Abstract

In a major book in cognitive linguistics,

Keywords: Conceptual metaphorsmetaphors for teachingteacher's roleteacher-student interactions in primary school

Introduction

According to the traditional view in linguistics and language studies, metaphors are mental

constructs used mostly in poetry and creative writing for artistic and aesthetic purposes. Probably this

perspective is still prevalent today outside the linguistic domain: most of us tend to view metaphors

primarily as figures of speech, elements of poetic imagination, contributing to the aesthetic force of the

text and discourse. The seminal work entitled

and M. Johnson, challenged this traditional view, founding the

metaphor theory.

In the main corpus of cognitive linguistics, language is viewed as a part of human cognition and as

an expression of thinking, embedded and situated in the external environment. Thus, from a cognitive

point of view, metaphors are primarily a matter of thinking and secondarily a matter of language. Lakoff

and Johnson (1980; 1980/2008) argue that metaphors are primarily units of every-day thought, not only

elements of figurative language. "Primarily on the basis of linguistic evidence we have found that most of

our conceptual system is metaphorical in nature", claim the two authors (p. 92/124). Mental concepts are

basic units of thinking, fundamental knowledge structures that shape the way we perceive the surrounding

reality, reasoning and understanding, the way we act and relate to the others. Assuming that our

conceptual system is largely metaphorical, then we must agree that metaphors are "pervasive in every-day

life" and "the way we think, what we experience, and what we do every day is very much a matter of

metaphor" (Lakoff & Johnson, 1980/2008: p. 92/124). Abstract concepts we use in everyday life - like

time, change or beliefs - are understood metaphorically (e.g. time is space or resource, change is motion,

beliefs are possessions or loved objects).

Conceptual metaphors allow us to express and understand an idea or a conceptual domain, usually

one that is more abstract and ill-structured (

familiar (

Conceptual metaphors involve a set of correspondences between features or constitutive elements of the

source to the target domain. Conceptual or metaphorical

correspondences established between constituents elements of the source and the target domain.

Metaphorical mapping preserves "the cognitive topology of the source domain [...] in a way consistent

with the inherent structure of the target domain" (Lakoff, 1993). All metaphors highlight some aspects of

the target domain and they hide or elude other aspects. A number of elements of the target concepts are

not pre-existing, they are imported from the source domain through metaphoric construction (Deignan,

2005). For example, if we metaphorically conceptualise the learning

(source domain) we will tend to focus primarily on the results and secondarily on the process itself

(including here methods, obstacles, social interaction, etc.). If we conceptualise the learning

final

to the target domain the idea that academic success is mostly a matter of abilities (as when we try to reach

a real target) and, in the second case, we tend to import the idea that academic success is mostly a matter

of determination, perseverance and personal implication.

The analogical mapping between domains involved in metaphoric construction is mainly an

implicit/automatic process and metaphors are integral parts of our ordinary thought and language.

social interactions, emotions and actions, beliefs about life and death. "Metaphors are so commonplace

we often fail to notice them" said Lakoff and Turner (1989). The proponents of the conceptual metaphors

theory argue that metaphoric thought is not a peripheral form of thought since "few or even no abstract

notions can be talked about without metaphor" and the only option to understand them is "through the

filter of directly experienced, concrete notions" (Deignan, 2005).

By metaphoric construction we ground abstract concepts in meaning indirectly through more

concrete mental representations or units of knowledge, mostly derived from experience. In a frequently

cited example, the

comes from our knowledge about

Conceptual metaphors typically involve an abstract concept as target and a more concrete concept as their

source. Lakoff and Johnson (1980; 1980/2008; Johnson, 1987; Lakoff, 1987) adopt an embodied

cognition perspective in cognitive linguistics, arguing that our complex and most abstract conceptual

system comes - at an ultimate level of analysis - from

interactions with the world. For the two authors "concrete" experience in the world means sensory,

perceptual and motor experience as we interact and move through the world. Image schemata are

multimodal, dynamic, pre-linguistic and pre-conceptual structures, consisting of recurrent patterns of

experience structured in our mind, providing the basis for understanding and reasoning at more abstract

levels. Image schemata are pervasive in language and the socio-cultural context (Johnson, 1987). For

example, at the origin of the

a path and a direction (Lakoff & Johnson, 1980/2008, Lakoff, 1987; Johnson, 1987).

schema is another basic common image schema and it consists of a boundary distinguishing an interior

from an exterior. When we say "I have many ideas in mind" or "I have an empty mind", when we advise

somebody to "keep in mind" something or when we declare ''I don't know what is in her/his mind", we

conceptualise the human mind through a container schema.

Metaphoric construction means much more than transferring knowledge from one domain to

another; in fact metaphors play a central role in defining our everyday realities (Lakoff & Johnson,

1980/2008). Metaphors are a common presence at all levels of discourse - even in the educational

discourse - and people, students and teachers as well, use them almost automatically. The presence of

metaphors in the educational discourse and their influence on teaching, learning and related processes -

including here didactic communication, classroom interactions and affective climate, teacher's values,

attitude and actions, learning strategies, etc. - have been illustrated by Badley and Brummelen (2012) in a

book entitled: Metaphors We Teach By: How Metaphors Shape What We Do in Classrooms. For example,

a teacher who views the student mostly as a

primarily on the

strategies/methods. Teachers who conceptualise classroom communication according to the Shannon-

Weaver model - as a process of sending and receiving information - are prone to view the teaching

process mostly as a process of transmitting knowledge to the students. Metaphors, present at all levels of

the educational discourse (Block, 1992; Ben-Peretz, Mendelson & Kron, 2003; Chen, 2003) can help

teachers to articulate and construct their professional experiences (Kramsh, 2003; Nikitina & Furuoka,

2008) and guide their teaching practice (Cortazzi & Jin, 1999; Tăușan, 2011; Cook-Sather, 2003; Badley

& Van Brummelen, 2012).

Rationale and aims of the study

The language in the educational field is rich in metaphors (Badley & Van Bummelen, 2012).

There are metaphors

professionals

most cases automatically, without being aware of their use, and deliberately when they want to express in

a vivid and condensed form an idea which is difficult to explain in detail. Teachers use metaphors as

instructional tools, with the intent to: facilitate conceptual understanding in mathematics or science,

express complex knowledge, construct alternative interpretations of events, promote critical thinking and

inquiry in order to find personal meaning, organize and make sense of a large amount of data (Lakoff &

Nunez, 2000; Beger & Jäkel, 2015). Metaphors are sometimes used as tools for enhancing creative

expression, with the intent to facilitate social and emotional communication, to obtain dramatic effects or

to enhance the persuasive force of the message (Cortazzi & Jin, 1999; Deignan, 2005). Several popular

generative metaphors

about the "educational offer", "educational costs", learning is "acquisition" of knowledge),

metaphor (schools are "greenhouses", teachers are "gardeners", students are "fragile plants"),

metaphor (schools are "families", teachers are "parents"),

Metaphors in/of education are pervasive outside and inside the classroom: in official documents

and textbooks, in the instructional discourse, in the parents' and students' personal reflections, in students’

creative writing and drawings, in dedicated and popular media. Even if people use them mostly at the

implicit level, these metaphors exert a significant influence on the learning process, teaching practice,

classroom climate, teachers’ attitudes and students' behavior, assessment policies, curriculum

development, educational ideal, parental values and social expectations. Part of the school/classroom

culture, some of the most prevalent educational metaphors are desirable - for example "learning as a

knowledge construction" is an adequate mental representation in a constructivist classroom or "teacher as

conductor for an orchestra" is a good illustration for an efficient classroom management. Some other

metaphors are undesirable, implicit and probably difficult to overcome - the "container" metaphor for the

human mind or the "teacher as an absolute knowledge owner" - and others are simply overused - a book

as a symbol of knowledge, learning as a light bulb or the primary teacher as a mother (Duggan-

Schwartzbech, 2014).

Metaphors we teach by can serve as an important instrument of analysis (Oxford et al., 1998) for

classroom practices, teachers' beliefs and educational ideologies, classroom climate, students' experiences

and expectations, and learning strategies (Nikitina & Furuoka, 2008). If the teachers are aware of the

conceptual metaphors they use in/of education, they will be able to structure and to give signification to

their classroom experiences and to ameliorate their classroom practice (Bowman, 1996-1997; Nikitina &

Furuoka, 2008).

Using cognitive metaphor analysis, this study aims to investigate the mental representations of

teachers' role and teacher-student classroom interactions in primary school. The study focuses on the

education-related metaphors produced by a sample of primary school teachers selected from Romanian public schools. The results are discussed in relation to their potential relevance for creating more reflexive

teachers and for the optimization of the teaching practice.

Methodology

Participants

The study sample consisted of 105 primary school teachers, selected on a voluntary participation

basis from Romanian public schools (Alba and Hunedoara counties). The age of the participants was

between 25 and 59 years, all of them being females, all having a BSc degree in Preschool and Primary

School Education and the majority having, or pursuing, a MSc degree in Education. The majority of the

participants (N = 86) teach in public schools situated in urban areas.

Instruments

In order to investigate the teachers' conceptual metaphors about their roles and about classroom

interaction with the students, I used a quantitative method, a questionnaire. The questionnaire listed 32

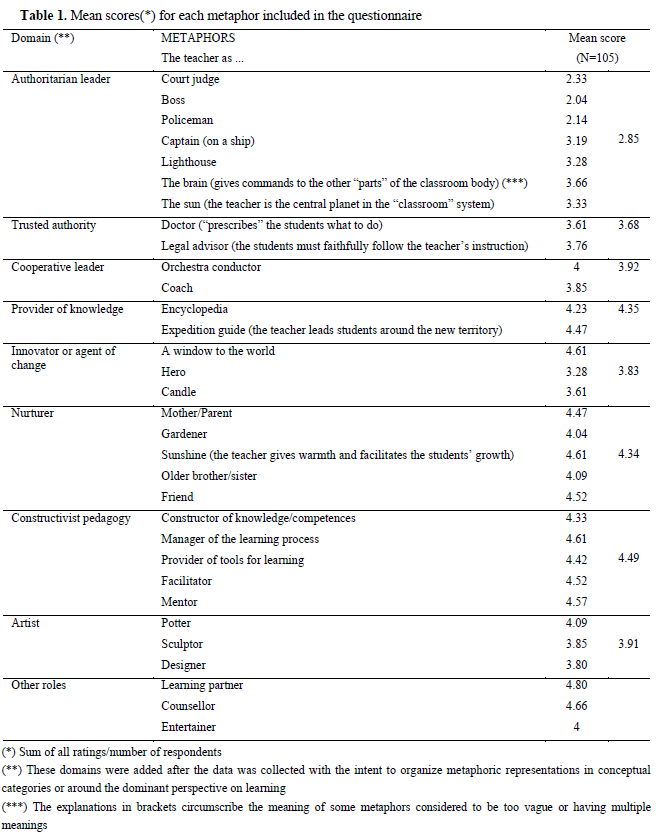

metaphors organized around several conceptual domains (Table 1). The participants were asked to

express their agreement or disagreement with each of these metaphors on a 5-point Likert-type scale

(possible ratings ranging from 1 - "strongly disagree" to "5 - strongly agree"). The participants provided

some socio-demographical data (age, years of experience in teaching, education, urban/rural location of

the school) and they completed the questionnaire anonymously.

In the first phase of the construction of the questionnaire I selected an initial list of 40 metaphors

based on a literature review (Ben-Peretz, Mendelson & Kron, 2003; Block, 1992; De Guerrero &

Villamil, 2001; Oxford et al., 1998; Nikitina & Furuoka, 2008). In a second phase, a group of 30 students

in Primary and Preschool Education were asked to finish the sentence "The teacher is like ...." with their

own metaphor and to provide a very short explanation for the given metaphor (procedure adapted after

Nikitina & Furuoka, 2008). As a result, 3 other metaphors were added to the initial list (only 3 because

most of the metaphors generated by the students were already recorded in the first list). In a third phase,

the 30 participants were asked to analyze the whole list of metaphors (43) and to rate them on a 10-point

scale (0 - irrelevant/inadequate, 10 - relevant/adequate). 32 metaphors were maintained in the final list,

after the exclusion of those with very low mean score (below 2-points).

Results

The collected data are centralized in Table 1. The mean score indicates the participants' agreement

with the metaphoric description of the teacher's role and her/his classroom status/activity (including here

teacher-student interaction). The conceptual metaphor analysis has been used as an instrument to

investigate the primary school teachers' perceptions about their role/status in the classroom context.

Discussions

The data presented in Table 1 offer a sketch of "a hidden image" of the teacher in primary school.

Cognitive metaphor analysis allows us to obtain information from the teachers about their perceived

roles, status and relations with the students involved in the learning activity. At a first glance, this

emergent "image" of the teacher appears somehow contradictory - a mixture of

4.49),

classroom, the primary school teachers view themselves mostly as

Data indicate a progressive transition from the traditional role of the teacher as "the owner" or

"depositary" of knowledge and wisdom (the mean score for the "teacher as an Encyclopaedia" metaphor

being considerably high = 4.23) to more complex roles promoted by the constructivist perspective in

education (manager of the learning process, mean score = 4.61; mentor, mean score = 4.57; facilitator,

mean score = 4.52; constructor of knowledge/competences, mean score = 4.42; provider of tools for

learning, mean score = 4.33). The view of the teacher as a

score for

Items/metaphors with the highest scores (mean scores between 4 to 5, the possible scores ranging

in the interval 1-5) are in this order: learning partner (4.80), counsellor (4.66), manager of the learning

process (4.61), window to the world (4.61), sunshine (4.61), mentor (4.57), facilitator (4.52), friend

(4.52), expedition guide (4.47), mother/parent (4.47), provider of tools for learning (4.42), constructor of

knowledge/competences (4.33), encyclopaedia (4.23), potter (4.09), old brother/sister (4.09), gardener

(4.04), orchestra conductor (4), entertainer (4). Most of these metaphors reflect the roles for teachers

prescribed by the

learning process, mentor, facilitator, provider of tools for learning, constructor of

knowledge/competences) and roles related to

gardener). The high scores assigned to metaphoric constructions like

guided, an opportunity explored out of curiosity, in the former case, and more guided in the latter one.

Authoritarian classroom roles such as court judge (2.33), policeman (2.14) or boss (2.04) had the lowest

rating scores, being avoided by the respondents.

This study offers a sketch of the primary school teachers' perceptions, beliefs and intuitions about

their roles in the classroom and about their didactic rapports and interactions with the students. Because

of the small size and demographic heterogeneity of the study sample, this investigation should be

considered rather as a preliminary pilot study, a starting point for further in-deep investigations of the

topic, but it is hoped it successfully illustrates the utility of the conceptual metaphor analysis as an

investigation tool for the teaching and learning processes.

Some of the metaphors that teachers use in describing their roles and activities in the classroom

could be considered "good" metaphors (i.e. in accordance with the dominant educational theories; for

example: facilitator, manager of the learning process or orchestra conductor). These metaphors should be

emphasized, explained in detail, bought to the teachers' attention and eventually used as didactic tools in

the teacher training programmes. Other metaphors are simply reminiscent reflections of older

perspectives on education and usually they are "imported" from the school culture (e. g. the teacher as an

encyclopaedia). They should probably be acknowledged and overcome. And others are, although

pervasive, rather overused (e. g. the teacher as a mother). For in-service teachers, metaphor analysis could

contribute to a better understanding of their beliefs and behavioral patterns in the classroom and as an

instrument of reflection and progress towards more efficient teaching practices.

Conclusions

The conceptual metaphor theory developed by Lakoff and Johnson (1980/2008) offers a valuable

frame of analysis of educational processes. Conceptual metaphors could be valuable didactic tools and

instruments of investigation in the educational field. By conceptual metaphor analysis researchers gain

access to the implicit perceptions, beliefs and cognitive representation of the teaching, learning and

classroom processes. The results and conclusions of the conceptual metaphor analysis could become

starting points for enabling teachers to become more reflexive and for optimizing the teaching practice in

primary school.

Acknowledgements

The author greatly appreciates the anonymous contribution of the primary school teachers who made this investigation possible.

References

- Badley, K. & Van Brummelen, H. (Eds.) (2012). Metaphors We Teach By: How Metaphors Shape What

- We Do in the Classroom. Eugene, Oregon: Wipf and Stock Publications.

- Ben-Peretz, M., Mendelson, N. & Kron, F. W. (2003). How teachers in different educational contexts view their roles. Teaching and Teacher Education, 19, 277–290. doi: 10.1016/S0742-051X(02)00100-2

- Beger, A. & Jäkel, O. (2015). The cognitive role of metaphor in teaching science: Examples from physics, chemistry, biology, psychology and philosophy. Philosophical Inquiries, 3(1), 89-112.

- Block, D. (1992). Metaphors we teach and live by. Prospect, 7(3), 42-55.

- Bowman, M. A. (1996-1997). Metaphors We Teach By: Understanding ourselves as Teachers and Learners. Retrieved from http://podnetwork.org/content/uploads/V8-N4-Bowman.pdf

- Chen, D. (2003). A classification system for metaphors about teaching. Journal of Physical Education, Recreation & Dance, 74(2), 24-31. doi: 10.1080/07303084.2003.10608375

- Cook-Sather, A. (2003). Movements of mind: The Matrix, metaphors, and reimagining education. Teachers College Records, 105(6), 946-977.

- Cortazzi, M. & Jin, L. (1999). Bridges to learning: Metaphors of teaching, learning and language. In L.

- Cameron & G. Low (Eds.), Researching and applying metaphor (149-176). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Deignan, A. (2005). Metaphor and Corpus Linguistics. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

- De Guerrero, M. C. & Villamil, O. S. (2001). Metaphor analysis in second/foreign language instruction: A socio-cultural perspective. Revised version of paper presented at the annual meeting of the American Association of Applied Linguistics, St. Louis, MO, February 24-27, 2001.

- Duggan-Schwartzbeck, T. (2014). 4 Bad Education Metaphors We Need to Stop Using. Retrieved from http://

- all4ed.org/bad-education-metaphors-we-need-to-stop-using

- Lukes, D. (2006). Metaphors in/of education. Presentation retrieved from

- http://www.conceptualmetaphor.net; http://www.slideshare.net/bohemicus/metaphors-in-and-of-

- education

- Johnson, M. (1987). The Body in the Mind. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Kramsch, C. (2003). Metaphor and the subjective construction of beliefs. In P. Kalaja & A.M.F. Barcelos (Eds.), Beliefs about SLA: New research approaches (109-128), Springer.

- Lakoff, G. (1987). Women, Fire and Dangerous Things. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Lakoff, G. (1993). The Contemporary Theory of Metaphor. In A. Ortony (Ed.). Metaphor and Thought(2nd ed., pp. 202-251). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Lakoff, G. & Johnson, M. (1980). The Metaphorical Structure of the Human Conceptual System.

- Cognitive Science, 4, 195-208. doi: 10.1207/s15516709cog0402_4

- Lakoff, G. & Johnson, M. (1980/2008). Metaphors We Live By. University of Chicago Press.

- Lakoff, G. & Nunez, R. (2000). Where Mathematics Comes From: How the Embodied Mind Brings Mathematics into Being. New York: Basic Books.

- Lakoff, G. & Turner, M. (1989) More than Cool Reason: A Field Guide to Poetic Metaphor. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Nikitina, L. & Furuoka, F. (2008). Measuring Metaphors: A Factor Analysis of Students’ Conceptions of Language Teachers. Metaphorik.de,15, 161-180.

- Oxford, R., Tomlinson, S., Barcelos, A., Harrington, C., Lavine, R. Z., Saleh, A. & Longhini, A. (1998).

- Clashing metaphors about classroom teachers: Toward a systematic typology for the language teaching field. System, 26(1), 3-50.

- Saban, A., Koçbeker B. N. & Saban, A. (2006). An investigation of the concept of teacher among prospective teachers through metaphor analysis. Educational Sciences: Theory & Practice 6(2), 509-522.

- Tăușan, L. (2011). Adapting school to meet the demands of students: a condition for forming an efficient learning style. Journal Plus Education, 7(1), 125-137.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

25 May 2017

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-022-8

Publisher

Future Academy

Volume

23

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-2032

Subjects

Educational strategies, educational policy, organization of education, management of education, teacher, teacher training

Cite this article as:

Todor, I. (2017). Metaphors About Teachers Role and Didactic Interactions in Primary School. In E. Soare, & C. Langa (Eds.), Education Facing Contemporary World Issues, vol 23. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 847-855). Future Academy. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2017.05.02.103