Teaching Career-Oriented Majors in the English Language: Challenges and Opportunities (Kazan Federal University case study)

Abstract

Global education environment changes the function of the English language. Nowadays it acts not only as a means of learning but as a medium of instruction (EMI). As part of a study in Kazan Federal University, Institute of Management, Economics and Finance, we identified the gap between the requirements of a current global educational setting and the level of academics’ linguistic competence. This paper presents the results of academics’ current social portrait survey. During the survey we detected two major issues preventing the academics from teaching majors in English. The first concern is the lack of qualified English speaking academics capable of delivering courses in English (2%). The second considers the percentage of elderly teaching staff educated in the times of Soviet Union, when educational system concentrated upon communism construction and written translation was a dominating practice. The study applies qualitative methodology using a questionnaire designed with closed and open questions. We implemented Pearson correlation coefficient, Spearman's rank correlation coefficient and association index to identify the correlation between age, positions and language proficiency of academics and their desire to teach career-oriented majors in English. Though the teachers’ answers varied, they outlined the fact that the younger generation considers career-oriented major teaching using EMI to be an essential part in self-development and career progress. The older generation showed low interest in using EMI at their lectures and seminars. The findings also show that job position doesn’t affect the academics’ desire to be enrolled in EMI, while the level of their English proficiency influences the desire to teach the subject in English.

Keywords: English as a medium of instruction (EMI), teaching staff, career-oriented major, English language teaching program

1. Introduction

Global education environment changes the function of the English language. Nowadays it acts not

only as a means of learning but as a medium of instruction (EMI). EMI is usually defined as

implementation of the English language in the academic discourse in countries or states where the

majority of the population are non-native English speakers (Dearden, 2014).

It is worth mentioning that despite unequivocal necessity of EMI intake in academic environment in

non-English countries, their attitudes to this phenomenon appear far from homogenous. To illustrate

this, Italy and France has met it with fierce resistance, commenting that it violates the “freedom in

teaching” on the one hand, and “threats to the national language and an authentic French identity” on

the other (Phillipson, 2015). A number of Nordic countries reluct less against EMI implementation

although a great deal of concern has been expressed by national language councils and members of

cultural elite (Dimova et al., 2015).

Keeping these conditions in mind, it should be noted that little is known about the Russian

Federation in terms of EMI phenomenon despite it has always demonstrated a great concern for current

educational demands changes (Bagautdinova et al., 2016). Thus, operating under pressure of

globalization Kazan Federal University, being the largest higher education establishment in the Volga

Region of the Russian Federation, and receiving generous financial support for its development from

the government, is deeply involved in the process of internationalization (Bagautdinova et al, 2016).

The reasons underlying the trend include the importance of increasing academic mobility indicators as

well as the enhancement of the KFU image on the global education arena thus making the University

an attractive place for international applicants (Sungatullina et al., 2016). These goals are impossible to

achieve without changing the structure of the curriculum and the language of instruction. Therefore, the

issue of English as a lingua franca in ever-increasing competitive global tertiary educational setting is

acute and requires thorough consideration both at the administrative level and in the academic

departments (Fenton-Smith et al, 2015).

Hence, in this research paper we will be guided by the following research questions:

1.Do academics possess sufficient language proficiency and motivation to deliver professional

content in English?

2.What is academics’ attitude towards English in teaching majors?

2.Theoretical background

2.1.EMI at tertiary level

In the paper under research by English-medium instruction we understand the use of the English

language to teach academic subjects in countries or jurisdictions where the first language (L1) of the

majority of the population is not English (Dearden J. 2014). It is believed, that teaching the language,

or educational content, through the target language increases the amount of exposure the learners get to

it, and the opportunities they have to communicate in it, and therefore to develop their control of it

(Hafdís I. et al., 2015). What is more, it is a significant growth area, with over half of the world’s

international students, being taught in English, and universities offering an increasing range of courses

in this language (Graddol, 2006).

It is worth mentioning that EMI phenomenon as well as the term itself are relatively new for tertiary

environment worldwide (Flowerdrew et al., 1996). Thus, the question on how successfully it works is

still quite disputable.

According to the survey pursued under support of British Council, EMI is allowed more in private

institutions rather than in public ones (Dearden J. 2014). Besides, most faculties of higher educational

establishments are overwhelmingly unaware of EMI policies. They suffer from a written guidance on

how to teach within EMI framework (Mardanshina et al., 2014). Finally, most of institutions at tertiary

level tackle lots of questions about exams, namely, what language should they be in, or what is being

assessed, the English or the subject context (Tallón-Ballesteros, 2014).

Taking into consideration all these obstacles, it would appear that the EMI phenomenon is in a state

of flux (MahaEllili-Cherif, 2014). From country to country EMI is being promoted, rejected, refined

and sometimes even reversed (Dearden J. 2014).

2.2 Historical background of English language teaching in Russia

English language is a common lingua franca across the globe, which is currently affecting

diplomacy, commerce, culture, national language in addition to educational policies of a particular

country. It is useful to highlight in this regard that BrajKachru’s World Englishes model (Kachru’sBraj

B. 1991), where the expanding language circle is evidently becoming larger than that of inner and

outer, has already become axiomatic.

Russia is currently engaged in the modernization process of educational programmes and policies

throughout the country, where technologies and foreign languages are playing the leading roles. The

introduction of the second foreign language as a compulsory subject for secondary schools in Russia

denotes the fact that the government admits the necessity of foreign languages acquisition by the

younger generations. Frequently, children are exposed to language immersion even at an earlier stage,

while they are attending kindergartens, since the knowledge of a foreign language is considered to be a

symbol of prestige and high-rank.

Foreign language acquisition is an integral part of curricula in higher educational institutions (HEIs)

of Russia. The range of foreign languages presented at Russian universities differs depending on their

bias with English dominating in most cases (Ismagilova et al., 2014). A great urgency in the

involvement of universities into academic mobility programmes and international scientific

collaboration fosters HEIs to increase the duration of students’ exposure into the English language

(Galishnikova, 2014).Recently Institute of Management, Economics and Finance within KFU enlarged

the period of English teaching to Bachelor students from 198 classroom hours to 468 classroom hours

correspondingly. Thus, Russia is facing “English language boom”, which will gradually lead to the

extended number of potential academics mature both in core curriculum and English language likewise

(Zalyaeva et al., 2014).

However, educational language policy during the Soviet period of time deeply varied from the

modern one. Though the Soviet government introduced certain novelties into a foreign language

teaching in 1950s, the basis of the educational system was concentrated upon the ideology of

communism construction. All the texts implemented for educational purposes lacked authentic features

and couldn’t be used as a means for interaction, since they were isolated from their natural

environment. Moreover, the amount of students’ exposure into the English language acquisition was

relatively low (2 classroom hours per week for school leavers in 1961) and the emphasis was mainly

laid on English texts translation. Another challenge for English language acquisition was the

predominance of German language in most schools (80%), with only 12% of English at a secondary

level (Mirolyubov, 2002). As a result most students who got the education at that period of time were

deficient of speaking skills and possessed rather narrow vocabulary.

With the Soviet Union collapse in 1990s, educational language policy improved immensely.

Progressive methods accompanied with modern educational facilities were introduced into the system

of secondary and higher education. Nevertheless a great layer of the population, including academics

employed in the structural unit under discussion, who were born and acquired education in the Soviet

Union are incompetent in the English language speaking, have a serious gap in the knowledge of this

language or have certain fears about using it as a means of delivering a lecture to students.

3.Methodology

The researchers have undertaken a quantitative and qualitative study in the English Language

proficiency of the teaching staff. One hundred and fourteen academics from KFU, namely the Institute

of Management, Finance and Economics, participated in the online English-language proficiency test

as well as the oral interview conducted by the English language academic department staff. The on-line

test checked the reading and writing skills, whereas the interview was intended for checking speaking

and listening skills. Ten highly qualified English language professionals conducted the interview and

ranged the teaching staff into 5 broad groups in accordance with the Common European framework of

references (CEFR) A1–C1.

The interviewees have also participated in a sociological research, where they answered open and

closed-ended questions and revealed their experience of using English language in the classroom, their

own perception of the language proficiency level as well as their expectations and fears of teaching and

learning in English. Basing on the respondents’ answers we divided them into 5 broad groups in

accordance with age and their positions in the institute.

We implemented Pearson correlation coefficient to identify the correlation between age, positions

and language proficiency of academics and their desire to teach career-oriented majors in the English

language. Spearman's rank correlation coefficient (RCC) served as a tool for assessing how well the

relationship between two variables can be described.

4.Results

The authors implemented Spearman RCC (p) and Student's t-test (t-test) to identify the relationship

between the variables: X1 (age), X2 (job position), X3 (level of English proficiency) and Y (the

academics’ desire to teach majors using EMI). This coefficient revealed the extent of statistical

dependency and its trend:

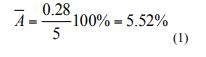

The approximation error (Ā) is 5-7% which signifies the high level of formula fitting to the

benchmark data:

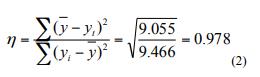

Empiric correlation ratio (ŋ), we applied, serves as a tool for measuring the extent of dependency

between X1 and Y:

The value received indicates the fact that the younger the teacher is the more ambitious he/she is

about teaching majors using EMI.

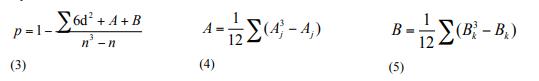

The Spearman RCC emphasized that the dependency between the job position (X2) and the desire to

teach majors using EMI (Y) is weak or even insignificant. We obtained the values from the following

equations:

where j – number of bindings to variable X2, Aj – amount of similar ranks to variable X2, k –

number of bindings to variable X2, Bk – amount of similar ranks to variable Y. To verify the results of

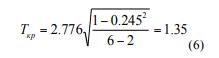

our calculations we implemented Student's t-test and obtained the following:

To define the dependency between the level of English proficiency (X3) and the desire to teach

using EMI (Y) we used the same equations and revealed the values given below:

As we can see that p is lower than t-test meaning that the rank correlation coefficient is insignificant

and the dependency between the variables do exist but weak.

5.Discussion

Given that the present study questions the idea of academics’ sufficient language proficiency and

motivation to deliver professional content in English, the key points put in the questionnaires

concerned their background, experience, level of language and desire to teach majors in English as well

as their attitude to EMI training applicability. The core respondents’ audience included teachers under

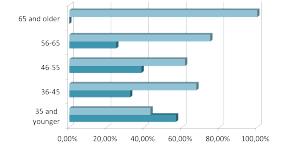

35 (see Figure 6):

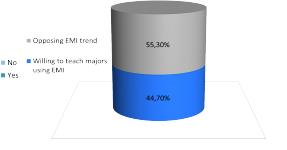

As we can see from the chart (see Figure 7), 44.7% of respondents reveal their positive attitude to

teach majors in English whereas 55.3% oppose the trend. The matter is connected with the fact that the

overwhelming majority of respondents (more than 50%) belong to the under 35 years age group born

after 1980s when the significant changes in the state foreign language policy resulted in the improved

attitude of schools and youth to linguistic proficiency. Thus, academics under 35 demonstrate greater

willingness and openness to any tertiary education innovations due to globalization including using

English as a medium of instruction.Hence, we can observe a strong connection between the academics’

age and their desire to educate in the English language.

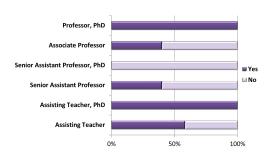

In contrast to a heavy dependency between age and desire to use EMI in teaching, there is no

correlation between academics’ job position with the latter issue (see Figure 8). On the one hand, this

observation could be determined by unwillingness of elderly teaching staff (who predominately hold

Professors’ and Associate Professors’ positions) to adopt to modern educational changing policies; on

the other hand, young teachers (holding Assistant Professors’ and Senior Lecturers’ positions) who are

rather flexible and able to think critically do not see any incentives to alter their teaching philosophy

either.

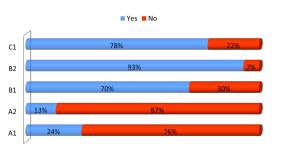

We should note that the respondents’ appreciation of EMI for teaching majors does not mainly arise

from their level of English proficiency (see Figure 9). It means that teachers’ linguistic literacy does

not increase the desire to practice EMI training. The case is explained by the lack of linguistically

proficient students regardless teachers’ language competence.

During the survey the respondents emphasized motivational and demotivational factors for EMI

training. Motivational factors include the English language level and academic mobility opportunities

improvement; increase of one’s own professional competence and competitiveness in the international

educational market; acquiring of valuable experience; opportunity to use authentic materials; expanded

research connections.

Demotivational factors comprise low level of the English language awareness of both teachers and

students; prevalence of students who are linguistically illiterate; the curriculum of the major is

structured in accordance with Russian Federation requirements and is not applicable internationally;

Increase of the work load; feedback decreasing due to increased complexity of learning materials for

students.

6.Conclusions

The divergence in academics’ answers demonstrates that EMI in language teaching shapes out in

multifaceted and largely unfamiliar situations and needs to be studied in detail in order to enhance the

quality of language teaching at tertiary level. On the one hand, it is determined by instructors’ linguistic

insecurity due to their age or job position; lack of methodological base or students’ insufficient English

knowledge. On the other hand, the appreciation of EMI for language teaching as the way of attracting

multilingual and multicultural audiences gives hope that the challenges can be turned to opportunities

based on such values as friendly atmosphere, increased cultural awareness as well as maintaining and

sharing of tolerance.

References

BagautdinovaNailya G., GorelovaYuliya N.&Polyakova Oksana V. (2015). University Management: From

Successful Corporate Culture to Effective University Branding. Procedia Economics and Finance, 26, 764-768.

BagautdinovaNailya G., GorelovaYuliya N.&Polyakova Oksana V. (2016). University economists training under global educational environment: challenges and prospects.SHS Web of conferences, 26.01042, ERPA 2015. DOI: 10.1051/shsconf/20162601042 DeardenJ. (2014). English as a Medium of Instruction – a growing global phenomenon, 8-29. Retrieved from https://www.britishcouncil.org/sites/default/files/e484_emi_-_cover_option_3_final_web.pdf DimovaS., Hultgren A. K.&Jensen Ch. (2015). English-medium instruction in European higher education: Review and future research in Dimova S., Hultgren A.K. and Jensen Ch. (Eds.), English-Medium Instruction in European Higher Education (pp.317-325). English in Europe, 3.

DrljačaMargićBranka&Vodopija-KrstanovićI. (2015). Introducing EMI at a Croatian university: Can we bridge the gap between global emerging trends and local challenges? inDimova S., Hultgren A.K. and Jensen Ch. (Eds.), English-Medium Instruction in European Higher Education (pp.43-65). English in Europe, 3 Fenton-Smith B.& Gurney L. (2015).Actors and agency in academic language policy and planning, Current Issues in Language Planning, Retrieved from DOI: 10.1080/14664208.2016.1115323.

FlowerdrewJ.&Miller L. (1996). Lecturer perceptions, problems and strategies in second language lectures. RELC Journal, 27, 23-46.

Galishnikova Elena M. (2014). Language Learning Motivation: A Look at the Additional Program. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 152, 1137-1142.

Graddol D. (2006).English next, 81-100. British Council.

HafdísI.&ArnbjörnsdóttirB. (2015). English in a new linguistic context: Implications for higher education in Slobodanka D., Hultgren A.K. and Jensen Ch. (Eds.), in Dimova S., Hultgren A.K. and Jensen Ch. (Eds.), English-Medium Instruction in European Higher Education (pp.137-157). English in Europe, 3.

IsmagilovaLiliya R.&Polyakova Oksana V. (2014). The Problem of the Syllabus Design within the Competence Approach based on the Course “English for Master Degree Students in Economics (Advanced Level)”. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 152, 1095-1100.

KachruBraj B. (1991). World Englishes and Applies Linguistics. 178-205 MahaEllili-Cherif (2014) Integrated language and content instruction in Qatar Independent schools: teachers’ Retrieved from perspectives, Teacher Development, 18, 2, 211-228.

DOI: 10.1080/13664530.2014.900819.

Mardanshina Rimma&ZhuravlevaEvgenia (2014). Model of Complementary Linguistic Education for Economists.Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 152, 1091-1094 Miroluybov A.A. (2002). The history of the Russian foreign language teaching methodology, 15-26. Selection and peer-review under responsibility of the Organizing Committee of the conference

Phillipson R. (2015). English as threat or opportunity in European higher education in Dimova S., Hultgren A.K. and

Jensen Ch. (Eds.), English-Medium Instruction in European Higher Education (pp.19-43). English in Europe, 3.

SungatullinaDilyana D., Zalyaeva Ekaterina O.&GorelovaYuliya N. (2016). Metacognitive awareness of TOEFL

reading comprehension strategies. SHS Web of Conferences, 26.01046, ERPA 2015. DOI:

10.1051/shsconf/20162601046

Tallón-Ballesteros J. Antonio (2014). An experience on Content and Language Integrated Learning in University lessons of Operating Systems in the Computer Science Area. HEPCLIL (Higher Education Perspectives on Content and Language Integrated Learning). Vic, 159-170. Retrieved from http://dfelg.ua.es/acqua/publicaciones/susana/hepclil.pdf Zalyaeva E.O.&Solodkova I.M. (2014). Teacher-student Collaboration: Institute of Economics and Finance Kazan Federal University Approach. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences,152, 1039-1044.

PTIONS, PROBLEMS AND STRATEGIES IN SECOND LANGUAGE LECTURES

JOHN FLOWERDEW AND LINDSAY MILLER

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

20 July 2016

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-011-2

Publisher

Future Academy

Volume

12

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-451

Subjects

Teacher, teacher training, teaching skills, teaching techniques, organization of education, management of education, FLT, language, language teaching theory, language teaching methods

Cite this article as:

Sungatullina, D. D., Zalyaeva, E. O., & Gorelova, Y. N. (2016). Teaching Career-Oriented Majors in the English Language: Challenges and Opportunities (Kazan Federal University case study). In R. Valeeva (Ed.), Teacher Education - IFTE 2016, vol 12. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 396-403). Future Academy. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2016.07.63