Abstract

The present study assesses the wellbeing potential of material and experiential purchases among a group of Tomsk consumers. Four hypotheses are tested. 1) “Consumer preferences differ by age, gender, income level, education” turns to be confirmed; 2) “Purchases of gifts make people more happy than buying for themselves” demonstrated not very stable and weak correlation; 3) “Money spent on material purchases are perceived as a better decision than spent on experience” shows not very strong and statistically not significant correlation. 4) “Experiential purchases lead to more happiness” had no evidence to be proved. Further research is needed to investigate the phenomena more accurately.

Keywords: wellbeingmaterial and experiential purchaseshappinessspendingdecision-making

Introduction

People often spend part of their discretionary income on goods or services that give them happiness (Pchelin & Howell, 2014; Christopher, Saliba & Deadmarsh, 2009; Kasser, Cohn, Kanner & Ryan, 2007). Their consumption includes material and nonmaterial goods which influence wellbeing in different ways. For example, Pchelin & Howell (2014) propose that purchasing life experiences and material items leads to dissimilar results. They conclude that buyer’s expectation of life experiences result in more well-being, but it is believed that material items are a better use of money. However, a large body of research suggests that we frequently make wrong assumption on what kind of purchase will actually contribute more to our wellbeing (Chancellor & Lyubomirsky, 2011). A common debate, both among us as shoppers as well as among scientists (Millar & Thomas, 2009; Guevarra & Howell, 2014), focuses on whether material or experiential purchases lead to more happiness and wellbeing.

At first the nature of material and experiential purchases should be brought to light. As a rule material goods are tangible; a consumer can move them from place to place, they last beyond a couple of days, and they take up physical space, a tangible object that can be kept in one’s possession. Experiential purchases usually are connected with an event that is finite in time (Nicolao, Irwin & Goodman, 2009). In experimental condition material purchases are represented as stereos, cars, houses, clothes, shoes, jewellery etc.; movies, journey, parks, and restaurant dinners are examples of experiential ones. Even though it is hard to distinguish them in theory; some researchers (Van Boven & Gilovich, 2003; Nicolao, Irwin & Goodman, 2009) believe that consumers can discriminate between these two types of purchases. One of the practical criterion for distinction may be “purchases made in order “to have” for material items and “purchases made in order “to do” for life experiences (Kumar, Killingsworth & Gilovich 2014). The level of adaptation to experiential purchases is lower compared to material purchases (Nicolao, Irwin & Goodman 2009).

But for purchases which bring negative emotions experiences and material goods have the same impact on wellbeing (Van Boven & Gilovich, 2003), sometimes material purchases are even less unpleasant as they may be used as a gift or as a stock for future consumption.

The fundamental reasons of difference in effect of material and experiential purchases on wellbeing have very complicated nature which is not fully discovered yet.

For instance, Deighton (1992) suppose that there is a difference in level of attention, participation and performance in the consumption process of these goods.

Van Boven and Gilovich (2003) stated the reason why the pleasure out of experiential purchases is longer. They found that experiential purchases induce “mentally revisiting” much more frequently than material purchases. Another reason is that waiting for experiences brings more pleasure than waiting for possessions. Moreover, consumers can derive utility from anticipation itself, and its value is greater for experiential purchases.

Howell & Hill (2009) suggest another reason. When the basic needs are met the significant increase in wellbeing may be achieved only by fulfillment of higher-order psychological needs; and it is experiential purchase that helps to do this. Also experiential purchase decreases social comparison which sometimes is rather destructive for wellbeing.

There are some researches on foreign national data reflecting the particularities of wellbeing from material and experiential purchases for different socio-demographic groups. For instance, paper of Van Boven & Gilovich, 2003 shows that preference of experiential purchase declines with age, female will more likely be buyers of experiential goods, and experiential goods are more preferable with the increase of income.

So in the presented paper we try to test these statements on Tomsk region’s data.

Hypotheses

The present study assesses wellbeing potential of material and experiential purchases among a large group of Siberian shoppers. A specific goal of our study is to include older adults and compare the results we obtain for younger and older adults.

At the beginning we made some suggestions which created a basis for hypotheses testing. For the first hypothesis (H1) the rationale was the following.

Some research results (Pchelin & Howell, 2014) showed that social and demographic characteristics did not impact results. But in another study (Dunn & Weidman, 2014) respondents with low levels of income and education report that their material purchases made them more happy than experiential purchases. Consequently, we tried to check how social and demographic characteristics influence purchasing behavior.

So the hypothesis H1 can be formulated as “Consumer preferences differ by age, gender, income level, education.”

Another hypothesis (H2) includes the idea represented in papers (Aknin at al, 2013; Hill & Howell, 2014) which assume that when a person spends money on others and makes gifts it brings more pleasure than spending money on himself. And the second hypothesis was put as “

The rationale for the next hypothesis (H3) is that very often possession perceived as a better use of money than experience (Christopher, Saliba & Deadmarsh, 2009; Chancellor & Lyubomirsky, 2011; Dunn & Weidman, 2014; Dunn, Gilbert & Wilson, 2011). For Russian buyers we wanted to estimate whether it is a case. The statement of H3 is “

And the last assumption of our research (H4) is connected with spending on social relationship. In particular, experiential purchases enhance social networking and bring more emotions (Nicolao, Irwin & Goodman, 2009; Pchelin & Howell, 2014; Gilovich, Kumar & Jampol, 2014). So H4 is put as “

Method

We invited participants in our research using two main ways:

i) By interviewing shoppers face to face at shopping centers, right after they made a purchase (N=108). We included both relatively upscale centers as well as open markets, and shopping areas that attract older buyers (N=45).

ii) By recruiting people in social networks (N=127) and contacting them online.

The median age was 35.15 (SD=17.8), 72% were females, with 73% of participants belonging to the middle class.

Materials and procedures

Subjective wellbeing is measured by five questions (OECD, 2013). A Likert scale was used to measure overall life satisfaction (“Overall, how satisfied are you with life as a whole these days?”, where 0 means respondents feel “not at all satisfied” and 10 means they feel “completely satisfied”). Another question concerned the value of things and deeds in respondent’s life (“Overall, to what extent do you feel the things you do in your life are worthwhile”, where 0 means things are “not at all worthwhile”, and 10 means “completely worthwhile”). Respondents were also interviewed about their emotional state on the previous day. We asked about how they feel yesterday happy, worry and depression, where 0 mean they did not have such feelings “at all”, but 10 means they felt it “all of the time”.

Then participants told about their recent purchase and the purchases they think positively about more often in last six month, specifically how much these purchases contributed to their happiness and to what extent they felt the purchase was a good use of the money (on 7-point Likert scale). Finally they were approached some demographic questions.

Results

The results are somewhat surprising in what they seem to indicate. In contrast to the prevailing opinion (Pchelin & Howell, 2014) there is little difference in wellbeing between material and experiential purchases.

Demographic and social parameters of purchases are shown in Table

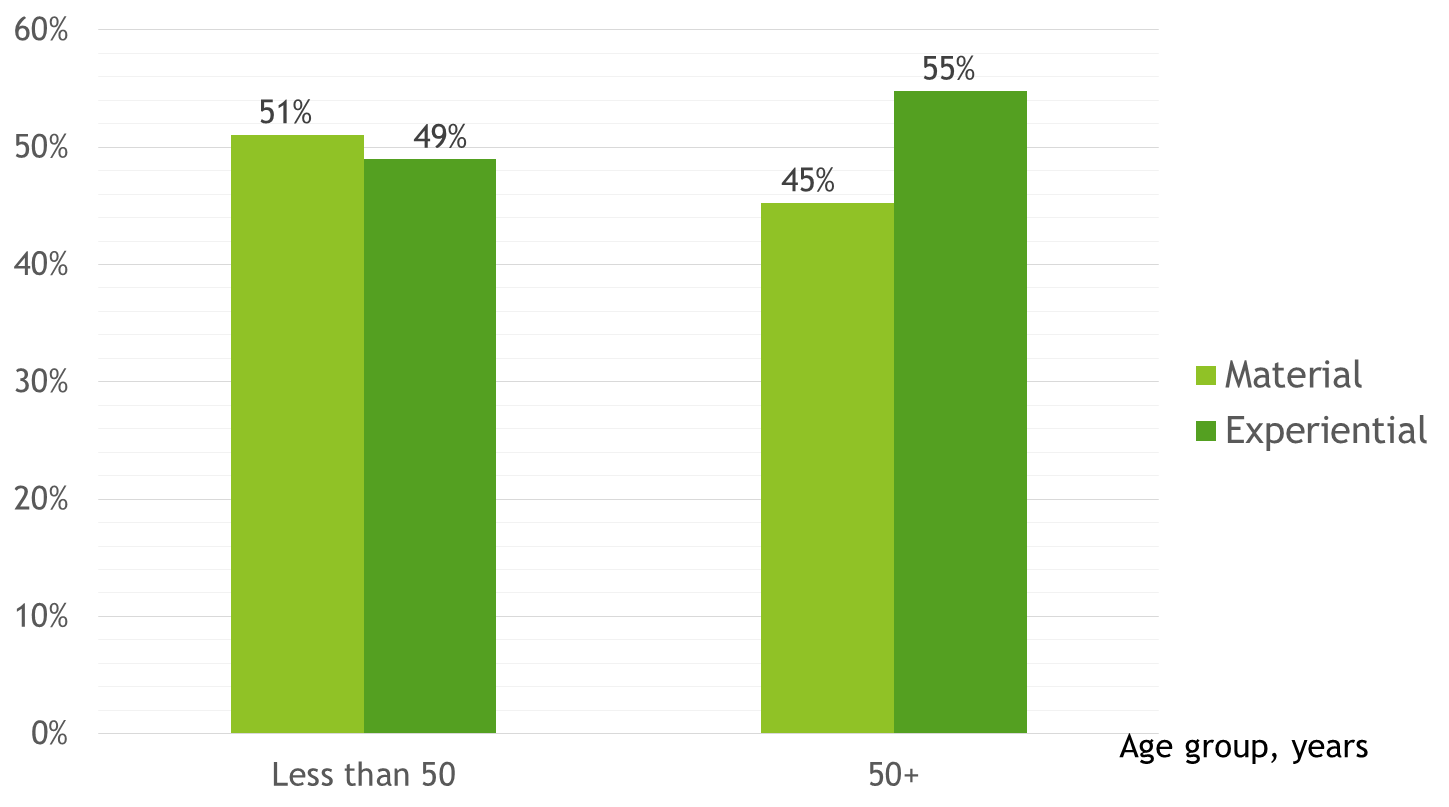

According to the data of our survey it should be noted that young adults prefer more material purchases, whereas, in contrast, older adults prefer experiential purchases (fig.1).

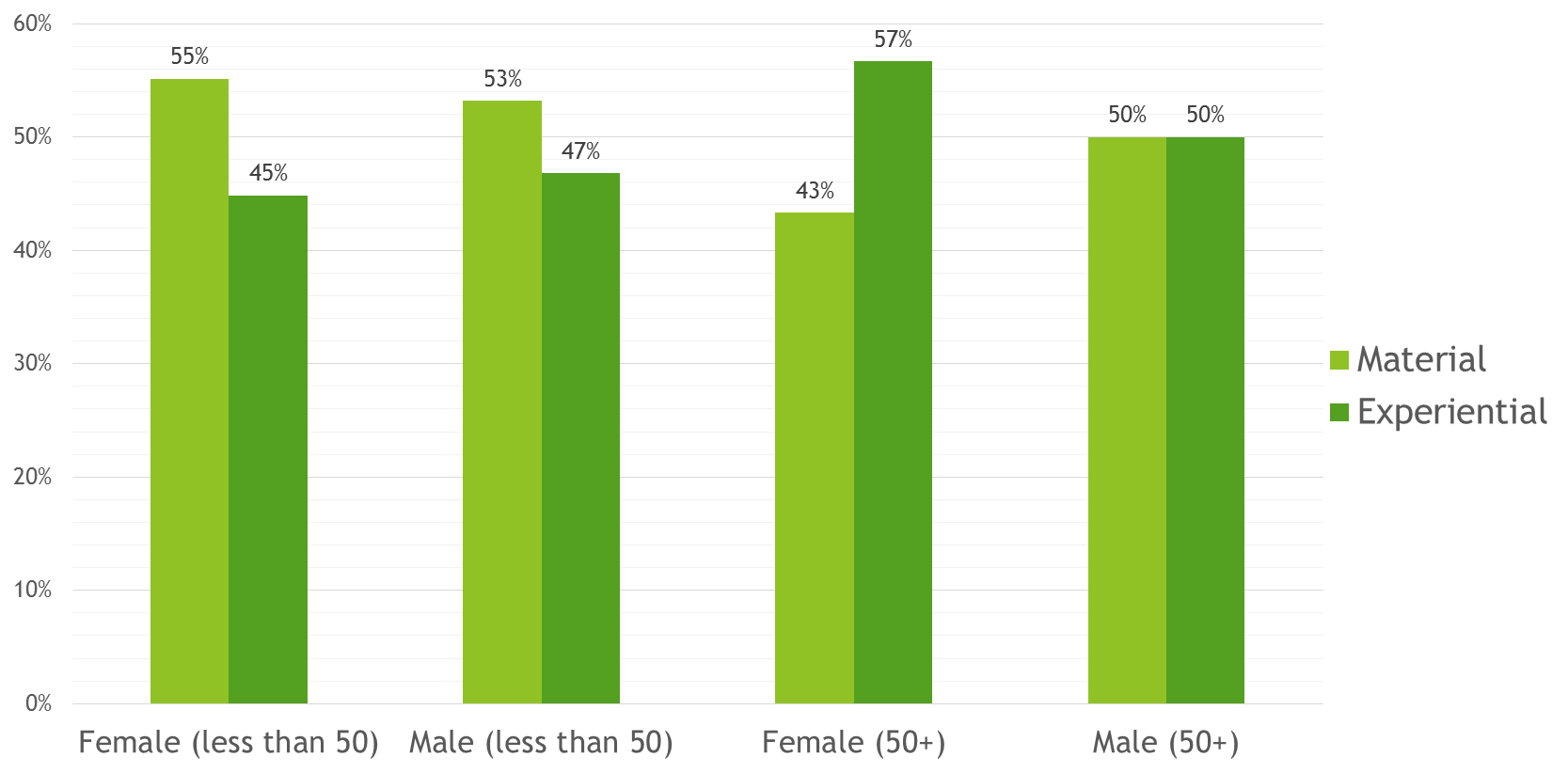

Interestingly, males and females under the age of 50 prefer material purchases, but females over 50 prefer experiential purchases. For men over 50 material purchases bring the same satisfaction as experiential purchases (fig. 2).

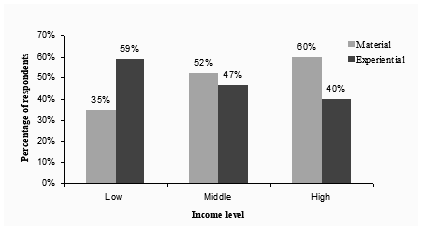

It should be noted that people with low income prefer experiential purchases more (fig.3) and this preference declines with income increase. There is a statistically significant correlation (Spearman's correlation coefficient rs=0.53) between 1) to what extent people feel the purchase is a good use of the money and 2) an expectation about purchases.

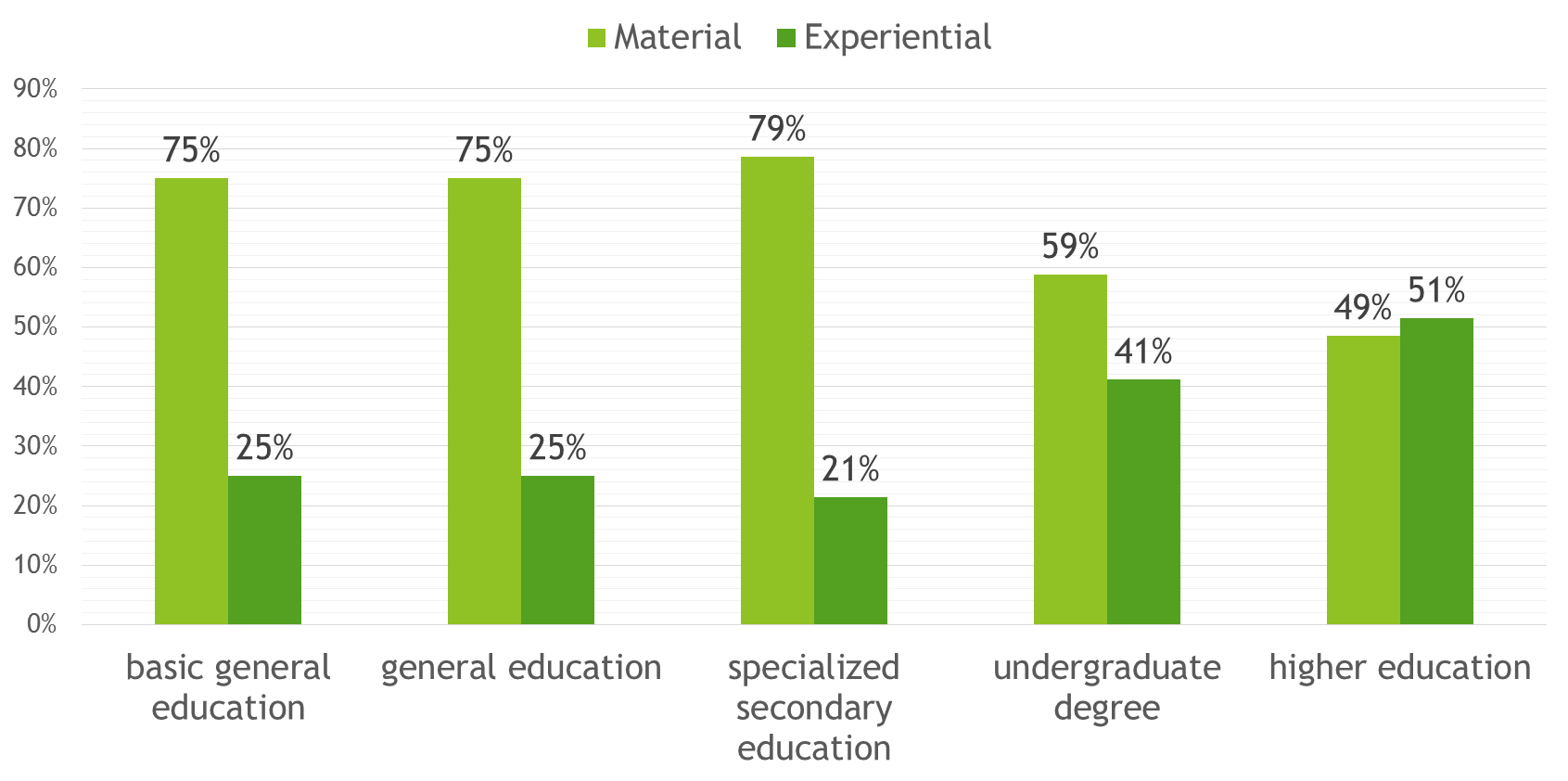

There is also a correlation between education and preferred type of purchase. People who have higher educational prefer experiential purchases more (fig. 4). The relationship is statistically significant but rather weak (rs=0.12).

Thus Н1 may be considered as confirmed. There is a relationship between type of purchases and social and demographic characteristics of respondents.

Hypothesis H2 was put as “Purchases of gifts bring more happy than buying for yourself”. We measure the correlation between two things. The first one is how much these purchases contributed to respondent’s happiness (on 7-point Likert scale), where 0 means respondents feel “not at all happy” and 7 means they feel “very happy”. The second reflects whether a person bought a good for yourself or for a gift. During the test this hypothesis we wanted to check the level of pleasure from shopping for yourself or for a gift. It turned out that there is a weak correlation between the level of happiness of the purchase and its type (rs = 0.11, p<0.05).

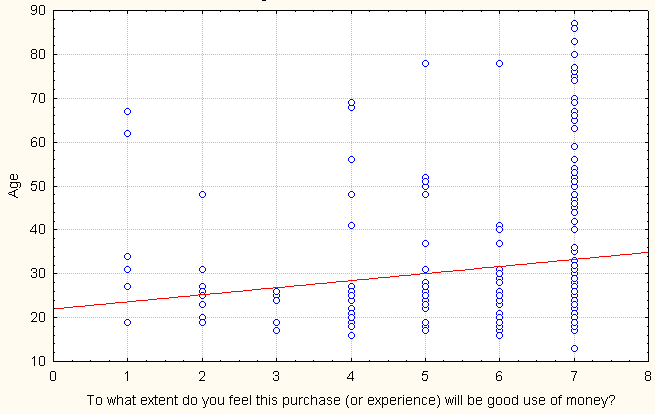

Hypothesis H3 tested whether consumers evaluate buying material goods as the best use of money. During the survey respondents answered the question “How useful is the purchase in terms of the use of money?” It is worth noting that older participants assessed the purchase as the best use of money (fig. 5). But again the correlation is not very strong and statistically not significant (rs = 0.14, p<0.05).

Horizontal – To what extent do you feel this purchase (or experience) will be good use of money? (on 7-point Likert scale), where 0 means respondents feel “not at all good use” and 7 means they feel “very good use”.

Table

Mean differences in wellbeing for material and experiential purchases are shown in Table

The above table shows the results of the survey in two modes: "face to face" and in social network. It should be noted that for people whom we ask “face to face” were more positively in their estimations. For hedonic wellbeing (participants answered the following question: ‘How much do you expect this purchase will contribute to your overall life’s happiness?) estimates are higher for “face to face” mode and for experiential purchases. Subjective wellbeing was measured by the following questions: “Overall, how satisfied are you with life as a whole these days?”, “Overall, to what extent do you feel the things you do in your life are worthwhile?”, “Do you happy?” Respondents who gave answers through social network evaluated subjective well-being from experiential purchases higher.

Unfortunately H4 was not confirmed. According to the results of the survey we have not been established statistically significant relationship between the level of happiness and experiential purchases.

3. Discussion

In the study we tested the four hypothesis in order to show connection between the type of shopping and the well-being both for younger and older consumers.

An analysis of the data obtained in the survey in "face to face" and the social network modes has been established that the experiential purchases are preferred by people: 1) over the age of 50; 2) with low incomes; 3) with higher education. The greatest satisfaction our respondents receive from purchases for gift-giving. During the "face to face" survey respondents rate material purchases as the best use of money. At the same time, however, we have not obtained statistically significant results between the level of happiness and experiential shopping.

In order to obtain more reliable results about these phenomena it is necessary to conduct additional research. First of all there should be more large sample. In order to deeply understand discrepancies between forecasts and evaluations, future research should include longitudinal studies (as discussed in Howell & Guevarra, 2013).

Acknowledgement

This work was performed by the authors in collaboration with Tomsk Polytechnic University under the Agreement No.14.Z50.31.0029

References

- Aknin, L. B., Dunn, E. W., Whillans, A. V., Grant, A. M., & Norton, M. I. (2013). Making a difference matters: Impact unlocks the emotional benefits of prosocial spending. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 88, pp. 90–95. doi:

- Chancellor, J., & Lyubomirsky, S. (2011). Happiness and thrift: When (spending) less is (hedonically) more. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 21(2), pp. 131–138. doi:

- Christopher, A. N., Saliba, L., & Deadmarsh, E. J. (2009). Materialism and well-being: The mediating effect of locus of control. Personality and Individual Differences, 46(7), pp. 682–686. doi:

- John Deighton. The Consumption of Performance Journal of Consumer Research Vol. 19, No. 3 (Dec., 1992), pp. 362-372

- Dunn, E. W., & Weidman, A. C. (2014). Building a science of spending: Lessons from the past and directions for the future. Journal of Consumer Psychology. In press, Corrected Proof, Available online 3 September 2014. doi:10.1016/j.jcps.2014.08.003

- Dunn, E. W., Gilbert, D. T., & Wilson, T. D. (2011). If money doesn’t make you happy, then you probably aren't spending it right. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 21(2), pp. 115–125. doi:

- Gilovich, T., Kumar, A., & Jampol, L. (2014). A wonderful life: experiential consumption and the pursuit of happiness. Journal of Consumer Psychology. In Press, Corrected Proof, Available online 19 September 2014. doi:

- Guevarra, D. a., & Howell, R. T. (2014). To have in order to do: Exploring the effects of consuming experiential products on well-being. Journal of Consumer Psychology. In Press, Corrected Proof, Available online 2 July 2014. doi:

- Hill, G., & Howell, R. T. (2014). Moderators and mediators of pro-social spending and well-being: The influence of values and psychological need satisfaction. Personality and Individual Differences, 69, pp. 69–74. doi:

- Howell, R. T., & Hill, G. (2009). The mediators of experiential purchases: Determining the impact of psychological needs satisfaction and social comparison. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 4(6), pp. 511–522. doi:

- Howell, R. T., & Guevarra, D. A. (2013). Buying Happiness: Differential Consumption Experiences for Material and Experiential Purchases, pp. 1–24.

- Kasser, T., Cohn, S., Kanner, A. D., & Ryan, R. M. (2007). Some Costs of American Corporate Capitalism: A Psychological Exploration of Value and Goal Conflicts. Psychological Inquiry, 18(1), pp. 1–22. doi:

- Kumar, A., Killingsworth, M. a, & Gilovich, T. (2014). Waiting for Merlot: anticipatory consumption of experiential and material purchases. Psychological Science, 25(10), pp. 1924–31. doi:

- Millar, M., & Thomas, R. (2009). Discretionary activity and happiness: The role of materialism. Journal of Research in Personality, 43(4), pp. 699–702. doi:

- Nicolao, L., Irwin, J. R., & Goodman, J. K. (2009). Happiness for Sale: Do Experiential Purchases Make Consumers Happier than Material Purchases?, 36(August), pp. 188–198. doi:

- Guidelines, O., & Measuring, O. N. (2013). Question modules Module A: Core measures, pp. 253–265.

- Pchelin, P., & Howell, R. T. (2014). The hidden cost of value-seeking: People do not accurately forecast the economic benefits of experiential purchases. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 9(4), pp. 322–334. doi:

- Van Boven, L., & Gilovich, T. (2003). To do or to have? That is the question. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85(6), pp. 1193–202. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.85.6.1193

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

20 February 2016

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-006-8

Publisher

Future Academy

Volume

7

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-513

Subjects

Social welfare, social services, personal health, public health

Cite this article as:

Kashapova, E., Ryzhkova, M., Gustap, N., & Nikitina, S. (2016). Purchases and Wellbeing of Older and Younger Adults in Tomsk. In F. Casati (Ed.), Lifelong Wellbeing in the World - WELLSO 2015, vol 7. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 415-423). Future Academy. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2016.02.53