Abstract

The Malaysian female labour force participation increased from 47.2% in 2004 to 54.1% in 2015 but this is not alarming as the number of female students in tertiary institutions outweigh the male students. However, the issue is while the female labour force participation rate is highest in the 25-34 years age group (72%), it dropped 5 percentage points to 67% in the 35-44 years age group. A research by Talent Corp (2014) shows that the top three reasons women dropout from the workforce are: to raise a family, lack of work-life balance and to care for a family member. So, this perception study examined whether family friendly policies (FFP) could be a tool to retain women in the labour market and subsequently a tool to manage the nation’s resource. The main aims of this study are: firstly, to examine whether there is a relationship between demographic factors and women’s decision to remain in the labour market, and secondly, to examine whether FFP may encourage them to remain in the labour. Using a self-administered questionnaire, working women who were married were identified in the Klang Valley. A total of 158 usable questionnaires were collected in June 2016. Cross tabulation analysis and frequency analysis were used. The crucial findings showed that women who work in organisations with FFP have higher intentions to continue working compared to women who work in organisations without FFP. This study found that ethnicity, occupational sector and having children below 6 years old are significant factors that influence women’s decision to remain in the labour market. Family friendly policies can be a pertinent tool for resource management to retain married women in the labour market. Hence, the government and private sector should collaborate together in the enforcement of family friendly policies at the workplace.

Keywords: Flexible working arrangementsFamily friendly policies

Introduction

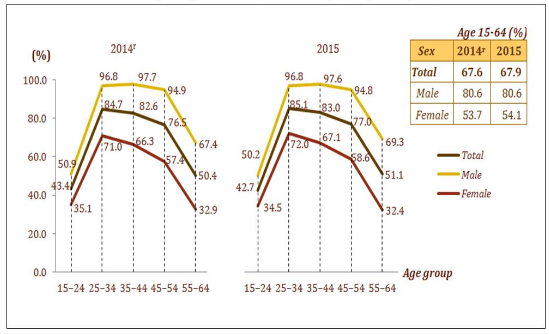

The Malaysian female labour force participation rate (LFPR) increased from 47.2% in 2004 to 54.1% in 2015 and this is not alarming as the number of female students in tertiary institutions outweigh the male students. The development of the female labour force in the Malaysian economy has seen a significant rise, seeing more girls pursuing tertiary education, which in turn closes the gender gap between male and female and hence, propagates gender equality in Malaysia. Figure

Based on the LFPR report in 2015 (Department of Statistics, 2016), it was recorded that the male LFPR had reached up to 80.6 per cent. The increase of females employed contributes to the increase of the overall LFPR. The report shows that female participation in the labour force has increased by 0.4% from 53.7% in 2014 to 54.1% in 2015 while male participation in the labour force has remained unchanged compared to previous years at 80.6%.

Even though the female labour force participation shows an increasing trend in Malaysia, it is still considered low compared to the male labour force participation in the neighbouring countries (World Bank Report 2015). It is important to increase women’s participation in the labour force because this can be instrumental in building economic growth. Increasing women’s participation in the workforce is the right thing to do as it is smart economics. Besides contributing to a higher productivity and income growth, it also helps in investing in the next generation and enhances the quality of decision making (World Bank, 2012). In the Asia-Pacific Human Development Report, the United Nations Development Program stated that if female LFPR is increased to 70%, it would boost Malaysia’s GDP by 2.9%. (World Bank, 2015).

The increase in women’s participation in the labour market is important in order to fully utilise all the resources that the country has. Ismail and Sulaiman (2014) indicate that participation of women in the labour market is vital and essential for economic development in a fast growing country. Therefore, the government needs to play a significant role in empowering women by initiating policies that will help them participate and remain in the workforce, as well as encourage them to re-enter the workforce. Their skill and talents are needed to boost the country’s economy. When all the resources are fully utilised without wasting any talent, it is easier for Malaysia to move to a high income nation by 2020.

The study by PricewaterhouseCoopers (PwC) Malaysia commissioned by Talent Corp Malaysia Berhad in their report on Diversity in the Workplace survey, 2013 showed that a majority of the corporations in Malaysia did not practice family friendly policies (FFP) or flexible work arrangements (FWA). This statement is supported by Subramaniam & Selvaratnam (2010) who found that only 16 per cent of companies in the Klang Valley truly adapted FFP. This in turn demotivates women who exit the labour force due to the challenges faced by them. Less conducive working environment due to lack of family friendly policies and inflexible working practices will keep women out from the job market (Daily News, 2015).

Family friendly policies are policies designed to minimise the impact of work on family life; this includes a variety of leave for maternity and paternity, sickness, emergencies and compassionate reasons, career breaks and extended leave, flexible time such as part time and registered days off (Hartin, 1994). Therefore, these policies enable the employees to balance the demands of paid work and personal life (Subramaniam & Selvaratnam, 2010). FFP are part of the policy initiatives that can be taken by the government to encourage more women to remain in the labour market. Increase in the female labour force will reduce gender inequality, reduce poverty and help in boosting the economic growth.

In the 10th Malaysian Plan, the women’s LFPR was targeted to achieve 55 per cent; however, the number was not achieved where female LFPR reached only 54.1 per cent.

Figure

A research conducted between the Association of Chartered Certified Accountants (ACCA) and Talent Corp in 2013 revealed that the three top reasons women leave the workforce are: to raise a family, lack of work-life balance and to care for a family member who is either their child or old parent. In other words, the survey results indicate that women quit from the workforce due to the inability to juggle between work and home as there is a lack of flexibility in their working environment. Therefore, this research attempts to capture the demographic factors that can influence women’s decision to remain in the labour market. This perception study also examined whether FFP may be a tool to retain women in the labour market and manage the nation’s resource. The main aims of this study are to identify the demographic factors which may have an influence on women’s interest to continue working and whether FFP may encourage them to remain in the labour market.

Literature review

2.1 Theory of Labour Supply

The labour force participation rate of women in the market involves the decision of women, particularly married working women, to remain or to leave the workforce. Becker’s income leisure model indicates that the intention to continue working depends on the market wage rate where it must exceed the reservation wage rate (Becker, 1970). Besides that, an individual will also tend to remain in the workforce due to other factors such as taste and preference for work, number of working hours and other non-labour income.

Work will become more attractive if the wage rate is higher, and thus it will encourage more women to participate in the labour force; whereas, for the working women, increase in wage rate will attract them to work more and they might be willing to give up their leisure time in order to work extended work hours (Kaufman & Hotchkiss, 2005).

The extended work leisure model which explained household perspective and allowed multiple use of time showed that time allocation is not for a single individual only, but also allocated between different family members where it can be divided into three activities. First is time that is spent in the labour market to earn some income; second is time spent for household production such as having dinner together with family; and, lastly time can be used in actual consumption of goods and services. Becker’s model thus explained that as wage increases, an individual is encouraged not only to substitute their time with non-market activities to market activities, but also activities that are comparatively time-intensive such as cooking a meal at home to income-intensive activities like dining outside. Thus, at certain levels of income, this substitution effect may reduce the mothers’ time at home and encourage more women to participate and remain in the labour force.

2.2 Demographic factors and women in the labour market

Based on a primary study, Ismail and Sulaiman (2014) found that age has a significant influence on married women’s labour supply. Their logistic regression model showed a negative relationship between age and women’s participation in the labour market. Basically, every additional one year of a married women’s age will reduce the probability of them working in the labour market. Ragoobur, Ummersingh and Budhoo (2011) found that the coefficient of the age variable is positively and highly significant towards women’s decision to remain in the labour market where age has an inverted U-shaped correlation with female labour force participation. It suggested that women will join the labour market when they complete their studies and will continue to work until the maximum level of participation is reached (Contreras et al., 2010).

By using LOGIT models to determine the female participation in labour force, Pastore and Tenaglia (2013) found that age is statistically significant with the female participation in the labour market. The results indicated the probability of female participation in the labour market increases with age; however, it had the U-shaped pattern. It showed the probability of females employed decreasing as they approach the retirement age.

In terms of children and women’s participation in the labour market, the number of children is the main factor that influences married women’s labour supply in Malaysia. Ismail and Sulaiman’s (2014) study on 4000 households in Peninsular Malaysia, found that the number of children has an inverse relationship with the married women’s decision to work where increase of one more child tends to reduce the probability of married women working in the labour market.

This scenario is also similar in Europe where there exists a negative significant relationship between Italian and foreign mothers with the number of children and participation at work in North-East Italy (Giraldo, Zuanna-Dalla and Rettore, 2015). The results showed that the higher the number of children, the larger the proportion of housewives, whereby a greater number of women leave the labour market. Italian and foreign mothers tend to take care of their own children despite sending them to public or private childcare service centres. This is consistent with the data from the Italian Survey of Births, which shows that 20% of mothers stopped working at least for a while after their babies were born and at least 14% of them decided to permanently leave their jobs.

Hartani, Abu Bakar and Haseeb (2015) found that there is a negative relationship between fertility rate and female labour force participation rate for the ASEAN-6 countries. The results from Fully Modify OLS (FMOLS) showed that a 1% increase in the female total fertility rate will reduce the female labour force participation rate by 0.44%. The highest negative effect was in Indonesia while the smallest negative effect was observed in Thailand.

Mishra and Smyth’s (2010) research in twenty eight OECD countries (Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development) found that there is a negative relationship between total fertility rate and the female labour participation rate in the workforce. The results also showed that there is bidirectional granger causality with a negative relationship between both variables as it indicates role of a woman as a mother and also as an employer. Contreras and Plaza (2010) also showed a negative relationship between the number of children and female participation in the labour market in Chile. The results showed that the presence of children below four years old in a family will reduce the probability of female participation in the labour market in that country.

The spouse’s monthly income also influences women’s decision to work. Research done in a district in Punjab by Hafeez and Ahmad (2002) found that an increase in spouse’s monthly income will decrease the probability of women’s participation in the labour force. It is said that women who live in more wealthy families are less likely to participate in the labour force.

Azid, Khan and Alamasi (2010) also found that spouse’s employment level and income has a significant influence on labour force participation of married women in Punjab. The regression results showed that there is an inverse relationship between spouse’s income and the labour force participation of married women. Lower level of income earned by spouse will lead to a higher labour supply from married women. However, a study done by Ismail & Sulaiman (2014) using logistic regression analysis found that husband’s wage and own wage does not significantly influence the married women’s labour supply in Malaysia.

Research Methodology

This paper seeks to identify the demographic factors that may influence the women’s decision to remain in the labour market. This study was conducted in the Klang Valley area, the central business region of Malaysia.

Non-probability sampling design of convenient and purposive sampling was used to identify the target population where the identified respondents must be married working women in the age group of 25-45 years old and must be working in the Klang Valley area. A total of 200 questionnaires were distributed; however, only 158 were usable.

The self-administered questionnaire has closed ended questions and was designed by using multiple choice questions and likert scale questions with the statement on a five-point scale from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree” (Sekaran and Bougie, 2013). The questions were adapted from Sullivan and Mainiero (2007), Talent Corp and ACCA report (2012), and LPPKN report (2016).

A pre-test was done to check questionnaire comprehension and to correct any ambiguity. The questionnaire was divided into four sections: Section A consisted of eleven items on the demographic profile of the respondents; Section B and C were related to family friendly policies on work-life balance and job satisfaction which consisted of five items and three items, respectively; Section D consisted of three items on women’s intention to work and their preferences on income generating activities once they left the labour market. The data was analysed by using SPSS software version 21 and cross tabulation analysis was used to analyse the findings in this study.

Analysis and Findings

The objective of this study is to identify the effect of demographic factors on women’s decision to remain in the labour market. Cross tabulation analysis was used to identify whether there is any correlation between demographic factors and women’s decision to remain in the labour market.

Based on the findings above, working women in the age group of 30 to 34 years old have high intention to continue working (60 %), followed by working women aged 35 to 39 years old (56.3%). These findings are consistent with the labour force report from the Department of Statistics (2015) showing a decreasing trend in the female LFPR where women with caring roles drop out from the labour market (Talent Corp, 2013). However, in this study, age does not have a significant influence on women’s intention to continue working. This was contradictory to the study done by Ahmed (2002) who found that age has an influence on women’s decision to remain in the labour market.

In terms of educational level, 58 per cent of the respondents who held a degree certificate intend to stop working. However, respondents with post graduate qualification intend to continue working compared to other educational levels (50%). However, educational level also did not have a significant relationship with women’s intention to remain in the labour market.

The findings also indicated that 60 per cent of the working women who were married and intended to stop working stayed in Kuala Lumpur compared to 54 per cent who stayed in Selangor. This might be due to the traffic congestion that they need to face every day as Kuala Lumpur is where most of the jobs are concentrated. However, the results show that location does not have a significant influence on women’s intention to remain in the labour market.

As for ethnicity, it was found that Indians had the highest intention to continue working at 67 per cent, followed by Chinese at 47 per cent and Malays at 41 per cent. It can be said that Malay working women were leaning more towards the traditional perception that staying at home is much better for them and Islam encourages men to go to work instead of women. This study found that ethnicity has a significant influence towards women’s decision to remain in the labour market.

Working women who were married and had 3 children and more had the lowest (44%) intention to remain in the labour market. This could be due to the time spent by women to take care of their children. This finding is consistent with the Talent Corp survey report 2013, which indicated that the tops reason for most women to leave the workforce was to raise a family.

The next demographic factor analysed was occupational sector of the respondents. Table

The employment level shows that respondents who were working in the middle management had less intention to continue working work with 42 per cent. A p-value of 0.782 indicates that employment level does not influence women’s decision to remain in the labour market.

Women with a monthly income of RM 4001 and above had the highest intention to continue working. 60 per cent of working women who earned a monthly income of RM 5001 to RM 6 000 intended to continue working, followed by 52 per cent in the income range of RM 4001 to RM 5000 and 50% in the income range of RM 6 001 and above. Even though the results show that higher income earned meant higher intention for women to continue work, they also show that monthly income does not influence women to remain in the labour market.

The effect of spouse’s monthly income on the intention of women to continue working is varied. Table

Table any children. This results conform to a study by Contreras and Plaza (2010) who found a negative significant relationship between number of children and female participation in Chile, which explains that the presence of children below four years in a family will discourage women to participate in the labour force.

Supported by the p-value of 0.018, children aged 6 years and below had a significant relationship with women’s decision to remain in the labour market. However, this study also found that there is no significant relationship between having children between 6 to 12 years and women’s intention to remain in the labour market.

However, Table

This section describes family friendly policies (FFP) offered in the respondent’s workplace.

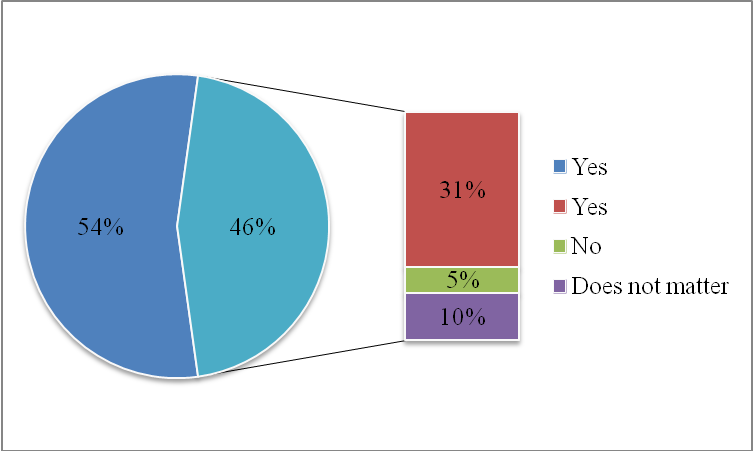

Figure

Among the 46 per cent of the respondents who claimed that there were no FFP in their organisations, 31 per cent preferred to work in an organisation with family friendly policies. 10 per cent of them were indifferent and only 5 per cent of the respondents did not prefer to work in organisations with family friendly policies.

Table

This study shows that in terms of demographic factors, ethnicity, occupational sector and having children below 6 years old have a statistically significant effect on women’s decision to continue working in the labour market. And moreover, working women working in organisations which offer FFP have intentions of continue working.

Conclusions and Recommendations

Based on the findings, the main conclusions which can be drawn are: firstly, ethnicity, occupational sector and number of children of respondents aged 6 years and below influence women’s decision to remain in the labour market; secondly, caring responsibility of young children have an influence on women’s decision to remain in the labour market; and thirdly, organisations with family friendly policies have a significant influence on women’s decision to remain in the labour market.

In order to retain women’s participation in the labour market, the government and private sector should collaborate in the enforcement of family friendly policies at the workplace. Firstly, organisations should treat FFP as a vital policy measure and implement them, especially with an increasing number of female students graduating and entering the labour market. This can be done on a case to case basis and not as a comprehensive policy for all employees. Many FFP such as flexible working time, working form the home and permanent part time create a positive and friendly workplace eco-system which allows better family management.

Secondly, the Malaysian government has been supportive of FFP since mid 2000s, but a more proactive role needs to be taken to monitor and regulate the implementation of these FFP in the private sector. The government should also provide more incentives to encourage more organisations to practice FFP at the workplace, especially flexible working arrangements, career break, nursing rooms and childcare centres. As children have a significant influence on women’s decision to remain in the labour market, the government and employers need to take action to provide work flexibility so that the women employees can concentrate and focus more on developing their career without neglecting their family responsibilities.

As this study only looked at a small sample in the Klang Valley, future studies should look at larger samples throughout the whole country to draw further conclusions.

As the country moves towards achieving Vision 2020, i.e. an industrialised nation status, it is vital that a change in mindset both at micro level and macro level is highly necessary for women’s decision to remain in the labour market. One immediate way will be by leveraging on the idea of FFP as a strategic approach to empower women to balance work and life as well as a pertinent tool for resouce management.

References

- Azid,T., Khan, R. E.A., and Alamasi, A.M.S. (2010). Labor force participation of married women in Punjab (Pakistan). International Journal of Social Economics. 37 (8)

- Contreras, D., and Plaza, G. (2010). Cultural Factors in Women’s Labor Force Participation in Chile. Feminist Economics.16 (2). 27-46

- Daily News (2015). Malaysia- Lack of Family Friendly Policies Keeping Women out of the Job Market. Retrieved from http://www2.staffingindustry.com/row/Editorial/Daily-News/Malaysia-Lack-of-family-friendly- policies-keeping-women-out-of-the-job-market-34247

- Dildar, Y. (2015). Patriarchal Norms, Religion and Female Labour Supply: Evidence from Turkey

- Eleventh Malaysia Plan (2016). Anchoring Growth on People (2016-2020)

- Giraldo, A., Zuanna-Dalla, G., Rettore, E., (2015).Childcare and participation at work in North East Italy: Why do Italian and Foreign mothers behave differently?. Journal of Statistical methods & application. 24 (2), 339-358

- Farre, L. & Vella, F. (2007). The intergenerational Transmission of Gender Role Attitudes and its implications for female labour force participation

- Hafeez, A., and Ahmad, E., (2002). Factors Determining The Labor Force Participation Decision of Educated Married Women in a District of Punjab. Pakistan Economic and Social Review. XL (1), 75-88.

- Ismail, R & Sulaiman, N (2014). Married Women Labour Supply Decision in Malaysia Asian Social Science 10 (3), 221-231

- Kufman, B.E. & Hotckiss,.J.L.(2006) The Economics of Labour Market. Thomson/South–Western, 7th edition

- Labor Force Survey Report, Malaysia, 2015. Department of Statistics Malaysia

- Malaysia Progress Report, Beijing Declaration & Platform for Action (2015)

- Malaysia (2010). Tenth Malaysia Plan Report (2010- 2015)

- Mirzaie, I. A. (n,d) Female’s Labor Force Participation and Job Opportunities in the Middle East. Department of Economics.

- Mishra. V., and Smyth,R., (2010). Female Labor Force Participation and Total Fertility Rates in the OECD: New Evidence from Panel Cointegration and Granger Causality Testing. Journal of Economics and Business. 62. 48-64

- National Population and Family Development Board (LPPKN) (2016). Fifth Malaysian Population and Family Survey Report.

- Pastore. F., Tenaglia. S. (2013). Ora et non Labora? A Test of the Impact of Religion on Female Labor Supply (IZA Discussion Paper No. 7356). Retrieved from http://ftp.iza.org/dp7356.pdf.

- Ragoobur-T.V., Ummersingh, S. & Bundhoo,Y., (2011). The Power to Choose: Women and Labor Market Decisions in Mauritius. Journal of Emerging Trends in Economics and Management Sciences (JETEMS) 2(3):193-205.

- Sekaran, U. & Bougie, R. (2013). Research Methods for Business: A Skill Building Approach: John Wiley & Sons Inc. Sixth Edition

- Subramaniam,G., Tan P L, Baah R, Ahmad Atory N.A. (2015). Do Flexible Working Arrangements Impact Women’s Participation In The Labour Market? A Multiple Regression Analysis. Malaysian Journal Of Consumer And Family Economics 18 (-), 130-140

- Subramaniam, G. Ali,E., Overton,J., (2010) Are Malaysian Women Interested In Flexible Working Arrangements At Workplace? Business Studies Journal (SI), 83-95

- Subramaniam, G. & Selvaratnam, D.P. (2010). Family friendly policies in Malaysia: Where are we? Journal of International Business Research 9 (1), 43

- Sullivan, S. E. & Mainiero, L.A. (2007). Kaleidoscope Careers: The Kaleidoscope Career Company Audit. Retrieved from http://www.sciendirect.com.

- Talent Corp & ACCA Report (2013). Retaining Women in the Workforce

- Talent Corp & PwC Report (2013). Diversity in the Workplace

- Hartani, N.H., Bakar, N.A.A, & Haseeb, M. (2015). The Nexus between Female Labour Force Participation and Female Total Fertility Rate in Selected ASEAN countries: Panel Cointegration Approach. Modern Applied Science. 9 (8)

- World Bank Report (2012). Malaysian Economic Monitor, Unlocking Women’s Potential.

- World Bank Report (2015). United Nations Development Programme.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

30 November 2016

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-016-7

Publisher

Future Academy

Volume

17

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-471

Subjects

Business, management, behavioural management, macroeconomics, behavioural science, behavioural sales, behavioural marketing

Cite this article as:

Subramaniam, G., Kamarozaman, N. N. H., & Leong, T. P. (2016). Family Friendly Policies - A Tool for Resource Management among Working Women. In R. X. Thambusamy, M. Y. Minas, & Z. Bekirogullari (Eds.), Business & Economics - BE-ci 2016, vol 17. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 274-286). Future Academy. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2016.11.02.26