Abstract

The electronic monitoring device to monitor offenders was implemented in August 2015 in Malaysia. It serves to assist the offender to re-entry into the community where it allows the offenders to have more contact with family members and maintain their employment. However, these offenders would normally face problems re-entry into the community due to social stigma and negative association the community has with regards to the offenders wearing an electronic tagging to mingle with the community. This study investigates the community readiness towards the implementation of electronic monitoring to offenders in the most developed state in Malaysia. Face-to-face interviews that involved the civilian and the electronic monitoring device project stakeholders were conducted. The interview questions were adopted from Tri-Ethnic Center Community Readiness Handbook by Colorado State University. The findings of this research show the community's readiness stage level has resulted at Stage 6: Initiation. It is also recommended that in-depth study of the community readiness is essential to identify the gap of the electronic monitoring device implementation, improve existing efforts and identify key factors for the success of the electronic monitoring device implementation.

Keywords: Community readiness, electronic monitoring device, offender monitoring

Introduction

Electronic tagging is surveillance that uses an electronic device, fitted to a person. An electronic monitoring device (EMD) could be attached to an offenders’ ankle or wrist to track their whereabouts (Belur et al., 2020). EMD also has been used in healthcare settings for people with dementia. It is also being used as a special device that monitor and track the self-quarantine control of patients at their home using radio frequency-based identification technology (RFID) and global positioning systems (GPS) (Utusan Malaysia, 2021). EMD is now a permanent fixture in criminal justice systems across the world and is an integral and growing part of the criminal justice system (Hucklesby & Holdsworth, 2020). It is used extensively across Europe, the Americas and Australia variously as a condition for bail; as part of a community sentence or suspended sentence orders or to allow for the early release of prisoners. EMD also has been increasingly used internationally with recent implementation for those convicted of domestic violence offenses (Hwang et al., 2021). During the COVID-19 pandemic, the Brazilian government used EMD to Brazilian prisoners as a strategy to prevent the spread of infection in prisons (Xavier et al., 2021). The aims of using EMD are many and varied from reductions in time in custody, thereby allowing governments to reduce costs by providing cheaper alternatives to prison. EMD technology has advanced over time. Initial systems in the 1980s were only able to determine whether a tagged offender had strayed beyond a certain distance from their home. The move from radio frequency (RF) technology to more sophisticated monitoring using GPS began in the 1990s, monitoring offenders over much greater distances and at any time of the day, which constantly records the location of the offender in almost real-time (Belur et al., 2020).

From time to time, EMD implementation will help practitioners and policymakers to better understand how it can be used most effectively to achieve the best outcomes. Usually, EMD technology comes in the form of an electronic tag that is fitted to a person’s ankle with three main types; each with different capabilities: RF, GPS and transdermal alcohol monitoring (sobriety tags). RF tags enable the monitoring of someone’s confinement to a specific location, and an alert is raised if they go out of range. GPS tags track a person’s precise location in almost real-time and are not specific to an address. Sobriety tags detect alcohol levels in the wearer’s sweat (Fitzalan Howard, 2020)

The first two types of technology enable location monitoring; RF technology facilitates the remote monitoring of whether or not wearers are in a particular indoor location and is deployed almost exclusively to monitor curfews. RF technology is cheap, reliable, and easily understood but only monitors wearers’ presence in specific indoor locations. The devices signal when wearers leave and return to the monitored address but not where they go. Meanwhile, GPS monitors the movements of wearers continuously and in real-time. GPS technologies have a much greater range and can be used to monitor wearers indoors and outdoors (Hucklesby & Holdsworth, 2020). If the device is based on GPS technology, it is usually attached to a person by a probation officer, law enforcement or a private monitoring services company field officer, and is capable of tracking the wearer's location wherever there is the satellite signal to do so. Electronic monitoring tags can be also used in combination with curfews to confine defendants or offenders to their homes as a condition of bail, as a stand-alone order or as a form of early release from prison.

The recent introduction of GPS technologies, and the use of EMD as a mechanism to reduce prison use during the Covid-19 pandemic all signal that EMD will play a significant role in the future of the criminal justice system. The monitoring of offenders with electronic devices, which can be used to pursue various goals, was originally introduced in the United States to counteract prison overcrowding. Operating under the premise that EMD is less punitive than imprisonment, policymakers soon introduced EMD as an intermediate measure. Thus, EMD became an inherent part of the sanctioning systems of many countries (Meuer & Woessner, 2018).

Electronic Monitoring Device

In Malaysia, EMD was implemented in August 2015 until current based on agreement (Perjanjian KDN/PL/PDRM/21/2015). It was approved by the Ministry of Home Affairs (KDN) and Royal Malaysian Police (PDRM). The use of EMD on offenders will reduce the cost of detainees' expenses in prison and foster a sense of prevention among detainees and would-be criminals. Special procedures relating to electronic monitoring devices are stated in the Prevention of Crime Act 1959 (The latest amendment made by 1st September 2015). The total number of wearers in Malaysia is 2620 as reported on 10 May 2020 (Ministry of Home Affairs, 2021).

The process of EMD assigning is based on the court’s order. There is a two-tier system of dealing with violations or breaches of electronically monitored curfew orders. More serious violations result in immediate breach action and include being absent during a whole curfew period or a significant part of it, damaging or tampering with equipment, and physical assaults. Less serious violations do not result in immediate breach action but warning letters are issued. These include being absent for short periods during curfew times (time violations) or tampering with, or minor damage to, monitoring equipment. Less serious violations are accumulated until breach action is taken which is instigated when either two violations have occurred or when time violations have accumulated to a certain level. It is possible, therefore for offenders, fail to comply in several ways without being formally breached.

The PDRM generates a standard operation procedure (SOP) on implementing EMD monitoring against risk offenders where they commit a crime based on law. These offenders will be monitored through the system by their device tagged on their leg and the type of crime includes, pickpockets, snatches, gang involvement, wilderness, drug dealers, and people who are capable of threatening public safety (Prevention of Crime Act (POCA). EMD implementation is one of the techniques that has been taken by PDRM to ensure the repeated crime activity decreases within the same suspect. EMD monitoring is tagged to an offender or suspect who is released from the prison to avoid them committing another crime. Besides that, each movement of the wearers will be monitored, and the parole officers will be updated on their daily location, activity or behaviour. These help the PDRM to observe and to decrease the chance for the offenders to break the law or commit a crime.

Community Readiness Model

Community readiness is defined as the level at which individuals and groups are willing to accept and support the implementation of new programs or activities in the community. It also has been succinctly defined as the extent to which a community is adequately prepared to implement a prevention program. Community readiness is problem-specific, highlighting the need for assessing readiness levels separately for each issue targeted by the community (de Oliveira Corrêa et al., 2020).

Several studies of the Community Readiness Model (CRM) have been carried out to verify the importance of the CRM which was developed to help in measuring a community’s readiness level on several dimensions that will help diagnose where efforts are needed. It has also been able to identify the communities’ weaknesses and strengths, as well as the obstacles and threats. Information derived from the studies could be used to develop strategies to improve the community readiness levels (Liu et al., 2018; Nwagu et al., 2020)

CRM has been widely applied in behavioural changes at the community level. It can be tailored to a particular issue, based on input from local experts, and provides scores for five related dimensions namely: (a) community knowledge of efforts; (b) community climate; (c) community knowledge about the issue; (d) leadership; and (e) resources. The CRM assumes that communities are at different stages of readiness in addressing an issue, and interventions can be developed based on assessed readiness to address the issue (Liu et al., 2018). The research studied the level of readiness, acceptance, and knowledge of community towards EMD implementation, as well as the community knowledge on efforts of PDRM to observe and to reduce the number of offenders who break the law or commit a crime.

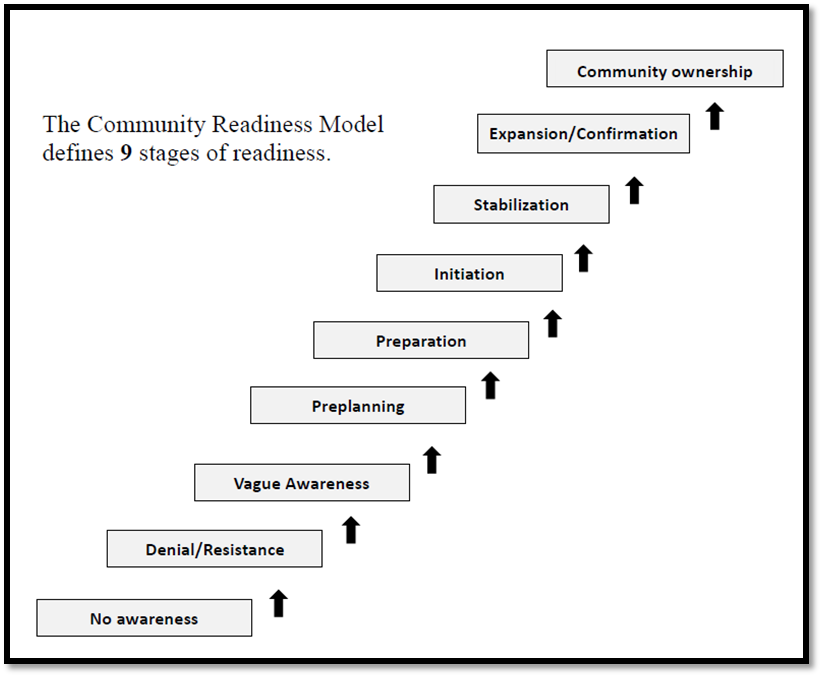

This research adopted the CRM from Tri-Ethnic Center Community Readiness Handbook, which has been introduced in 2014. The model implemented has found helpful because of the following reasons: it is an inexpensive and easy-to-use tool; it encourages the use of local experts and resources; provides both a vocabulary for communicating about readiness and a metric for gauging progress; helps create community-specific and culturally-specific interventions; and it can identify types of prevention/ intervention efforts that are appropriate (Tri-Ethnic Center Community Readiness Handbook, 2014). There are nine stages proposed by the model; (1) the community has no knowledge about local efforts addressing the issues while the leadership members believe the issues is not rely much of a concern; (2) the leadership and community members believe that this issue is not a concern in their community, or they think it can’t or shouldn’t be addressed; (3) few community members have at least heard about local efforts but know little about them while leadership and some community members believe that this issue may be a concern in the community; (4) some community members have at least heard about local efforts but know little about them while leadership and few community members acknowledge the issue and believe something has to be done to address it; (5) most community members have at least heard about local efforts and the leadership is actively supportive of continuing or improving current efforts or in developing new efforts; (6) most community members have at least basic knowledge of local efforts and the leadership plays a key role in planning, developing and/or implementing new, modified, or increased efforts; (7) most community members have more than basic knowledge of local efforts and the leadership is actively involved in ensuring or improving the long-term viability of the efforts to address this issue; (8) most community members have considerable knowledge of local efforts, including the level of program effectiveness and strongly supports efforts, while the leadership plays a key role in expanding and improving efforts; and (9) most community members have considerable and detailed knowledge of local efforts, highly supportive and actively involved in the efforts while its leadership is continually reviewing evaluation results of the efforts and is modifying financial support accordingly. Figure 1 shows the Community Readiness Model adopted in this study.

This research was conducted with the intention to study at what stage the community readiness towards the implementation of electronic monitoring devices to offenders in Malaysia, is at. This study is significant as the readiness for the community to accept the offenders wearing the EMD into the community play an important role. The research aimed at getting information regarding the level of community readiness towards EMD implementation to offenders in Malaysia.

Problem Statement

According to KDN (2018), electronic monitoring devices for offenders has been implemented since 2015 with 2576 offenders in Malaysia. Electronic monitoring does not physically restrain a person in prison as it allows the offenders to have more contact with family members and maintain employment (Kucharson, 2006). It could also serve to assist offender re-entry into the community and there is some evidence that drug and/ or sex offenders on electronic monitoring are more likely to complete treatment than other (non-tagged) offenders, who might be related to better re-offending outcomes (Belur et al., 2020). Moreover, few researchers claimed that electronic monitoring devices could reduce the time in custody, thereby allowing governments to reduce costs by providing cheaper alternatives to prison (Belur et al., 2020; Garland 2002, Hucklesby & Holdsworth 2020). Hence, KDN and PDRM implemented the electronic monitoring device to reduce the number of offenders placed in prison. This move is seen as one of the ways to overcome the logistics issues of offenders’ placement. However, the civilians neither know about the electronic monitoring device implementation, nor aware of the offenders with electronic monitoring devices roaming in the community. Based on Gansefort et al. (2018), the community readiness concept applies a stage-based behaviour change model to the community level. It suggested that a certain degree of problem awareness and pre-planning in the community is necessary for the electronic monitoring device to be implemented successfully. This caused the employer reluctant to hire the electronic monitoring device wearer (Crump et al., 2017). Therefore, it is a must to assess the stage of community readiness towards electronic monitoring device implementation in Malaysia. In addition to that, there has been limited research done regarding community readiness towards electronic monitoring device implementation especially in Malaysia. Thus, there is a need to investigate the stage of community readiness towards the implementation of electronic monitoring device to offenders in Malaysia.

Research Questions

Based on the problem statement described in the previous section, this study answers the following research questions:

What is the scenario of electronic monitoring device implementation in Malaysia?

What are the community’s readiness towards electronic monitoring device implementation in Malaysia?

Purpose of the Study

This study investigates the community readiness towards the implementation of electronic monitoring to offenders in Malaysia. It involves the interviews with parole officers, an employer who gave a job to the offender and also the citizen or public. The findings provide a foundation for the interested parties, such as the policy makers and enforcement agencies to further investigate the readiness issues. The outcome could also be utilized by the interested parties in making plan for further actions needed to be taken in the implementation strategy of EMD and how the offenders could be able to re-entry into the community safely.

Research Methods

This study consisted of three (3) main phases: define issues and community; data collection and analysis; and finding and conclusion. Sub-section below discusses in detail the activities of each phase.

Define Issues and Community

The Department of Statistics Malaysia reported 42.4% of the total index crimes occurred in the states of Kuala Lumpur and Selangor in 2016-2017. While in 2018-2019, the crime index ratio per 100,000 population of Kuala Lumpur (592.3) and Selangor (304.3) remains the top of the chart. Thus, the implementation of electronic monitoring devices is seen to reduce the number of offenders placed in prison due to space issues and cost-effective alternatives to prison. Therefore, this study was based in the state of Selangor.

The key stakeholders are: PDRM, offenders, offender’s employer and civilian. These individuals, with their knowledge and understanding, will be providing insight on the nature of EMD implementation. Based on the Tri-Ethnic Center Community Readiness Handbook, a minimum of 6 key respondent interviews are sufficient. The key respondents’ profile is as in Table 1.

Data Collection and Analysis

This phase consists of instrument design, interviews, and data analysis. The questions during the interviews were phrased clearly to make them understandable. All interview questions were adopted from Tri-Ethnic Center Community Readiness Handbook (2014). In general, the set of questions were mostly open-ended, and the guideline started with introductory questions that covered general information about the respondent, as it was necessary to cultivate a good understanding of the community group. Careful attention was paid during the interviews to identify any subjects of readiness. Transcripts of each interview were then transcribed to proceed with the analysis of the data. The interview questions were divided into five dimensions of the readiness key factors that influence the community’s readiness to act on EMD implementation in Malaysia. The five dimensions identified and measured in the Community Readiness Model are very comprehensive in nature. Table 2 presented the dimensions, number of questions asked for each dimension and the main issues addressed by the questions.

Mapping Readiness Scores

Understanding the scoring process is very important to ensure the accuracy of findings in adapting this readiness model. This phase involved mapping Individual Scores, Consensus Scores and Overall Community Readiness scores. It helps to picturize the stage of the community readiness towards EMD implementation in Malaysia. The survey questions are organized for each of 5 dimensions of community readiness. Each answer to the interview question is scored accordingly and this will later indicate the readiness level for each dimension. The first step is to map the Individual Scores for the 6 interviews from civilians and public authority. Secondly, calculate the average of the Consensus Scores for each dimension across all the interviews. Finally, calculate the Overall Community Readiness Score using the following formula:

Overall Community Readiness = add the 5 Consensus score of for each dimension / 5

Findings

This section describes the findings of the study conducted involving six separate interviews with two types of respondent groups which are: the authority agency; and the public. Two PDRM officers - representing the agency - were interviewed. The public was represented by three civilians and one employer of EMD wearers. They are the key respondents of the qualitative interviews because they have first-hand knowledge about the community and the electronic monitoring supervision scenario. Apart from that, the variety of participants bring different viewpoints with diversity in perspectives about electronic supervision technologies, therefore more data are likely to be gathered.

Community Readiness Mapping Stage

The first group of the respondents was referred to as public (civilian). This interview focused on three respondents covered in Selangor state, one from the outskirts area and two of them from the town area. The fourth respondent was the offender’s employer who has one EMD wearer works under his employment. This employer has been interviewed in another outskirt area where he has a car wash business with six workers including the EMD wearer. The second type of the respondent was referred to as Authority Agency where three respondents who have direct contact with EMD offenders were interviewed. Two respondents were PDRM officers in Selangor. One of the police officers is attached with the Selangor Police Contingent Headquarters and the other one was attached with the Police District Headquarters. Table 3 shows the analysis of the interview.

In Table 3, #P1, #P1, and #P3 refers to the public or the civilian. While #E1 refers to an employer where one of the staff is the offender in parole and wearing EMD. The total scores of these data shows the level of community readiness is at Stage 5: Preparation. The Stage 5: Preparation represents that most of the community members have at least heard about implementation of EMD to offenders in Malaysia. At the same time, the local community leadership is actively supportive of continuing or improving current EMD implementation. For example, almost all respondents mentioned that the PDRM has deployed efforts towards public safety and is supported by the community leaders. The attitude in the community is “Community members have basic knowledge about causes, consequences, signs and symptoms of the EMD implementation. Two respondents (#P1 and #P2) mentioned that both know about EMD implementation to offenders in other countries, but they were not aware and did not have any knowledge that there are EMD wearers in their community. However, both agreed that the community members or leaders are willing to support the initiatives. This is supported by the following excerpt:

“These EMD implementations are good for the community where it helps to reduce crime rates in Malaysia. It also helps police to monitor the offenders time to time and track their movement through the system. I am aware that whenever I go, I want and need to be safe and secure. This implementation makes the community move forward in their lifestyle without fear” (Respondent P3).

Table 4 shows the result of authority agency where #PD1 and #PD2 refers to the two police parole officers from the PDRM who were interviewed. The score of this combination of respondents who involved directly in the EMD implementation shows the level of readiness is at Stage 8: Confirmation/Expansion of Community’s Readiness. It is referring to confirmation or expansion where most of the respondents have considerable knowledge of the implementation of EMD to offenders in Malaysia, including the level of program effectiveness. The authority agency leadership plays a key role in expanding and improving efforts. Most of the respondents in authority agencies strongly support the EMD implementation and understand its need. Participation level from this group is high. Obviously, the respondents have more than basic knowledge about the issue and have significant knowledge about local prevalence and local consequences. A considerable part of allocated resources is expected to provide continuous support. They are looking into additional support to implement new efforts. This is supported by the statement from respondent PD2:

“Training is really important to officers who are in charge of monitoring them. This is because the police need at least basic knowledge on how to use the electronic monitoring device. What stakeholders usually do is to send out a group of police for training to make sure they gain knowledge about EMD implementation”. (Respondent PD2)

Table 5 shows the overall community readiness score of the EMD implementation. According to the Community’s Readiness Model, a score of 6.6 is at Stage 6: Initiation. It refers to the initiation stage where most community members (the civilian, the employers, and the PDRM officers) have at least basic knowledge of local EMD implementation to offenders in Malaysia. Leadership plays a key role in planning, developing, implementing, modifying, and increasing the EMD implementation effort. The attitude in the community is, and some community members are involved in addressing the issue. For example, PDRM review alerts sent by the monitoring devices and investigate every alert to make sure the offenders are not breaching the violation. However, the community members have basic knowledge about the issue and only the employer of the wearer is aware that the issue occurs locally. It shows that the citizens gain knowledge about electronic monitoring through the media. They accessed the Internet to find any information through computers or smartphones but are not aware that there are EMD wearers in their community. It means that the EMD implementer must strengthen further efforts to address this issue.

Goal Development

Assessment of the community’s readiness stage has resulted at Stage 6: Initiation. This means that most community members have at least basic knowledge of the EMD implementation to offenders in Malaysia. However, from the findings, it reflected that most interviewees from the public or civilian group were not aware about the implementation of the EMD within their community. Only people who are related to the EMD implementation (the employer of the EMD wearer and police officers) have significant knowledge about EMD implementation to offenders done by the authority agency and are aware that the initiative occurs in Malaysia. It shows that the authority agency should play a key role in making sure the implementation is made known to the public in order for them to react accordingly and thus make the implementation run smoothly with community participation. Thus, they need to consider an awareness initiative to increase the awareness among the public on EMD implementation. The attitude in the community is positive towards this implementation and it shows when most of them agree by saying. One of the PDRM officers mentioned that. In addition to this statement, both officers of PDRM did mention

Authority leadership which refers to KDN and PDRM are actively supportive to secure the public with their electronic monitoring system. This was supported by the respondent feedback with their comment on the community's readiness towards EMD Implementation in Malaysia. Below points extracted from the respondent’s interview: -

“These EMD implementation is a good to our community where it can help to reduce crime rates in Malaysia. It also helps police to monitor the offenders time to time and track their movement through the system. I am aware that whenever I go, I feel safe and secure. This implementation makes community to move forward in their lifestyle without fear.” (Respondent P3).

Most of the respondents from the EMD project stakeholder group (the employer and PDRM) have considerable knowledge of their local efforts on electronic monitoring of offenders under their supervision and including the level of program effectiveness. They play a key role in expanding and improving efforts to keep the public safe. Most of the community strongly supports efforts or the needs for the efforts. It was agreed by all interviewees that crimes happen in their area and was successfully monitored using EMD. Civilians who are flexible, willing to learn and change, and capable enough for dealing with the changes were seen as critical for the smooth running of the EMD implementation. Most interviewees agreed that it requires sufficient knowledge among the offenders to place them in the right positions for EMD implementation. This means that there is a need to educate the offenders about electronic monitoring devices that they wear. Among transcript on this suggestion are as follows:

“Through EMD monitoring, it would be easy for me to monitor offenders under my supervision without close range. Maybe the offender does not have the full knowledge about the tag worn on their ankle, but sometimes they violated by breaching home detention or zone.” (Respondent PD2).

“Before we tag the device at the offender's ankle, I personally will remind the offender under my supervision about the do and don’ts of this procedure. Sometimes they violated by breaching the detention zone because they didn’t know about it.” (Respondent PD1).

Effective communication was emphasized by all interviewees as overly important throughout the entire new change after implementation. The interviewees considered that a continuous flow of clear information about the EMD implementation was necessary to keep everybody timely informed and ensure a clear understanding of electronic monitoring. In addition, a two-way communication flow process that fosters an environment of information sharing between the public and the PDRM was perceived as critical for more open and effective communication. It was suggested by the interviewees that this requires the public to be more aware in the discussions on change and supporting them to give their opinions and feedback on change.

The interviewees also mentioned that careful resource planning on developing or enhancing electronic supervision of offenders requires thoughtful consideration of a variety of issues. A systematic planning approach is the best way to achieve success of this initiative. Although planning is time consuming, and sometimes tedious, it is well worth the initial investment of time and effort. If a thorough planning process is not undertaken, agencies and professionals may pay a greater price in the future through unsuccessful program implementation and unproductive use of resources. As one interviewee explained:

“Having a lack of resources is my greatest fear towards readiness of EMD. But I have learned that planning resources is everything. We have two conditions here, first there are officers who have the essential technical skills but they are assigned to other tasks and second, there are sufficient officers with lack of essential technical skills who are willing to monitor the offenders who are wearing tags. Therefore, resource planning for the EMD implementation is absolutely critical...” (Respondent PD1).

In addition to this, most interviewees suggested that the provision of training for the EMD implementation was the key to EMD implementation success. The interviewees from PDRM considered appropriate training for their police officers as highly necessary and critical to ensure that the necessary knowledge for the implementation of the EMD in Malaysia. In PDRM, training was also perceived important to provide officers with the capacity for dealing with the system and offenders, but the stakeholder’s lack of resources did not allow all officers at the same time to have appropriate formal training. As the interviewee explained:

“Training is really important to officers who are in charge of monitoring them. This is because the police need at least basic knowledge on electronic monitoring devices on how to use it. What the Department usually does is send out the parole officers in charge to a training session to make sure they gain knowledge about EMD implementation” (Respondent PD2).

This was supported by another respondent who is the employer of the offender who is wearing the EMD as below:

“How well are our current EMD project implementations working and how can we make them better? As an employer of the offender who wear the electronic monitoring devices, I need to have a clear knowledge and guideline on the EMD procedure implemented by the Royal Malaysia Police.” (Respondent E1)

Conclusion

This study is done at the right time with its main objectives to investigate the current scenario of electronic monitoring device implementation in Malaysia and to identify the stage of community readiness towards electronic monitoring device to offenders in Malaysia. The concern of community safety and with assisting the offenders has resulted in an increased focus on the reintegration of offenders in the community and the reduction of crimes. EMD provides an instructive framework prior to implementation that allows for assessment of readiness and evaluation of alignment in community settings (Teeters et al., 2018).The application of EMD for offenders under preventative laws serves as a tool to assist the authority in controlling crimes. Thus, many countries are increasingly investing in the EMD for offenders, as an effort to both reduce the numbers of repeat offenders and as a cost-effective alternative to prison. Measuring the community’s readiness levels on several dimensions support the government efforts on EMD implementation. It helps to identify the community’s weaknesses and strengths, and the obstacles of the EMD implementation are likely to meet as this initiative moves forward. Apart from that, this study helps pointing to appropriate actions needed that match the community’s readiness levels.

Community Readiness Scenario and Status

EMD is part of the criminal justice agency tools used by parole and probation officers in Malaysia to manage offenders. The use of EMD on people under surveillance will reduce the cost of prisoners' imprisonment and foster a sense of prevention among detainees and potential criminals. In addition, the electronic monitoring device increases the ability of the parole and probation officers to be able to manage and control the activities of these offenders who are no longer in jail. Assessment of the community’s readiness stage has resulted at Stage 6: Initiation where some of the community members know about the local efforts and familiar with the purpose of the efforts. It also shows that the government are developing, improving, and implementing EMD initiatives. Moreover, the study also found two main findings that; most of the public or civilian is not aware of the existence of EMD initiatives: and insufficient knowledge and guidelines related to EMD initiatives among stakeholders namely parole officers, employers to EMD wearer and the local community.

The study recommends that educating the community about EMD initiatives is crucial to support offenders to return to community and be able to move on with their lives with the hope that the offenders do not fall back into committing the crimes. Some initiative needs to be given such attention which are: increase awareness and exposure of EMD initiatives through social media content: appropriate information of the EMD implementation on the implementing agencies website; collaboration between the implementing agencies, media practitioner and NGO to develop strategies; key leaders to promote the positive impact of EMD initiatives; and sufficient guidelines and training to upgrade knowledge and skills among the EMD implementation stakeholders.

Limitation and Future Research

This study involved six respondents; three civilians, two police officers and one offender’s employer, and it could not represent the accurate population of the community. Furthermore, it is hard to find respondents among the offender’s employers, and it took a long time to get their commitment for this study. Sometimes, the parole officer who has all the personal details of the offenders did not want to reveal the information due to its confidentiality status. This study is missing the EMD wearer offenders’ view. As mentioned earlier, the researchers were not able to get input from one of the main stakeholders because there was no offender volunteering to be in this study. It is strongly recommended to include the offenders for future research as it would provide richer picture related to the EMD implementation. This study only provides insights with a limited and narrow view on the studied phenomena because this research was small-scale that focused on EMD implementation. Further study is therefore recommended with a large-scale or wider sample of different key person in EMD implementation including the civilians.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the reviewers for all their careful, constructive, and insightful comments in making our manuscript clearer and more useful to the reader. We also wish to extend our gratitude and thank you to the PDRM officers and the civilians who voluntarily took part in this study.

References

Belur, J., Thornton, A., Tompson, L., Manning, M., Sidebottom, A., & Bowers, K. (2020). A Systematic Review of the Effectiveness of the Electronic Monitoring of Offenders. Journal of Criminal Justice, 68.

Crump, C., Weisburd, K., & Koningisor, C. (2017), Electronic monitoring isn’t kid friendly. The Sacramento Bee. https://sites.law.berkeley.edu/inthenews/2017/07/20/electronic-monitoring-isnt-kid-friendly/

de Oliveira Corrêa, A., Brown, E. C., Lee, T. K., Mejía-Trujillo, J., Peréz-Gómez, A., & Eisenberg, N. (2020). Assessing Community Readiness for Preventing Youth Substance Use in Colombia: A Latent Profile Analysis. International journal of mental health and addiction, 18(2), 368–381.

Fitzalan Howard, F. (2020). The Experience of Electronic Monitoring and the Implications for Effective Use. The Howard Journal of Crime and Justice, 59(1), 17–43.

Gansefort, D., Brand, T., Princk, C., & Zeeb, H. (2018). Community Readiness for the Promotion of Physical Activity in Older Adults—A Cross-Sectional Comparison of Rural and Urban Communities. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 15(3).

Garland, D. (2002). The Culture of Control. Crime and Social Order in Contemporary Society. Oxford University Press.

Hucklesby, A., & Holdsworth, E. (2020). Electronic Monitoring in Probation Practice. HM Inspectorate of Probation. https://www.justiceinspectorates.gov.uk/hmiprobation/wp-content/uploads/sites /5/2020/12/Academic-Insights-Hucklesby-and-Holdsworth-FINAL-1.pdf

Hwang, Y. I. J., Simpson, P. L., & Butler. T. G. (2021). Participant Experiences of a Post-Release Electronic Monitoring Program for Domestic Violence in New South Wales, Australia. Journal of Criminology, 54(4), 482-500.

Kucharson, M. K. (2006). GPS Monitoring: A Viable Alternative to the Incarceration of Nonviolent Criminals in the State of Ohio. Cleveland. State Law Review, 54(4), 637.

Liu, M., Zhang, X., Xiao, J., Ge, F., Tang, S., & Belza, B. (2018). Community Readiness Assessment for Disseminating Evidence-Based Physical Activity Programs to Older Adults in Changsha, China: A Case for Enhance®Fitness. Global Health Promotion, 27(1), 59-67.

Meuer, K., & Woessner, G. (2018). Does Electronic Monitoring as a Means of Release Preparation Reduce Subsequent Recidivism? A Randomized Controlled Trial from Germany. European Journal of Criminology, 17(5), 563-584.

Ministry of Home Affairs (2021). Statistik Pemakaian Electronic Monitoring Device (EMD) [Electronic Monitoring Device (EMD) Usage Statistics.]. https://www.data.gov.my/data/ms_MY /organization/ministry-of-home-affairs

Nwagu, E. N., Dibia, S. I. C., & Odo, A. N. (2020). Community Readiness for Drug Abuse Prevention in Two Rural Communities in Enugu State, Nigeria. SAGE Open Nursing, 6, 1-10.

Prevention of Crime Act 1959. (2015). Retrieved on September 1, 2015, from https://www.ilo.org/dyn/natlex/docs/ELECTRONIC/98959/117922/F-510604969/MYS98959%202015.pdf

Teeters, L. A., Heerman, W. J., Schlundt, D., Harris, D., & Barkin, S. L. (2018). Community Readiness Assessment for Obesity Research: Pilot Implementation of the Healthier Families Programme. Health Res Policy Sys 16(2).

Tri-Ethnic Center Community Readiness Handbook 2nd edition. (2014). https://tec.colostate.edu/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/CR_Handbook_8-3-15.pdf

Utusan Malaysia (2021). Projek Perintis Peranti Elektronik Pantau Kuarantin [Electronic Device Pilot Project for Quarantine Monitoring] (Utusan Malaysia 13 August 2021). Retrieved on October 3, 2021, from https://www.utusan.com.my/Berita/2021/08/Projek-Perintis-Peranti-Elektronik-Pantau-Kuarantin/

Xavier, P., Rita, M., Felizardo, A. P. F., & Alves, F. W. A. (2021). Smart Prisoners: Uses of Electronic Monitoring in Brazilian Prisons during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Surveillance & Society 19(2), 216-227. https://ojs.library.queensu.ca/index.php/surveillance-and-society/index

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

31 October 2022

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-958-0

Publisher

European Publisher

Volume

3

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-802

Subjects

Multidisciplinary sciences, sustainable development goals (SDG), urbanisation

Cite this article as:

Ahmad Nawi, H. S., Abu Hassan, R., Kunalan, N., Omar, S. F., Ahmad Shukor, N. S., & Osman, S. (2022). Assessing Community Readiness For Electronic Monitoring Device Towards Community Well-Being. In H. H. Kamaruddin, T. D. N. M. Kamaruddin, T. D. N. S. Yaacob, M. A. M. Kamal, & K. F. Ne'matullah (Eds.), Reimagining Resilient Sustainability: An Integrated Effort in Research, Practices & Education, vol 3. European Proceedings of Multidisciplinary Sciences (pp. 677-691). European Publisher. https://doi.org/10.15405/epms.2022.10.64