Abstract

Restaurants providing halal (permissible according to Islamic jurisprudence) food are important to Muslims. However, many factors influence customers’ intention to patronise halal restaurants. This study examines the antecedents of patronage of halal restaurants. The study questions whether there is an effect of perceived value, perceived usefulness and culture on the intention to patronise halal restaurants and whether religiosity moderates the relationship among these variables. The purpose of this study is to explore the factors that influence Muslim customers’ intention to patronise halal restaurants. The study specifically investigates the relationships among perceived value, perceived usefulness, culture, religiosity and intention to patronise halal restaurants. The study is based on a sample of 323 halal restaurant consumers. The questionnaire measures the following variables: perceived value, perceived usefulness, vertical collectivism, horizontal collectivism, vertical individualism, horizontal individualism, religiosity and intention to patronise halal restaurants. The study shows that both perceived value and perceived usefulness have a direct influence on behavioural intention to patronise halal restaurants. In regards to the effect of collectivism and individualism, only horizontal collectivism and vertical individualism have a direct influence on purchase intention. The current study also finds that religiosity moderates the relationship among perceived value, perceived usefulness, horizontal collectivism and horizontal individualism with respect to behavioural intention. The study shows that the Muslim intention to patronise halal restaurants is influenced by the perceived value, perceived usefulness of halal restaurants and culture which is also moderated by the Muslim level of religiosity.

Keywords: Halal restaurantCultureReligiosity

Introduction

All of us are concerned about the food we eat as food helps our bodies function properly and may serve to maintain health and prevent or treat disease. In addition to its important role in human survival, food is also considered an important dimension of interaction among different ethnic, social and religious groups (Riaz & Chaudry, 2004). Islam is the second largest religion in the world with around 1.59 billion adherents, equal to 23.2% of the world’s total population in 2010 ("The future of world religions: Population growth projections, 2010-2050," 2015). The religion specifies the types of foods which are permissible to eat by Muslims. These permissible foods under Islamic jurisprudence are called halal (Wilson & Liu, 2010).

According to the Pew Research Center ("The future of world religions: Population growth projections, 2010-2050," 2015), Islam is the fastest-growing religion; it is expected to expand at a rate of 35% until 2050. The Muslims growth rate is faster than the growth rate of the global population. By 2050, the number of Muslims is expected to reach 2.8 billion (30% of the world’s population) while the projected number of Christians in 2050 is expected to reach 2.9 billion (31% of the world’s population) ("The future of world religions: Population growth projections, 2010-2050," 2015). This fast-growing Muslim population will directly stimulate the growth of halal consumer goods and services ("Promising outlook for halal industry In Western Europe," 2016). According to the State of the Global Islamic Economy Report 2015/2016, the global halal food and lifestyle sector is predicted to grow by 6% by 2020 ("Global halal food sector expected to grow 5.8% by 2020," 2015).

As the largest Muslim country in the world with a population of about 218.68 million, or 10.51% of the entire world's population in 2014, Indonesia has experienced significant growth in the restaurant market ("World Muslim population", 2016). In 2013, the Indonesian hotel and restaurant industry contributed around 14.33% of gross domestic product (GDP). One driver of this growth is the emerging population of middle class and affluent consumers in the country. As the number of Muslims in Indonesia reached 88% of its total population in 2014 ("World Muslim population", 2016), the demand for halal products and services, including restaurants, also rose in the country.

Problem Statement

Despite halal being the common denominator in consumption for Muslims, it is worth noting that countries and cultures may reflect differences in approach whilst adhering to the same frameworks (Wilson & Liu, 2012). According to Sandikci (2011), even though halal is the common denominator for all Muslims, their interpretation, negotiation and experience with the halal framework in daily life are vibrant and complex. Furthermore, since marketing efforts have become gradually more globalised, understanding cross-cultural consumer psychology is now a goal of mainstream consumer research (Shavitt, Torelli, & Riemer, 2010). Thus, it is important for researchers to examine the interaction and intersection of religion with other variables or ideologies such as ethics, values, culture and subjectivities in consumption and marketing research (Sandikci, 2011).

Purpose of the Study

The current study will examine the influence of perception, culture and religiosity on halal restaurant patronage intention, using Indonesia as the context of the study. Specifically the study will investigate the influence of perceived value, perceived usefulness, collectivism and individualism value on halal restaurant patronage intention.

Research Question

The study questions whether there is an effect of perceived value, perceived usefulness and culture on the intention to patronise halal restaurants. Furthermore, the study also questions whether religiosity moderates the relationship among these variables.

Literature Review and Hypotheses Development

5.1 Perception and behavioral intention

5.1.1 Perceived value of restaurants with halal certification

Perceived value is defined as an overall assessment of the usefulness of a product based on the perception of the benefits to be received by consumers and the benefits to be provided by the product (Zeithaml, 1988). Holbrook (1999) describes perceived value as the value individuals derive from a comparison of the value of one product against other products, so perceived value is subjective and experiential. In line with Zeithaml (1988) and Holbrook (1999), other researchers (Sanchez-Fernandez & Iniesta-Bonillo, 2007) state that from the consumer side, perceived value can be viewed from two perspectives: the economic perspective and the psychological perspective. The economic perspective associates perceived value with a price that consumers are willing to pay and the usefulness of the goods to consumers. In contrast, the psychological perspective associates values with cognitive and affective aspects that influence consumer decision-making in the purchase (Gallarza, Gil-Saura, & Holbrook, 2011).

Perceived value and perceived usefulness reflect cognitive beliefs associated with intention to purchase and use of products labeled as halal. According to Ajzen and Fishbein (1980), intention is determined by two basic factors: personal factors and social factors. Personal factors include the individual evaluation of something that is reflected in attitudes and behaviour (Ajzen & Fishbein, 1980). The social factor refers to the individual's perception of something that is based on the pressure the individual receives to perform or not perform a behaviour (Ajzen & Fishbein, 1980). Previous research also reports that consumers' evaluation of the value and usefulness of the product triggers an emotional response that triggers intention (Chang & Dibb, 2012).

To determine the value of a product, the consumer evaluates the product attributes that will provide basic information to consumers. In the context of food products, product labels provide a range of benefits for consumers by contributing to the perception related to the value and usefulness of the product. For example, consumers assign high hedonic value to products with an organic label (Sirieix & Tagbata, 2008) because consumers assume that the product has a better taste than non-organic products (McEachern & McClean, 2002), is better for the human body and is more environmentally friendly and morally justifiable (Jamal & Sharifuddin, 2015). In regards to the halal label on the packaging of snacks, the label provides value-expressive benefits for consumers by building a perceived value that is as positive for the consumer as it is for Muslim society. Food carrying a halal label is considered compliant with religious requirements, safe and not harmful to the body.

Based on the above arguments, the following research hypothesis is formulated:

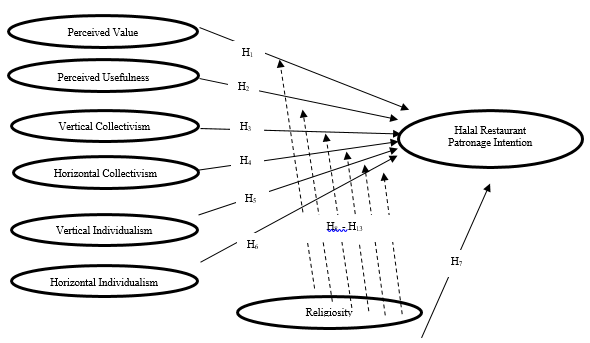

H1: Perceived value has a positive and significant influence on halal restaurant patronage intention.

5.1.2 Perceived usefulness of halal certification

Perceived usefulness is the degree to which a person believes that using a particular system will have implications for the improvement of job performance (Davis, 1989). Following Davis (1989), this study defines perceived usefulness as consumers’ belief that buying products labeled as halal will enhance their experience in shopping for products (Jamal & Sharifuddin, 2015).

Perceived usefulness has been shown to directly influence the intention to use a system (Guritno & Siringoringo, 2013) and previous research has shown a positive relationship between perceived usefulness and intention to use the system (Benbasat & Wang, 2005; Davis, 1989). Research has also revealed that perceived usefulness leads to individual intentions (Amoako-Gyampah, 2007). One study revealed that perceived usefulness plays an important role in shaping consumer purchasing intentions (Ozok, Wu, Garrido, Pronovost, & Gurses, 2014). Cue utilisation theory and some literature on signaling provide a conceptual framework for understanding perceived value and perceived usefulness of the halal label. Based on cue utilisation theory, consumers use symbols or gestures (cues) to help them make decisions (Dodds, 1995).

Related to halal food products, including halal restaurants, Jamal and Sharifuddin (2015) reveal that product labels provide a variety of benefits for consumers that contribute to perceived usefulness. Muslim consumers in the United Kingdom consider the halal label as a gesture to provide relevant information to enhance the perceived value and perceived usefulness of the label itself. The halal label in restaurants makes it easier for customers to make faster consumption decisions and thus the perceived usefulness of halal food labels positively affects purchase intentions. Therefore:

H2: Perceived usefulness has a positive and significant influence on halal restaurant patronage intention.

5.2 Culture and behavioural intention

5.2.1 Vertical and horizontal collectivism

Collectivism and individualism as cultural elements influence consumer consumption processes (Xie, Bagozzi, & Ostli, 2013). Collectivism refers to a society which has tight integration where members of the society are expected to look after the interests of their in-group and to have no opinions and beliefs other than the opinions and beliefs of their in-group (Hofstede, 1983). Cooperation is stressed in a collectivist society (Ahuvia, 2002). Both collectivism and individualism can be divided into what is called vertical collectivism, horizontal collectivism, vertical individualism and horizontal individualism. Vertical collectivism refers to a view of the self as a part of a collective group where inequalities among members are accepted and horizontal collectivism is defined as the perception of the self as a part of the collective group, with an emphasis on equality (Singelis, Triandis, Bhawuk, & Gelfand, 1995).

The Muslim community basically adheres to a collective culture, meaning that the Muslim community has always considered important recommendations from the people in the community (Jamal, 2003). Collective culture itself is divided into two aspects related to the vertical collective adherence to hierarchy and authority (Shavitt, Lalwani, Zhang, & Torelli, 2006) and the collective which places more emphasis on the horizontal, social equality and cooperation with one another. Shavitt et al. (2006) argue that the halal label can be seen as a cultural symbol for Muslims so that the vertical collectivist individual intent to purchase a product with a halal label reflects their conformity to their reference group or leader. Therefore:

H3: Vertical collectivism has a positive and significant influence on halal restaurant patronage intention.

Horizontal collectivism is a culture that emphasises equality (Triandis & Gelfand, 1998) and focusses on relationships of interdependence between equals (Shavitt et al., 2010). Thus, a group of Muslims who are horizontal collectivists and live in a non-Islamic country will feel cynical about a halal label on food; they may think that a multi-national company or non-Islamic company is trying to manipulate the information so as to increase sales or, in a non-purchase situation, they may think that the non-Muslim group is resorting to negative stereotyping (Chylinski & Chu, 2010). Therefore:

H4: Horizontal collectivism has a negative and significant influence on halal restaurant patronage intention.

5.2.2 Vertical and horizontal individualism

Individualism refers to a culture that is more concerned with individual interests than the interests of the family or group (Bellah, Madsen, Sullivan, Swidler, & Tipton, 1985). Individualism also refers to a society with loose ties between individuals where individuals are expected to look after their own self-interest and the interests of their immediate family (Hofstede, 1983). Vertical individualism refers to an autonomous individual and acceptance of inequality while horizontal individualism refers to an autonomous individual and stresses equality (Singelis et al., 1995).

Lam (2007) finds evidence that consumers who are individualist versus collectivist can dampen the effect of the group members, social norms and media marketing because they tend to uphold the choice themselves without being disturbed by external influences. Sharma (2010) proves this theory in the automobile industry.

Bonne and Vermeir (2007) state that Muslims who are individualists consider consumption to be everything that is closely related to beliefs and personal choices of the individual. Muslim community members who have assimilated the local individualist culture also feel less motivated to comply with peer pressure and normative rules of the Muslim group (Jamal & Sharifuddin, 2015). Based on the above arguments, researchers develop the following hypotheses:

H5. Vertical individualism has a negative and significant influence on halal restaurant patronage intention.

H6. Horizontal individualism has a negative and significant influence on halal restaurant patronage intention.

5.3 Religiosity and behavioural intention

Religion influences human attitudes and behaviour in many ways (Delener, 1994), including in food choice and food purchase decisions, in a variety of community groups (Dindyal & Dindyal, 2003; Musaiger, 1993). The influence of religion in food consumption decisions also depends on the extent to which a person adheres to the teachings of his or her religion, or religiosity level (Pepper, Jackson, & Uzzell, 2009). A similar effect of religiosity on purchase intention is also found in Muslim groups as Muslims are forbidden from eating certain foods (Sack, 2001). However, Jamal and Sharifuddin (2015) find that the effect of perceived value and perceived usefulness on purchase intention depends on the level of religiosity.

Based on the above discussion relating to halal restaurants, the hypotheses of this study related to religiosity are as follows:

H7. Religiosity has a positive and significant influence on halal restaurant patronage intention.

H8. Religiosity positively moderates the relationship between perceived value and halal restaurant patronage intention.

H9. Religiosity positively moderates the relationship between perceived usefulness and halal restaurant patronage intention.

There is still an ongoing debate on the relationship regarding the effect of religiosity on culture, especially in relation to individualism or collectivism values (Sampson, 2000). In the context of Islam, Wilson and Liu (2010) argue that what is considered legitimate or illegitimate can vary based on Muslims’ cultural differences. Shavitt et al. (2006) report that some consumers in collectivist cultures form collectivism vertical compliance and increase cohesion and the status of their group. Research conducted by Wilson and Liu (2010) related to communities of British Muslims finds that Muslims in Britain are always trying to identify products that are halal and products that are not haram (not permissable) because they are aware that consuming products that are haram will bring the risk of spiritual punishment for the sin at a later date. In connection with the above statement, the following hypothesis can be formulated:

H10. Religiosity positively moderates the relationship between vertical collectivism and halal restaurant patronage intention.

The horizontal collectivist culture emphasises equality (Triandis & Gelfand, 1998). People who are in this culture highly value honesty and cooperation between people (Triandis & Gelfand, 1998). Because of the honesty and openness, even though in non-Muslim countries, Muslims have a certain cynicism towards halal certification, but people’s level of religiosity can offset the negative feelings that arise (Jamal & Sharifuddin, 2015). Based on the above discussion, the following hypothesis can be formulated:

H11. Religiosity negatively moderates the relationship between horizontal collectivism and halal restaurant patronage intention.

Individualism and religiosity do not have to be contradictory (Triandis & Gelfand, 1998). It is possible for someone who is individualistic to practice his or her religion in everyday life. The principles of Islam also teach that every Muslim is related to the independent choice to practice his or her religion. Based on the above discussion, the following hypotheses are offered:

H12. Religiosity negatively moderates the relationship between vertical individualism and halal restaurant patronage intention.

H13. Religiosity negatively moderates the relationship between horizontal individualism and halal restaurant patronage intention.

Based on all the above arguments, the research framework shown in Figure

Research Method

The data were collected using a non-probability sampling technique via an online survey of 323 Muslim respondents. Sample characteristics of the respondents were as follows: Ages of respondents ranged from 18 to 55 years and the majority of the respondents were female (n=213). Confirmatory factor analysis by LISREL program was employed and two absolute goodness-of-fit indices were applied to measure the fit of the estimated models: Normed chi-squared (χ2/df) and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA). Satisfactory model fits are indicated by a normed chi-squared (χ2/df) between 2.0 and 5.0 and RMSEA values less than or equal to 0.07 (Hooper, Coughlan, & Mullen, 2008; Hu & Bentler, 1999).

Analysis

Based on table

The first hypothesis testing shows the significant impact of perceived value on intention of customers to patronise halal restaurants. Verbeke et al. (2013) suggest that the halal label on a product is an incremental innovation of food producers to hook the Muslim market. The current findings concur with those of Jamal and Sharifuddin (2015) as halal-certified restaurants provide value-expressive benefits for consumers by building a perceived value that is as positive for the consumer as it is for Muslim society so that these consumers tend to return and recommend the restaurant to others.

The result of the second hypothesis testing indicates that the presence of a label or certification of halal food products and restaurants is useful to facilitate Muslim consumers in shopping (Jamal & Sharifuddin, 2015). Additionally, for the Indonesian Muslim community, halal certification is a safeguard for consumers to avoid eating unclean food. Based on the above statement, one can conclude that the halal label increases confidence, adoption rates and consumption of products, especially restaurant products.

The rejection of the third hypothesis and the acceptance of the fourth hypothesis imply a shift in Indonesian values. Indonesia is known as a country which is collectivist with high power distance. However, it is the horizontal collectivism rather than vertical collectivism that significantly influences Indonesians’ intention to patronise halal restaurants. Horizontal collectivism refers to a culture of togetherness that emphasises equality (Trandis & Gelfand, 1998). The results might be influenced by the structural change in the culture of Indonesia, which is influenced by improvement of the Indonesian economic condition. This economic improvement indirectly drives not only Muslim consumers but also Indonesian society in general to be equal in power although previously they were collectivist in nature. According to Hofstede (1980, 1991), an increase in national wealth usually drives the society to be low in power distance.

The result of the fifth hypotheses testing reflects the development of the individualism value in Indonesia. Vertical individualism refers to the culture of individualism associated with the hierarchy whereby adherents of the culture of individualism are more concerned with individual interests than the interests of the family or group (Bellah et al., 1985). In the context of restaurants, individuals who have both vertical and individualist characteristics may dine in halal restaurants to signal their status and to distinguish themselves from other individuals.

The sixth hypothesis testing shows no significant effect of horizontal individualism on purchase intention. The study implies that Muslim consumers feel less motivated to comply with peer pressure and normative rules of the Muslim group.

The seventh hypothesis testing shows no significant and direct effect of religiosity on purchase intention. The insignificant influence of religiosity on intention may result from aspects other than religiosity that shape consumer behaviour to dine in halal restaurants. Intentional consumer behaviour to dine at halal restaurants is likely more influenced by the evaluation attributes (Ryu, Lee, & Gon Kim, 2012; Tsaur, Luoh, & Syue, 2015).

The eighth and ninth hypotheses testing shows significant positive moderation of religiosity on perceived value and perceived usefulness. The higher the level of the consumer’s religiosity, the more careful the consumer will be in choosing products to be consumed. In obedience to religious rules, the consumer will refrain as much as possible from consumption of products that do not follow halal, such as by not eating food from restaurants that are not certified halal. As noted earlier, the most important aspect of consumer perceived value is the aspect of safety in consuming food served by restaurants. Certified halal restaurants give consumers a sense of security through the guarantee provided by the certification. Therefore, the halal certification at a restaurant can increase the perceived value of the restaurant in the eyes of society, especially among Muslims who have a high level of religiosity.

The tenth hypothesis on the moderating effect of religiosity on the relationship between vertical collectivism and purchase intention is not supported. The study indicates that aspects of religiosity do not affect a person's willingness to follow the advice of a person who occupies a higher position in the society with respect to consumption of food in a halal-certified restaurant.

The eleventh hypothesis testing shows that religiosity moderates negatively the relationship between horizontal collectivism and purchase intention. The results imply that the higher the religiosity of Muslims, the lower the relationship between horizontal individualism and halal restaurant patronage intention. This might apply to negative information. Indonesia tends to be a talkative society in disseminating information, especially information that is not good. Also, Indonesian society is prone to disseminate information without checking the truth of such information. The more religious a person, the greater the desire to protect fellow Muslims. This causes the information related to the issue of halal food to quickly spread without being checked first and to result in lower intention to patronise halal restaurants.

The twelfth hypothesis investigates the role of religiosity in the effect of vertical individualism on purchase intention with respect to halal restaurants. In connection with the decision to dine at a restaurant certified as halal, the choice of restaurant will make some people feel they are in a better position than others. Dining in a halal restaurant is considered to convey religious prestige and can be used as a differentiator between individuals by other individuals because halal certification in the restaurant is a symbol of a high level of religiosity (Triandis & Singelis, 1998). However, in this study, aspects of religiosity were not significant in strengthening the influence of vertical individualism against behavioural intention. This may occur because people of a religious community do not compare themselves with others on compliance problems. A religious society that always tries to obey the rules and practices of pure religion as a form of obedience without being seen as individualistic is considered better than others.

The last hypothesis testing examines the moderating role of religiosity in the relationship between horizontal individualism and intention to patronise a halal restaurant. The analysis shows that a Muslim who is a horizontal individualist will more easily be assimilated with the surrounding environment than an individual who is a collectivist (Jamal & Sharifuddin, 2015). A horizontal individualist will find that following peer pressure or normative regulations coming from the community is not too important. They assume that each individual action is an individual choice freely made.

Aspects of religiosity’s debilitating effect on behavioural intention and horizontal individualism may be elevated because in Indonesia, the culture is collectivist (Voronov & Singer, 2002). The Indonesian Muslim community as a representation of the collective community considers that obedience to the subjective norm is important as a marker that Muslims are a part of these communities. Therefore, the motivation for a religious person observing the subjective norm can also be viewed from two angles: People comply with the subjective norm because the subjective norm is also the norm of their religion or they abide by the subjective norm because they feel uncomfortable with the social sanctions that arise when they do not abide by it.

Conclusion

Perceived value and perceived usefulness directly influence Muslim consumers’ intention to patronise halal restaurants. This indicates that halal certification in the restaurant results in a more favourable opinion of the restaurant among consumers. In addition, halal certification is also seen as useful to the consumer in determining consumer behaviour. However, religiosity has no direct influence on customers’ intention to patronise halal restaurants. Religiosity serves as a moderating variable among perceived value, perceived usefulness, horizontal collectivism and horizontal individualism.

Acknowledgement

This work has been funded by the PITTA Grant to the Directorate of Research and Community Services at the Universitas Indonesia.

References

- Ahuvia, A. C. (2002). Individualism/collectivism and cultures of happiness: A theoretical conjecture on the relationship between consumption, culture and subjective well-being at the national level. Journal of Happiness Studies, 3(1), 23-36.

- Ajzen, I., & Fishbein, M. (1980). Understanding attitudes and predicting social behaviour.

- Amoako-Gyampah, K. (2007). Perceived usefulness, user involvement and behavioral intention: an empirical study of ERP implementation. Computers in Human Behavior, 23(3), 1232-1248.

- Bellah, R. N., Madsen, R., Sullivan, W. M., Swidler, A., & Tipton, S. M. (1985). Habits of the heart: Individualism and commitment in American life: JSTOR.

- Benbasat, I., & Wang, W. (2005). Trust in and adoption of online recommendation agents. Journal of the association for information systems, 6(3), 4.

- Chang, C., & Dibb, S. (2012). Reviewing and conceptualising customer-perceived value. The Marketing Review, 12(3), 253-274.

- Davis, F. D. (1989). Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS quarterly, 319-340.

- Delener, N. (1994). Religious contrasts in consumer decision behaviour patterns: their dimensions and marketing implications. European Journal of Marketing, 28(5), 36-53.

- Dindyal, S., & Dindyal, S. (2003). How personal factors, including culture and ethnicity, affect the choices and selection of food we make. Internet Journal of Third World Medicine, 1(2), 27-33.

- Dodds, W. B. (1995). Market cues affect on consumers' product evaluations. Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice, 3(2), 50-63.

- The future of world religions: Population growth projections, 2010-2050. (2015). Retrieved July 13, 2016, from http://www.pewforum.org/2015/04/02/religious-projections-2010-2050/

- Gallarza, M. G., Gil-Saura, I., & Holbrook, M. B. (2011). The value of value: further excursions on the meaning and role of customer value. Journal of consumer behaviour, 10(4), 179-191.

- Global halal food sector expected to grow 5.8% by 2020. (2015). Retrieved July 13, 2016, from http://www.gulfood.com/Content/Global-halal-food-sector-expected-to-grow-58-by-2020

- Guritno, S., & Siringoringo, H. (2013). Perceived usefulness, ease of use, and attitude towards online shopping usefulness towards online airlines ticket purchase. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 81, 212-216.

- Hofstede, G. (1983). The cultural relativity of organizational practices and theories. Journal of international business studies, 14(2), 75-89.

- Holbrook, M. B. (1999). Consumer value: a framework for analysis and research: Psychology Press.

- Hooper, D., Coughlan, J., & Mullen, M. (2008). Structural equation modelling: Guidelines for determining model fit. Articles, 2.

- Hu, L.-t., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural equation modeling: a multidisciplinary journal, 6(1), 1-55.

- Jamal, A. (2003). Marketing in a multicultural world: The interplay of marketing, ethnicity and consumption. European Journal of Marketing, 37(11/12), 1599-1620.

- Jamal, A., & Sharifuddin, J. (2015). Perceived value and perceived usefulness of halal labeling: The role of religion and culture. Journal of Business Research, 68(5), 933-941.

- McEachern, M. G., & McClean, P. (2002). Organic purchasing motivations and attitudes: are they ethical? International Journal of Consumer Studies, 26(2), 85-92.

- Musaiger, A. O. (1993). Socio-cultural and economic factors affecting food consumption patterns in the Arab countries. The Journal of the Royal Society for the Promotion of Health, 113(2), 68-74.

- Ozok, A. A., Wu, H., Garrido, M., Pronovost, P. J., & Gurses, A. P. (2014). Usability and perceived usefulness of personal health records for preventive health care: A case study focusing on patients' and primary care providers' perspectives. Applied ergonomics, 45(3), 613-628.

- Pepper, M., Jackson, T., & Uzzell, D. (2009). An examination of the values that motivate socially conscious and frugal consumer behaviours. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 33(2), 126-136.

- Promising outlook for halal industry In Western Europe. (2016). Retrieved July 13, 2016, from http://www.bmiresearch.com/news-and-views/promising-outlook-for-halal-industry-in-western-europe

- Riaz, M. N., & Chaudry, M. M. (2004). The value of Halal food production-Mian N. Riaz and Muhammad M. Chaudry define what Halal and kosher foods are, describe why they are not the same thing, and what is required of processors and. Inform-International News on Fats Oils and Related Materials, 15(11), 698-701.

- Ryu, K., Lee, H.-R., & Gon Kim, W. (2012). The influence of the quality of the physical environment, food, and service on restaurant image, customer perceived value, customer satisfaction, and behavioral intentions. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 24(2), 200-223.

- Sampson, E. E. (2000). Reinterpreting individualism and collectivism: Their religious roots and monologic versus dialogic person–other relationship. American Psychologist, 55(12), 1425.

- Sanchez-Fernandez, R., & Iniesta-Bonillo, M. Ã. (2007). The concept of perceived value: a systematic review of the research. Marketing theory, 7(4), 427-451.

- Sandikci, O. (2011). Researching Islamic marketing: past and future perspectives. Journal of Islamic Marketing, 2(3), 246-258.

- Shavitt, S., Lalwani, A. K., Zhang, J., & Torelli, C. J. (2006). The horizontal/vertical distinction in cross-cultural consumer research. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 16(4), 325-342.

- Shavitt, S., Torelli, C. J., & Riemer, H. (2010). Horizontal and Vertical Individualism and Collectivism. Advances in culture and psychologyVol, 1, 309-350.

- Singelis, T. M., Triandis, H. C., Bhawuk, D. P. S., & Gelfand, M. J. (1995). Horizontal and vertical dimensions of individualism and collectivism: A theoretical and measurement refinement. Cross-cultural research, 29(3), 240-275.

- Sirieix, L., & Tagbata, D. (2008). Consumers willingness to pay for fair trade and organic products.

- Triandis, H. C., & Gelfand, M. J. (1998). Converging measurement of horizontal and vertical individualism and collectivism. Journal of personality and social psychology, 74(1), 118.

- Triandis, H. C., & Singelis, T. M. (1998). Training to recognize individual differences in collectivism and individualism within culture. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 22(1), 35-47.

- Tsaur, S.-H., Luoh, H.-F., & Syue, S.-S. (2015). Positive emotions and behavioral intentions of customers in full-service restaurants: Does aesthetic labor matter? International Journal of Hospitality Management, 51, 115-126.

- Voronov, M., & Singer, J. A. (2002). The myth of individualism-collectivism: A critical review. The Journal of Social Psychology, 142(4), 461-480.

- Wasserbauer, M. (2015). Restaurant market experiencing great growth, opportunity in Indonesia. Retrieved July 14, 2016, from http://www.cekindo.com/restaurant-market-experiencing-great-growth-opportunity-in-indonesia.html

- Wilson, J. A. J., & Liu, J. (2010). Shaping the halal into a brand? Journal of Islamic Marketing, 1(2), 107-123.

- Wilson, J. A. J., & Liu, J. (2012). Surrogate brands–the pull to adopt an ‘other’nation, via sports merchandise. International Journal of Sport Management and Marketing, 11(3-4), 172-192.

- World Muslim population (2016). Retrieved July 14, 2016, from http://www.muslimpopulation.com/World/

- Xie, C., Bagozzi, R. P., & Ostli, J. (2013). Cognitive, emotional, and sociocultural processes in consumption. Psychology & Marketing, 30(1), 12-25.

- Zeithaml, V. A. (1988). Consumer perceptions of price, quality, and value: a means-end model and synthesis of evidence. The Journal of marketing, 2-22.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

30 November 2016

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-016-7

Publisher

Future Academy

Volume

17

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-471

Subjects

Business, management, behavioural management, macroeconomics, behavioural science, behavioural sales, behavioural marketing

Cite this article as:

Fara, A., Hati, S. R. H., & Daryanti, S. (2016). Understanding Halal Restaurant Patronage Intention: The Role of Perception, Culture and Religiosity. In R. X. Thambusamy, M. Y. Minas, & Z. Bekirogullari (Eds.), Business & Economics - BE-ci 2016, vol 17. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 176-188). Future Academy. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2016.11.02.17