Abstract

Problem statement: The topic of motivation in therapy has received considerable attention; little of this attention, however, has yielded relevant and concrete information as to how should therapists motivate their clients in order to help them achieve their goals. Research questions: How does the therapist, through his verbal behavior, try to improve the odds of the client’s doing their appointed tasks or homework? Purpose of the study: As part of an ongoing research program in verbal interaction in therapy, our aim is to adequately describe, in technical and operating terms, what is the therapist really doing when he/she intends to motivate the client for a given course of action. Research method: using the SISC-INTER-CVT in-session verbal behavior coding system, 88 sessions were studied and their motivational utterances classified according to their structure and their inferred function as elements in a behavior sequence. As a result of this process, a motivational utterances coding system (SISC-MOT) was developed, and all frequencies and proportions of the different types of motivational utterances were analyzed. Findings: The therapist does not issue motivational utterances in a random fashion; rather, he/she adapts their form and function to the clinically relevant activities that predominate in a given session.Conclusion: Motivational utterances as defined in this study can be a powerful resource in the clinician’s endeavor to help the client achieve his/her goals if used properly. Helping the client anticipate the positive consequences of changing his/her behavior is of paramount importance, but doing it in the right moment and form is what really makes a difference.

Keywords: process research, therapy, verbal behavior, motivation

Introduction

Motivation has always been a central -and controversial- research topic in Psychology. When defined in its most naïve, non-technical way, the reason is apparent: it would seem that understanding why people do the things they do would be a matter of paramount interest not only to psychologists, psychiatrists and other mental health professionals, but to most everyone. “Motivation” is a word that is used very often, in a wide variety of contexts and with a vast array of different meanings. This has, paradoxically, made its research a singularly complex endeavor: all research must begin with a clear definition of the object of study, and this overabundance of competing definitions makes it almost impossible to find a single definition that will be universally accepted, even by psychologists.

In this paper, we will assume a radical behaviorist approach to the study of motivation in therapy; listing the reasons for doing so far exceed the purpose of this study. The interested reader will find an in-depth discussion of the matter in Froján, Alpañés, Calero & Vargas (2010), and also in Michael (1993) and Laraway, Snycerski, Michael & Poling (2003). Motivation is defined, in this context, as the operations that are performed prior to particular behavior that somehow alter the likelihood of its occurrence or its strength or duration, be it by altering the evoking potential of discriminative stimuli, by allowing (or impeding) the behavior itself or by enhancing or reducing the effectiveness of consequent stimuli. A prime example of a motivational operation would be food deprivation, which both increases the discriminative potential of food-related stimuli and its reinforcing strength.

When speaking about clinical practice, however, we need to take into account the verbal frame of behavior; deprivation does not only happen with prime, biological necessities but rather one can be deprived of things such as human contact, happiness or simple tranquility. In therapy, then, motivational operations involve the anticipation of “the good things to come” if the client complies with the therapist’s recommendations, and, of course, the lack of change –and therefore the continuous suffering- that would follow should the client refuse to comply.

The objective of this study is to clarify how does a behavior therapist motivate his/her client, by analyzing the frequency and type of his/her motivational utterances using observational methodology. Our hypothesis is that the therapist does not issue motivational utterances at random, but rather adapts them to the clinically relevant activiy he/she is engaging in. In order to achieve this objective, a broad sample of clinical sessions was studied and, through the use of observational methodology, all motivational utterances issued by the therapist were classified into categories that would allow for the kind of analysis needed, as will be addressed in the next section.

Method

Sample

For this study, 88 recordings of clinical sessions were used. These all pertained to a sample collected in the Instituto Terapéutico de Madrid (henceforth “Itema”), and were part of 9 different clinical cases treated by 8 behavior therapists with varying degrees of expertise. All sessions were individual and all clients were adults.

Instruments

The SISC-CVT and clinically relevant activities

The SISC-CVT is a coding system that takes inspiration from Pérez’s basic behavioral operations (Pérez, 1996) to try and classify every verbalization uttered in-session according to its possible function. These possible functions –or rather, topographies- are as follows: reinforcement, punishment, discriminative, evocative, informative, instructional, motivational and other. The reasons why this kind of instrument is so important are obvious: a moment-to-moment analysis of the clinical interaction can yield useful information as to how must a therapist behave in order to achieve the best possible results. It also offers a solid point from which to analyze a factor that has received quite a lot of attention with very little of this attention ending up in useful or solid findings: the clinical relationship. Rather than conceptualizing this relationship as a function of the client and therapist’s personal variables, we think it more fruitful to define it as the product of clinical interaction: a continuous stimulus-response chain in which the therapist’s verbal behavior has a discriminative and consequent stimulus function, while the client’s verbal behavior is considered to have a response function. The reason behind this is the directive style of behavior therapy; the therapist evokes and discriminates the client’s behavior by asking questions, and reinforces or punishes the client’s behavior in a process that might very well be considered a shaping of the desired verbal and non-verbal responses. In order to do so, the therapist will always be in control of what happens in therapy, be it the topic of conversation or the order in which all topics will be discussed. The interested reader will find more information regarding the SISC-CVT in Ruiz (2011), Froján, Calero, Montaño & Ruiz (2011) and Froján-Parga et al. (2008).

In order to better comprehend the process of change that the client undergoes when in treatment, this research group used this coding system to divide the whole therapy into four groups of sessions that shared a common theme, a clinically relevant activity that prevailed when taking into account the relative frequencies and durations of the therapist’s verbal behavior. The interested reader will find all information in Ruiz (2011), but we summarize here, for the sake of simplicity, the main characteristics of the four groups: -Group 1: Evaluation. This group is characterized by the abundance of therapist utterances aimed at gathering information.

-Group 2: Explanation. The sessions in this group include comparatively high frequencies of those therapist’s utterances that aim to communicate the clinician’s technical knowledge to the client, in order for him/her to understand the mechanisms that underlie his/her problem.

-Group 3: Treatment. This group has high frequencies of those utterances by which the therapist instructs the client to perform certain tasks that will improve his/her situation.

-Group 4: Consolidation. In this group, the therapist uses his speech to ensure the client will be able to utilize what he/she has learned and generalize it to other areas of his/her life.

It must be kept in mind that these groups do not necessarily follow a chronological order, although that might seem the intuitive way to understand it. In fact, a group 2 session might appear between two group 3 sessions, or vice versa. It is the therapist’s verbal behavior what will define each session as part of one of the four groups, and not the moment in which it happens.

The SISC-MOT-T

In an effort to put the focus on the motivational utterance, a new coding subsystem was created, aimed to the clarification of the motivational processes that happen in the course of therapy. This new subsystem would have to expand on the different kinds of motivational utterances that the therapist uses, analyzing their content but, mostly, their function. As previously discussed, behavior analysis considers “motivation” to be the operations that are performed prior to the actual happening of a behavior that somehow affect it, be it by strengthening it in a variety of ways (such as making discriminative stimuli even more potent, making the response feasible or augmenting the reinforcing potential of consequent stimuli) or by weakening it (by making discriminative stimuli less effective, turning the behavior itself into something harder or diluting the reinforcing potential of consequent stimuli). Considering that approach, it is easy to see

why the motivational utterance was defined in the SISC-CVT the twofold way it was: as an utterance that anticipated the consequences of a particular course of action for the client or, alternatively, an utterance that seemed to have a “motivational intent” in its colloquial sense (encouraging verbalizations such as “I’m sure you will make it”).

The development of the new subsystem started with the informal viewing of the recorded sessions by two independent observers, in order to get a broad idea of how motivational utterances were used. After this, and through discussions with experienced therapists, a first draft of the category system was created. This first version was used in the analysis of ten sessions, with both observers coding all of them independently. After this process was complete, solutions were implemented for the shortcomings of this early version; the process was repeated until the coding system accounted for all the possible variations of the motivational utterance and the inter-rater agreement reached acceptable levels (more specifically, a mean kappa level of 0,86, considered excellent according to Bakeman, 2000 and Landis & Koch, 1977). The final categories from the SISC-MOT-T are presented here in an abridged version for the reader’s convenience, with brief definitions for all the different categories in which the motivational verbalization was divided.

- Colloquial motivational utterances: those that the therapist uses with the apparent intention of encouraging or uplifting the client in his/her change process in general. An example would be as follows:

- Chain motivational utterances: those that clearly specify a contingency regarding the client’s behavior in the

future. It must be classified in four different dimensions: mode of the response (by action vs. by omission), discriminative context (specific vs. general), value of the consequent stimulus (apetitive vs. aversive) and stimulation variation (by withdrawal/non-occurrence or by occurrence). Some examples: o Therapist: If you smile and say “hello” to your sister-in-law every time you see her, your relationshipwill improve. (chain motivational utterance, specific context, response by action, apetitive consequent by occurrence) o Therapist: It will never change if you don’t start making the effort of thinking differently. (chainmotivational utterance, general context, response by omission, aversive consequent by non-occurrence) o Therapist: If you stop attacking her every time she gets sad, she will stop being so picky with you.

(chain motivational utterance, specific context, response by omission, apetitive consequent by withdrawal) o Therapist: You have to keep on practicing every evening, and you’ll soon start to feel better. (chainmotivational utterance, specific context, response by action, apetitive consequent by occurrence).

Procedure

These recordings had been analyzed in previous studies using the Observer XT, a software by Noldus that allows the researcher to code each individual behavior in a given video or audio file. All verbal behaviors, both by the therapist and the client, were coded in accordance with the SISC- CVT coding system, as previously described.

Once the coding system was fully developed and the inter-rater agreement reached an optimal level as previously described, the entire sample of 88 sessions was reviewed and the motivational utterances were classified in accordance with the SISC-MOT-T by the two previously mentioned independent observers (one of them s primary observer, the other to ensure inter-rater agreement levels remained in excellent levels) trained in the use of the system.

Afterwards, descriptive statistical analyses were performed in order to comprehend the differences in the use of all motivational utterances. All mean contrasts were performed using non-parametric tests, since the Kolmogorov-Smirnov and Levene tests indicated that all variables used did not fulfill the homocedasticity and normality hypotheses.

In order to study how the motivational utterance changes depending on in which group it is uttered, descriptive

statistics were calculated for each of its possible variations.

All statistic calculi were performed using the SPSS 15 software.

Results

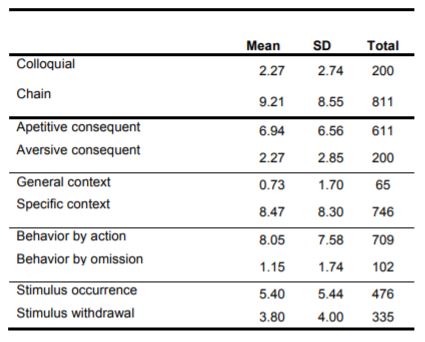

Below (see figure 1), the results of the descriptive analyses performed are showed. Mean and standard deviation are

calculated per session.

The abundance of chain motivational utterances over the colloquial utterances is immediately conspicuous, as is the equally large primacy of the apetitive consequent, specific context, behavior by action and stimulus occurrence modifiers over their respective counterparts.

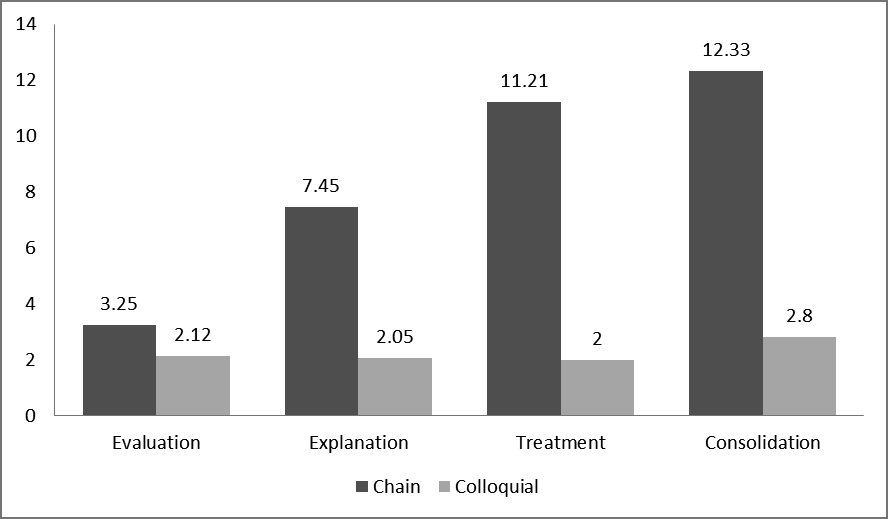

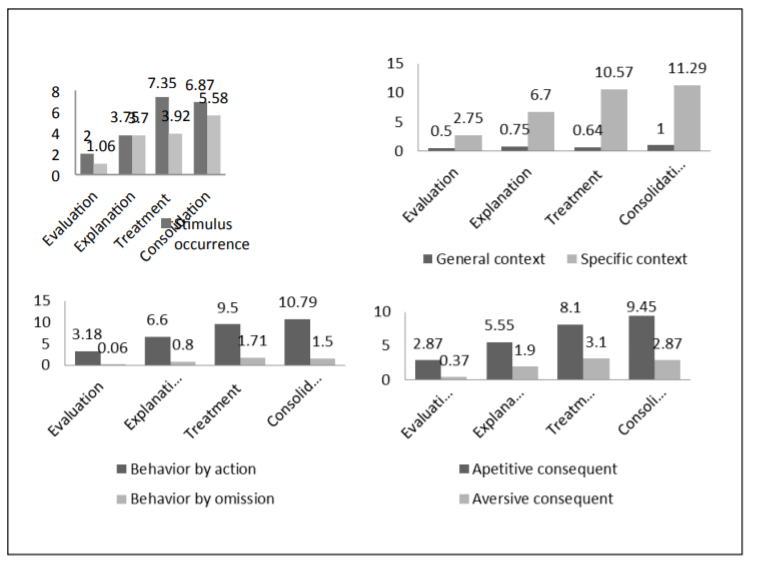

In figures 2 and 3 the results of the descriptive analyses per clusters are displayed.

As can be seen, there is a clear increase in frequency of all motivational utterances, being cluster 1 the one with a lowest frequency of chain motivational utterances and cluster 4 the one with the highest. Few types experience a decrease, but the aversive consequent dimension actually increases in cluster 3, as does the behavior by omission dimension.

Discussion

Given the now proven fact that the therapist does not use all motivational utterances interchangeably, it is time to try and find an explanation to that phenomenon.

The differences themselves are not unexpected: every clinician with some degree of experience would have been able to predict that all possible variations on the motivational theme are not used equally. The real information lies in the different rates of all modifiers: it would seem, were we to extract a “prototypical” motivational utterance, that it would follow the chain-action-specific-apetitive-by occurrence scheme. This is, of course, the therapist trying to make the client anticipate a desirable outcome of a particular course of action that he/she wishes the client to undertake.

In more detail: -Regarding the apetitive/aversive dichotomy: it is considered to be far better to use apetitive control (i.e., using reinforcement or the anticipation of reinforcement as a means to control a subject’s behavior) than aversive control. The reasons for this far exceed the intent and depth of this study; suffice it to say that apetitive control is easier to perform and does –most often- not provoke any form of contra-control. Also, it can have an uplifting effect on the client, who will be able to anticipate the good things that will result from his/her actions. Very often, the client is faced with the need to perform a particular task that will require of him/her to do something that he/she has been avoiding or is in some way loath to do. Anticipating a desirable outcome, such as an improvement of a currently grievous situation or the occurrence or appearance of things the client wants seems like a sound strategy. That is not to say that the anticipation of aversive consequences does not have its uses: for example, it could come in handy when the client perseveres in his/her noncompliance with a specific homework assignment or refuses to follow a course of action that the therapist deems essential. But perhaps it’s precisely this narrow spectrum of situations in which it makes sense to use them the reason why they are so seldom uttered. After all, it would seem you can’t go wrong when anticipating a good outcome (provided, of course, that you have good reason to expect a good outcome from a particular course of action), while perhaps anticipating aversive consequences would in some way make the client less enthusiastic about the therapeutic process.

-Regarding the general context/specific context dichotomy: the fact that most chain motivational utterances clearly specify a concrete context in which the contingency will be expectable might have much to do with the results-oriented, practical style of behavior therapy. This kind of treatment puts an emphasis on the tasks (or homework assignment) that the client must perform in order for his/her situation to improve. These tasks must be made in a specific way, and hence it is very important to be very clear about what must the client do; the fact that anticipating consequences for his/her actions is most often coupled with a concrete stating of the moment or context in which that apetitive or aversive contingency will be in force could simply be the way that the therapist tries to make it more likely for the client to perform the required task. General context motivational utterances, on the other hand, might be being more used in the final part of the therapy, in which it is of paramount importance that the client generalizes what he/she has learned to other settings and contexts, although the analyses performed in this study do not include that dimension.

-Regarding the behavior by action/by omission and stimulus occurrence/withdrawal dichotomies: it might be tempting to attribute this difference to the fact that sentences that deal with action do not usually require a complicated phrasing and are more straightforward than those that deal with not-action. Also, when striving to be perfectly understood, it is preferable to use simple sentences. But we think that, again, the main reason for this difference is not that the sentences might be easily understood, but that the contingencies expressed in them are clear enough. The same goes for the occurrence/withdrawal dichotomy: a sentence that clearly refers to what will happen will simply be more often used than one that refers to something that will not happen. The difference between these two opposites, though, is smaller than it is in other cases; this might be a consequence of how often a clinician must allude to the pain or suffering that will no longer be there (that will be withdrawn) if the client abides by his/her instructions.

-Regarding the chain/colloquial dichotomy: while the colloquial utterances might have its uses (indeed if they didn’t they would not be uttered), they have a fundamental difference with chain motivational utterances, which is that, by their very structure, they are often used in response to the client’s expressions of doubt or, alternatively, enthusiasm. Given that the therapist might be aiming, when he/she motivates, to make compliance more likely, it is quite sensible that he/she tries to convey an instruction within the motivational utterance (“if you do X, Y will happen” is, after all, a complex, more relevant form of “do X”) in order to make it more attractive for the client to follow the instruction. Hence it is perhaps the less concrete, less instruction-driven form of the colloquial utterance what makes them not be as often used as chain motivational utterances.

-Regarding the distribution of motivational utterances in the different clusters: it is clear from this results that the clinician does not use all different motivational utterance types equally often. Even more interestingly, the therapist seems to adjust the type of motivational utterance he/she is using to the clinically relevant activity he/she is engaging in. For example, we see that in the first session group (evaluation), chain motivational utterances and colloquial motivational utterances appear almost as often, while in the rest of the clusters there is great disparity in their frequencies. It stands to reason that when the therapist is evaluating, he/she is not trying to persuade the client to act in any particular way, hence the low frequency of chain motivational utterances, whose primary purpose is precisely to set a specific contingence that will follow a particular behavior by the client. In the same way, we see that both aversive consequent and behavior by omission levels are highest in the third cluster (treatment). This can be sensibly explained by the fact that, when treating, the clinician must face non-compliance by the client. It could be that this is the moment the therapist has the most need of warning the client that bad things will happen if he/she doesn’t do a particular thing. As for the fact that general context contingencies are –although admittedly scarce- most frequent in the explanation and consolidation groups can very well be a consequence of the fact that it is in these groups that the therapist most talks about what happens always and for all people, be it because he/she is explaining how psychological processes work, or because he/she is striving to make the client aware that what he/she has learnt throughout the therapeutic process is applicable to other aspects and in other moments of his/her life.

We have previously alluded to the behavior therapist as a directive, controlling professional, who leads the client into the process that will allow him/her to reach the therapeutic goals that were agreed; in this type of therapy, for the clinician to use all resources at his/her disposal to give the client that extra impulse towards change does not come across as strange: rather, it is to be expected. It seems that the motivational utterance, as defined in the SISC-CVT and further detailed in the SISC-MOT-T, can be a key feature of the therapist’s speech. Also, it appears that, when a therapist wants to motivate, he/she most likely uses sentences that go along the lines of “if you do this in this specific way and moment, something that you want or like will happen”.

As for the improvements that could be made in order to make this study more complete and detailed, a few ideas could be as follows:

- Broadening the sample might yield more varied and generalizable results.

- Comparing samples of inexperienced therapists with samples of experienced therapists would be of enormous interest; after all, experience might have shaped the motivational utterances that expert therapists use into a better, more useful form.

- Lastly, including therapists from different therapeutic perspectives would undoubtedly be interesting

References

Bakeman, R. (2000). Behavioural observation and coding. In H. T. Reis & C. M. Judd (Eds.), Handbook of research methods in social and personality psychology (pp. 138-159). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Froján-Parga, M. X., Montaño-Fidalgo, M., Calero-Elvira, A., García-Soler, A., Garzón-Fernández, A., & Ruiz-Sancho, E. (2008). Coding system for the therapist’s verbal behavior. Psicothema, 20, 603-609.

Froján, M.X., Calero, A., Montaño, M. & Ruiz, E.M. (2011). An approach to the functional study of verbal interaction between therapist and client throughout the therapeutic process. Clínica y Salud, 22(1), 69-85. doi: 10.5093/cl2011v22n1a5

Landis, J. R. & Koch, G. G. (1977). The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics, 33, 159-174.

Laraway, S., Snycerski, S., Michael, J., & Poling. (2003). Motivating operations and terms to describe them: some further refinements. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 36. 407-414

Michael, J. (1993). Establishing operations. The Behavior Analyst, 16, 191-206.

Pérez, M. (1996a). Psychotherapy from a behaviorist’s standpoint. Madrid: Biblioteca Nueva.

Ruiz, E. (2011). A functional approach to the study of verbal interaction in therapy. Unpublished doctoral thesis, Universidad Autónoma de Madrid, Madrid, España.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

14 May 2014

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-000-6

Publisher

Future Academy

Volume

1

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-236

Subjects

Social psychology, collective psychology, cognitive psychology, psychotherapy

Cite this article as:

Verdu, M. R. D. P., Frojan-Parga*, M. X., Moreno, D., & Cruz, I. V. D. L. (2014). Motivational Utterances in Behavior Therapy: How Do We Motivate Our Clients?. In Z. Bekirogullari, & M. Y. Minas (Eds.), Cognitive - Social, and Behavioural Sciences – icCSBs 2014, vol 1. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 77-86). Future Academy. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2014.05.10