Abstract

In what error correction during the speaking activities in a foreign language is concerned the opinions are divergent. While some specialists claim that the best way is to discuss them separately with the students, others argue saying that all the errors should be corrected on the spot. In this paper we will try to approach this issue by presenting the most important opinions on the matter in contrast with the actual situation – what it really happens in the classroom. After the administration of a set of questionnaires to both teachers and students of Romanian as foreign language we try to discover how errors in spoken language during the teaching and assessing activities are corrected. Finally, we will establish which are the most common, and liked methods of error correction, but also which of those are giving best results in the teaching process.

Keywords: Romanian as a foreign languageerror correctionspeakingteachingassessment

Introduction

In what error correction in a foreign language is concerned there are known and used various

methods. The goal of the present study is to illustrate the most used and appreciated methods of error

correction during the speaking activities in Romanian as a foreign language (RFL). During several

discussion had with our colleagues, teachers of Romanian and other foreign languages we came to

realize that each teacher had his own way of correcting the mistakes during the speaking activities, and

even more every method was quite different from the other one. Interesting was also the fact that each

person had strong arguments in favour of the method used, and none of the methods could be

considered as wrong by the others, if explained. Given the described situation, through our study we

wanted to answer a simple but important question, in our opinion:

administering questionnaires to the both groups involved in this matter – the teachers and the students.

Participants

In order to get a first result, we decided to focus only on our university, taking into consideration the

fact that the first doubts appeared exactly there. We sent questionnaires to 12 teachers, with the age

between 29 and 70, and to 50 students, with the age ranging from 16 to 32. The teachers were selected

taking into consideration the age (we wanted that each age stage to be represented) and the

involvement in the teaching activity. It should be kept in mind that our department has only 7 members

and several collaborators, so the total number isn’t very high compared to the 12 members selected

here. So, this is another reason why the number of the participants is so low. Regarding the students

involved, we only used our groups, from this academic year, but also from the previous one, students

that already are studying in different faculties and who are able to see their goal more clearly. We’ve

had a very heterogeneous group, with different mother tongue languages (L1). We are talking about:

Arabic, Albanian, French, Spanish, Russian, and Ukrainian. And quite homogeneous foreign languages

known (L2), also: English, Hebrew, Russian, Italian and Greek. Mainly, the regional languages in their

countries, and English, added to everyone. So, it is safe to say that all of them had already had an

experience with learning a foreign language, so they could state an opinion on the best method it suits

them in error correction.

Methodology Outline

We’ve started our research by looking to the specialists’ opinions on this topic and continued by

administering questionnaires to both students and teachers of RFL in our university. Following this

path we wanted to compare the general recommendations regarding error correction in a foreign

language with the actual situation. The main objective was to find out if the methods usually used by

the teachers are following the specialists’ recommendations and furthermore if these methods are

matching with what the students want and feel comfortable with during the classes. The questionnaires

used in this study were realized by the authors of the article, containing 2 parts, for the teachers, and 3

parts, for the students. The questions will be presented when discussing the results, while the entire

questionnaires can be seen upon request. Taking into account the limited space for the paper, we’ve

decided not to include them in the article, but to present the most important aspects where it’s

necessary.

The general recommendations

It is said that “few things are more discouraging to the production of a foreign language than to be

interrupted and corrected (or even to know that someone is hovering beside you ready to interrupt and

correct).” (Brown & Yule, 1984, p. 37) Opposite to what the children usually react (or don’t, because

they don’t value so much others’ opinions), the adults might pay more attention to this fact. (Burlacu,

Platon & Sonea, 2011, p. 42) Agreeing with this statement the obvious question appears:

do with the mistakes during the spoken productions? Do we let the student talk, without paying

attention to his mistakes or, do we interrupt him and help him, correcting the errors? Of course that our

first instinct, as teachers and native speakers is to correct what is unnatural to our ear. That is why we

tried to find some other specialized opinions on this matter. It seems that all depends on the type of the

activity – centred on pronunciation, on grammar, or it’s a real-life speaking activity. Harmer claims

that in the case of a situation centred on pronunciation, the teacher should interrupt and correct: “When

students are repeating sentences, trying to get their pronunciation exactly right, then the teacher will

often correct (appropriately) every time there’s a problem” (Harmer, 2007, p. 131). The same

observation is valid from Scrivener’s point of view in what concerns the grammatical structures, too

(Scrivener, 2005, p. 160-161). On the other hand, Linse and Bailey (Linse, 2005, pp. 60-61; Bailey,

2005) argue on the fact that not all the errors should be corrected, even though they are pronunciation

or grammatical mistakes: “I decide which errors I will focus on. I think about the children’s

development and any errors they may make because of interference from their native language” (Linse,

2005, p. 61). In the help of this last statement comes Brown and Yule’s statement “After years of

rigorous attention to pronunciation during the fifties and early sixties many teachers now accept that

the aim of achieving native-like pronunciation is not only unattainable but unreasonable. Nowadays the

teacher probably tries to achieve the set of phonological contrasts, but does not worry too much about

the phonetic detail” (Brown & Yule, 1984, p. 26). We tend to agree with the last statement, even more

knowing that there are students with great difficulties in using and mastering Romanian specific sounds

that are inexistent in their native languages. For example, if we have an Arabic native speaker learning

Romanian he will most certainly have difficulties in recognizing and uttering the differences between

the following phonemes:

will have a problem in pronouncing

pronunciation by adding an

when the teachers insisted on discriminating between the pair sounds, using the well-known technique

of minimal pairs. “Later writers have criticized this approach as being artificial and lacking in

relevance to language learners' needs.” (Brown, 1990, pp. 144-146) This is argued by Gillian Brown in

her book

the specific phonemes in text, but the most, in words, which was an artificial and inefficient way of

using the sounds. She had showed that if a student not so well prepared wouldn’t be able to recognize

and to repeat exactly the words/phrases he was asked to repeat, only demonstrates that the method

wasn’t necessary useful. (Brown, 1990, pp. 144-146) So, even practicing and correcting many times,

for sure even at advance level, C1 or C2 (***, 2001, pp. 21-42), the speakers will have specific errors

based on their mother-tongue language. Even Lado affirms that “learners are likely not to hear

differences between phonemes if the difference is not a phonemic one” (Lado, 1961, p. 15).

More convergent are the ideas when referring to real-life speaking activities. In those situations all

the authors we’ve seen agree on the fact that the fluency shouldn’t be affected by the accuracy (Linse,

2005, p. 61; Harmer, 2007; Brown & Yule, 1984; Scrivener, 2005, pp. 161-161). What is different in

all these last views is the way the errors are recommended to be corrected. While Linse suggests

reformulation (Linse, 2005, p. 61), Jeremy Harmer offers several different possibilities: reformulation,

discussion with the class or separately with the student and even the immediate correction, if this was

decided with the students before (Harmer, 2007).

The questionnaires administered to teachers

The teachers’ questionnaire had two parts, one referring to teaching and one, to assessment. In the first

part there was a question with 6 options (from

practices that were presented in the studies we’ve seen. The question was:

activities during the class, how do you correct the mistakes that occur (grammar, vocabulary,

pronunciation, word order or other type of mistakes): a. I interrupt and correct immediately; b. I ask the

other students to say the right form; c. I write the mistake on the blackboard, I explain and correct it; d. I

reformulate immediately the mistaken phrase; e. I note down the mistakes and I discuss them with all the

students at the end of the activity; f. I write down the mistakes and I discuss them with the student that

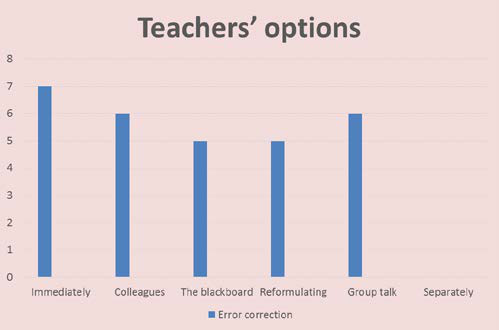

The first remark we should make is that the teachers chose up to four different ways of correcting

spoken productions, some even in contradiction (for example,

We can easily affirm that the teachers use more than one ways of correction. The preferred methods are

presented in

easiest technique for correction, the immediate correction, which was also one of the least

recommended ones by the specialists. On the other hand it’s the feedback offered separately, which

wasn’t chosen by anybody, because it wasn’t considered as a valid technique. The teachers commented

on this option as it follows: “usually there isn’t enough time to use this method. Anyway, a group

discussion seems to be more useful for everyone” or “If there are students that do not accept to be

corrected with their colleagues present, then we can use it, but we don’t trust is a profitable technique

for anyone.”

The teachers that chose the first option in spite of the recommendations motivated their choice

saying that “experience shows them that there are different types of students that need to be corrected

on the spot, otherwise they do not realize they’ve made a mistake.” We agree with the stated idea, there

are for sure students that prefer these option, but you might tend to use this method for everyone,

situation that will make uncomfortable some of the other students. Besides these teachers, there are

others that didn’t wanted to use this method, but “after discussing with their students they started to use

it”, due to the fact that this was the right way for those students. We’ve observed a third category, those

believing that simple mistakes need short interventions: “being a simple mistake, which doesn’t need

explanations, which might be a slip, can be immediately corrected” or “Being communicative

activities, I do not believe the errors are so serious, that is why I don’t give a lot of time to correct

them, so I correct them on the spot.” So, the contradiction comes between the statements that the errors

aren’t so important while the focus is on communication, and the fact that the teacher still interrupts the

communication in favour of accuracy, thing that undoes the initial idea. We’ve been able to see in all

the answers the tendency to give more importance to the accuracy (especially phonetic and

grammatical accuracy) in the expense of the fluency. The teachers tend to interrupt the speech in order

to correct a word said incorrectly or a grammatical structure used inappropriately instead of leaving the

act of communication taking place. If we want a real-life situation we consider that the right choice is

to let the partners do their parts, for sure the interlocutor will ask the speaker to repeat what he didn’t

understand or even more, he will correct his partner in speech by reformulating the idea stated before

or just resaying it correctly. So, everything might be solved in the end without our intervention. If not,

there will always be the other methods we can use.

From the graph we can see that option

teachers declared to use it. They justified their options saying that they use it “only when the focus of

the activity is the accuracy itself.” or “in the case of a mistake that shouldn’t be happening at one

specific level”. Those that chose the option

on the backboard and I try to obtain the right answer from the student that made the mistake, then from

the colleagues” or, they say they use it if more students make the same error. On the other hand, if the

mistake is not so serious, the teachers say they use reformulation, especially in questions or when it is a

word order error. The last type of correction, the discussion at the end, with the group, based on the

errors written down during the activity, the teachers say they use it when “there is time” or when “the

same mistakes repeat frequently and explanations are needed”, especially during discussions, debates

or arguments. There are teachers that consider this method to be time consuming and also difficult for

the teacher. It is true it needs a lot of energy and attention from teacher’s part, but we believe it can be

very useful for all the group. Maybe the teacher can choose to focus on a certain type of errors after the

activity.

Besides the 6 methods known in the specialized literature and included in the questionnaire, the

teachers questioned proposed 2 other ways, some with equivalent in the literature, some not. So, one

teacher said that she established a code with the students so that she is able to correct some mistakes

(pronunciation, grammar, vocabulary) on the spot. When she takes the hand to the ear the student

knows that there is an error that he tries to correct, and if he isn’t able to, his intervention isn’t stopped.

We believe that this technique could be useful in the case of simple errors like a word used or said

inadequately, or in the situation of a grammatical structure used incorrectly, because it doesn’t put the

student in an uncomfortable situation, but it can’t be used if the message is not well-transmitted or the

order of the words in phrase is inadequate. Maybe, it could be useful to set three signs, one for each

problem, to give more clues to the student talking and making the self-correction more probable.

Another method used by one of the RFL teachers is tongue twisters, in order to fix the pronunciation

errors, but also for learning new grammatical structures, exercises recommended also by Linse, to

develop fluency. Furthermore, the author suggests real-life examples of tongue twisters, made by the

students after some examples (Linse, 2005, p. 60).

In what the evaluation is concerned we could notice that the teachers share a common opinion: “we

do not interrupt and correct during assessment”. However, two out of the twelve subjects use to note

down the errors during assessment and discuss them with the students, without naming the ones that

did the mistakes. Not forgetting that the purpose of our activity is teaching the students a foreign

language, we don’t think that discussing the errors after the exams is a wrong choice, but helpful for

the students, even though many errors might have been made due to the pressure of the exam. So,

maybe in the case that the teacher from the group is also examining/evaluating his own students he will

be able to keep in mind only the important mistakes or situations in which the message wasn’t

transmitted, and omitting to discuss the errors that the student wouldn’t make in a stress-free situation.

The questionnaires administered to students

A very similar questionnaire was given to the students, too. The first question intended to verify if

the answers given by the teachers matched with the ones given by the students. So, they were asked to

say how the teachers correct the mistakes made during speaking activities. The same options the

teachers had were given to them, too, and the answers are presented below. We should keep in mind

that some of the students chose two options, confirming the idea stated in subsection

teachers use more than one method for correction. Out of the 50 students 35 said that the teacher

corrects the mistakes immediately, while 15 of them claimed that the teacher interrupts, but asks for the

right form from the students. The rest of 20 students said that the correcting of the mistakes takes place

after finishing the sentence/intervention, by writing the answer on the blackboard. None of the students

said that the teacher discusses at the end of the activity with the group or separately the errors occurred

during that activity. If we go back to the answers given by the teachers it is easy to notice that there are

some inconsistencies between the two groups at the answers unregistered by the students. Even though

the first three options coincide, that is correction occurring immediately, with the help of the colleagues

and by writing the right form on the blackboard, none of the students chose the options referring to the

teacher reformulating the sentence or the one referring to the group discussion at the end of the class.

We could notice that 5, respectively, 6 teachers claimed to use that method of error correction. So, we

could conclude saying that this inconsistency might be happening due to the fact that the students do

not realize the error correction which could show that the method isn’t in fact working, if they do not

see that they are corrected, they won’t change the way they use the language.

With the second question given to the students we’ve tried to find out how they are feeling while

different types of error correction happen. So, the question was:

interrupts you and corrects what you were saying?, b. the teacher writes the error you made on the

blackboard and explains it for all your colleagues?, c. the teacher explains why is something wrong

without saying who did the mistake?, d. the teacher explains separately what you said wrong?

At the first option

interrupted, even more they think that “in this way they will talk better” against what the studies say on

the immediate error correction (

our students are exclusively adults, really motivated to learn and to use the language as efficiently as

possible. And even working with the adults, there were 6 students confessing that they do not feel

comfortable if they are corrected and their colleagues can see that. This situation might result from the

fact that the adults are also very competitive, so they do not want the others see them

second option

way they find out it’s not a problem. There were also a number of 10 students that said

presented before. They are competitive, they don’t feel comfortable knowing that others see them

doing something wrong. Four of the students didn’t write anything at this question. At the third option

confidence, while 4 think is necessary for the teacher to say who did the mistake, because they might

not know it is about them. Again, four students didn’t give an answer. In what concerns the last option

motivated and they understand quicker if they are alone. Only 7 of them believe it’s not a good way of

error correction, because they trust that other students make the same mistakes and the explanations

can be useful for the others, too. Again, five students didn’t answer. It is a bit strange this last answer

taking into account the fact that the students stated that there isn’t happening that the error correction to

be given separately, fact confirmed by the teachers’ answers. This inconsistency can result from the

fact that the students might have said what they think they would feel in this case, not what really

happens.

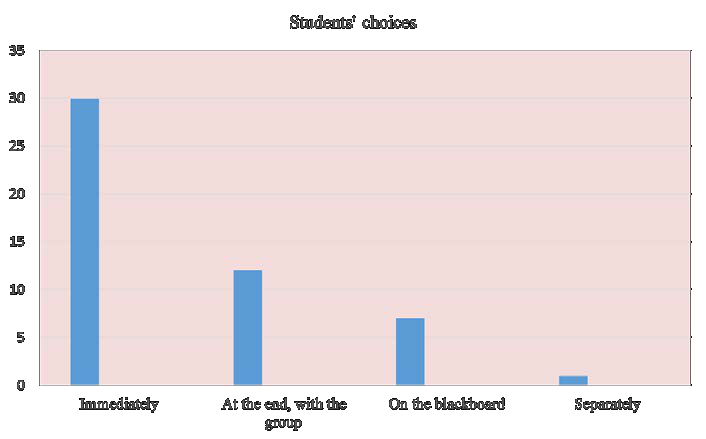

The last question directed to the students was: If you were to choose, while speaking how would you

coincides with the practice confessed by the teachers that is immediate error correction, and in

contradiction with what the specialists recommended. The other choices, at distance from the first one,

are: at the end, with the colleagues, explanations on the blackboard and 2 students chose separately.

Discussions

Even though this subject was approached in several studies in RFL, until this point we couldn’t

find a practical analysis on this matter, only a description of the recommended error correction methods

by the specialists. By our study we think we confirm these recommendations and furthermore we bring

the students’ point of view on this subject compared to the teachers’ one. A general observation we can

draw from our study regarding the questioned teachers is the fact that they are aware of what the

current theories are recommending. So, one teachers says: “we shouldn’t intervene immediately

because if we have an emotional student there is a big chance that he will stop and will not find the

courage to continue. That is why it is preferable to write down the errors and explain what isn’t correct

after his intervention is finished.” Another one declares: “it isn’t recommended to correct immediately

the mistakes, because we’ll make the student not to speak anymore”. And even knowing these

implications, they are still using more other ways of correction, as described in section

the least recommended technique, the immediate correction. On the other hand, we were able to see

that many of the students questioned don’t have a problem with this method, even more they find it

useful. But we should keep in mind that the responses were different, which shows us that the teachers’

intuition might have been right when using various error correction techniques in class. From the

results obtained we can say that in order to have better results during the speaking activities the

teachers should customize the method they use depending on the student in question. In our help comes

Harmer with a very interesting and efficient idea, from our point of view. He suggests that “perhaps the

best way of correcting errors in speaking activities appropriately is to talk to students about it. You can

ask them how and when they would prefer to be corrected; you can explain how you intend to correct

during these stages, and show them how different activities may mean different correction behaviour

on your part.” (Harmer, 2007))

Limitations and Further Research

From our analysis, we were able to see that the three opinions taken into discussion in this study

come and don’t come so much together. In what concerns the preferred method in error correction of

spoken productions, both the teachers and the students chose the immediate correction, which was

confusing taking into account the fact that the suggested one is the correction after the spoken

intervention, which was the second choice for both groups. The reason behind this option could be the

fact that all our subjects were adults, much more motivated. Another conclusion we can draw from here

is the fact that neither of the choice was unanimous, in any case there were subjects opposing to one

method or the other. This might suggest we need to talk to all the students in order to find the right

error correction method suitable for everyone, because learning a new language needs cosines.

We realize that the results of this study, for the moment are representative only for our university’s

situation, due to the small number of our subjects and cannot be considered as illustrative for RFL in

general. In order to confirm our findings and to make suggestions on the efficiency of one method or

the other a larger number of subjects is needed, from different universities.

References

- *** (2001). Common European Framework of Reference for Languages (CEFR). Strasbourg: Language Policy Unit.

- Bailey, K. (2005). Practical English Language Teaching: Speaking. New York: McGraw Hill.

- Brown, G. (1990). Listening to Spoken English. London and New York: Longman.

- Brown, G., Yule, G. (1984). Teaching the Spoken Language. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.

- Burlacu, D., Platon, E., Sonea, I. (2011). Procesul de predare/învățare a limbii române ca limbă nematernă (RLNM) la ciclul primar. RLNM: P1- ciclul primar. Cluj-Napoca: Casa Cărții de Știință.

- Harmer, J. (2007). The Practice of English Language Teaching. London: Longman.

- Lado, R. (1961). Language Testing. New York: McGraw Hill.

- Linse, C.T. (2005). Practical English Language Teaching. Young learners. New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Scrivener, J. (2005). Learning Teaching. A Guidebook for English Language Teachers. Oxford: Macmillan.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

04 October 2016

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-014-3

Publisher

Future Academy

Volume

15

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-1115

Subjects

Communication, communication studies, social interaction, moral purpose of education, social purpose of education

Cite this article as:

Arieșan*, A., & Vasiu, L. (2016). Error Correction. Case Study: Romanian as a Foreign Language (RFL) Speaking Activities. In A. Sandu, T. Ciulei, & A. Frunza (Eds.), Logos Universality Mentality Education Novelty, vol 15. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 77-85). Future Academy. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2016.09.10