Abstract

This study examines the relationship between religiosity, training reaction and motivation to transfer. Structured equation modelling is conducted on survey data from 306 public sector employees in Malaysia. The result of this study highlight the importance of religiosity as a trainee characteristic factor that can influence employee reaction toward the training program, and ultimately demonstrate positive intention to transfer the training outcomes in the workplace. The findings of this study is very important because the relationship between religiosity, reaction and motivation to transfer has not been examined in the literature, particularly the relationship between religiosity and reaction, and the role of reaction as a mediator between religiosity and motivation to transfer.

Keywords: Training ReactionPublic SectorMalaysia

1. Introduction

One of the criteria to evaluate training effectiveness is reaction. Reaction refers to trainees’ affective and utility responses to the training program (Arthur, Bennett, Edens & Bell, 2003). Affective response is the extent to which a trainee was satisfied with different components of the training such as instructional materials, method of delivery and training facilities. Utility reaction refers to trainees’ subjective evaluation of whether or not the content of the training program is useful for their respective jobs (Alliger, Tannenbaum, Bennett & Traver, 1998; Rowold, 2007).

Reaction has received significant research attention, generally focused on exploring the factors that influence it. A range of factors have been identified by previous studies including the trainees’ motivation to learn (Pilati & Borges-Andrade, 2008), commitment (Seyler, Holton, Bates, Burnett & Carvalho, 1998), personality (Colquitt, LePine & Noe, 2000), demography such as gender, age, work experience, education level, job level (Ozturan & Kutlu, 2010), perceived practical relevant (Liebermann & Hoffmann, 2008) and perceived content validity (Bhatti & Kaur, 2010). These findings are very important, which can enhance organizations understanding about the factors that influence reaction.

Another important factor, which could has influence on reaction is religiosity. Religiosity can be described as the employee commitment to the empirical and theoretical fundamentals of the religion (Al-Goaib, 2003). Previous studies revealed that religiosity can facilitate employees’ feelings (Abdel-Khalek, 2010; Kandaswamy, 2007), work attitude and behavior (Achour, Grine, Mohd Nor & Mohd Yusoff, 2015; Tiliouine & Belgoumidi, 2009). Therefore, this study posits that the trainees’ commitment to the empirical and theoretical fundamentals of the religion could affect their affective and utility responses to the training program. However, such relationship has not yet empirically tested in the literature.

Another important issue that has received attention by previous training researchers is the consequences of reaction, particularly on employees. A number of studies demonstrate that reaction has relationship with motivation to transfer (Gegenfurtner, Veermans, Festner & Gruber, 2009; Liebermann & Hoffmann, 2008). In other word, previous studies argue that the trainees’ affective and utility responses to the training program can influence their intention to apply the learned knowledge and skills in the workplace. However, the existing findings have been generated based on employees’ perspective from Western context. According to Rees and Johari (2010), the findings that have been developed in the Western context, are not necessarily applicable to Asian countries. One explanation for this is the cultural differences between Western and Asian countries (Hofstede & Hodstede, 2005).

This study will address the gaps identified earlier. This study aims to make four contributions. First, exploring the relationship between religiosity and reaction can expand our understanding about the effect of another aspect of trainee characteristic on reaction. Such effort has been regarded as an important research direction by recent training scholars such as Liebermann and Hoffmann (2008) and Bhatti and Kaur (2010). Second, studying the relationship between religiosity and reaction can provide empirical evidence to the notion, which has been hypothesized by previous studies, that trainee characteristic (in this study refers to religiosity) to have a direct influence on reaction (Lim & Morris, 2006). Third, there is a growing recommendation to test the role of reaction as a mediator between the factors that influence reaction and motivation to transfer (Gegenfurtner et al., 2009; Bhatti & Kaur, 2010). Such effort can expand the existing knowledge that mostly regard reaction as direct predictors of training criteria (Morgan & Casper, 2000). This study provides empirical evidence about the role of reaction as a mediator in the relationship between religiosity and motivation to transfer. Fourth, the findings of this study is unique because the conceptual framework has been examined in the context of public sector organizations. Previous studies have mostly been conducted in private sector organizations. In previous studies evidence has been presented showing that organizational climate can influence trainees’ affective and utility responses to the training program (Colquitt et al., 2000). As public and private sector organizations are significantly difference in term of climate (e.g., organizational goals and systems, work values, work motivation (Buelens & Broeck, 2007), the findings of this study can enrich the understanding about religiosity, reaction and motivation to transfer issues in different context, specifically the public sector organizations in Malaysia (a developing country at Southeast Asia).

2. Literature review

2.1 The relationship between religiosity and reaction

Prior research suggests employees who have commitment to the empirical and theoretical fundamentals of the religion (religiosity) will feel satisfaction with their life, job and family (Achour et al., 2015; Tiliouine & Belgoumidi, 2009). Employees also can minimize the negative feelings such as anxiety (Abdel-Khalek, 2010) and stress (Kandaswamy, 2007), as a result of religiosity. The previous findings prove that religiosity can play an important role on individual feeling and emotion. As the term of reaction is the same as measuring the feelings (Kirkpatrick, 1998), this study hypothesized that the religiosity will be positively related to trainees’ affective and utility responses to the training program. Therefore, the following hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 1: Religiosity is positively related to reaction

2.2 The relationship between reaction and motivation to transfer

Empirical studies among sample from various industry such as motor vehicle dealerships (Warr, Allan & Birdi, 1999), banking (Liebermann & Hoffmann, 2008), Petrochemical (Seyler et al., 1998), and private university (Burke, 1997) confirm a significant relationship between reaction and motivation to transfer. In fact, reaction has been found as the main predictor for motivation to transfer (Liebermann & Hoffmann, 2008). These findings suggest that trainees who have positive reaction to the training program show high intention to transfer the learned knowledge and skills to their workplace following the training. Accordingly, the present study presumes that the employees of public sector organizations in Malaysia may engender greater motivation to transfer as a result of their positive reaction to the training program they have attended. Therefore, the following hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 2: Reaction is positively related to motivation to transfer

2.3 Reaction as a mediator

As previously discussed, this study propose a positive relationship between religiosity and reaction (Hypothesis 1). In addition, this study propose that reaction positively relates to motivation to transfer (Hypothesis 2). Both hypotheses a possible indirect effect between religiosity and motivation to transfer (Zumrah, 2015; Zumrah & Boyle, 2015). Thus, this study propose that reaction could be a mediator between religiosity and motivation to transfer.

Hypothesis 3: Reaction is a mediator between the religiosity and motivation to transfer

Based on the previous hypotheses, below is a research framework of this study (see Figure

3. Methodology

3.1 Sample

This study was conducted in a public sector organization in Malaysia. New employees (have worked in the public sector within six months to one year), who attended a ‘Mind Transformation Program’ have participated in this study. The data were collected through questionnaire. A total of 308 questionnaires was collected. However, only 306 questionnaires contained complete data. The other 2 questionnaires have been eliminated due to incomplete (few questions have not been answered by respondents).

Among the respondents, 63 percent (

3.2 Measures

This study used previously published measures. All measures were assessed using a five-point Likert-type scale (1 = strongly disagree; 2 = disagree; 3 = neutral; 4 = agree; 5 = strongly agree).

Religiosity was measured using 10 items developed by Achour, Grine, Mohd Nor and Mohd Yusoff (2015). An example of the items is ‘Religion is important to me because it helps me to cope with life events’. Cronbach’s alpha for the scale in this study was 0.94.

Reaction was measured using three items developed by Marler, Liang and Dulebohn (2006). An example of the items is ‘The training sessions meet my expectations’. Cronbach’s alpha for this scales in this study was 0.86.

Motivation to transfer was measured using four items developed by Baharim (2008). An example of the items is ‘I will put into practice what I have learned from the training to the workplace’. Cronbach’s alpha for this scales in this study was 0.94.

4. Analysis results

The data of this study have been analyzed through structural equation modeling technique. As recommended by Anderson and Gerbing (1988), this study estimated a measurement model using a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) prior to examining the structural model relationships.

The measurement model that included all items showed a good fit. For example, the value of chi-square (χ2) / degrees of freedom (

Based on Table

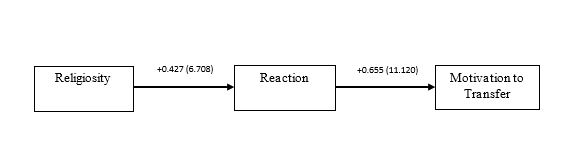

After estimating the measurement model with a confirmatory factor analysis, the second stage of analysis involved estimating the proposed relationships. As demonstrated in Table

Notes: Figures are factor loadings followed by critical ration value. The critical ratio value indicates the significant level of factor loading. The minimum critical ratio value of 1.960 is required for the factor loading to be significant (Byrne 2010). ***p<0.001.

5. Discussion

The result from data analysis has confirm the first hypothesis of this study by demonstrating a positive and significant relationship between religiosity and reaction. The result suggest that the employees’ religiosity value (committed to the empirical and theoretical fundamentals of the religion) can influence their affective and utility responses to the training program. This finding is an important outcome that has not been empirically determined previously in the training literature. This finding also responds to recent researchers suggestion to identify further factors that have an impact on the trainee reaction (Liebermann & Hoffmann, 2008; Bhatti & Kaur, 2010), and helps clarify and support previous arguments indicating that the trainee reaction to the training program can be influence by the trainee characteristic (Lim & Morris, 2006).

The result from data analysis also has provide support to the second hypothesis of this study by demonstrating a positive and significant relationship between reaction and motivation to transfer. This result is in line with the results of previous empirical work in private sector context (Burke, 1997; Seyler et al., 1998; Warr et al., 1999; Liebermann & Hoffmann, 2008). The result suggest that when employees of public sector organizations in Malaysia shows positive reaction to the training program, they will demonstrate a positive intention to apply the knowledge and skill that they learned in training to their workplace, following the training program. This may result from the nature of employees in public sector in Malaysia, who emphasize on the norm of reciprocity in which people respond to each other in kind – returning benefits for benefits. Previous study that has been conducted in similar context of this study reveals that when employees perceived organizational support, they have apply the learned knowledge and skills in the workplace, which, in turn increase their job performance (Zumrah, 2015).

The result from data analysis further confirm the third hypothesis of this study, which shows that reaction has essential role as a mediator in the relationship between religiosity and motivation to transfer. The significant relationship between religiosity – reaction – motivation to transfer is an important finding that has not been empirically determined previously in the training literature. Although such relationship is limited to the specific context of the public sector in Malaysia, this study highlight religiosity as an important factor that can influence employees reaction toward the training program, and ultimately their motivation to transfer the training outcomes in the workplace following the training.

6. Implication of the study

This study provide guidance to training practitioners (e.g., training consultant company) wishing to enhance a positive training reaction of public sector employees in Malaysia. A significant relationship between religiosity and reaction indicates that the importance of religion elements to be include in the training program when conducting training to public sector employees in Malaysia. As the majority of public sector employees in Malaysia are Muslim, example of religion element that can be implement during the training program is reciting

The finding of this study underline the importance for management of public sector organization in Malaysia to improve employee reaction toward the training program because this study suggest that when employees shows positive reaction to the training program, they will demonstrate a positive intention to apply the knowledge and skill that they learned in training to their workplace. The management team might do this by ensuring the training content is relevant to employees’ current job, and can be practically implement at the employee workplace. Previous research demonstrates that these initiatives have play a greater role in promoting positive reaction of employees toward the training program (Liebermann & Hoffmann, 2008; Bhatti & Kaur, 2010).

7. Limitations and suggestions for future study

First, this study is limited to a single context, which is employees of the public sector in Malaysia. Future research is encouraged to validate the proposed framework of this study that include religiosity, motivation to learn and motivation to transfer, in another context. It is due to every country is unique in terms of environmental characteristics and culture.

Second, this study only examine the effect of religiosity on reaction. Future study may expand the literature by exploring the effect of other aspect of trainee characteristics on reaction. This suggestion is in line with other reseachers who continuously suggest to further identify the factors that have an impact on the trainee reaction (Liebermann & Hoffmann, 2008; Bhatti & Kaur, 2010).

Acknowledgement

This paper is based on the research that funded by the Fundamental Research Grant Scheme (FRGS), Ministry of Higher Education Malaysia

References

- Abdel-Khalek, A. M. (2010). Religiosity, happiness, health, and psychopathology in a probability sample of Muslim adolescents. Mental Health, Religion, and Culture, 10, 571–583.

- Achour, M., Grine., Mohd Nor,. & Mohd Yusoff. (2015). Measuring religiosity and its effects on personal well-being: A case study of Muslim female academicians in Malaysia. Journal of Religion and Health, 54(3), 984-997.

- Al-Goaib, S. (2003). Religiosity and social conformity of university students: An analytical study applied at King Saoud University. Arts Journal of King Saoud University, 16(1), 51–99.

- Alliger, M. G., Tannenbaum, S. I., Bennett, W., & Traver, H. (1998). A meta-analysis of the relations among training criteria. United States Air Force Research Laboratory Report.

- Anderson, J.C., & Gerbing, D.W. (1988). Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychological Bulletin, 103, 411–423.

- Arthur, W., Bennett, W., Edens, P., & Bell, S. (2003). Effectiveness of training in organizations: A meta-analysis of design and evaluation features. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(2), 234-244.

- Baharim, S. B. (2008). The influence of knowledge sharing on motivation to transfer training: A Malaysian public sector context. Victoria University, Melbourne

- Bhatti, M. A., & Kaur, S. (2010). The role of individual and training design factors on training transfer. Journal of European Industrial Training, 34(7), 656-672.

- Browne, M. W., & Cudeck, R. (1993). Alternative ways of assessing model fit. In K. A. Bollen & J. S. Long (Eds.), Testing structural equation models (pp. 136-162). Newsbury Park, CA: Sage.

- Buelens, M., & Broeck, H. V. d. (2007). An analysis of differences in work motivation between public and private sector organizations. Journal of Public Administration Review, 67(1), 65-74.

- Burke, L. A. (1997). Improving positive transfer: A test of relapse prevention training on transfer outcomes. Human Resource Development Quarterly, 8(2), 115-128.

- Byrne, B. M. (2010). Structural equation modeling with AMOS: Basic concepts, applications, and programming (2nd ed.). New York: Routledge.

- Carlson, M., & Mulaik, S. (1993). Trait ratings from descriptions of behavior as mediated by components of meaning. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 28, 111–159.

- Chand, M. (2010). The impact of HRM practices on service quality, customer satisfaction and performance in the Indian hotel industry. International Journal of Human Resource Management, 21(4), 551-566.

- Colquitt, J., LePine, J., & Noe, R. (2000). Toward an integrative theory of training motivation: A meta-analytic path analysis of 20 years of research. Journal of Applied Psychology, 85(5), 678-707.

- Gegenfurtner, A., Veermans, K., Festner, D., & Gruber, H. (2009). Integrative literature review: Motivation to transfer training: An integrative literature review. Journal of Human Resource Development Review, 8(3), 403-423.

- Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2010). Multivariate data analysis: A global perspective (7th ed.). Boston: Pearson.

- Hofstede, G., & Hofstede, G. J. (2005). Cultures and organizations: Software of the mind. New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Kandaswamy, D. (2007). Islamic ways of managing stress. Seven ways to deal with stress. Retrieved September 24, 2009. http://www.mindtools.com/stress/RelaxationTechniques/IntroPage.ht

- Kirkpatrick, D. L. (1998). Evaluating Training Programs (2nd ed.). San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler.

- Liebermann, S., & Hoffmann, S. (2008). The impact of practical relevance on training transfer: Evidence from a service quality training program for German bank clerks. International Journal of Training and Development, 12(2), 74-86.

- Lim, D., & Morris, M. (2006). Influence of trainee characteristics, instructional satisfaction, and organizational climate on perceived learning and training transfer. Journal of Human Resource Development Quarterly, 17(1), 85-115.

- Marler, J. H., Liang, X., & Dulebohn, J. H. (2006). Training and effective employee information technology use. Journal of Management, 32(5), 721-743.

- Morgan, R. B., & Casper, W. J. (2000). Examining the factor structure of participant reactions to training: A multidimensional approach. Human Resource Development Quarterly, 11(3), 301-317.

- Pilati, R., & Borges-Andrade, J. E. (2008). Affective predictors of the effectiveness of training moderated by the cognitive complexity of expected competencies. International Journal of Training and Development, 12(4), 226-237.

- Rees, C. J., & Johari, H. (2010). Senior managers' perceptions of the HRM function during times of strategic organizational change: Case study evidence from a public sector banking institution in Malaysia. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 23(5), 517-536.

- Rowold, J. (2007). Individual influences on knowledge acquisition in a call center training context in Germany. International Journal of Training and Development, 11(1), 21-34.

- Seyler, D., Holton III, E., Bates, R., Burnett, M., & Carvalho, M. (1998). Factors affecting motivation to transfer training. International Journal of Training and Development, 2(1), 2-16.

- Tabachnick, B. G., & Fidell, L. S. (2007). Using multivariate statistics (5th ed.). Boston: Pearson.

- Tiliouine, H., & Belgoumidi, A. (2009). An exploratory study of religiosity, meaning in life and subjective wellbeing in Muslim students from Algeria. Applied Research Quality Life, 4, 109–127.

- Ozturan, M., & Kutlu, B. (2010). Employee satisfaction of corporate e-training programs. Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences, 2(2), 5561-5565.

- Warr, P., Allan, C., & Birdi, K. (1999). Predicting three levels of training outcome. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 72(3), 351-375.

- Williams, L. J., Vandenberg, R. J., & Edwards, J. R. (2009). Structural equation modeling in management research: A guide for improved analysis. The Academy of Management Annals, 3(1), 543-604.

- Zumrah, A. R. (2015). Examining the relationship between perceived organizational support, transfer of training and service quality in the Malaysian public sector. European Journal of Training and Development, 39(2), 143-160.

- Zumrah, A. R., & Boyle, S. (2015) The effects of perceived organizational support and job satisfaction on transfer of training. Personnel Review, 44(2), 236 – 254.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

22 November 2016

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-015-0

Publisher

Future Academy

Volume

16

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-919

Subjects

Education, educational psychology, counselling psychology

Cite this article as:

Zumrah, A. R., Khalid, M. Y., Ali, K., & Mokhtar, A. N. (2016). Examine The Factor That Influence Training Reaction, And Its Consequence On Employee. In Z. Bekirogullari, M. Y. Minas, & R. X. Thambusamy (Eds.), ICEEPSY 2016: Education and Educational Psychology, vol 16. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 427-435). Future Academy. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2016.11.44