Abstract

To combine good teaching, educational reform and continuously improve the efficiency of the education system requires a workforce able to meet society’s expectations. Teacher-training institutions still deliberate on the optimal way to select and recruit candidates appropriate for teaching and the criteria for their evaluation. Research on teacher-training has attempted to identify the personal characteristics that teaching candidates should exhibit, and teacher-training focuses on several factors: the background of the applicants; their motives for choosing teaching; their attitude to education and their expectations from training. The fact that many graduates of teachertraining institutions drop out of the profession raises questions concerning the training costs of preparing teachers for school, the quality of the training which may cause teachers to quit their work, the profession’s status in society and the manner of induction into the profession, which may by comparison, have less orderly induction procedures than other professions. Relevant aspects from this research for the purpose of the present research are: who are those who turn to education. This paper includes a history of teacher-training in Israel relating especially to the rapid changes in education in the 21st century and the era of IOT (Internet of Things). Out of a desire to improve the evaluation process of student teachers we constructed and modified the process for the assessment of student teachers’ practicum experience. Integration of new assessment tools and a new curriculum can improve teachertraining to create a worthy teaching candidate equipped appropriately with 21st century teaching skills.

Keywords: Training teachersNew skillsIOT in EducationEvaluation

Introduction

We live in a technological era characterised by swift changes. This condition presents new

challenges in different areas of life particularly in education. The field of education is one of the

important fields in which society is continually required to adapt itself to change, in order to prepare

the younger generation to cope with the demands of the next century. For this purpose teachers need to

be “trained today to educate tomorrow the citizens of the day after tomorrow” (The Council, 1987: 28).

The world of education tends to be characterised by periods of reform. One notable reform in the field

of education in the United States took place in the 60s during the tension between the Soviet Union and

the United States, following the launch of the Russian Sputnik. Educators perceived a need to restore

the previous status of learning material as a central element in education. Theory was developed

concerning the knowledge structure of the different disciplines and educators focussed more on the

development of the intellect. “The pendulum of education” swung then from progressive education

methods (Dunne & Harvard, 1993) back to more conservative methods.

There is no doubt that education reforms in the United-States have had an effect on the Israeli

education system, despite the differences between them (Mor, 1996). Government reports published in

the 1980s led to the current reform: the first report “A Nation in Risk”, shocked the USA. The report

exposed the failures of American education compared with education in other countries. Then the

reports of two committees: Holmes Group and the Carnegie Forum report, 1986indicated the need for

reform to maintain the USA’s economic status in the world stressing the need for excellence in order to

successfully compete with other states (Shuluv-Barkan, 1991). The reports showed that school

graduates entering the world of employment were bereft of the basic skills required for work. The

economic institutes need employees with a thinking capability for irregular tasks. It seemed that over

half the graduates of high schools had a low reading level, while modern technology needed higher

level thinking skills, which could only be acquired through broader and deeper education, able to

produce people with independent thinking capabilities.

The need to improve the quality of the education system arises, among other things, when teaching

becoming a recognized profession (Bullough, 1989) and the status of teachers becomes equal with that

of other professions. Accelerated change processes in modern society present the education system

with the need to nurture higher thinking skills and independent learning capabilities in its students. All

this requires good teachers, with a broad education in the fields of teaching and pedagogy, while to

attract people with a high intellectual level and social involvement, the status of the teaching profession

must also be improved. The end of the 20th century was a critical moment for an essential change in

preparing teachers for the new millennium (Darling-Hammond, 1994). Therefore the reform implied by

both above-mentioned reports deals mainly with teacher-training. This reform therefore involves

raising the education level of the teacher to a master’s degree, establishing professional bodies that give

teaching permits, deciding on the standards for joining the profession, differentiation in the teaching

staff (differences in knowledge, commitment, education and licensing), and creating a connection

between higher-education institutions and the schools (Shuluv-Barkan, 1991).

Reform in the United States suggested changes in the training of teachers that would mostly be

based on systematic knowledge of teaching in practice, increasing practicum experience at school

during training, in schools prepared for this purpose, which would serve as training centers (Darling-

Hammond, 1994) and the cancellation of the first degree in education. Anyone who intends to be a

teacher would learn for a master’s degree in teaching. During the academic year, most teacher-training

students would be gaining practical experience at school and theoretical studies would be learned

during the summer vacation.

The present article begins with a history of teacher training in Israel. As noted above the Israeli

teacher-training institutes have followed similar directions to those adopted in the USA in order to raise

the level and quality of training. These directions include a change in the accreditation and certification

processes, extending the length of the training, changes in the contents of training programs and in

graduation criteria.

Problems of teacher-training

One of the major problems in teacher-training is to ensure a smooth transition from training into the

reality of school life. The hardships of novice teachers during the first years of their teaching work,

difficulties and a high dropout rate particularly at the beginning of school work are well documented

(Elbaz, 1993). In addition new teachers need to cope with different aspects of the profession: its status,

professional burnout, since education is a job for life, and on the other hand society’s criticism

concerning the teacher’s level and his or her quality as well as criticism of the school’s achievements

(Goodlad, 1993). Research has stimulated reforms and changes in order to improve the field of teacher-

training (Goodlad, 1993). However progress and changes in this field are still relatively limited (Lanier

& Little, 1986).

Some of the identified problems are that: The boundaries of the training programs and their

objectives are not defined yet as in other professional occupations and there is a separation between

disciplines and pedagogy (Goodlad, 1991). There is no connection between theory and practice,

between the training and the teacher’s work at school (Kagan, 1992). Teacher-educators who mentor

the student in school may be seen as having little prestige(both in colleges and in universities),

therefore they avoid supporting a recovery plan for teacher-training and improvement of the teacher’s

status (John, 1993). There may be a disconnection between training and performance in the school

reality. Some call it “a collision between two worlds” (Feiman-Nemser, 1996). The teachers who

graduate from training institutions are quoted as speaking of a gap between what they learned and what

was required from them at school. The source of the disconnection is in the preference for theoretical

learning in training, prioritizing the theory over the practicum (Zeichner & Gore, 1990). Other

problems may be being prepared for teaching in class but not for working with colleagues in school and

the community (Kuzmic, 1994), use of high abstract terms they don’t really understand (both the

teachers’ educators and the students), difficulties in translating the theory into the concrete practical

level, meaning the implementation of the theories, when working in class. The teacher may be in a state

of cognitive dissonance when he or she discovers the gap between what is required when exposed to

class life and what has been learnt in training.

Findings show that in training teacher-educators simplify the situation at school and avoid dealing

with the social and pedagogic variables effecting the teacher’s decisions (Borko, 1989). Even if the

novice teacher accepts the simplified principles, he or she cannot implement them because they do not

know how to overcome this gap (Bashi, 1992). The pedagogic content is perceived as theoretical talk

and not as a means of defining practical goals.

This gap between training and work was enlarged in Israel because of increasing academization,

since more and more academic courses were added to the teacher-training curriculum, which were not

always relevant to the teacher’s needs and as a result the time devoted to pedagogic guidance and

practical work decreases. There is no integration between the theoretical field and the pedagogic

professions (e.g. psychology is learned as a theoretical subject without adapting the theoretical terms to

the practical experience in class). There is a call for such adaptation but it does not exist in reality.

Helping trainee teachers to apply the theory is in fact left to the mentors and novice teachers and this

may be an impossible task for them (Mor, 1996).

(Goodlad, 1994). In Israel there is a document called “The Guiding Model” for teacher-training in

Israel. It was written by the permanent committee for academic courses in education workers training

institutions of the Council for Higher Education. And although it declares that “the college itself, as an

institution, should try and find different ways for training teachers and monitor their success”, and

(Mor, 1996): “an institute may include, in its program, any teachings which reflect its special nature”, it

appears that it is difficult to escape the dictated structure and to include and test new training contents

in a college’s training program. The model stipulates many more study hours than a graduate diploma

requires in higher-education institutions; therefore teacher-training institutions do not deviate from the

norm and are not able to present any serious changes to the existing model. Pedagogic and teaching

areas are confined because of stated requirements.

In light of the experience gathered in the academization stage, Aizen (1994) calls for a

reexamination of the curriculum dictated by “the guiding model” and argues that the model should be

adjusted to the needs of society in Israel. The reasons for the disconnection between training and

employment in the school:

of experience as a pupil in school. One of the critiques concerning the effectiveness of teacher-training

is that it does not affect the manner in which the graduate teaches in class. Training has failed to enable

what is learned during the training to be transferred to the reality of teaching in class. As noted above,

the novice teacher’s past experiences also have a strong influence on their teaching including their own

personal developmental processes, their opinions and beliefs and the previous educational experience

they accumulated both as students and as workers in various educational systems – more than the

influence of patterns and knowledge they have acquired during the training period (Goodlad, 1992).

an optimistic, promising approach. The graduate finishes training equipped with an ideological load he

or she wishes to pass on to their students. However, in practice the teacher senses gaps between what is

desirable and what exists, and slowly the graduate’s optimistic spirit is eroded and gives way to

surrender, routine and disinterest. Training may seem too utopian (Goodlad, 1992).

http://dx.doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2016.09.110 There is a lack of correspondence between the teaching patterns experienced during training and

the knowledge the trainee acquires regarding teaching methods and techniquesthat are actually used

asked to do with the students (Kremer-Hayon & Ben-Peretz, 1986).

The novice teacher comes to school from the student culture in the training college into a different

change required, the discontinuity between training and entering the profession – all these elements

force the student to spend time adjusting to the school patterns and not to use what he was taught over

the past several years. During the transition from college to school, an outside professional is needed to

help the teacher apply what he has learned in theory to practice.

Possible ways of preventing such disconnection

Training can integrate theoretical concepts with practical work, or develop the ability to identify and

interpret practical examples in class and discuss the level of their compatibility with educational

theories (Bashi, 1989). A training course can demonstrate teaching methods and lesson planning, and

alter the relative proportions of theoretical studies and practical work in favor of practical education

and work, where theory is combined with practical experience (Lanier & Little, 1986); such a course

can ensure continuity between training and the beginning of work in school, meaning the continuation

of pedagogic instruction during the first year of work. This would create a more natural continuity of

socialization from training to teaching (Goodlad, 1992).

Additional problems of teacher-training include:

The content “pendulum” creates periodic changes in emphases in the curriculum: from an emphasis

on general studies to an emphasis on pedagogic-theoretical studies and practical work, and so on and

this means that fundamental elements may be given less emphasis in the training course. The novice

teacher, a graduate of the teacher-training program, is likely to lack important teaching skills such as:

the ability to analyze a class – diagnosing the level of the class and the level and difficulties of each

student, ability to set goals according to the results of the analysis and preparing learning material for a

heterogeneous class with different levels of learners in it (John, 1993).

There are loose connections between training, academy, and schoolteachers involved in training.

Without proper coordination: pedagogic mentor, school, and training teacher may give incompatible

and even contradicting messages instead of uniform, synchronized messages to the trainee teacher.

There are no clear measurable criteria for the success of the trainee. Evaluation is often likely to be

guided, by the intuition and ideology of the mentor-instructor providing inappropriate guidance to

training students, during their practicum experience. A strong and primal connection between the

“field” and the training institute can improve selection and filtering processes through the stipulation of

clear measurable criteria for success, and those who are inappropriate will drop out or be removed in

early stages.

Increased dropout at the end of training and during the first years of teaching

45 percent of teacher-training graduates are integrated into teaching in Israel in the first year

after graduation. In the USA, 60 percent of the training institutes’ graduates enter teaching (Darling-

Hammond, 1994), dropout greatly increases the cost of training each teacher.

Discontinuity between training and teaching in school

Teacher-training courses in Israel do not include an internship year (recently, in 1996, the Ministry

of Education started to introduce internship, as an experiment, in several teacher-training institutions).

Today, a teacher learning for an academic degree in teaching in college studies only theoretical courses

during the fourth year of study. Many students do not bother coming to a training school during this

year, and those who do teach, receive no pedagogic guidance from the college instructor (the mentoring

project, which is the topic of this research, includes among its participants fourth year students, but

they are a minority). In light of the difficulties involved in induction into the teaching profession, the

teacher feels that there is a gap between what is learned in the college training course and reality in the

school (Peleg, 1992).

The professional career of teachers:

The development of a teacher’s career is a subject that has been subject to increasing research in the

past twenty years. Thus a large amount of knowledge has been accumulated on the subjects of teaching

and the work of teachers. Additionally, the technological society and all its characteristics:

competitiveness, ambitiousness, and quick changes, teachers face high requirements for teaching quality

and demands they are held accountable for the scholastic and educational achievements of the students.

The next section presents several approaches to the analysis of the teacher’s career throughout their

years of work, from training to retirement: (1). According to cognitive development theories. (2) A

taxonomy of teachers’ concerns according to Fuller et al. (3) Theories regarding the development of

stages in life (age and tenure) (4) Combining a development of professional thinking with stages in life.

The professional development of teachers is a continuous process throughout their professional life, a

continuity of growth and development, of change and striving for perfection. Even Dewey (Dewey, 1938)

saw education as a process of changing states, forms, knowledge, attitudes and behaviour. This

development is one of the main goals of education; progress starts from an early, simple stage and moves

on to a later more complex and improved stage, and this is an irreversible process (Burden, 1990).

What is the next step in teacher-training?

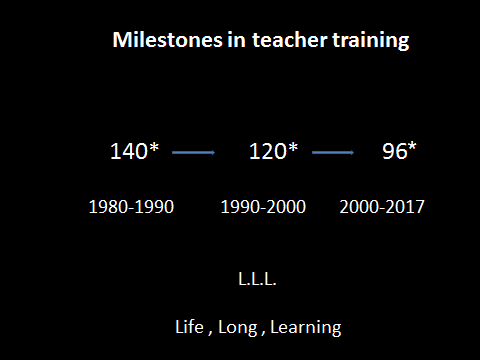

* Number of annual hours for the B. Ed. degree program in teaching

Until the 1980s it was common practice for teachers to be trained in a two-three year training

program in teacher-training seminars (the fore-runners of today’s teacher-training colleges) in order to

respond to increased demand for new teachers. In the 1980s, an academic program for teacher-training

was developed that included 140 annual academic hours and this program was put into practice during

the 1990s in a reduced program of 120 annual hours. From the end of the 1990s, teacher-training

programs in Israel included 96 annual hours of study. The trend to reduce the number of requisite hours

stemmed from an assumption that a teacher should continue with Life-Long Learning and improved

professionalization, also known as the Three L’s approach.

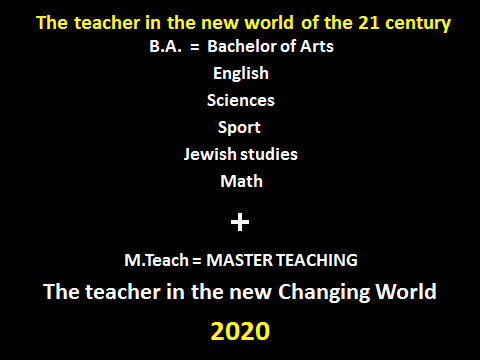

Today Israeli teacher-training colleges have entered a new era necessitating an approach that will

position the teaching discipline as a respected profession. The teacher of the future who wishes to train

for work in 2020 will need to study for a Bachelor’s degree in a specific discipline (e.g. mathematics,

biology, English, Jewish studies, sport etc.). Only after completing this first degree, if the candidate

wishes to become a teacher and is found suitable to do so, then they will be required to study for an

M.Teach.

Summary

This article attempted to describe the contemporary spirit of teacher-training against a

historical overview of teacher-training in the past. It appears that the trend over the last forty years has

demanded greater professionalism from the teaching profession and transformed the teaching vocation

into a profession like any other for example: doctors, lawyers etc. Continuous processes of professional

transformation (Raichman & Simon, 2013) have altered the teaching profession’s role from the

transmission and delivery of knowledge to a profession in which the future teacher is expected to be a

leader, innovator and instructor have accelerated. It is hoped that this development will enable the

teaching profession to provide a professional response to the demands of the modern era with values and skills appropriate for the demands of the 21st century.

References

- Aizen, D. (1994). Reality and Vision as Dynamic Factors in the Development Processes of Teacher-Training in Israel, Dapim, 18, pp. 7-21.

- Bashi, Y. (1989). Teacher Training – Proposal for Experiment submitted to the Higher Education Counsel. Bashi, Y. (1992). Training teachers - A Proposal for an Experiment in Teacher Training presented to the Board of Higher Education.

- Borko, H. (1989). Research on learning to teach: Implication for graduate teacher preparation. In Woolfolk, A.

- (Ed.). Research Perspectives on the Graduate Preparation of Teachers, pp.69-87. Englewood Cliffs) N.J.: Prentice Hall.

- Bullough, Jr. V. (1989). First Year Teacher-A Case study Teacher College. New York and London: Columbia University.

- Burden, P.R. (1990). Teacher development. In Houston, W.R., Haberrnan1 M., & Sikula, J., (Eds.), Handbook of Research on Teacher Education. MacMillan Pub. Cornpany, pp. 311-328.

- Darling-Hammond, L. (1994). The Current Status of Teaching and Teacher Development in the U.S.A. Eric Document Reproduction Service, No. ED 379 229.

- Dewey, J. (1938). Experience and education. Free Press.

- Dunne, R., & Harvard, G. (1993). A Model of Teaching and Its Implications for Mentoring. In McIntyre, D. & Hagger, H. & Wilkin, M., (Eds). Mentoring: Perspectives on School-Based Teacher Education, pp. 117-129. London: Kogan.

- Elbaz, F. (1993). Teacher Thinking. A Study of Practical Knowledge. London & Canberra: Croom Helm. Feiman-Nemser, S. (1996). Teacher mentoring: A critical review. Eric Document Reproduction Service, ED No. 397 060.

- Goodlad, J. (1991). Why we need a complete redesign of teacher education. Educational Leadership, 49(3), 4-10. Goodlad, J. (1992) On Taking School Reform Seriously. Phi Delta Kappan, 74, (3), 232-238.

- Goodlad, J. (1993) School-University Partnership and Partner Schools. Educational Policy, 7 (1), pp. 24-39. Goodlad, J. (1994). Educational Renewal: Better teachers, better schools. Eric Document Reproduction Service No. ED 366 101.

- John, P.D. (1993). Practitioner or Academic? The Impact of institutional Culture on the Teacher Educator's Mindset.

- Kagan, D.M. (1992). Professional Growth among Preservice and Beginning Teachers. Review of Educational Research, 62(2), 129-169.

- Kremer-Hayon, L., & Ben-Peretz, M. (1986). Becoming a Teacher: The Transition from Teachers’ College to Classroom Life. International Review of Education, 32(4), 413-422.

- Kuzmic, J. (1994). A Beginning Teacher’s Search for Mentoring. Teacher Socialization, Organization, Literacy and Empowerment. Teaching and Teacher Education, 10 (1), 15-27.

- Lanier, J., & Little, J. (1986). Research on teacher education. In M. C. Wittrock (Ed.), Handbook of research on teaching (3rd ed., pp. 527-569). New York: Macmillan.

- Mor, D. (1996). Concerning Teacher Training in Israel. Dapim, 31, 23-25.

- Peleg, S. (1992). Mentoring in Teacher Assimilation During the First Year of Teaching – Research Findings – A Follow-up in Oranim, the Academic Division. Dapim, 14, 88-97.

- Raichman. B., & Simon. E. (2013). Between Pedagogy and Technology: A Two College Case Study - Training Israel’s Teachers to Meet the Challenges of the 21st Century is published in IJDIWC. The Fourth International Conference on e-Learning (ICEL2013).

- Shuluv-Barkan, S. (1991). Teaching and Careers – A Review and Discussion of the Professional Literature. Jerusalem: Henrietta Szold Institute.

- The Council (1987). The Teacher Federation; Teacher Training for the Third Millennium. Hed Ha’chinuch, 52(A), 28-34.

- Zeichner, K.M. & Gore, J.M. (1990). Teacher Socialization In Houston, W.R. & Haberman, M. & Sikula, J., (Eds), Handbook of Research on Teacher Education. MacMillan Pub. Company, pp. 329-348.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

04 October 2016

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-014-3

Publisher

Future Academy

Volume

15

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-1115

Subjects

Communication, communication studies, social interaction, moral purpose of education, social purpose of education

Cite this article as:

Simon, E. (2016). Training New Teachers in a Changing World. In A. Sandu, T. Ciulei, & A. Frunza (Eds.), Logos Universality Mentality Education Novelty, vol 15. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 883-890). Future Academy. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2016.09.110