Abstract

Social and emotional learning (SEL) is promoted by offering teachers’ SEL workshops worldwide. However, little is known about their short-term and long-term outcomes. We explored how teachers benefit from Lions Quest (Mitt Valg in Norwegian) training in the short and long term in Norway. The development of teachers was investigated by exploring their perceived importance and sense of competence in teaching SEL during an almost two-year period. The development of their students’ SEL was explored as well. Imputed values from the intervention group (n = 247) and the comparison group (n = 47) were used in analysing teachers’ short and long-term outcomes. Students’ intervention group consisted of 112 students and the comparison group consisted of 53 students. Data were collected from the teachers three times and from the students two times via Likert-scale questionnaires. The results indicated that the teachers felt to be more competent in teaching SEL after their Lions Quest (Mitt Valg) teacher training. This trend appeared to be continuing in the long run. Students’ SEL among the intervention group slightly increased whereas SEL among the comparison group decreased during their teachers' training. Lions Quest (Mitt Valg) intervention appeared to improve teachers’ sense of competence to teach SEL at school. In addition, findings showed that teachers were willing to implement LQ as part of their teaching.

Keywords: Social and emotional learning (SEL), Lions Quest (LQ), intervention, teacher training

Introduction

During the last decade social and emotional learning (SEL) has become an increasingly important part of education in many countries. Today the importance of developing social and emotional skills of schooling is recognized worldwide even though their promotion and implementation strategies vary from country to country (OECD, 2015). The recent promotion of SEL can be explained in many ways. The rise of the positive psychology movement has challenged educators to recognize the ways and procedures to facilitate students’ wellbeing (Seligman & Csikszentmihalyi, 2014; Taylor et al., 2017). In addition, Durlak et al. (2011) and Taylor et al. (2017) could clearly prove in their reviews that systematic SEL studies also improve students’ performance in academic subjects., The 21st century skills currently include social and emotional competence as an essential in active citizenship (European parliament, 2015; Lonka et al., 2018; OECD, 2018; Trilling & Fadel, 2009). Accordingly, little wonder why SEL can now be considered as, like Professor Humphrey (2015) stated, “a dominant orthodoxy in education”.

This study focuses on exploring the change in Norwegian teachers’ readiness to teach social and emotional learning (SEL) when they participate in Lions Quest teacher workshops. In addition, the development of their students’ SEL during Lions Quest (LQ) in Norway will be studied. The present study continues the series of investigations for the development of teachers’ SEL through LQ program studies in different countries (usually lasting 2-3 consecutive days) that point out that the goals of the workshops were reached in quite harmonious ways regardless of the culture (Talvio et al., 2016; Talvio et al., 2022; Talvio et al., 2019). In Norway, the program is called “Mitt Valg”. There is hardly any previous research regarding the Norwegian version, which is a bit different than the workshops in many other countries. What is special about Mitt Valg program from other LQ versions is that it is split in two parts that maintain the learning process even for the whole school year, including exercises between the two face-to-face workshops. Unlike in many other countries in Norway every school participating in the LQ, must sign an agreement of commitment for three years. The LQ teachers are also offered access to the online community of practice where they can share their experiences and ask questions from the experts or other LQ teachers. In previous international comparisons regarding LQ we focused on teachers’ readiness to teach SEL. The present study looks at more closely, how the special process-oriented arrangement in Norway works with both teachers and their students.

In some previous studies in Norway, upper secondary school students were offered intervention which was targeted on creating environments where students’ mental health is promoted and where they were encouraged to participate, feel confident and experience the sense of belonging (Larsen et al., 2021), which all are important outcomes of SEL (Elias et al., 1997). Even though their preliminary results indicated positive development among young peoples, the students’ sense of loneliness and mental health problems did not decrease or just remained on the same level, but instead, even increased. It is interesting to see whether LQ, i.e., Mitt Valg may work better in the Norwegian context.

What is social and emotional learning (SEL)?

Social and emotional learning (SEL), first introduced in 1994, is a conceptual framework including core components, namely self-awareness, self-management, social awareness, relationship skills and responsible decision making (Elias et al., 1997). These skills enable individuals to identify their strengths and limitations and to develop positive feelings about themselves and others. The benefits of SEL can be approached from the perspective of intrapersonal and interpersonal competencies which Gardner (1993) defined as essential for oneself and with others for understanding social interaction (Rita, 2000). The improvement of learners’ intrapersonal competence takes place when their self-awareness or self-management is developed. When learners are aware of their inner reality, i.e., emotions, needs and wants, they can regulate themselves in various situations and help themselves to fulfil their needs and manage to reach goals. Interpersonal competence gives insight to learners’ social awareness and their relationship skills which are helpful in making meaningful relationships and enhancing effective interaction. According to the SEL concept, the third competence is cognitive competence. It advances capabilities to collaborate effectively and promote responsible decision making and ethical choices with others possible (https://casel.org/core-competencies/).

How is SEL studied?

Research on SEL has been available already from the time when the theory of SEL was created in 1990’s (Elias et al., 1997). At that time, it was typical that the studies targeted students' SEL as a result of an intervention in the classroom. Talvio et al. (2015) pointed out that the typical problem was that the intervention was seldom well described. It followed that it is difficult to know what content and methods were used and whether they were effective or not when teaching SEL for students. Later, the essence of teachers’ development in their competence and their overall readiness to implement SEL in the classroom were better understood and it resulted to more emphasis on research on both teachers’ and their students’ development of SEL including more detailed descriptions of the intervention and overall, the learning process both of students and their teachers.

As mentioned before, indirect benefits of SEL for students include an improvement of academic performance and wellbeing. The direct benefits contain improved competence in SEL, that is, better attitudes and behaviours toward self, others and school. SEL also fosters prosocial behaviour reducing conduct and internalizing problems (Taylor et al., 2017). Similar results had been found also by many other research groups, too (i.e., Brock et al., 2008; Durlak et al., 2011; Jiménez Morales & López Zafra, 2013; Zins & Elias, 2006; Zins et al., 2007).

Teachers’ SEL

Fostering SEL in the political and administrative level should also include the promotion of teachers’ readiness to teach SEL because they are key people in implementing SEL in the classroom. Research indicates that teachers must know the content they teach (Ferreira et al., 2021). And of course, teachers must have developed a pedagogical understanding of how to deliver the content they teach. Additionally, as far as SEL is concerned, teachers need to be competent in applying the skills they teach in daily interactions with their students because teachers are always their students’ role-models both in good and in bad (Bandura, 2006).

Today we know that teachers can learn social and emotional skills. Thus, SEL is not a trait that people are born with, but they are skills that anyone can develop even at adult age (Talvio, 2014; OECD, 2015). Yet, our previous study (Talvio et al., 2022) indicated that the ability to apply knowledge can be declined in the long term if SEL skills are not systematically maintained in practice.

Of course, dosage, in other words, how often teachers teach SEL in the classroom has a linear effect on the success in students SEL (Durlak, 2016; Matischek-Jauk et al., 2018). Therefore, we also looked at how often the Norwegian teachers apply what they have learned during LQ training (i.e., Mitt Valg). The frequency talks about their behavioral engagement in teaching SEL.

Sometimes the frequency of implementing SEL depends on prioritizing the choices which are determined by the teacher's perceived importance about the task. Expectancy value theory (Eccles & Wigfield, 2002; Wigfield & Eccles, 2000) clarifies which components have a role in teachers’ choices. Teachers’ readiness to implement SEL in their teaching is strongly related to their engagement of SEL (intrinsic value), their perceived importance of SEL (attainment value), their willingness to invest their resources in teaching SEL (cost) and their perceived usefulness of SEL (utility value). In addition, according to the self-determination theory (Deci & Ryan, 2002) teachers choose to teach what they think they are good at because it promotes their wellbeing. Accordingly, the sense of their competence in teaching SEL plays an important role, too. It follows that the training for teachers on SEL should include elements that promote their task values and their sense of competence in teaching SEL.

In the present study, we are only looking at the attainment value and the sense of competence. We also looked at how often the Norwegian teachers apply what they have learned in the Mitt Valg workshop.

Are the outcomes of SEL related to the age of the students?

Not all interventions to promote students’ SEL have been successful. In Norway, Larsen et al. (2021) concluded that a holistic intervention for improving psychosocial environment was not helpful in preventing students’ loneliness or mental health problems among teenagers. Regarding SEL skills, Corcoran, Cheung et al. (2018) stated that even the most popular SEL approaches used at school do not always present strong evidence of effectiveness in learning SEL. For example, our own international study in five EU countries showed that after the SEL intervention the favourable outcomes took place only among 8-11 years old students but nor among teenagers (Berg et al., 2021). It is also possible that students’ SEL develops only partially. In our previous study, even 8-11 old students developed only in their intrapersonal competence, namely, self-awareness and self-management (Berg et al., 2021).

Interestingly, both above-mentioned results (Corcocan et al., 2018; Larsen et al., 2021) were collected among teenagers. It has been argued that to be able to benefit from SEL, students should be in the right developmental stage. Indeed, some studies suggest that there are some typical SEL programs that work very well with children, but have a poor track record with middle adolescents (Yeager, 2017).

Fidelity of the program

There may be a variation in the emphasis of SEL components of the intervention (Lonka & Talvio, 2022), or the standards of the school do not address SEL comprehensively but only partly (Schonert-Reichl et al., 2015). Accordingly, Durlak et al. (2016) suggest that fidelity of the program is important in an effective implementation. On the other hand, the natural procedure of SEL might have a role too. Instead of a straight linear model SEL can be understood as a deepening spiral pathway to thrive. The change starts always from oneself, i.e., intrapersonal competence and after that it is time for the development of interpersonal competence. Vygotsky’s internalization/externalization process (1978) comes close to this idea: first internalizing the concept in social interaction and then externalizing it in new interactions with others (Lonka & Talvio, 2022). Hence, it is natural that the learning results indicate SEL to be learned sometimes only partly because SEL happens in phases.

To conclude, schools alone can’t guarantee students’ success in SEL. However, administrators can promote SEL in multiple ways at school. SEL is already a part of national core curricula worldwide so having a systematic plan for SEL in individual schools is beneficial for promoting its implementation. Sometimes the organiser of the SEL program requires schools to sign an agreement about implementation strategy to make sure the programme will be delivered as it was meant to be. Teachers are expected to follow the LQ curriculum and conduct SEL classes as planned during this time and the whole school promotes teachers to implement LQ in their classrooms. Since the Norwegian is not quite similar to the programs we previously investigated, it is especially interesting to look at how their specific version reaches similar outcomes to our global evaluations of LQ (Talvio et al., 2016; Talvio et al., 2022; Talvio et al., 2019).

Purpose of the Study

The results of our previous studies of LQ indicated positive changes in the short term (during the LQ teacher workshop) in teachers’ perceived importance of SEL and their sense of competence in implementing it (Talvio et al., 2016; Talvio et al., 2019). The purpose of this study was to investigate the possible benefits of LQ to teachers both in the short and in the long term. In addition, this study will also investigate the possible benefits of the teacher LQ training to their pre-puberty students.

Research Questions

To investigate the phenomenon described above the following research questions were addressed:

Does Norwegian version of LQ change teachers’ perceived importance of SEL?

Does Norwegian version of LQ change teachers’ sense of competence in implementing SEL?

Do students whose teachers participate in the Norwegian version of LQ benefit from this training?

Methodology

Context

Education is mandatory for all children aged 6–16 year in Norway and it is paid by the government. Primary school lasts for seven years. General teacher education consists of a four-year vocational training course of 240 credits. The course comprises a compulsory component of 120 credits including educational theory and an elective component of 120 credits consisting of at least 60 credits in subjects that are taught in the primary and lower secondary school. The subject studies shall include subject didactics and normally practical training as well (https://www.european-agency.org/sites/default/files/Teacher-Training-in-Norway.pdf).

Intervention

Lions Quest (LQ) used as an intervention for teachers and their students is a very international SEL program. It has been implemented in 105 countries and translated into over 45 languages (Talvio et al., 2022). The duration of the LQ teacher training workshop in Norway is 1.5-days including a refresher workshop after 3-6 months (Kiefer et al., 2021). The idea is that the teachers gather for a full day to learn basic knowledge on SEL and to adopt skills for conducting LQ in the classroom. The teachers are provided with a comprehensive LQ material package and an access to the online community of LQ teachers. After the first workshop day the teachers implement LQ in the classroom testing and collecting experiences of the implementation process. In the refresher workshop the teachers deepen their understanding about the LQ by sharing their experiences, ideas, and concerns (see https://www.determittvalg.no/skole/bestill-kurs-skole.)

Participants

Teachers from 16 of lower secondary schools in Norway participated in this study. The intervention group ( = 247) consisted of teachers who participated in the LQ programme. The data from the comparison group ( = 47) who did not participate in the LQ were collected approximately at the same time as the data from the teachers who attended the training. Altogether, 67 % of the teacher participants were female and 12 % male and 21% preferred not to say. On average, they had 14 years of work experience ( = 9.5). Students’ intervention group ( = 112) consisted of students whose teachers participated in the LQ. Altogether, 53 students whose teachers did not attend the LQ comprised the comparison group. Data were collected two times before and after their teachers’ LQ training.

Questionnaire/Materials

We investigated how frequently the teachers implemented LQ-methods in their classroom after the training by asking “How often have you used the Mitt Valg -methods so far with your students?”. Response options ranged from “daily” (6) to “never” (1).

The LQ questionnaire for teachers consisted of two components, namely, how teachers in promoting the LQ goals. The development of the LQ questionnaire for teachers is described elsewhere and the reliabilities were good. (Talvio et al., 2016). The participants evaluated 14 statements developed using a seven-point Likert scale, with response options ranging from “totally disagree” (1) to “totally agree” (7) or “not at all important” (1) to “very important” (7).

This scale consisted of 7 statements that were answered at a seven-point Likert scale, with response options ranging from “not at all important” (1) to “very important” (7). Examples of statements used to measure participants’ perceptions of the importance of LQ included for instance: “It is primarily the teacher's duty to create a classroom environment where all students feel valued”, “It is the teacher’s duty to teach interactive skills such as listening and conversation skills” and “It is the teacher’s duty to teach emotional skills such as self-control”. The value of Cronbach’s Alpha for this scale was α = .86.

This scale consisted of 7 statements that were answered at a seven-point Likert scale, with response options ranging from “totally disagree” (1) to “totally agree”. We investigated teachers’ opinions of their competence in promoting the LQ goals by using statements such as “I am very skilled at teaching interactive skills, such as listening and conversation skills” and “I am very skilled at teaching emotional skills, such as self-control”. The value of Cronbach’s Alpha for this scale was α = .85.

was measured by Social Emotional Competence Questionnaire (SECQ) (Zhou & Ee, 2012), which has been designed to evaluate how competent children (from grades 4 to 12) are in five elements of SEL (see Elias et al., 1997). The five elements of the SECQ are the same as the components of SEL, in other words, self-awareness, self-management, social awareness, relationship skills, and responsible decision-making. Sample item of is “I know when I am moody”. A statement “If someone is sad, angry or happy, I believe I know what they are thinking” is a sample of. “I can control the way I feel when something bad happens'' is a statement sample of. Sample item ofis “I always try to comfort my friends when they are sad”. Finally, the sample statement of responsible is: “When making decisions, I take into account the consequences of my actions''. Students rated these items using a 6-point Likert scale with response options ranging from “completely disagree” to “completely agree”. The value of Cronbach’s Alpha for this scale was α = .93.

Data collection

The questionnaires used to collect the data in both pre- and post-tests were on an electronic platform called SurveyGizmo. A back translation method was used to make sure that the Norwegian translation of the questionnaire would be appropriate.

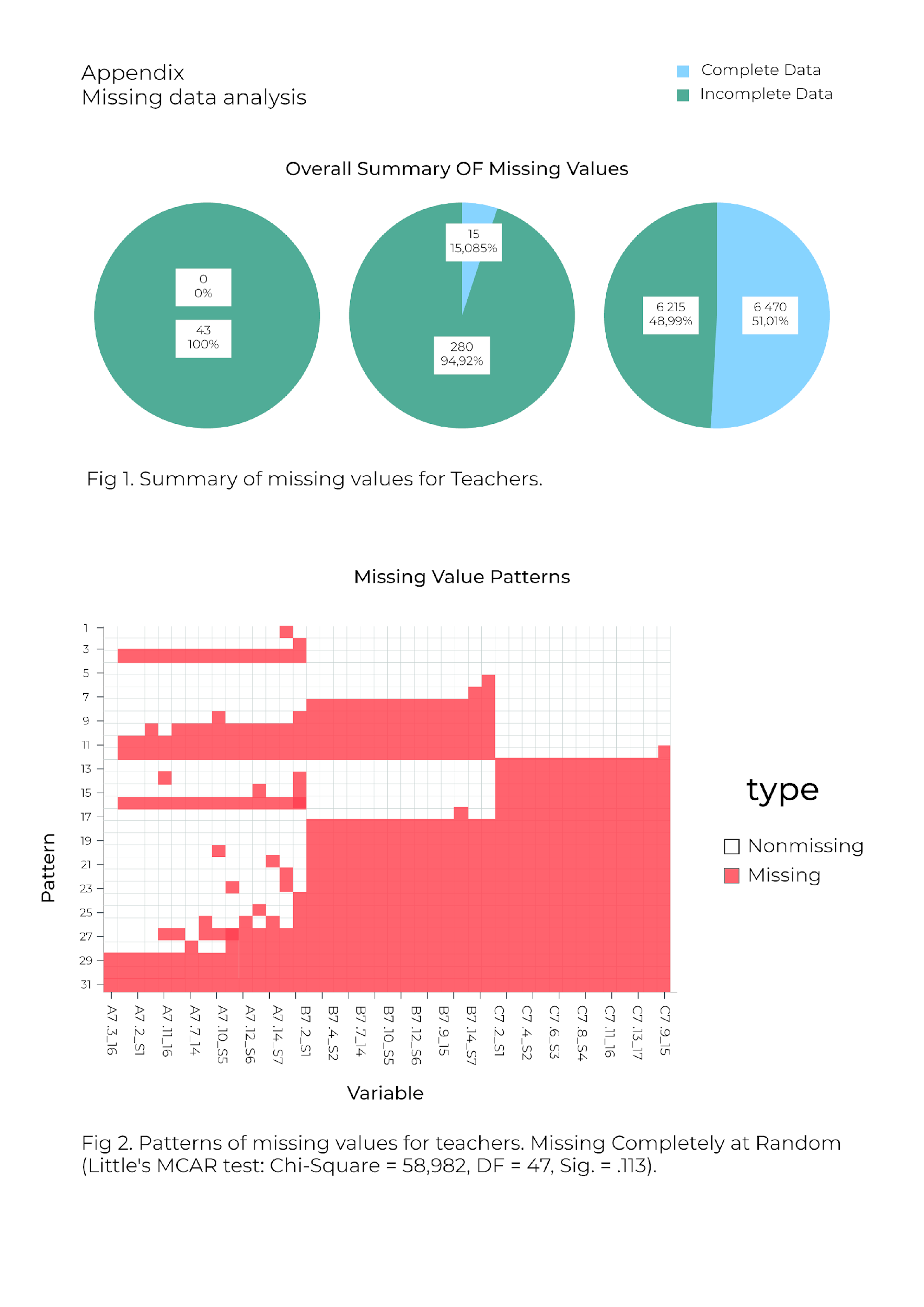

Teachers’ data were collected three times for analysing the short-term and long-term outcomes of the LQ teacher workshop. For robustness checks, given the amount of missing data (see Figure 4), the analyses were repeated with data imputed with Expectation Maximization -algorithm. The training lasted almost two years, starting in the spring of 2020 (T1) before the first day of the teacher LQ. The second measuring point (T2) was right after the first day of teacher LQ and in the fall of 2021 when the training was totally completed the data was collected for the third time (T3). Students’ data were collected twice: before the teachers’ LQ (T1) and after their teachers’ training was totally completed (T2).

Analyses

Data from both teachers and their students were analysed in a similar way. First the mean sum scores in each measuring point were calculated and then they were used as variables in further analysis. The sum variables for teachers were and and for students. Repeated measures ANOVA (see e.g., Runhaar et al., 2013) was used to examine the effect of the intervention with regards to statistically significant change over time across groups in the variables by estimating the “time*group interaction. The analyses were conducted with IBM SPSS 27 and Jamovi 2.2.2.0.

Ethical considerations

The participants were informed about measures taken to protect their privacy and they were assured of their information and responses remaining anonymous. They were also informed about their right to withdraw their responses from this study at any time without warning in advance or explanation. None of the participants asked for their answers to be removed from the data. Students’ parents were asked for written permission to let their children participate in this study.

Findings and Discussion

Teachers

We investigated how the teachers (n= 211) implemented LQ-methods in their classroom after the training. Altogether 6 % of the teachers used LQ-methods daily, 20 % many times a week, 25 % once a week, 25% once a month, 18 % less than once a month and 6 % never.

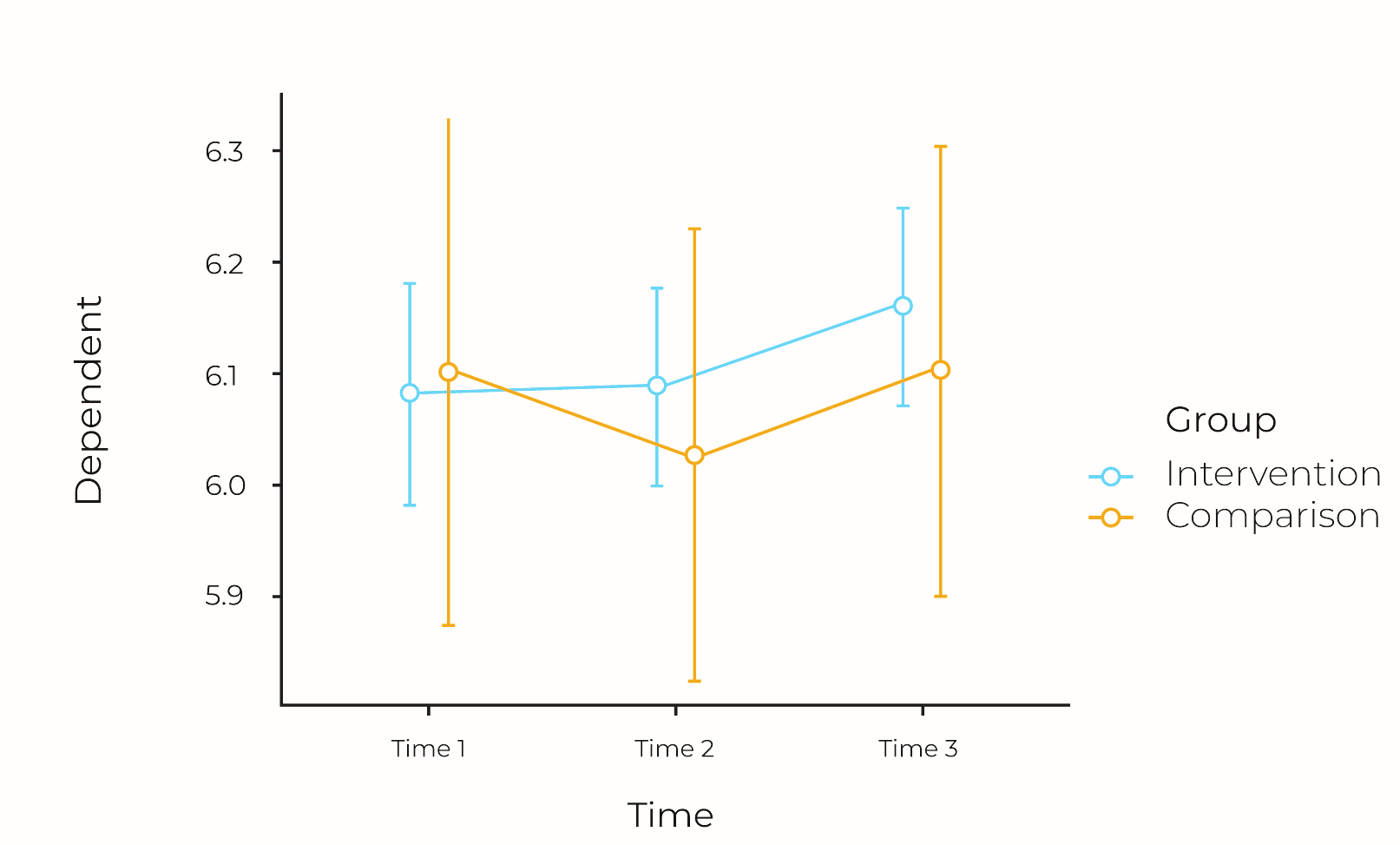

Regarding the three measuring points (T1, T2, T3) the intervention group improved in from T1 towards T3. The comparison group started from higher, but they collapsed around T2 and did not recover on T3. Figure 1 shows that the time*group interaction was not significant between measuring points T1, T2 and T3 (F = 1.57, p = .21).

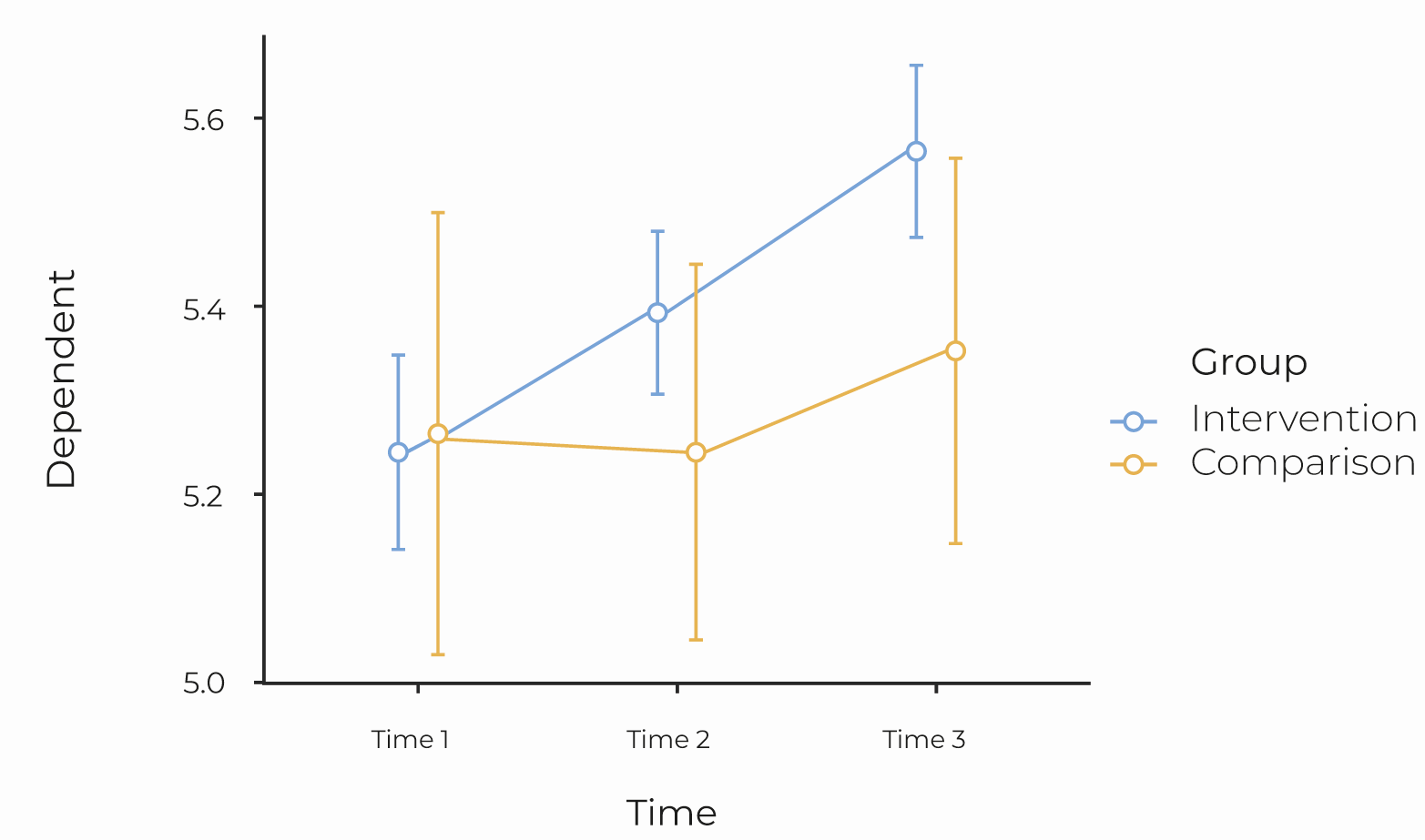

Regarding the sense of competence both the intervention group and the comparison group started from the same level (T1). However, the intervention group scored higher in both T2 and T3 whereas the comparison group remained on the level on T2 and then slightly improved on T3. The time*group interaction between the intervention and the comparison group in the sense of competence in measuring points T1, T2 and T3 was statistically significantly different (F = 9.52, p < .001, η²g = .002) showing that the intervention group scored significantly higher on the measuring points T2 and T3 than the comparison group (Figure 2).

Students

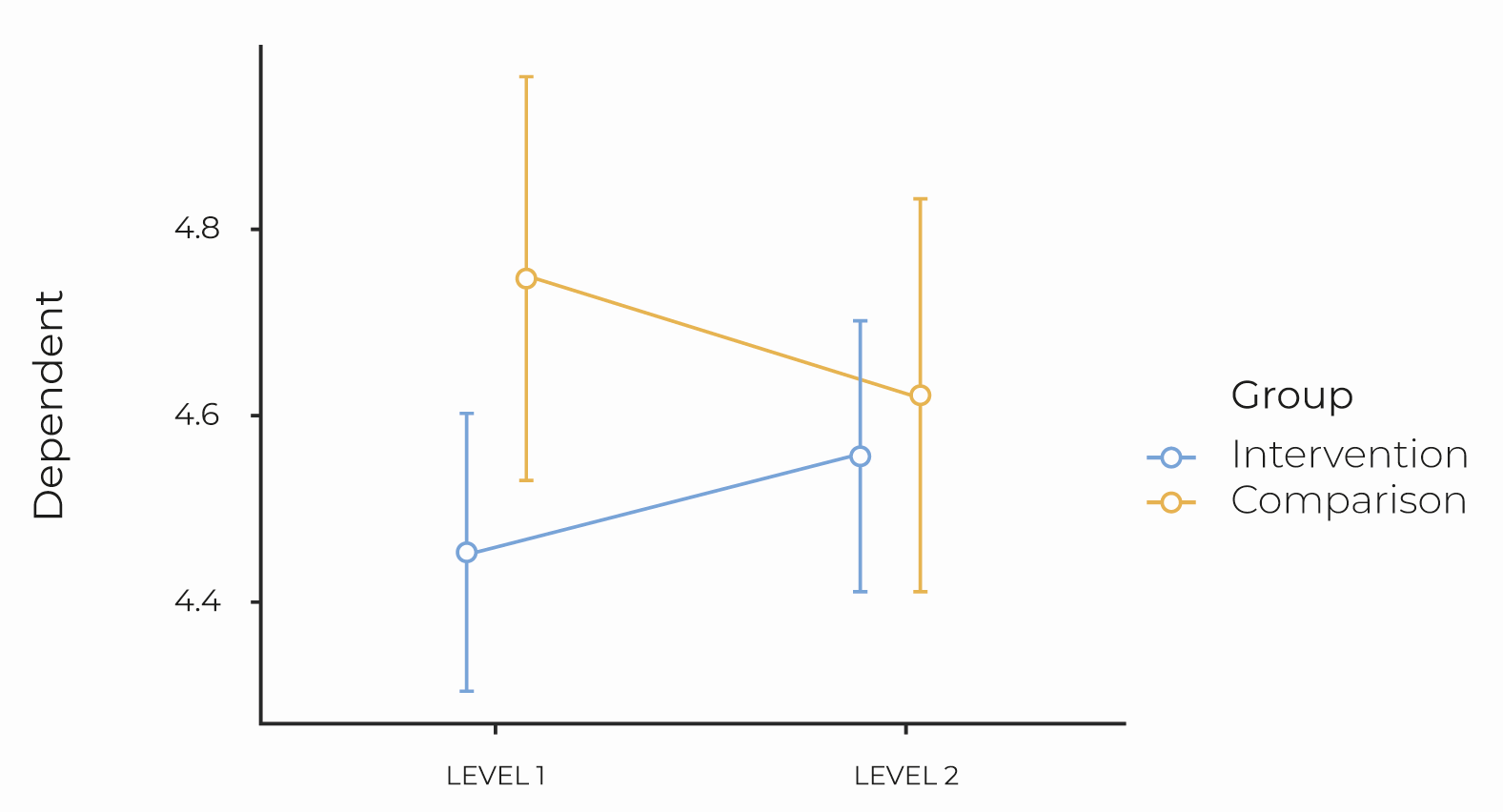

Repeated measures ANOVA indicated that among the intervention group students’ SEL slightly improved during the intervention. Among the comparison group the development was negative. Figure 3 shows the statistically significant interaction of these two groups. ( = 6.73, = 0.01, = 0.005).

The results of the present study indicated that the teachers’ sense of competence increased in teaching SEL and promoting a positive learning environment after their Lions Quest (Mitt Valg) teacher training. This result did not drop in the long run. Students’ SEL among the intervention group slightly increased whereas SEL among the comparison group decreased during their teachers' training. However, since the intervention group started from the lower level than the comparison group in the first measuring point and after their teachers’ training the intervention group reached only the same level as the comparison group it is difficult to draw strong conclusions of the benefits from LQ to the students.

Methodological reflections

The reader should bear in mind that the teachers' questionnaire was a self-report, and it does not necessarily reflect what happens in real life at school. It is possible that the teachers feel competent in teaching SEL after the LQ but when they are supposed to put it into practice in the classroom, they end up giving in. However, in this study we could see that the students whose teachers participated in the LQ developed their skills of SEL at least to some extent. Thus, it is likely that the teachers had succeeded in implementing SEL in their classrooms and they have done it in the way that teaching SEL has been beneficial to their students.

The missing data of teachers’ samples, especially on the third measuring point, were causing some challenges. Even though the data were imputed with Expectation Maximization -algorithm it is important to bear in mind that the interpretation of the development especially between T2 and T3 is guarded. On the other hand, the results of this study are aligned with our previous studies (Talvio et al., 2016; Talvio et al., 2022; Talvio et al., 2019). Accordingly, it might be appropriate to say that LQ was helpful for teachers and the trend in their development appeared to continue. However, more studies are needed to confirm long-term results.

The measuring instruments for teachers worked in the Norwegian context in the similar way as in our previous global measurements indicating good concurrent validity. Regarding students’ development of SEL it might be a good idea to observe students’ behavioural change after their SEL studies instead of using a questionnaire because then it would be possible to analyse how the students apply the studied skills of SEL in real situations. For the developmental purposes of the LQ, it would also have been interesting to see what elements of SEL (i.e., self-awareness, self-management, social awareness, relationship skills, responsible decision making) developed during their teachers’ LQ but unfortunately in the Norwegian context the measuring instrument we used worked well only as a one SEL sum variable.

Conclusions

It can be concluded that the Norwegian version of Lions Quest (Mitt Valg) intervention appeared to improve teachers’ sense of competence to teach SEL at school. In addition, findings showed that after the intervention, most teachers were willing to implement LQ as part of their teaching at least once a week. This study showed that Mitt Valg helped Norwegian teachers to feel competent in teaching SEL. The results of this study are aligned with our previous studies of LQ teacher workshops in different countries (Talvio et al., 2016; Talvio et al., 2022; Talvio et al., 2019) strengthening the conclusion that international LQ concept can be implemented in various cultures and contexts fostering teachers’ readiness to teach social and emotional learning in their classrooms.

The importance for social and emotional learning has finally been acknowledged in comprehensive education. Therefore, there is a strong need to organise continuous teacher training now because only recently SEL has been included in teacher education in many countries.

This study was conducted when the Covid-19 started. Many teachers suddenly had to start working in a different way and create methods for online teaching. In Norwegian LQ a lot of online material was already available and even the LQ teachers' community had already been created. It would be interesting to explore how the pandemic speeded up the implementation of the new tools provided by Mitt Valg and how they will be used in the future.

Acknowledgments

This study was partially funded by the Lions Clubs International Foundation. The last author was funded by Finnish Strategic Research Council (#327242, #352545).

References

Bandura, A. (2006). Toward a psychology of human agency. Perspectives on psychological science, 1(2), 164-180. DOI:

Berg, M., Talvio, M., Hietajärvi, L., Benítez, I., Cavioni, V., Conte, E., Cuadrado, F., Ferreira, M., Košir, M., Martinsone, B., Ornaghi, V., Raudiene, I., Šukyte, D., Talić, S., & Lonka, K. (2021). The Development of Teachers' and Their Students' Social and Emotional Learning During the “Learning to Be Project”-Training Course in Five European Countries. Frontiers in Psychology, 12. DOI:

Brock, L. L., Nishida, T. K., Chiong, C., Grimm, K. J., & Rimm-Kaufman, S. E. (2008). Children’s Perceptions of the Classroom Environment and Social and Academic Performance: A Longitudinal Analysis of the Contribution of the Responsive Classroom Approach. Journal of School Psychology, 46, 129-149. DOI:

Corcoran, R. P., Cheung, A. C., Kim, E., & Xie, C. (2018). Effective universal school-based social and emotional learning programs for improving academic achievement: A systematic review and meta-analysis of 50 years of research. Educational Research Review, 25, 56-72. DOI:

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2002). Overview of self-determination theory: an organismic dialectical perspective. In E. L. Deci, & R. M. Ryan (Eds.), Handbook of self-determination research. University of Rochester Press.

Durlak, J. A. (2016). Programme implementation in social and emotional learning: basic issues and research findings. Cambridge Journal of Education, (46)3, 333-345. DOI:

Durlak, J. A., Weissberg, R. P., Dymnicki, A. B., Taylor, R. D., & Schellinger, K. B. (2011). The Impact of Enhancing Students’ Social and Emotional Learning: A Meta-Analysis of School-Based Universal Interventions. Child Development, 82, 405-432. DOI:

Eccles, J. S., & Wigfield, A. (2002). Motivational Beliefs, Values, and Goals. Annual Review of Psychology, 53, 109-132. DOI:

Elias, M. J., Zins, J. E., Weissberg, R. P., Frey, K. S., Greenberg, M. T., Haynes, N. M., Kessler, R., Schwab-Stone, M. E., & Shriver, T. P. (1997). Promoting social and emotional learning: Guidelines for educators. Alexandria, V.A.: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development,

European Parliament. (2015). Innovative schools: Teaching & learning in the digital era – workshop documentation. Brussels: European Parliament. www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/STUD/ 2015/563389/IPOL_STU%282015%29563389_EN.pdf

Ferreira, M. (2021). Teachers' well-being, social and emotional competences, and reflective teaching–a teacher's continuous training model for professional development and well-being. In M. Talvio, & K. Lonka (Eds.), International Approaches to Promoting Social and Emotional Learning in Schools: A Framework for Developing Teaching Strategy (pp. 207-219). Routledge, Taylor & Francis. DOI:

Gardner, H. (1993). Multiple intelligences: The theory in practice. Basic Books.

Humphrey, N. (2013). Social and emotional learning. A critical appraisal. SAGE publications Limited. DOI:

Jiménez Morales, I., & López Zafra, E. (2013). Impact of Perceived Emotional Intelligence, Social Attitudes and Teacher Expectations on Academic Performance. Electronic Journal of Research in Educational Psychology, 11, 75-98. DOI:

Kiefer, M., Haynes, K., Kasper, K., & Dickson, A. (2021). Practitioner adaptations of a social and emotional learning curriculum in international contexts. In M. Talvio, & K. Lonka (Eds.), International Approaches to Promoting Social and Emotional Learning in Schools: A Framework for Developing Teaching Strategy (pp. 207-219). Routledge, Taylor & Francis. DOI:

Matischek-Jauk, M., Krammer, G., & Reicher, H. (2018). The life-skills program Lions Quest in Austrian schools: implementation and outcomes. Health Promotion International, 33(6), 1022–1032. DOI:

Larsen, T. B., Urke, H., Tobro, M., Årdal, E., Waldahl, R. H., Djupedal, I., & Holsen, I. (2021). Promoting mental health and preventing loneliness in upper secondary school in Norway: effects of a randomized controlled trial. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 65(2), 181-194. DOI:

Lonka, K., Makkonen, J., Berg, M., Talvio, M., Maksniemi, E., Kruskopf, M., Lammassaari, H., Hietajärvi, L., & Westling, S. K. (2018). Phenomenal Learning from Finland. Edita.

Lonka, K., & Talvio, M. (2022). Epilogue: Towards an integrative view of social and emotional learning. In M. Talvio, & K. Lonka (Eds.), International Approaches to Promoting Social and Emotional Learning in Schools: A Framework for Developing Teaching Strategy (pp. 220-233). Routledge, Taylor & Francis. DOI:

OECD. (2015). Skills for Social Progress: The Power of Social and Emotional Skills, OECD Skills Studies, OECD Publishing. DOI:

OECD. (2018). Education at a Glance 2018: OECD Indicators, OECD Publishing. DOI:

Rita, C. R. (2000). Teaching social and emotional competence. Children & Schools, 22(4), 246. DOI:

Runhaar, P., Sanders, K., & Konermann, J. (2013). Teachers' work engagement: Considering interaction with pupils and human resources practices as job resources. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 43(10), 2017-2030. DOI:

Schonert-Reichl, K. A., Hanson-Peterson, J. L., & Hymel, S. (2015). SEL and preservice teacher education. In J. A. Durlak, C. E. Domitrovich, R. P. Weissberg, & T. P. Gullotta (Eds.), Handbook of social and emotional learning: Research and practice (pp. 406–421). The Guilford Press.

Seligman, M. E., & Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2014). Positive psychology: An introduction. In Flow and the foundations of positive psychology (pp. 279-298). Springer, Dordrecht. DOI:

Talvio, M., Berg, M., Litmanen, T., & Lonka, K. (2016). The Benefits of Teachers’ Workshops on Their Social and Emotional Intelligence in Four Countries. Creative Education, 7, 2803-2819. DOI:

Talvio, M., Hietajärvi, L., & Lintunen, T. (2022). The challenge of sustained behavioral change – the development of teachers social and emotional learning (SEL) during and after a Lions Quest workshop. In M. Talvio, & K. Lonka (Eds.), International Approaches to Promoting Social and Emotional Learning in Schools: A Framework for Developing Teaching Strategy (pp. 207-219). Routledge, Taylor & Francis. DOI:

Talvio, M., Hietajärvi, L., Matischek-Jauk, M., & Lonka, K. (2019). Do Lions Quest (LQ) workshops have systematic impact on teachers’ social and emotional learning (SEL)? Samples from nine different countries. Electronic Journal of Research in Educational Psychology, 17(2), 465-494. DOI:

Talvio, M., Lonka, K., Komulainen, E., Kuusela, M., & Lintunen, T. (2015). The development of teachers’ responses to challenging situations during interaction training. Teacher development, 19(1), 97-115. DOI:

Taylor, R. D., Oberle, E., Durlak, J. A., & Weissberg, R. P. (2017). Promoting positive youth development through school-based social and emotional learning interventions: a meta-analysis of follow-up effects. Child Dev., 88, 1156–1171. DOI:

Trilling, B., & Fadel, C. (2009). 21st century skills: Learning for life in our times. John Wiley & Sons.

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes. Harvard University Press.

Wigfield, A., & Eccles, J. S. (2000). Expectancy-Value Theory of Achievement Motivation. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 25, 68-81. DOI:

Yeager, D. S. (2017). Social and Emotional Learning Programs for Adolescents. The Future of Children, 27(1), 73–94. DOI:

Zins, J. E., & Elias, M. J. (2006). Social and Emotional Learning. In G. G. Bear, & K. M. Minke (Eds.), Children’s Needs III (pp. 1-13). Bethesda, MD: NASP.

Zins, J. E., Payton, J. W., Weissberg, R. P., & O’Brien, M. U. (2007). Social and Emotional Learning and Successful School Performance. In G. Matthews, M. Zeidner, & R. D. Roberts (Eds.), The Science of Emotional Intelligence: Knowns and Unknowns (pp. 376-395). Oxford University Press. DOI:

Zhou, M., & Ee, J. (2012). Development and validation of the social emotional competence questionnaire (SECQ). International Journal of Emotional Education, 4, 27–42. DOI:

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

30 December 2022

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-959-7

Publisher

European Publisher

Volume

3

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-245

Subjects

Education, educational psychology, pedagogy, positive pedagogy, special education, second language teaching

Cite this article as:

Talvio, M., Makkonen, J., Hietajärvi, L., & Lonka, K. (2022). Benefits of a Social and Emotional Learning Program for Norwegian Teachers. In A. Güneyli, & F. Silman (Eds.), ICEEPSY 2022: Education and Educational Psychology, vol 3. European Proceedings of International Conference on Education and Educational Psychology (pp. 1-14). European Publisher. https://doi.org/10.15405/epiceepsy.22123.1