Abstract

The present study seeks to understand the relationship between organizational commitment and its components with turnover intention among generation Y working in Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs) in Malaysia. Self-administered questionnaires with 18 items on organizational commitment construct and 4 items on turnover intention construct were distributed to the randomly-selected sample. A measurement model and structural model was later constructed using AMOS. Results indicate that the measurement model to test hypotheses was valid and reliable. However, based on the structural model constructed, no relationship between organizational commitment and turnover intention was indicated. There is also no relationship between affective commitment and turnover intention as well as normative commitment. Only continuance commitment significantly affected turnover intention. The finding is supported by few arguments regarding the characteristics of generation Y and the nature of SMEs industries.

Keywords: Organizational commitment; turnover intentionSMEs

Introduction

Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs) in Malaysia contribute 32 percent of total Gross Domestic Product (GDP) and cover 99.2 percent of the total business established with more than 500,000 enterprises in many different sectors (Tenth Malaysia Plan, 2012). However, according to the World Bank, there is high labour turnover rate among SMEs in developing countries and Malaysia recorded one of the highest turnovers, around 19 percent in small enterprises and 22 percent of medium enterprises (Batra & Tan, 2003).

High turnover has a devastating impact on the organization as it not only leads to a decrease in productivity, service delivery and knowledge transfer but also causes difficulties in retaining and attracting talent in an organization especially among the younger generation (Mohd Hanif & Chia, 2013). Direct and indirect costs are involved in high labor turnover. When employees leave the organization, the direct cost incurred refers to replacement cost, transition cost and rehiring cost. Meanwhile, the indirect cost is related to the cost caused by employee absence or transition such as loss of production, reduced performance level, unnecessary overtime and low morale (Asian Institute of Finance, 2013).

The purpose of this study is to investigate the relationship between organizational commitment on turnover intention among Generation Y (Gen Y). Research has established a significant relationship between organizational commitment and turnover intention (Feris & Aranya, 1983; Steers, 1977; Wiener & Vardi, 1980) concluding that organizational commitment is important in preventing turnover intention. The study will focus on Gen Y as they believe in the benefits of multitasking and in quality over quantity of work time. Additionally, they like to take on more challenging work (Lloyd, 2007). These traits are causing them to limit their commitment to a single, particular organization. Based on data from the Asian Institute of Finance (2013), only 23 percent of Gen Y workers have the intention to work more than 5 years in their current organization.

Literature Review

Organizational commitment can be defined as “multidimensional in nature, involving an employee’s loyalty to the organization, willingness to exert effort on behalf of the organization, degree of goal and value congruency with the organization, and desire to maintain membership” (Bateman & Strassers, 1984). It premises employees' association and involvement with the organization (Porter et. al., 1974). According to Meyer and Allen (1991), organizational commitment is a psychological state that that binds employees and the organization and it can affect employee decision whether to continue membership in the organization.

Turnover intention is a mental decision employees make either to stay or leave the organization (Jacobs & Roodt, 2007). It is connected to turnover behavior (Boles et. al., 2007) and serves as an immediate indicator to actual turnover (Hom & Griffeth, 1991). Turnover can be described as the “individual movement across the membership boundary of an organization” (Price, 2001). However, research by Souza-Poza (2007) shows that more than 40 percent turnover had no turnover intention (not announced) while only 25 percent turnover intention led to actual turnover. Thus, it is crucial for organizations to have good talent retention programs.

The influence of organizational commitment on turnover intention has been studied previously and the findings show that these variables have significant effect on turnover intention (Karsh, Booske, & Sainfort, 2005; Kuen et. al., 2010). According to Porter (1974), employees with lower levels of commitment were more likely to leave the organization than their colleagues. Thus, it is expected that:

H1: Organizational commitment has a significant relationship with turnover intention

There are three dimensions in organizational commitment that characterize employees’ relationship with the organization namely affective, continuance and normative commitment. Affective commitment is related to the emotional attachment employees feel towards the organization and the way they identify themselves with it (Mowday et. al., 1979). Meanwhile, continuance commitment refers to the employees’ inclination to stay in the organization for various reasons (Reichers, 1985; Meyer & Allen, 1997). Normative commitment is linked to the moral nature of obligation to stay and part of the generalized value of loyalty and duty (Bolon, 1993; Meyer & Allen, 1991). Thus, it is expected that:

H1a.Affective commitment has a significant relationship with turnover intention

H1b.Continuance commitment has a significant relationship with turnover intention

H1c.Normative commitment has a significant relationship with turnover intention

Methodology

The study use self-administered questionnaires to capture information on organizational commitment and turnover intention. Enterprises located in Kuala Lumpur, Selangor and Johor were randomly chosen for this research because most SMEs are concentrated in these 3 states. (SMECorp, 2013). Of the total questionnaires distributed, 158 questionnaires were returned with a response rate of 41 percent. As the study focuses on Gen Y, only employees aged 16 to 37 years old were given questionnaires (Robbins et al., 2011).

Organizational commitment was assessed using an instrument from Meyer, Allen & Smith (1993). The 18 items with 6 items per construct were rated on a six-point Likert scale (1 = Strongly disagree, 6 = strongly agree). The reliability analysis gave Cronbach’s alpha value 0.845 which ranged from 0.687 to 0.87. For turnover intention, the instrument was adapted from Porter et. al. (1974) which has 4 items and the Cronbach’s alpha was 0.856. All items were rated using a six-point Likert scale. During the survey, structured bi-lingual questionnaires (Bahasa Malaysia and English) were distributed. The Malay version of the items were developed using standard back-translation techniques (Breslin, 1970).

Results

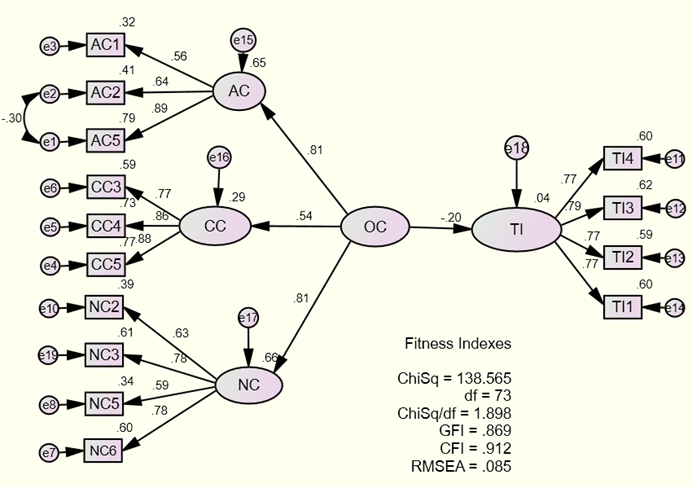

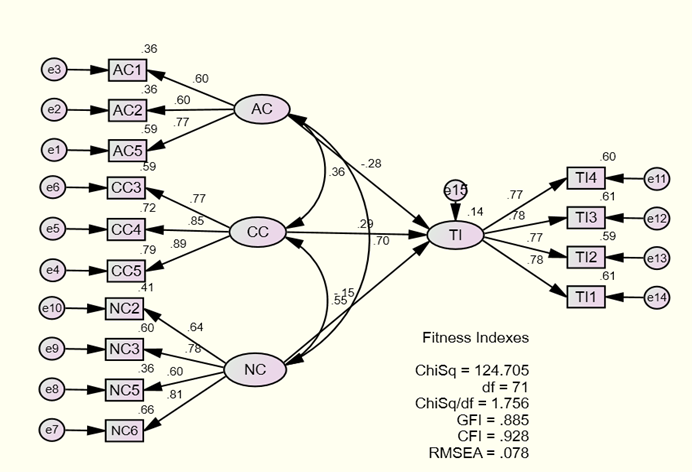

The confirmatory factor analysis was conducted using AMOS in which two models were constructed in order to test the hypothesis. Model 1 assessed the relationship between the two latent constructs, organizational commitment and turnover intention. Meanwhile, Model 2 assessed the relationship between three dimensions of organizational commitment and turnover intention. Table

Reliability of the model can be assessed using three criteria; internal reliability, construct reliability and average variance extracted (AVE). Internal reliability is achieved when Cronbach’s Alpha value is more than 0.60 (Hair, 2010). Construct reliability (CR) measure the reliability and internal consistency of the constructs. The cut-off value for CR is 0.60 (Zainudin, 2012). Meanwhile, AVE is the percentage of variance explained by the items in a construct and the cut-off value is 0.50 (Bagozzi and Yi, 1988).

For model 1, the internal reliability (Cronbach alpha), construct reliability and average variance extracted is presented in table

Figure

For model 2, the internal reliability (Cronbach alpha), construct reliability (CR) and average variance extracted (AVE) is presented in table

Based on the structural model 2 in figure

Conclusion

This study found that organizational commitment has no significant relationship with turnover intention despite various researches that supported the relationship between these two latent constructs. It is not consistent with findings from other research (Karsh et. al., 2005; Porter et. al., 1974). The conflicted results might be due to different groups of respondents. Gen Y have a different workplace attitudes and they willing to change organizations for better opportunities and appreciation. However, this does not mean that they do not give great commitment to the current organization (Cruz, 2007). Advancement of technology makes work more efficient and effective but at the same time opens a vast opportunity for Gen Y to acquire knowledge of better conditions that suit their individual interests, that might be offered in other organizations. The transition to other organizations is much easier and less costly for workers.

The potential fluidity in career is one of the unique traits of Gen Y in which changing work and organizations is affected by their expectations and values (New Paradigm, 2006). Gen Y continuously look for feedback and advice from their superiors and expect continuous direction from them regarding their performance (BSG Concours, 2007). Knowledge transfer plays a vital role in career advancement and they take failure as the opportunity to improve their performance in the future (Blain, 2008). Thus, they do not see changing organizations as part of failure but rather a challenge that they seek.

Continuance commitment is correlated with turnover intention based on the assumption of financial exchange between employees and their organization (Meyer et. al., 2002). The nature of work in SMEs where Gen Y view their job only as a means of survival which they will quit at the opportunity of better compensation. Employees stay because of the related and other costs if they leave (Allen, 2003). Thus, in conclusion, the turnover intention among Gen Y in SMEs is not affected by the commitment they give to their employers and the only reason for them to have an intention to leave is to survive.

References

- Allen, N (2003). Organizational Commitment in the Military: A Discussion of Theory and Practice. Military Psychology, 15, 237-253.

- Asian Institute of Finance (2014). Managing Gen Y in the workplace. Asian Link, 15.

- Bagozzi, R.P. and Yi, Y. (1988). On the evaluation of structural equation models. Journaof the academy of marketing science. 16(1), 74-94.

- Bateman, T. and Strasser, S. (1984). A longitudinal analysis of the antecedents of organizational commitment. Academy of Management Journal, 27, 95‐112.

- Batra, G. & Tan H. (2003). SME Technical Efficiency and Its Correlates: Cross-National Evidence and Policy Implications, World Bank Institute Working Paper.

- Blain, Alicia. 2008. ―The Millennial Tidal Wave: Five Elements That Will Change TheWorkplace of Tomorrow. Journal of the Quality Assurance Institute, 22(2) 11-13.

- Boles, J., Madupalli, R., Rutherford, B. & Wood, J. A. (2007). The relationship of facets of salesperson job satisfaction with affective organizational commitment. Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing. 22 (5), 311–321.

- Bolon, D.S. (1997). Organizational Citizenship Behavior Among Hospital Employees: A Multidimensional Analysis Involving job Satisfaction and Organizational Commitment”. Hospital & Health Services Administration, 42( 2), 221-241.

- Breslin, R. W. (1970). Back-translation for cross-cultural research. Cross-Cultural Psychology, 1, 185–216.

- Browne, M. W., & Cudeck, R. (1993). Alternative ways of assessing model fit. In K. A. Bollen & J. S. Long (Eds.), Testing structural equation models (pp. 136-162). Newsbury Park, CA: Sage.

- BSG Concours. (2007). ―Engaging Today’s Young Employees. Results Research Project YE.

- Cruz, C. S. (2007). Gen Y: How Boomer Babies are Changing the Workplace. Hawaii Business, 52 (11), 38.

- Economic Planning Unit (2010a). The Tenth Malaysia Plan 2011-2015. Malaysia

- Ferris, K.R. and Aranya, N. (1983). A comparison of two organizational commitment scales. Personnel Psychology, 36, 87‐98.

- Hair, J.F., Black, W.C., Rabin, B.J., & Anderson, R.E. (2010). Multivariate Data Analaysis (7th Ed.) Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

- Hom, P. W., Katerberg, R., &Hulin, C. L. (1979).A comparative examination of three approaches to the prediction of turnover. Joumal of Applied Psychology, 64, 280-290.

- Jacobs, E. & Roodt, G. (2007).The development of a knowledge sharing construct to predict turnover intentions. Aslib Proceedings: New Information Perspectives, 59(3), 229-248.

- Karsh, B., Booske, B.C. and Sainfort, F. (2005). Job and organizational determinants of nursing home employee commitment, job satisfaction and intent to turnover. Ergonomics, 48, 1260‐81.

- Lloyd, J. (2007). The Truth About Gen Y. Marketing Magazine 112 (19): 12-22.

- Marsh, H.W. & Hocevar, D., 1985. Application of confirmatory factor analysis to the study of self-concept: First- and higher-order factor models and their invariance across groups. Psychological Bulletin, 97, 562–582.

- Meyer J P, Stanley D J, Herscovitch L and Topolnytsky L (2002). Affective, Continuance and Normative Commitment to the Organization: A Meta-analysis of Antecedents, Correlates, and Consequences. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 61, 20-52.

- Meyer, J. P., & Allen, N. J. (1991). A three-component conceptualization of organizational commitment. Human Resource Management Review, 1, 61-89.

- Meyer, J. P., & Allen, N. J. (1991).A three-component conceptualization of organizational commitment. Human Resource Management Review, 1, 61-89.

- Meyer, J. P., Allen, N. J., & Smith, C. A. (1993). Commitment to organizations and occupations: Extension and test of a three-component conceptualization. Journal of Applied Psychology, 78(4), 538-551.

- Meyer, J.P. and Allen, N.J. (1997). Commitment in the Workplace: Theory, Research, and Application. Thousand Oaks, CA : Sage.

- Mohd Hanif, I. & Chia, A. (2013). The challenge of talent retention in today’s globalised economy. HR Asia, 17, 18-19.

- Mowday, R.T., Porter, L.W., and Steers, R.M., 1982. Employee-Organizational Linkage: The Psychology of Commitment, Absenteeism and Turnover. NY: Academic Press.

- Porter, L., Steers, R., Mowday, R. and Bouilan, P. (1974). Organizational commitment, job satisfaction and turnover among psychiatric technicians. Journal of Applied Psychology, 603‐609.

- Price, J. (2001). Reflections on the Determinants of Voluntary Turnover. International Journal of Manpower, 22 600-624.

- Reichers, A. (1985). A review and reconceptualization of organizational commitment, Academy of Management Review, 10( 3), 465–476.

- Robbins, S.P., Judge, T.A. and Vohra, N. (2011), Organizational Behavior , NJ: Pearson, Upper Saddle River

- Small and Medium Enterprise Corporation. (2013). 2012-2013 Annual Report of SME. Retrieved from http://www.smecorp.gov.my/vn2/node/71.

- Sousa-Poza, A. (2007). The Effect of Job Satisfaction on Labor Turnover by Gender: An Analysis for Switzerland. The Journal of Socio-Economic, 36, 895–913.

- Steers, R.M. (1977). Antecedents and outcomes of organizational commitment”, Administrative Science Quarterly, 22, 46‐56.

- W.L. Kuean, S. Kaur and E.S.K., 2010. The Relationship between Organizational Commitment and Intention to Quit: The Malaysian Companies Perspectives. Journal of Applied Sciences, 10: 2251-2260.

- Wiener, Y. & Vardi, Y. (1980). Relationship between job, organization, and career commitment and work outcomes-an integrity approach. Organizational Behavior and Human Performance, 26, 81-96.

- Zainudin, A., 2012. Structural Equation Modelling Using Amos Graphic. Shah Alam: Universiti Teknologi MARA Publication Centre (UPENA).

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

30 November 2016

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-016-7

Publisher

Future Academy

Volume

17

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-471

Subjects

Business, management, behavioural management, macroeconomics, behavioural science, behavioural sales, behavioural marketing

Cite this article as:

bin Salahudin, S. N., bin Alwi, M. N. R., bt Baharuddin, S. S., & Abd Samad, N. I. B. (2016). Generation Y : Organizational Commitment and Turnover Intention. In R. X. Thambusamy, M. Y. Minas, & Z. Bekirogullari (Eds.), Business & Economics - BE-ci 2016, vol 17. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 448-456). Future Academy. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2016.11.02.41