Abstract

As a malleable, potent curricular tool with numerous positive outcomes in students’ personal, academic and social lives, Service-Learning (S-L) has lately gained an increased interest from the scientific community. The most important challenge in introducing S-L instructional strategies in academic practice is designing effective, pragmatic S-L programs directed towards both reforming education by enhancing pre-service teachers’ experiences and addressing community needs. Following the systematic review algorithm, this paper focuses on summarizing novel trends and procedures in higher education S-L courses for pre-service teachers and on outlining a best practices profile. The systematic review is based on key research questions that reveal the following aspects of the S-L programs: the major scope of the programs, the most common types of programs, the hosting environment chosen by project managers, the types of activities included in such programs, the architecture of the mandatory reflection component of S-L programs, as well as the duration and evaluation techniques of the programs. The findings may serve as a reference point in designing more efficient S-L programs.

Keywords: Service-LearningPre-Service TeachersHigher Education

Introduction

In recent years, educators have made great efforts to surpass the passive, traditional methods of instruction and to actively change the pedagogical process from one of knowledge transmission to one of knowledge transformation (Carringtonm & Selva, 2010) by approaching it through Service-Learning (S-L) lenses. S-L is defined as a reflection-oriented pedagogy that combines volunteering with well-structured learning opportunities (Heffernan, 2001), facilitating pre-service teachers’ emergence from the theoretical world into professional practice, by engaging community service with academic content through well-defined operational objectives (Rusu, Copaci & Soos, 2015). The S-L philosophy is deeply rooted in the experiential approach on education, as argued by John Dewey, William Killpatrick (Kraft, 1998) and Jean Piaget (Conrad & Hedin, 1991). Based on the premise that experience is the foundation of education and that in order to understand the world, learners need to interact directly with it (Shellman, 2014), experiential education is a “philosophy that informs many methodologies in which educators purposefully engage with learners in direct experience and focused reflection in order to increase knowledge, develop skills, clarify values, and develop people's capacity to contribute to their communities” (Association for Experiential Education, 2015 apud Bowlby, 2015). If initially the S-L concept was solely and vaguely based on the experiential continuity and interaction principles – cases when the students’ habits and educational experience would influence both current and future educational experiences (Jhonson & Notah, 1999), today’s scientific and socio-economical advances bring forward a wide array of S-L successful implementation guidelines, course frameworks, checklists, positive outcomes proof, evaluation techniques and recommended practices.

Contemporary research categorized S-L as a four-stage process that involves preparation (identifying the community need, establishing a goal and objectives for the S-L project, necessary skills, resources and activities), implementation (and maintaining the connection between the service and academic content), assessment/reflection (evaluating the course, and/or student academic, social or civic learning) and demonstration/celebration (discussing and exhibiting their work) (Jenkins & Sheehey, 2011). The summation of the process basically reveals a service that meets the needs of the community, is coordinated with an educational institution, is integrated into and enhances the core academic curriculum, allows structured time for the students to reflect on the service experience (Billig, 2000) and, finally, it provides the opportunity to openly and publicly demonstrate their project as a form of authentication (Kaye, 2004 apud Jenkins & Sheehey, 2011).

Along these lines, there are numerous positive S-L outcomes that extend from personal to social and academic areas. Thus, a recent S-L comprehensive meta-analysis conducted on over sixty studies by Celio, Durlak and Dymnicki (2011), states that in comparison to control, students participating in S-L programs demonstrate significant gains in attitudes towards self, attitudes toward school and learning, level of civic engagement, social skills and academic performance and benefits regarding self-efficacy, self-esteem, more positive attitudes toward school and education, increased community involvement and gains in social skills relating to leadership and empathy. Moreover, research has further indicated that S-L promotes knowledge and understanding of civic and social issues, increases the levels of awareness and acceptance of diversity in general (Astin & Sax, 1998; Billig et al., 2005; Chang, 2002; Cress, Collier, Reitenauer, & Associates, 2005; Hamm & Houck,1998; apud Jenkins & Sheehey, 2011) and the attitudes towards diversity of the service-beneficiaries (Rusu, Copaci & Soos, 2015).

Consequently, S-L, as a flexible and cost-efficient instructional component, can offer mutual benefits to both the pre-service students and the society while developing crucial pre-requisites of teaching. While conceptually, the literature guidelines can assist us in designing better, more efficient and captivating S-L programs, it is generally acknowledged that individuals unmistakably need to learn from previous recent practice. Therefore, the focus of this paper is on the challenge of introducing S-L instructional strategies in higher academic practice while designing effective, pragmatic S-L programs directed towards reforming education and enhancing pre-service teachers’ experiences.

Aims of the current study

To investigate the recent literature on S-L courses designed to enhance the learning experiences and outcomes of pre-service teachers based on the established research algorithm;

To systematize the findings on core research questions regarding the S-L courses for pre-service teachers;

To outline a best practices profile for designing the S-L course curricula;

To serve as a reference starting point regarding the architecture of future similar S-L programs for pre-service teachers.

Method

In order to outline the best practices in designing a S-L course curricula in higher education for pre-service teachers, the chosen method for this paper was the systematic literature review that follows an algorithm to summarize empirical studies on this particular topic, offers conclusions on the actual scientific knowledge base and reveals unresolved aspects that need further investigations (Cooper, 1998).

In the first planning stage of this paper, an analysis to identify the need of such a review was conducted, followed by the development of a review protocol and outlining of the research questions, as the systemic review process suggests (Judi & Sahari, 2013; Copaci & Rusu, 2015). As stated before, the academic community can benefit from the assistance of existing guidelines, checklists, frameworks or recommended practices in designing a rigorous and methodical S-L program, as well as from the previous recent practice.

In the furtherance of identifying major trends and key points of S-L programs designed for the pre-service teachers, the following research questions guided our research:

1. What is the purpose of the S-L programs?

2. What types of S-L programs are most common in pre-service teachers’ education?

3. What is the hosting environment for the S-L experience?

4. What type of activities do the S-L programs imply?

5. What does the reflection component consist of?

6. What is the average length of the S-L programs?

7. How are the S-L programs evaluated?

The potential relevant studies were identified using several search engines, such as Einformation, ANELiS (http://www.anelis.ro/) and AnelisPlus (http://www.anelisplus.ro/), the latter being programs developed by the Romanian University and Research Institutes Association that offers Romanian university students free mobile access to a wide range of scientific databases, such as: Cambridge Journals, Emerald Management Journals 200, ScienceDirect, Springer Link Journals, Wiley Blackwell, ProQuest Central, OVID LWW High Impact Collection, Oxford University Press, Emerald Group Publishing, American Institute of Physics, Taylor and Francis, EBSCO Academic Search Complete, EBSCO Business Source Complete, SAGE, Thomson ISI and SCOPUS, Reaxys Elsevier, ScienceDirect Freedom Collection Elsevier, Web of Science - Core Collection, Wiley Journals. The protocol applied the following searching keywords: “Service-Learning”, “Pre-Service Teachers” and “Higher education”. The search included the education and sciences disciplines, and as for content, all journal articles, conferences, dissertations and trade publishing articles.

Selection of studies

The inclusion selection criteria were the following:

Studies had to be published in English or Romanian;

Studies had to be published between 31.12.2009 and 1.02.2016;

The publishing criteria had to be peer review journal articles, conference proceedings, dissertations and trade publishing articles;

Studies had to address solely the higher education pre-service students.

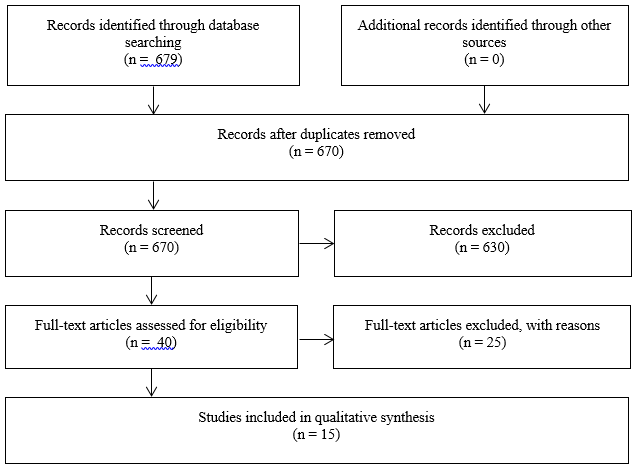

As follows, 679 studies were initially identified in the database, with 670 records remaining after the duplicates were removed. In the screening phase, from a total of 670 papers, 630 records were excluded, leaving 40 potentially satisfactory full-text articles. In the eligibility phase, 25 full-text articles were excluded, leaving a total of 15 eligible studies to be included in the qualitative synthesis. The 25 studies were excluded on the following grounds: missing S-L components (the reflection component, the community service component), the participants being in-service teachers already practicing pedagogy or other un-related student category (nutrition, healthcare, chemistry or not mentioned) that does not necessarily culminate with teaching activities, the service itself being conducted independently of the course’s objectives (i.e. public service), the main focus being other courses for pre-service teachers or other types of education (informal education, non-formal education), unconnected to S-L. The selection process is illustrated in Figure

Results and Discussions

Research question 1: What is the purpose of the S-L programs?

There were various research trends identified regarding the scope of S-L programs, thus emphasizing the adjustable nature of higher education S-L interventions. Nevertheless, all studies included in the current qualitative synthesis are student-centred, focusing mainly on enhancing the pre-service teachers’ authentic learning experience (Green, 2011; Power & Bennet, 2015; Wallace, 2013) and their level of positive attitudes (Chang, Anagnostopoulos, & Omae, 2011; Carringtonm & Selva, 2010; Cone, 2012; Kim, 2012), as well as to ease the transition into practice per se (Coffey, 2011). Table

Research question II: What types of S-L are most common in pre-service teachers’ education?

Table

Research question III: What is the hosting environment for the S-L experience?

All of the studies included in the current qualitative synthesis reported S-L as a field experience combined with previous training by taking part in course activities. The hosting environments varied from common schools (Coffey, 2010; Green, 2011; Trauth-Nare, 2015; Wallace, 2013; Sletto, 2010) to schools placed in distressed neighbourhoods (Conner, 2010), community organizations that serve youth from marginalized groups (Chang, Anagnostopoulos & Omae, 2011), Aboriginal communities (Power & Bennet, 2015), different organizations (Carringtonm & Selva, 2010), community centres (Cone, 2012; Whiteland, 2013), learning centres (Wallace, 2013), homeless shelters (Kim, 2012) and international settings (Naidoo, 2012).

Research question IV: What type of activities do the S-L programs imply?

The S-L activities were categorized into structured, semi-structured and unstructured, based on the existence of training, well-established operational objectives that linked the service with the academic content, following a pre-established curricular plan and/or an academic theme, implementation and evaluation. The majority of S-L activities (9) were structured, based on activity or lesson plans, with trained participants, assisted by guides and operational objectives. 5 studies chose to give more freedom to the pre-service teachers and semi-structured the program while one study approached the S-L in a non-structured, fluid, informal manner (Sletto, 2010). Regarding the S-L activity categories, there is a tendency among recent research to involve pre-service teachers in teaching or literacy activities (7) or partnering and tutoring activities (4) whereas some chose to extend the service through art – music teaching (Power, 2013) and collage-making (Whiteland, 2013) or designing and conducting pedagogical activities (2), mostly found in structured instances. Table

Research question V: What does the reflection component of S-L programs consist of?

Reflection appears to be an imperative component of the S-L due to the fact that it links the S-L experience to the filter of academic content (Heffernan, 2001). Almost half (7) of the studies analysed chose a reflection journal as their main reflection component, while others (4) decided to involve technology as being more suited for the “digital-native” (Prensky, 2001) student: blogging (Green, 2011), weekly logs (Iverson & James, 2010; Sletto, 2010) or digital stories (Power & Bennet, 2015), as seen in Table

Research question VI: What is the average length of the S-L programs?

As shown in Table

Research question VII: How are the S-L programs evaluated?

Table

Conclusions

The current paper used a systematic review protocol to analyse the latest research on the S-L programs (i.e. 15 studies from 2010-2016 met the inclusion criteria). The results reflect the aims of the S-L programs, the most common types of S-L in pre-service teachers’ education, types of hosting environment for the S-L service component, various types and categories of S-L activities, most frequent reflection methods and program lengths, and a wide array of final course evaluation alternatives. The investigated literature reveals an on-going preference for embedding the S-L program in university course curricula (i.e. 12 out of 15 scholars designed this programs in this manner). Another highlight of this review is the predilection to use structured S-L approaches, as 9 out of 15 studies mentioned pre-service training, structured activities guided by operational objectives that link the academic content to the community service, whereas only 5 studies gave more freedom to the service participants and semi-structured their activities. Since the studies included in the review only addressed pre-service teachers, the majority of S-L activities (7) focused on teaching and literacy together with previously designing a lesson plan on a certain curricular theme, followed by tutoring (4) and assisting children with various school tasks or homework. Moreover, the one semester approach seems to be the preferred length for delivering S-L programs, especially in the cases when the program is embedded in course curricula.

One of the most important components of the S-L programs, the reflection, was mainly designed in the form of reflection journals with 7 mentions and 4 online reflection logs or blog posts after each encounter with the S-L beneficiaries. Regarding the evaluation of such programs, the results indicate that a final course official writing task is still the preferred method, coupled with exit interviews – both with 4 mentions. On the contrary, 3 studies chose not to officially evaluate the students and only one study made use of alternative, modern means of evaluation such as posters, short narratives and photography. Wistfully, only one program out of the total 15, included a final celebration in the form of a class poster fair (Iverson & James, 2010), following the guidelines (Jenkins & Sheehey, 2011) and offering the students their much deserved demonstration moment as a form of validation. Little or no information is offered about the course credits system. Our findings may serve as a premise for designing better, more efficient S-L programs when combined with existing guidelines and checklists, taking the tailor-made approach into consideration, thus suitable for the needs of every pre-service teacher.

References

- Billing, S. H. (2000). Research on K-12 School-Based Service-Learning: The Evidence Builds. Phi Delta Kappan, 81, 658-664.

- Bowlby, J. L. (2015). A Look At Experiential Education In Preparing High School Students For The Future. Comparative International Education, 8530A, 1-11.

- Carringtonm S. & Selva, G. (2010). Critical social theory and transformative learning: evidence in pre‐service teachers’ service‐learning reflection logs. Higher Education Research & Development, 29(1), 45-57.

- Celio, C. I., Durlak, J., Dymnicki, A. (2011). A Meta-analysis of the Impact of Service-Learning on Students. Journal of Experiential Education, 34(2), 164-181.

- Chang, S., Anagnostopoulos, D. & Omae, H. (2011). The Multidimensionality of Multicultural Service Learning: The Variable Effects of Social Identity, Context and Pedagogy on Pre-Service Teachers' Learning. Teaching and Teacher Education: An International Journal of Research and Studies, 27(7), 1078-1089.

- Coffey, H. (2010). “They taught me”: The benefits of early community-based field experiences in teacher education. Teaching and Teacher Education, 26(2), 335-342.

- Cone, N. (2012). The Effects of Community-Based Service Learning on Preservice Teachers’ Beliefs About the Characteristics of Effective Science Teachers of Diverse Students. Journal of Science Teacher Education, 23, 889-907.

- Conner, J. (2010). Learning to unlearn: How a service-learning project can help teacher candidates to reframe urban students. Teaching and Teacher Education, 26(5), 1170-1177.

- Conrad, D. & Hedin, D. (1991). School-based community service: What we know from research and theory. Phi Delta Kappan, 72, 743-749.

- Cooper, H. M. (1998). Synthesizing Research: A Guide for Literature Reviews. (Vol. 2). Sage.

- Green, A. M., Kent, A. M., Lewis, J., Feldman, P., Motley, M. R., Baggett, P. V., Shaw, E. L., Byrd, K. & Simpson, J. (2011). Experiences of Elementary Pre-service Teachers in an Urban Summer Enrichment Program. Western Journal of Black Studies, 35(4), 227-239.

- Heffernan, K. (2001). Service-Learning in Higher Education. Journal of Contemporary Water Research and Education, 119(1), 2-8.

- Iverson, S. V. & James, J. H. (2010). Becoming “Effective” Citizens? Change-Oriented Service in a Teacher Education Program. Innovative Higher Education, 35(1), 19-35.

- Jenkins, A. & Sheehey, P. (2011). A Checklist for Implementing Service-Learning in Higher Education. Journal of Community Engagement and Scholarship, 4(2), 52-60.

- Kraft, J. R. (1998). Service Learning: An Introduction To Its Theory, Practice, And Effects. Advances in Education Research, 3, 13-29.

- Johnson, A. M. & Notah, D. J. (1999). Service Learning: History, Literature Review, and a Pilot Study of Eighth Graders. The Elementary School Journal, 99(5), 454-466.

- Kim, J. (2013). Confronting Invisibility: Early Childhood Pre-service Teachers’ Beliefs Toward Homeless Children. Early Childhood Education Journal, 41, 161-169.

- Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, The PRISMA Group (2009). Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med 6(7): e1000097. doi:

- Naidoo, L. (2012). Refugee action support: Crossing borders in preparing pre-service teachers for literacy teaching in secondary schools in Greater Western Sydney. International Journal of Pedagogies and Learning, 7(3), 266-274.

- Power, A. (2013). Developing the music pre-service teacher through international service learning. Australian Journal of Music Education, 2, 64-70.

- Power, A. & Bennett, D. (2015). Moments of becoming: experiences of embodied connection to place in arts-based service learning in Australia. Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education, 43(2), 156-168.

- Prensky, M. (2001). Digital Natives, Digital Immigrants. On the Horizon, 9 (5), Retrieved on 12.02.16 from: http://www.marcprensky.com/writing/Prensky%20-%20Digital%20Natives,%20Digital%20Immigrants%20-%20Part1.pdf

- Rusu, A. S., Bencic, A. & Hodor, T. I. (2014). Service-Learning programs for Romanian students – an analysis of the international programs and ideas of implementation. Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences, 142, 154-161.

- Rusu, A. S., Copaci, I. A., & Soos, A. (2015). The Impact of Service-Learning on Improving Students’ Teacher Training: Testing the Efficiency of a Tutoring Program in Increasing Future Teachers’ Civic Attitudes, Skills and Self-Efficacy. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 203, 75-83.

- Shellman, A. (2014). Empowerment and Experiential Education: A State of Knowledge Paper. Journal Of Experiential Education, 37(1), 18-30.

- Sletto, B. (2010). Educating Reflective Practitioners: Learning to Embrace the Unexpected through Service Learning. Journal of Planning Education and Research, 29(4), 403-415.

- Trauth-Nare, A. (2015). Influence of an Intensive, Field-Based Life Science Course on Preservice Teachers’ Self-Efficacy for Environmental Science Teaching. Journal of Science Teacher Education, 26(5), 497-519.

- Wallace, C. S. (2013). Promoting Shifts in Preservice Science Teachers’ Thinking through Teaching and Action Research in Informal Science Settings. Journal of Science Teacher Education, 24(5), 811-832.

- Whiteland, S. (2013). Picture Pals: An Intergenerational Service-Learning Art Project. Art Education, 66(6), 20-26.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

22 December 2016

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-017-4

Publisher

Future Academy

Volume

18

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-672

Subjects

Teacher, teacher training, teaching skills, teaching techniques, special education, children with special needs

Cite this article as:

Copaci*, I. A., & Rusu, A. S. (2016). Trends in Higher Education Service-Learning Courses for Pre-Service Teachers: A Systematic Review. In V. Chis, & I. Albulescu (Eds.), Education, Reflection, Development - ERD 2016, vol 18. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 1-11). Future Academy. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2016.12.1