, but also

shame, frustration, boredom, or hopelessness are examples of emotions involved in school adaptation

process. An important contribution for investigating these emotions is realized by Pekrun and his

collaborators in the framework of

al., 2002). Three categories of emotions related to learning activities and to competence-relevant activities

and outcomes have been identified and named

Maier, 2009; Pekrun et al., 2002). According to the control-value theory, the academic emotions are

generated by some antecedents, like:

self-efficacy expectancy, outcomes expectancy),

(e.g. appreciating an academic activity

task demands) (Pekrun et al., 2007).In their turn, academic emotions have further effects toward

cognitive process, motivation and academic performance. In contrast with former theories that defined

school-related emotions as generalized traits, this approach delineates a specific domain for the affective

reactions. In this new acceptation, causal attribution or the perceived value of the achievement activities

are much more predictive for emotions than student’s personality traits (Pekrun et al., 2007).

Academic emotions were classified according to object focus in two categories:

emotions can be grouped into physiological activating versus deactivating emotions, like hope versus

hopelessness (Pekrun et al., 2011). To assess emotions experienced by the students in various academic

settings, a self-report instrument with 24 scales, named

developed and validated by Pekrun and his colleagues (Pekrun, Goetz, & Perry, 2005; Pekrun et al., 2002;

Pekrun et al., 2011).

Achievement emotions have been already investigated in relation with different motivational

variables and with academic performance. In two studies, Pekrun, Elliot, and Maier (2006, 2009) noticed

the association between academic emotions, achievement goals, and academic performance. Mastery

goals positively predicted enjoyment, hope and pride and negatively predicted boredom, anger, and

hopelessness. Performance-approach goals positively predicted hope and pride, but is unrelated to

enjoyment. Performance-avoidance goals negatively predicted hope and pride and positively predicted

anger, anxiety, hopelessness and shame. Also, academic emotions mediated the link between achievement

goals and performance: hope, pride, boredom, anger, hopelessness, and shame mediated the link between

mastery goals and performance; hope and pride mediated the link between performance-approach goals

and performance; hope, pride, anger, anxiety, hopelessness, and shame mediate the link between

performance-avoidance goals and performance (Pekrun et al., 2006, 2009). Another research indicated

that positive activating emotions like enjoyment, hope and pride were positively correlated with academic

self-efficacy, effort, intrinsic motivation, learning strategies and performance, but the negative

deactivating emotions, like hopelessness and boredom, were negatively correlated. For the negative

activating emotions, like anger or anxiety, the relationships were more complex, these emotions being

negatively correlated with intrinsic motivation, learning strategies, but positively with extrinsic

motivation and achievement outcome (Pekrun et al., 2011).

Purpose and Hypotheses

As reflected by studies, alongside its negative psychopathological associations, in education the

perfectionism is connected with school motivation and achievement (Stoeber & Rambow, 2007), with

achievement goal orientations (Damian et al., 2014), and with positive emotions like hope and pride

(Ashby, Dickinson, Gnilka, & Noble, 2011; Stoeber, Kobori, & Tanno, 2013). In this field, no matter the

psychological instrument used for measurement, two dimensions of perfectionism were considered:

positive vs. negative; adaptive vs. maladaptive. But there are too little research using the

multidimensional model of Hewitt and Flett (1991) in order to analyze perfectionism alongside with

specific academic emotions.

The general purpose of this study is to analyze the relationship between self-oriented and socially

prescribed perfectionism and positive and negative academic emotions related to evaluation context,

taking into account also academic achievement. We removed from our study other-oriented perfectionism

because this dimension was not correlated with emotions in children and adolescents. First, we verified if

there is a correspondence between real and perceived academic achievement. Next, we analyzed the

correlations between perfectionism and academic emotions and investigated the contribution of the self-

oriented and socially prescribed perfectionism in explaining the variation of test-related emotions. Based

on previous researches, we suppose that: 1) Self-oriented perfectionism (SOP) will positively correlate with both positive (hope and pride) and negative test-related emotions (anxiety, anger, and guilt), in

academic achievement control condition; 2) Socially prescribed perfectionism (SPP) will positively

correlate only with negative emotions (anger, anxiety, shame and hopelessness), in academic achievement

control condition.

Participants and Measures

A number of 187 adolescents (age 15.76; SD=.73; range 14-18; 54% females) from two high-

schools in Iasi, Romania, were involved in a paper-and-pencil data collection during classes.

1997) is a multidimensional 22 Likert items scale that measures with two subscales (SOP and SPP)

individual difference in perfectionism in children and adolescents. Self-oriented perfectionism (e.g. „I

want to be the best at everything I do.”) is measured with 12 items and socially prescribed perfectionism

(e.g. „I feel that people ask too much of Me.”) with 10 items. Higher scores on this scale indicate high

levels of perfectionism. Psychometric qualities of the scale have been verified in a few international

investigations (Bento, Pereira, Saraiva, & Macedo, 2014; Hewitt et al., 2002)and in Romanian language

the scale have been translated by two independent translators.

elaborated by Pekrun and colleagues (Pekrun et al., 2005; Pekrun et al., 2002) which measures students’

emotions in three different academic situations: attending class, learning activity, and taking exams or

tests. The instrument is designed to be modular; the three sections of the AEQ and the different emotion

subscales can be used together or separately, according to the needs of the researcher. In this study we

used a short form of the test-related emotions scale:

challenge that is enjoyable.”),

e.g. „I think that I can be proud of my knowledge.”),

exam regardless of outcome.”),

know.”),

ashamed of my poor preparation.”), and

hope that I could do well given topics”). We elaborated and added one more subscale for

e.g. „I feel guilty when I do fail on tests”). Students rate their emotional experiences in three temporal

contexts (before, during and after examinations) on a seven point Likert scale. Higher scores on this scale

indicate high levels of the intensity of emotions.

semester in all subject areas.

perception onto their own academic outcomes: „If you were to appreciate your school outcomes on a

scale with 10 levels, where do you think is your place,

Results

All the subscales had a good internal consistency (Tabel 1). There are no discrepancies between

real (AA) and perceived academic achievement (PAA), as correspondence analysis and correlation coefficient (.74) denote. Bivariate correlation analysis showed that there is a significant correlation (.68)

between the two types of perfectionism. Self-oriented perfectionism correlated positively with each

positive and negative test-related emotion, except hopelessness and also with academic achievement.

Socially prescribed perfectionism does positively correlate with each positive and negative test-related

emotion, but it does not significantly correlate with relief after tests (Table

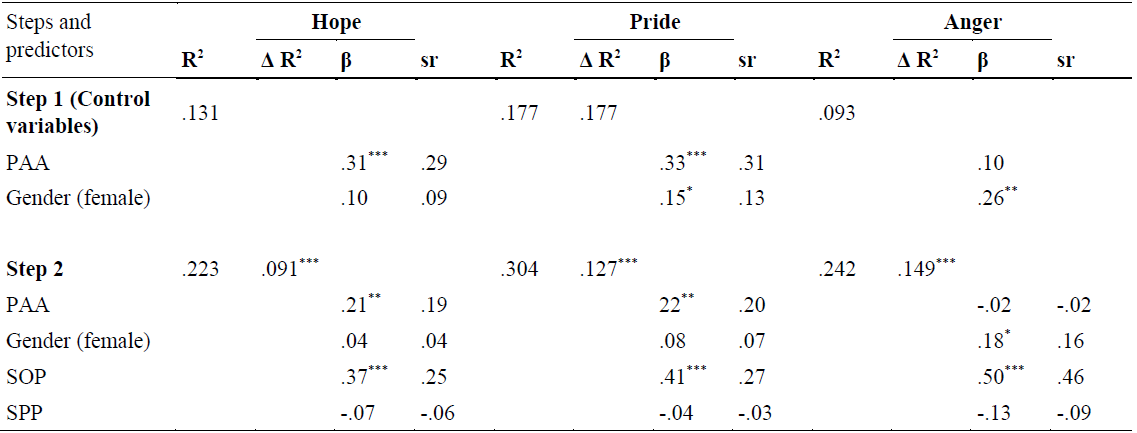

To investigate the unique relationships that perfectionism has with each test-related emotion, six

hierarchical regression analyses were conducted. We intended to explain the variation of the test-related

emotions, depending on the level of perfectionism, while controlling for academic achievement and

gender. We removed

correlations. The most research proved that real and perceived academic achievement is a good predictor

of students’ emotions. Therefore, we introduced perceived academic achievement (PAA) as control

variable in our hierarchical regression models. We also entered gender as control variable since other

papers presented gender differences in anger, anxiety and hopelessness (e.g. Pekrun et al., 2011). Thus,

for each of the six regression analyses, two hierarchical stages were conducted, with each emotion as

dependent variable. PAA and gender was entered at step 1, to control these variables. The two forms of

perfectionism were added at step 2. In Table 2 and Table 3 are presented the result of the hierarchical

regression analyses.

Regression analysis for variables predicting

significantly predicted by SOP and by PAA, while test-related anger and anxiety were significantly

predicted by SOP and gender. Guilt was significantly associated only with self-oriented perfectionism,

when the influence of other variables has been controlled. Unexpectedly, the socially prescribed

perfectionism was positively associated only with hopelessness and was not related to anxiety and anger.

7.Discussions and Conclusions

In this paper we examined a sample of high school students in a correlational design, in order to

find out the individual contribution that the self-oriented and socially prescribed perfectionism has in

explaining variation of some academic emotions. Compared to other researches that have investigated the

relationship between perfectionism and emotions, this study was focused on a specific category of

emotions, namely those associated with school evaluative contexts. The results of the present research

support our hypotheses only partially. Thus, it was found indeed that self-oriented perfectionism is

significantly associated with both positive and negative test-related emotions, if the

self-oriented perfectionism reported more test-related hope and pride, regardless of gender. As expected, the perfectionist’s high standards were associated with hope of success. Moreover, high standards

associated with perceived academic achievement and with anticipated success predicted pride as feeling

of accomplishment and satisfaction. Concerning test-associated anger, anxiety, and guilt, results of our

research denoted a strong positive relationship between these academic emotions and the self-oriented

perfectionism, regardless academic achievement. Setting high standards and striving for performance can

be beneficial for motivation, hope and pride, but at the same time it puts pressure on the student,

generating anger, anxiety or guilt. The data of regression analysis indicated also a significant association

of anger and anxiety with female students: higher perfectionist female reported higher level of anger and

anxiety, regardless of academic achievement. These findings are consistent with those reported by Hewitt

& Flett (1991) on the association between perfectionism, trait-anxiety and anger, but also with those

reported by Pekrun

The supposed relationship between socially prescribed perfectionism and negative emotions, when

overlap of the variables was controlled, was not supported by our results. Socially prescribed

perfectionism is not correlated with anger, anxiety, shame and guilt, but only with hopelessness.

Although researchers have associated socially prescribed perfectionism with poor adjustment, it does not

means that the socially perfectionists are experiencing all the negative emotions. It is possible that the

socially perfectionist students do not reported anxiety, or anger, or guilt, because they have an external

locus of control, which does not put directly pressure on them and therefore do not produce activating

emotions, but rather deactivating emotion, such as hopelessness (see Hewitt & Flett, 1991).

Finally, this paper proved some empirical data concerning the individual differences in

perfectionism in high school students and the relationship of this psychological variable with self-

reported academic emotion related to school tests or examinations. Distinguish between adaptive and

maladaptive forms of students’ perfectionism and knowledge of their effects on emotions, motivation,

and performance is a major issue in education.

References

- Accordino, D. B., Accordino, M. P., & Slaney, R. B. (2000). An investigation of perfectionism, mental health, achievement, and achievement motivation in adolescents. Psychology in the Schools, 37, 535-545.

- Ashby, J. S., & Rice, K. G. (2002). Perfectionism, dysfunctional attitudes, and self-esteem: A structural equations analysis. Journal of Counseling and Development, 80, 197-203.

- Ashby, J. S., Rice, K. G., & Martin, J. (2006). Perfectionism, shame, and depression. Journal of Counseling and Development, 84, 148-156.

- Ashby, J. S., Dickinson, W. L., Gnilka, P. B., & Noble, C. L. (2011). Hope as a mediator and moderator of multidimensional perfectionism and depression in middle school students. Journal of Counseling and Development, 89, 131-139.

- Bento, C. Pereira, A. T., Saraiva, J. M., & Macedo, A. (2014). Children and Adolescent Perfectionism Scale: Validation in a Portuguese Adolescent Sample. Psicologia: Reflexão e Critica, 27(2), 228-232. DOI: 10.1590/1678-7153.201427203 Cox, S. L., & Chen, J. (2015). Perfectionism: A contributor to social anxiety and its cognitive processes.

- Australian Journal of Psychology, 67, 231-240. DOI: 10.1111/ajpy.12079 Damian, L. E., Stoeber, J., Negru, O., & Băban, A. (2014). Perfectionism and achievement goal orientations in adolescent school students. Psychology in the Schools, 51, 960-971. DOI: 10.1002/pits.21794 Einstein, D. A., Lovibond, P. F., & Gaston, J. E. (2000). Relationship between perfectionism and emotional symptoms in an adolescent sample. Australian Journal of Psychology, 52, 89-93. DOI: 10.1080/00049530008255373

- Fedewa, B. A., Burns, L. R., & Gomez, A. A. (2005). Positive and negative perfectionism and the shame/guilt distinction: Adaptive and maladaptive characteristics. Personality and Individual Differences, 38, 1609-1619. DOI:10.1016/j.paid.2004.09.026 Flett, G. L., Blankstein, K. R., Hewitt, P. L., & Spomenka, K. (1992). Components of perfectionism and procrastination in college students. Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal, 20(2), 85-94. DOI: 10.2444/sbp.1992.20.2.85 Flett, G. L., Hewitt, P. L., Boucher, D. J., Davidson, L. A., & Munro, Y. (1997). The Child-Adolescent Perfectionism Scale. Development, validation, and association with adjustment. Unpublished Manuscript, York University, Toronto. Retrieved from http://hewittlab.psych.ubc.

- ca/files/2014/11/CAPS.pdf Frost, R. O., Marten, P., Lahart, C., & Rosenblate, R. (1990). The dimensions of perfectionism. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 14(5), 449-468. DOI: 10.1007/BF01172967 Hewitt, P. L., & Flett, G. L. (1991). Perfectionism in the self and social contexts: Conceptualization, assessment, and association with psychopathology. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 60, 456-470.

- Hewitt, P. L., Caelian, C. F., Flett, G. L., Sherry, S. B., Collins, L., & Flynn, C. A. (2002). Perfectionism in children: Associations with depression, anxiety, and anger. Personality and Individual Differences, 32, 1049-1061.

- Pekrun, R., Elliot, A. J., & Maier, M. A. (2006). Achievement goals and discrete achievement emotions: A theoretical model and prospective test. Journal of Educational Psychology, 98, 583-597. DOI: 10.1037/a0013383 Pekrun, R., Elliot, A. J., & Maier, M. A. (2009). Achievement goals and achievement emotions: Testing a model of their joint relations with academic performance. Journal of Educational Psychology, 101, 115-135. DOI: 10.1037/0022-0663.98.3.583 Pekrun, R., Goetz, T., & Perry, R. P. (2005). Academic Emotions Questionnaire (AEQ) User’s manual, of Psychology, University of Munich. Retrieved from Department https://www.scribd.com/doc/217451779/2005-AEQ-Manual Pekrun, R., Frenzel, A. C., Goetz, T., & Perry, R. P. (2007). The control-value theoryof achievement emotions:An integrative approach toemotions in education. In P. A. Schutz & R. Pekrun (Eds.), Emotion in education (pp. 13-36). San Diego: Academic Press.

- Pekrun, R., Goetz, T., Titz, W., & Perry, R. P.(2002).Academic emotions in students’ self regulated learning andachievement: A program of qualitative andquantitative research. Educational Psychologist, 37, 91-105. Retrieved from http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:bsz:352-138856 Pekrun, R., Goetz, T., Frenzel, A. C., Barchfeld, P., & Perry, R. P. (2011). Measuring emotions in students’ learning and performance: The Achievement Emotions Questionnaire (AEQ).

- Contemporary Educational Psychology 36, 36-48. DOI: 10.1016/j.cedpsych.2010.10.002 Rhéaume, J., Freeston, M. H., Dugas, M. J., Letarte, H., & Ladouceur, R. (1995). Perfectionism, responsibility and obsessive-compulsive symptoms. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 33, 785-794. DOI: 10.1016/0005-7967(95)00017-R Rice, K. G., Richardson, C. M. E., & Ray, M. E. (2016). Perfectionism in academic settings. In F. M.

- Sirois & D. S. Molnar (Eds.). Perfectionism, Health, and Well-being (pp. 245-264),New York, NY: Springer. Retrieved from http://booksc.org/s/?q=Perfectionism%2C+Health%2C+and+Wellbeing+&t=0 Schutz, P. A., & Pekrun, R. (2007). Introduction to emotion in education. In P. A. Schutz & R. Pekrun (Eds.), Emotion in Education (pp. 3-10). San Diego: Academic Press.

- Slaney, R. B., Rice, K. G., Mobley, M., Trippi, J., & Ashby, J. S. (2001). The Revised Almost Perfect Scale. Measurement and Evaluation in Counseling and Development, 34, 130-145.

- Stoeber, J., & Rambow, A. (2007). Perfectionism in adolescent school students: Relations with motivation, achievement, and well-being. Personality and Individual Differences, 42, 1379-1389.

- DOI: 10.1016/j.paid.2006.10.015 Stoeber, J., Kobori, O., & Tanno, Y. (2013). Perfectionism and self-conscious emotions in British and Japanese students: Predicting pride and embarrassment after success and failure. European Journal of Personality, 27, 59-70. DOI: 10.1002/per.1858

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

25 May 2017

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-022-8

Publisher

Future Academy

Volume

23

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-2032

Subjects

Educational strategies, educational policy, organization of education, management of education, teacher, teacher training

Cite this article as:

Curelaru, V., Diac, G., & Hendreș, D. M. (2017). Perfectionism in High School Students, Academic Emotions, Real and Perceived Academic Achievement. In E. Soare, & C. Langa (Eds.), Education Facing Contemporary World Issues, vol 23. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 1170-1178). Future Academy. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2017.05.02.144