Abstract

This research analyses the relationship between fundamental emotions and occupational stress in educational settings, the nature and dynamic of this relation, as well as individual (physical health and psychological wellbeing) and organizational (efficiency and effectiveness) consequences in educational settings. From a Narrative Interpretive Perspective (

Keywords: Fundamental emotionsoccupational stress in school environmentphysical healthpsychological wellbeing

Introduction

Emotions play an important role in daily life, in interpersonal relationships and in our connection

to the environment around.

They have various causes and determine a variety of response reactions, at physiological,

psychological and behavioural levels. The intensity of subjective experiences and personal coping styles can generate stress. Stress is an

intrinsic dimension of everyday life, with interpersonal, organizational and social meanings.

The research literature has approached stress from a variety of perspectives:

a. as an adaptive physical and/or psychological response of the person to the action of many

aspects of disruptive events (H. Selye);

b. as a stimulus generating a physical reaction;

c. the transactional/interactional approach in which the focus is on the relationship between the

environment and the person, and stress is a moderating variable

The main representative of the latter approach is Lazarus, who studied stress for over 30 years. He

defined the concepts of cognitive evaluation (primary and secondary), coping mechanisms, and the role of

emotions in such coping strategies. In his framework, attention is given to occupational stress, also called

„organizational” or „professional” stress.

The present research focuses on the relationship between emotion and occupational stress in

teachers, the nature and dynamics of this relationship in educational settings and its consequences on

individual wellbeing (physical health and psychological wellbeing) and organizational productivity

(efficiently and increase the effectiveness of educational activity).

This study departed from the following objectives:

1. to identify and measure fundamental emotions in an educational setting

2. to identify and measure two dimensions of affectivity: Positive affectivity (AP) and negative

affectivity ( AN), and to determine the inter-individual differences for each, considering gender

3. to determine the inter-individual differences for each fundamental emotions, considering gender

and age .

4. to determine the emotional profile of teachers based on inter-individual differences between

positive affectivity and negative affectivity and for each fundamental emotions, from gender and age.

A number of 270 professionals from pre-school institutions in Timis, Hunedoara and Caras-

Severin counties participated in this study. Of these, 175 were women (64, 81 %) and and 95 were men

(35 , 18% ); the age mean is 44,6 years (SD=7,76). We grouped the respondents in two age groups: 148

aged 25 to 40 (95 women and 43 men) and 122 aged 41 to 62 (80 women and 42 men).

Research Instruments

2.1. To determine the positive and negative affectivity and to identify the fundamental emotions

we used the extended version of the PANAS QUESTIONNAIRE (Positive and Negative Affect Schedule

– Expanded Version) by David Watson and Lee Anna Clark (1994), which measures positive affectivity

(AP) negative affectivity (AN) and 11 fundamental emotions: fear, sadness, guilt, anger, shyness, fatigue,

surprise, joy, pride, conscientiousness and serenity.

2.2. Depression – Anxiety – Stress Scale (The Depression Anxiety Stress Scales - DASS) by

Lovibond and Lovibond (1995) which measures depression, anxiety and stress. We used the short version

of DASS 21, consisting of 21 questions.

2.3. ASSET (A Shotrend Stress Evaluation Tool) a short evaluation inventory of stress by

Carwright and Cooper , translated and elaborated for Romanian population by Pitaru, Tureanu and

Peleasa in 2008, was used for the measurement of stress levels in organizations, the stress intensity felt by

the employees and to identify the source of stress for different organizational groups.

ASSET identifies and measures 8 categories of stress sources: professional relationships, work-life

balance, work overload, job security, control, communication, particular aspects of workplace but also the

consequences of stress in terms of physical health and psychological wellbeing.

The research hypotheses:

1. The negative fundamental emotions manifest more frequently then positive fundamental

emotions in educational settings

2. There are differences between male and female teachers in the manifestation of fundamental

positive and negative emotions

3. There are differences between teachers aged 25-40 years old and those aged 41-62 in the

manifestation of positive fundamental emotions and that of negative fundamental emotions.

To identify and measure fundamental emotions in school organizations, the Inventory Panas-X for

positive and negative emotions was used.

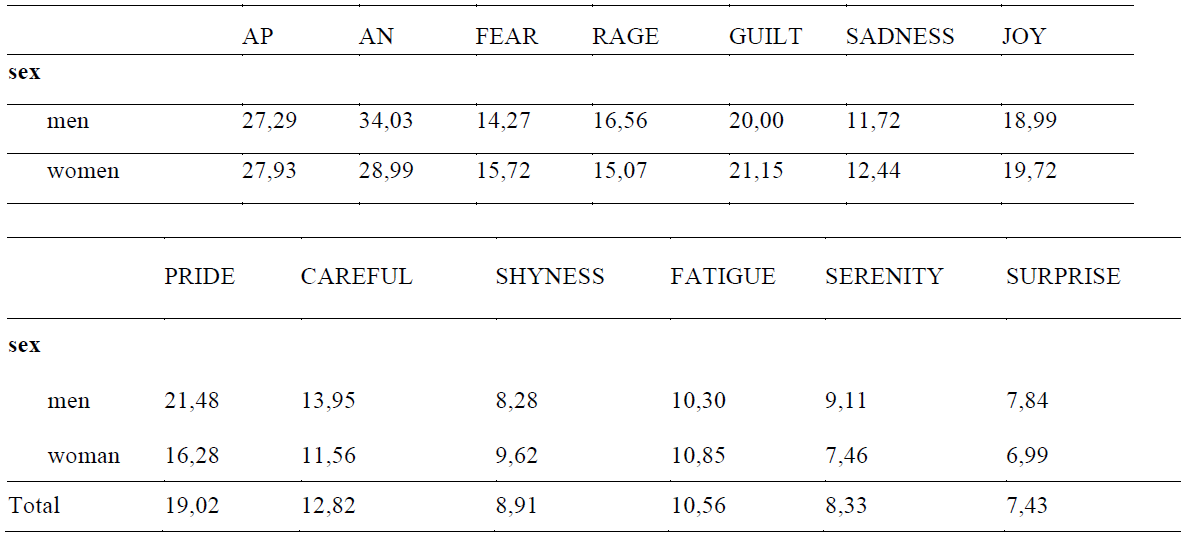

Analyses of the results highlight the fact that obtained the heights score to negative affectivity

AN, (m = 31,64, sd = 7,15), followed by positive affectivity AP (m = 27,59, sd = 4,917), guilt (m = 20,54

sd = 5,36), pride (m = 19,02, sd = 5,14), joy (m = 18,90, sd = 5,36), rage (m = 15, 85, sd = 3,39), fear (m

= 14,95, sd = 2,79), sadness (m = 12,82, sd = 3,23 ), careful (m = 12,06, sd = 3,92 ),fatigue (m = 10,56, sd

= 2,80), shyness (m = 8,91, sd = 2,74), serenity (m = 8,33, sd = 2,48) and surprise (m = 7,43, sd = 1,68).

In order to test the hypothesis of the existence of statistical differences in the manifestation of

positive affectivity and the negative affectivity, we applied the t test for independent samples.

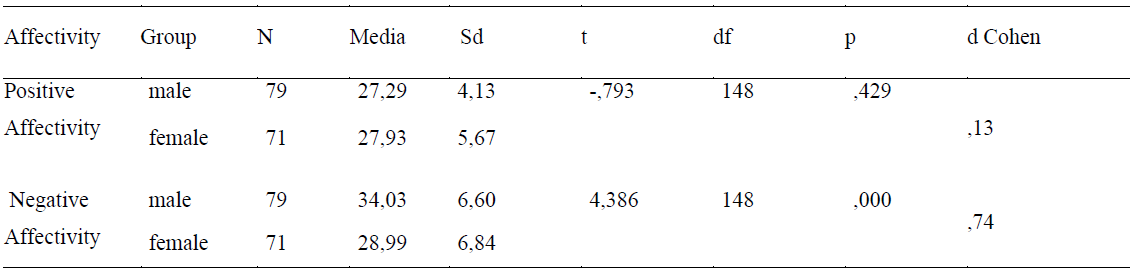

Our results presented in table

(m=27,59, sd=4,91) and negative affectivity (m=31,64,sd=7,15), as the T-test analyses show.

For pair samples the t test showed statistical differences to be significant between manifestation of

positive affectivity and the negative affectivity (149) = -4,95, p>.001, to the effect size was medium a

(d=,66).

From these results the hypotheses confirm that negative fundamental emotions (AN) are more

frequently manifested than positive fundamental emotions (AP) in educational settings.

Our research results are within the line of previous empirical studies which show that negative

emotions are frequently experienced in an organizational environment, especially in the competitive

power environment (Lazarus, 2006; Spector, fox & Van Katwyk, 1996; Payne & Cooper, 2001).The

negative affectivity entails living unpleasant emotions like: fear, rage sadness, guild, envy, shame, etc.,

and it is associated with low levels of group cohesion. Guilt is frequently experienced at work, and

together with fear, anger rage and sadness, form the category of negative emotions considered to have

negative effects in an organizational environment and also called ,,stressful emotions’’(Lazarus, 2006).

The second fundamental emotion identified here is „pride” a positive emotion that boosts self

esteem at a personal and group level, but at the organizational level it has a negative impact by prompting

competition among person/group /group cohesion. The third identified fundamental emotion ,,the joy’’ is

related to the experience of wellbeing and together with pride and conscientiousness represent the

positive fundamental emotions defined hereby as positive affectivity that is associated with job

satisfaction ,increased productivity (Lyubomirsky, King & Diener, 2005), decreased levels of

absenteeism (Thoresen, Klan & Barsky, 2003), a positive influence on conflict mediation in negotiation

(Barsade, 2002), creativity growth (James, Broderse & Jacob, 2004 cit. in Bersade & Gipson, 2007), an

improvement of physical health and wellbeing at work, etc.

Our results revelled lower scores of other fundamental emotions like fatigue shyness, serenity and

surprise.

To verify the second research hypotheses we applied the t test for the independent samples. Our

data indicate differences between men (m=27,29, sd=4,13) and women (m=27,93, sd=5,60) as regards

positive affectivity, yet the difference was not statistically significant (d=0,13).

For the independent samples the t test shows the significant differences between men and women

for negative affectivity AN: t(148)=4,38, p<.001, the effect size being highest (d=0,74). Men exhibit to a

greater extent negative emotions (m=34,0,3,sd=6,60) than women (m=28,99,sd=6,84) at work and the

difference is statistical significant .

Based on these results we concluded that there are no statistically significant differences between

the manifestation of positive fundamental emotions in female and male employees at work.

Men recorded higher scores for rage, joy, pride, serenity and surprise, and women scored higher

on guilt, sadness, shyness and fatigue. Results are presented in Table 4.

Our results are, to a certain degree, different than others in this field of study. Watson and Clark

(1994) mention that general dimensions, like positive and negative affectivity, surprise and sadness are

not sensible to gender, whereas in our study only negative affectivity shows no connection to

respondents’ gender.

The results we obtained confirm results reported by other studies, where women registered higher

scores for

In order to test our hypotheses, concerning the manifestation of the fundamental positive and

negative emotions in relation to age, we proceed to applying the

whether there is or there is not any difference between scores obtained by participants aged 25 to 40, and

participants aged 41 to 62, and, moreover, if this difference is statistically significant.

The empirical data we obtained shows that for the age group 25 to 40, positive affectivity (PA) is

manifested to a smaller degree (m = 25.04, sd = 4.04) as compared to age group 41 to 62 (m = 29, 71, sd

= 4,57), but considering

the difference is not statistically significant.

The

participants younger than 40 manifest negative emotions to a higher degree (m = 33,19, sd = 6,60) than

participants aged 41 to 62 (m = 30,35, sd = 7,79), in an educational environment, the difference being

statistically significant.

Subsequent to applying variance analysis, we can consider that

The younger participants aged 25 to 40, manifest positive emotions to a smaller degree than

participants aged 41 to 62, but the difference is not statistically significant.

In the same way, the data we obtained permits us to specify that

negative affectivity (NA), but the ones aged 25 to 40 do it to a greater degree, than those aged 41 to 62.

The younger manifest negative affectivity to a greater degree than positive affectivity, as showed

in Lazarus, Pimley şi Novacek (1987, apud. Lazarus, 2006), Cartensen, Graff, Levenson and Gottman

(1996, apud. Lazarus 2006). More recent studies (Pelfrene et al., 2001, Nogueras, 2006) show that with

age, people manifest more positive than negative emotions.

Considering the need for a new perspective in studying emotions, the narrative-integrative view

respectively (Lazarus, 2006), that surpasses the limits of previous theoretical views which focused on the

general dimensions of affectivity, on the axis of positive-negative, pleasant-unpleasant, activation-

inhibition, etc., or studying one of the fundamental emotions in a determined context, our process in this

study was to identify and measure both the two meta-constructs –

fundamental emotions, and the way these emotions relate to the pressure sources of the organisational

level, according to an interpretative-explicative and integrative model, that adequately meets the needs of

a study concerning organisational stress (Cartwright & Cooper, 2002).

The results of our study determine the existence of a relationship between the manifestation of

fundamental emotions, especially that of negative emotions, and a higher level of work stress in

educational settings. At this level we find manifest the negative affectivity, as a general dimension, and

negative emotions, like

Our results are supported by a large series of empirical studies, showing that negative emotions

manifest in strongly competitive environments (Lazarus, 2006; Spector, Fox &Van Katwyk, 1996; Payne

& Cooper, 2001).

The manifestation of negative emotions is associated with perception of the stress source (control,

professional relationships, workplace certainty, work-personal life balance, work overload, particular

aspects of working place payments and benefits) while the manifestation of the positive emotions is

associated with a higher resistance to stressors (workplace certainty, professional relationships, payments

and benefits).

The fundamental emotions and the stress

The literature reports more studies proving the existence of a positive correlation between negative

affectivity and an overload in work stress.

Our research results show that the manifestation of negative fundamental emotions correlates with

lower levels of physical health and psychological wellbeing. Negative affectivity is related to

consequences on psychological wellbeing to a larger extent than to consequences on physical health. In

other words, negative affectivity has a greater impact on psychological wellbeing than on physical

wellbeing.

As far as psychological wellbeing is concerned, our results highlight that, as the employee

manifests more negative emotions (

decrease. The strongest correlation exists between

manifested the fear, the lower her psychological well-being.

psychological well-being of employees in educational work settings.

The data we obtained highlight a negative correlation between positive emotions like

the lower the signs and symptoms of impaired well - being.

Our results show that the strongest predictor of

experienced at work is accompanied by feelings of discomfort, caused by injustice, and it determines

aggressive reactions of defence (verbal, physical violence, threats) (Fitness, 2000, cit. în Kkiewitz,

2002), open conflict with others, resistance to change (Folger & Skarlicki, 1999, cit. în Kkiewitz, 2002).

Conclusions

The results of our study confirmed the existence of a relationship between the expression of

fundamental emotions, especially the negative ones, and a high level of stress in organizational settings,.

Thus, the expression of negative emotions is related to the perception of environmental stressors (control,

professional relations, job security, work-life balance, overwhelming tasks, other workplace-related

aspects such as salaries and perks), while the expression of positive emotions is associated to a higher

resistance to stressful factors (job security, work relations, salaries and perks).

Based on the results of the study we can conclude that there is a relationship between the

expressions of negative emotions especially that of negative ones, and a high level of stress in educational

work settings.

Emotions such as guilt, fear and anger might explain a negative impact on physical health, while

joy, as a positive emotion, predicts a beneficial influence on health.

Fundamental emotions such as guilt, fear, anger, joy, pride and surprise explain and predict

psychological wellbeing in the organization. It is worth noting that four of the studied emotions – guilt,

fear, anger and sadness, predict a low level of psychological wellbeing. The strongest predictor of

psychological wellbeing is anger.

References

- Barsade, S.G. (2002). The ripple effect: Emotional contagion and its influence on group behavior.

- Administrative Science Quarterly,47(4), 644–675.

- Barsade, S.G., & Gipson, D.E. (2007).Why does affect matter in organizations? Academy of

- Management Perspective, 5,36-59.

- Cartwright, S., & Cooper, C.L. (1997). Managing Workplace Stress, Londra: Sage.

- Cartwright, S., & Cooper, C.L. (2002). ASSET: Management guide, Manchester: Robertson Cooper Ltd. Crawford, J. R., & Henry, J. D. (2004). The Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS): Construct validity, measurement properties and normative data in a large non-clinical sample. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 43, 245-265.

- Lazarus, RS. (2006). Stress and emotion: a new synthesis, New York: Springer Publishing Company. Lovibond, S. H., & Lovibond, P. F. (1995). Manual for the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales. Sydney: Psychology Foundation.

- Lyubomirsky, S., King, L., & Diener, E. (2005). The benefits of frequent positive affect: Does happiness lead to success? Psychological Bulletin, 131, 803–855. Mistreatment. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 12, 35-50.

- of Nogueras, D. J. (2006). Occupational commitment, education, and experience as a predictor intent to leave the nursing profession. Nursing Economics, 24 (2), 86-93.

- Payne, R.L., & Cooper, C.L. (Eds.) (2001). Emotion at work: theory, research, and applications for management. West Sussex: Wiley & Sons.

- Pelfrene, E., Vlerick, P., Mak, R. P., Smet, P., Kornitzer, M., & DeBacker, G. (2001). Scale reliability and validity of the Karasek „Job demand – control - support‟ model in the Belstress study. Work and Stress, 15 (4), 297 – 313.

- Selye (1980). Guide to stress research, vol1. New York: Van Nostrand, 1980.

- Selye, H. (1956). The stress of life. New York: McGraw-Hill Book Co.

- Spector, P.E., Fox, S., & Van Katwyk, P.T. (1999). The role of negative affectivity in employee reactions to job characteristics: Bias effect or substantive effect?, Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 72, p. 205-218 Thoresen, C.J., Kaplan, S.A., Barsky, A.P., Warren, C.R., & Chermont, K. (2003). The affective underpinnings of job perceptions ans attitudes: A meta-analytic review and integration. Psychological Bulletin, 129, 914-945.

- Watson, D., & Clark, L. A. (1994). Emotions, moods, traits, and temperament: Conceptual distinctions and empirical findings. În P. Ekman şi R.J. Davidson (Eds.) The nature of emotion: Fundamental questions, 89 - 93, New York: Oxford University Press.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

25 May 2017

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-022-8

Publisher

Future Academy

Volume

23

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-2032

Subjects

Educational strategies, educational policy, organization of education, management of education, teacher, teacher training

Cite this article as:

Dumitru, I., & Bersan, O. S. (2017). The Relation Between Fundamental Emotions And Occupational Stress In Educational Settings. In E. Soare, & C. Langa (Eds.), Education Facing Contemporary World Issues, vol 23. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 924-931). Future Academy. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2017.05.02.113