Abstract

Lately, evaluation gets an increasingly important place in teaching. In such a context, it becomes ever more necessary to deal as carefully as possible with this field of education sciences. In this study we considered evaluation as an intrinsic component of the teacher-student relationship. The quality of evaluation influences to a great extent the very performance of the student and the confidence one’s own skills. In this research we sought to reveal some aspects regarding the approach of evaluated students by a group of high school teachers (Prahova County, Romania), revealing the attitude of those who, for some time, were in the evaluator’s position. This approach of evaluation is the more relevant since we are dealing with teenage students, who are in a sensitive period of their lives, have yet unclarified and unconsolidated values, with explorations of character, with moments of confusion, self doubt, risky eccentricities, with a strong desire to clarify one’s own potential and to be reassured that he/she is not alone.

Keywords: Evaluationteacherstudentteacher-student relationship

Introduction

Lately, evaluation gets an increasingly important place in teaching. As its share rises in the

orientation and regulation of education, it becomes increasingly necessary to deal (as closely as possible)

with the conditions in which it takes place and the effect it has on the specificity and dynamics of the

relationship between evaluated and evaluator.

In this field of education sciences, some experts focus on the tools and mechanisms of evaluation,

on its functions and forms but also on the criteria and standards involved (Manolescu, 2015, 2010; Cucoş,

2008). Others also invoke - in addition - the psychological effects evaluation has on students (Bocoş,

Jucan, 2008; Robinson, 2015; Thompson, 2015).

Of course, all these aspects, structures, phases and processes are very important. They ensure the

evaluative act is accomplished under the best possible conditions. Evaluation, however, can also be

regarded relationally. In fact, it occurs within the teacher - student relationship and affects the course of its

evolution.

Therefore, it becomes relevant the way (high school) teachers devise, understand and carry out

student evaluation, considering students are adolescents (with all the age specific explorations, tensions,

rebelliousness, misunderstandings, exaggerations and uncertainties).

The study looked at how teachers should approach the evaluated students and at the teachers'

attitude in their dealings with students in general and as part of the evaluation relationship in particular.

Research Methodology

For this purpose, we used the questionnaire based survey method; we applied it during March-May

2016, to a research sample consisting of 56 subjects, teachers in high schools (urban and rural) in Prahova

County. Its structure was as follows:

Data and Results

From the application of the questionnaire and collecting the data, we obtained the following situation:

Findings, Comments and Interpretations

Based on the data we obtained, we can make the following (possible) comments and

interpretations:

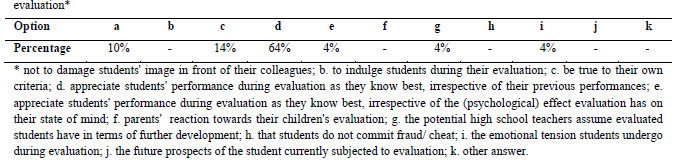

1. When asked to opt for

respondents (46%) considered it to be

most significant characteristic of their relation with their students. The next group is the one who

considered

(30%). Small percentages (8% each) went to teachers who considered

the most important features of the didactic relationship. There were also

(explicitly) invoked and suggested

options such as

not meet any percentage points. Perhaps empathy, cooperation and communication meant - to the

investigated subjects - more than indifference/ detachment, but less than compassion and attachment (if,

indeed, they really took into consideration their spiritual load, in general, and the school context, in

particular). Also very close were those who chose the option

interact with students.

Consequently, in the perception of respondents (and perhaps in their professional conscience as

well), the most suitable attitudes towards (high school) students are

complex the ratio between them might seem!)

2. Regarding

school teacher-subjects take into consideration, during evaluation, only what students know and/or solve.

They seek not to be influenced by what (or how much) students have learned until then, by the extent to

which they assimilated the (cognitive or practical) abilities required prior to the moment of the evaluation,

by the (more or less) effort students made. Also, it emerges that this segment of the respondent sample

separates

evaluated student. To them, the previous (educational) course of a student is not important (at least for

the time they worked together and the teacher could distinguish student's approach to study/ the profile of

their personality under construction). Their past may constitute, in the teacher's mind, a disturbing factor

in achieving fairness in evaluation. What matters is the

beyond those limits can only alter the evaluative act and decision.

The 64% of respondents exclude the cognitive ups and downs, previous aptitudinal performances

or the difficulties encountered by students until the moment of evaluation, the obstacles they surpassed

until then; they do not (and should not, they believe) take into account the progresses and efforts

(whenever and wherever they may be), of their motivational state (so that, if they are demotivated, they

should help them that, through evaluation, to overcome this state; or, if they are motivated, to keep it up).

In short, this category of high school teachers do not regard as opportune, during evaluation, the

connection between the present and the past of the student who is currently under evaluation.

At a distance, with 14%, there are subjects that claim their first thought is to

solved and done. It seems that, to them, what's important are the criteria and the consistency with which

they apply them/ observe them as evaluators. There is no preoccupation for the emotional state of

students, for their personal history, their efforts, hesitations and assumptions during classroom

interaction, for the motivation they manifested in the subject taught by the teacher.

We find it interesting that there is a small category of high school teachers - 10% - who declare

that, during evaluation, they (almost instantaneously) think of the image of the person in front of them.

They specify the fact that they have in mind

This category of respondents also take account of the fact that teenage (high school) students are very

sensitive to their social image: they do not want to be put to shame, be ridiculed, they want to stand out

and get attention by their 'originality' or - even - originality, and they want their value recognized. The

10% of subjects know and understand that their students go through an identity crisis and - as a

consequence - they do not want to lay stress on it (worsen it). These teachers-evaluators believe that to

their students a positive image (in the eyes of others) or one that matches their own expectations is (more)

important to the formation and evolution of personality than an extremely rigorous evaluation, that follows the requirements and standards of the curriculum too closely, more important than the way they

performed at the given time (more or less arbitrary) of the assessment of their knowledge and

competences.

It is also worthy of mentioning that such vision about evaluation and its materialization has its

shortcomings/ disadvantages: even if we are preoccupied by the prestige of the students under evaluation

in front of their colleagues we cannot stray too far from the criteria for passing the exams, for establishing

the extent to which they have or operate acquired knowledge (as many as they might have) as per the

requirements of official school documents. We understand, thus, that in evaluation we have to take into

account several benchmarks: curriculum, criteria, correctness-equidistance, system's policies, the

aspirations of the given school administration, the social image of the evaluated student, currently in a

delicate position, rather troubled from the point of view of their self-identity, etc.

There were other options as well, each listed with a 4%: some have claimed their first thought

when evaluating is

means this minor category links the present of the student's evaluation to the potential they foresee in

him/her, manifested into a more or less near/ distant future); another 4% revealed the first thought that

comes to mind almost as if by reflex when evaluating students is

not go indifferent to the emotional charge involved by any act of human evaluation. There are also

teachers (as many or few as they may be!) who think at the emotions (caused by the uncertainties, gaps,

confusions and impediments of students) of those who are forced to face the complexity, hazard and

constraints of evaluation.

Looking further carefully, we notice that no subject has chosen the options referring to:

or to evaluate

mature, apt to take on responsibility for what they do, without considering that current evaluations make

up - one way or another, from a certain existential perspective - the experiences that support disciples in

the future.

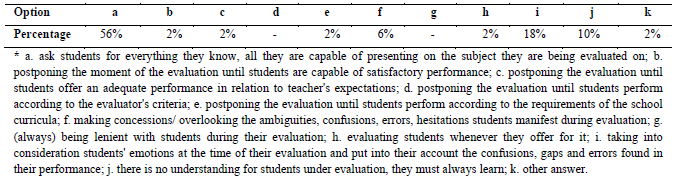

3. Regarding

investigated teachers (56%) perceive understanding towards students as the

not narrow it down to the requirements, expectations, standards and strict content of the topic under

evaluation, but are interested about all the evaluated students have to offer on the

understanding is when the evaluator adopts a broader vision about students' performance seeking to find

whether they are indeed worthy to pass the exam or not.

Understanding in what concerns students under evaluation does not require mechanical, dry and

highly exact reproduction of the contents of a test-subject, in which the student does not feel involved and to which they do not bring any personal note or contribution. It is important to see how they approach the

subject, how they lead their presentations, what the students' searches in relation to the topic are, what

language they use and what solutions think to be most viable. In short, being understanding in an

evaluative context represents, for most high school teachers,

There are, however, at a distance (leading with 18%), teachers for whom student understanding

means

student understanding - put stress on the emotional state of mind of the evaluated student, which in many

situations plays an important role in their ability to gather and organize their thoughts/ ideas, be clear and

concise in expression (be it oral or written), in offering an original take on the test-subject.

The following category (10%) comprises (high school) teachers who believe that

believe - of scientific and professional interest to see how this category of respondents works with their

students, what is the atmosphere in their classrooms, what motivates their students and what level they -

constantly - reach in their results, that is to say what sort of people enter society after graduation.

Unlike this way of treating understanding in an evaluative context, 6% of subjects considered that

understanding the students under evaluation means

understand understanding in an extremely broad sense, which undermines the evaluative act itself.

Perhaps for teachers who are sure of their students and are skilled in the theory and practice of evaluation,

a certain option appears unacceptable, even fanciful.

From the collected data, it emerged that respondents do not assimilate understanding in evaluation

with

under-prepared, but neither with

Conclusions

In the functioning of a school system and of school in general, evaluation became a key point and

a capital concern. Apparently it went to the fore. It is not a cut and dry operation. It represents (and it

always will) a field to be explored, researched. It is an unknown variable worthy of being solved, as with

any other unknown variable which elicits temptation of the investigation and courage alike (when facing

the expected, and especially the unexpected risks).

In our research we have departed from the (assumed) premise that any evaluation takes place

within the teacher-student relationship. Apart from the inherent emotional charge, it implies a certain

attitude of the evaluator during its process. The teacher may opt for maintaining the behavior they

adopted in the period prior to the evaluative act or they may change it; as a consequence, they may have a

consistent attitude in their relationship with students, or one adapted to the various stages of the didactic

process.

We considered that, in evaluation, at least two aspects are worthy of being studied: one, that

referring to the first thought that comes to mind almost instantly to teachers when they enter the role of evaluators; the other, referring to the way they relate to the special situation their students find themselves

in for a certain amount of time.

Based on the accuracy with which they know their students, on their interest for their healthy

development, based on their psycho-pedagogical culture, the peculiarities of their relationship with

students (throughout their entire professional career, in general, and with those currently under

evaluation, in particular), on their human and teaching experience, on the depth of its understanding, the

teachers-evaluators may manifest a certain understanding towards the students under evaluation or they

may be indifferent and distant considering any form of understanding alters and distorts the results of

their evaluation.

Our modest study (which may be continued, deepened, extended) it emerges that it is important to

include the teacher student relationship into the concept and practice of evaluation. It is a significant

element, the more so since we are dealing with teenage students, who are in a sensitive period of their

lives, have yet unclarified and unconsolidated values, with explorations of character, with moments of

confusion (sometimes even potentially compromising), with strong mimetic tendencies (usually frivolous

behaviors), self doubt, risky eccentricities or prolonged loneliness.

High school students need as clear and honest as possible an attitude from the teacher - including

during evaluation - to better know themselves, to clarify of their own potential, to know that they are not

deserted or considered incapable and it is very important in life to offer the world what we are capable of,

as far as our talent and good faith allow it.

References

- Bocoş, M., Jucan, D. (2008). Teoria şi metodologia instruirii. Teoria şi metodologie evaluării.

- Repere şi instrumente didactice pentru formarea profesorilor. Ediţia a III-a. Piteşti: Editura

- Paralela 45

- Cucoş, C. (2008). Teoria şi metodologia evaluării. Iaşi: Editura Polirom

- Manolescu, M. (2015). Referenţialul în evaluarea şcolară. Bucureşti: Editura Universitară

- Manolescu, M. (2010). Teoria şi metodologia evaluării. Bucureşti: Editura Universitară

- Robinson, K., Aronica, L. (2015). Şcoli creative. Revoluţia de la bază a învăţământului. Bucureşti:

- Editura Publica

- Thompson, M. (2015). Educaţia fără constrângere. Bucureşti: Editura Herald

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

25 May 2017

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-022-8

Publisher

Future Academy

Volume

23

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-2032

Subjects

Educational strategies, educational policy, organization of education, management of education, teacher, teacher training

Cite this article as:

Albu, G. (2017). Secondary Education Teachers’ Approach to Evaluation. Case Study. In E. Soare, & C. Langa (Eds.), Education Facing Contemporary World Issues, vol 23. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 1083-1089). Future Academy. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2017.05.02.133