Abstract

CLIL is a trendy approach towards acquiring foreign languages. Despite its popularity and theoretical background, it is practiced in various ways. This paper aims to reflect on the effects of CLIL learning in practice. The main purpose of this study was to compare teachers' perception on CLIL implementation in three different countries building on a national Spanish project (with the permission of a given authority) and adapting it to Turkish and Italian settings. This paper basically tries to answer the how the perception of the teachers effects the functioning of CLIL type of provision in different educational contexts. A mixed research design was used as the most appropriate method to allow us deeper understanding of the topic. As an instrument we used questionnaires for a quantitative part and a structural interview for a qualitative part of the research. The data showed the importance of the collaboration of teaching staff in terms of creating projects, designing materials, planning lessons and sharing all aspects of teaching learning process for a better implementation of CLIL practice. It drew our attention to the deficiency of training opportunities for subject matter teachers as well as the foreign language teachers. Our results may serve as a guide in a CLIL practice, as well as a self-evaluation tool for the teachers since it revealed certain system of important aspects supporting CLIL implementation relating to material design, planning, administration, monitoring and assessing the process.

Keywords: CLIL, teachers, foreign language teaching, practise, diverse educational contexts

Introduction

Content and Language Integrated Learning (CLIL) is an up-to-date approach for learning languages plus the academic content of other disciplines. Its dual-focused structure leads the teaching of a foreign language through the academic content, and the academic content through the foreign language. In other words, within CLIL contexts, it is important to develop both linguistic and non-linguistic areas. Moreover, ‘achieving this twofold aim calls for the development of a special approach to teaching in that the non-language subject is not taught in a foreign language but with and through a foreign language’ (Eurydice, 2006, p. 7).

Teacher requisites become the main topic of conversation when it comes to CLIL type of provision. Unfortunately, there is still a shortage of qualified teachers according to a recent national report (European Commission, 2014). As a result, providing professional training to pre-service and in-service teachers is of the utmost importance in CLIL settings (Scott & Beadle, 2014). It is also mentioned in the Eurydice report; “teachers applying CLIL need to be qualified in one (or more) non-language subject and have a high command of the foreign language used as the language of instruction” (Eurydice, 2017b, p. 14), therefore, the teaching staff is expected to be proficient in the languages which would be used throughout the academic year in both contexts in order to create the language acquisition environment by communicating with the students in the target language. The lack of well-qualified teachers is not originated from merely the linguistic competence. Teachers’ cognitive competencies, methodology and technique knowledge, as well as their classroom management skills are the elements which limit CLIL. A CLIL teacher is expected to be capable of creating situations where students can debate to solve problems, express their ideas in the target language and improve their creative thinking skills. Linguistic competence should not be sought exclusively as there are other important aspects of teaching and learning process in CLIL contexts.

To sum it up, it is the teacher who is the authority in the class who implements a method to ensure the learning environment. Therefore, their professional training is crucial for the success of CLIL provision (Banegas, 2012). When we consider this reality on a country basis, obviously it shows diversity. For example; in primary education, commonly, one teacher has the responsibility of teaching all the subjects to a particular class including the foreign language and is not asked to have an expertise solely on foreign language teaching. This is the definition for the generalist teacher, and in Italy the primary school teachers are expected to teach all the lessons consisting also foreign language under the condition of proving their level of proficiency in foreign language. Instead, the situation is different in Spain and Turkey since foreign language teaching should be under the control of a specialist teacher who has been graduated from the related departments of the universities and has the expertise on teaching foreign languages (Eurydice, 2017a).

In an attempt to fill this gap, the current article aims to discover the implementation of CLIL considering the perceptions of the foreign language and subject matter teachers in Italy, Spain and Turkey, focusing on the differences as well as similarities of CLIL provision in the tertiary levels of education.

Background

CLIL is more than being an approach for teaching and learning languages, is a concept where all types of bilingual teaching can be involved. This term consists bilingual education, multilingual education, integrated curriculum, language showers, enriched language programs, CLIL camps, soft CLIL, hard CLIL, student exchanges, local projects, partial immersion, total immersion, two-way immersion and double immersion within itself (Mehisto et al., 2008). Having such a generic term is not always an advantage since it creates difficulty in understanding its limits (Alejo & Piquer, 2010) through offering such a definition which is ‘internally ambiguous and unclear’ (Cenoz et al., 2013, p. 244). However, covering all these concepts can be considered as an advantage where students receive solely certain parts of their education through the medium of a foreign language as in immersive type of implementation (Nikula, 1997). From another perspective according to Wolff (2009), consisting all these previous concepts for teaching and learning languages, CLIL should not be solely considered as an approach for this type of teaching since it is concerned both with the content and the language in an integrated way. The focus in CLIL type of learning is neither on the language nor on the content but on the equal blend of these two.

This simultaneous teaching style creates the need for well organized teacher training activities for developing effective CLIL practices (Agustín, 2019). The guidance of a well-trained teacher is of high importance in CLIL settings since the knowledge of the subject area solely will not be sufficient as the teacher needs to teach in the target language and surely foreign language knowledge alone will not be enough for students’ content progress, which make the importance of teacher training a current issue. However, “teacher training institutions in many countries do not yet specifically prepare teachers for CLIL” (Mehisto et al., 2008, p. 21). There are some examples as in Germany and Norway, where CLIL is inserted into into initial teacher training programs for a deep comprehension of the concept (Kelly et al., 2004). Obviously, initial and professional training activities for teachers show differences among European countries. For example, in Italy this type of CLIL training is not possible to be observed even though CLIL is promulgated by the government to be applied in the educational contexts as a national policy to support the learning of a foreign language through the implementation in the last year of upper secondary schools (Eurydice, 2006). There are methodological courses for in-service teachers, which are up to teachers’ own will, depending on their spare time and economic situation since they are not free of charge plus, which require extra time and effort. In Spanish educational context instead, linguistic and methodological support have been provided for pre-service and in-service teachers (Frigols, 2008; Llinares & Dafouz, 2010; Lorenzo, 2010) through the courses organized and funded by the central and regional governments, yet it should not be forgotten that there are huge differences between the course organizations of each region, depending on the regulations of the autonomous region (Lasagabaster & Ruiz de Zarobe, 2010). For example, in the case of Andalusia, summer courses designed by the Regional Ministry of Education, for primary and secondary in-service school teachers considering their needs in terms of language and methodology (Sagrario Salaberri, 2010) whereas in the Madrid region, staying abroad for a summer period is possible for enhancing in-service teachers’ linguistic improvement (Llinares & Dafouz, 2010).

In Turkish CLIL context, it is still early to talk about teacher training programs which is merely designed for CLIL type of implementation within initial or continuing professional development of teachers. However, training options should be offered by the authorities since this type of provision is taken into consideration as a current approach for teaching and learning by the top management members of related schools. Within private schooling the decision to design and monitor the lessons with CLIL approach is up to the directors, whereas it has not been encountered within the mainstream education in Turkey. Hence, Eurydice (2008) reports remark that there is no official CLIL type of implementation.

Problem Statement

CLIL implementation varies from country to country even from region to region in most of the cases. Therefore, it is scarcely possible for an educative system to monitor its implementation processes like another one plus ‘there is no single blueprint of content and language integration that could be applied in the same way in different countries’ (Baetens Beardsmore, 1993, p. 39). Educational policies, legislatives, and teacher training programs of each country create differences within CLIL practice where essentially ‘it needs to be tailor-made to fit the national/local circumstances’ (Takala, 2002, p. 42). Yet, “there is no way we may know the differences of CLIL implementation” (Coyle, 2007, p. 5), unless we have a deep prospecting about the organization behind CLIL teaching which does not only depend on teacher qualifications but also their perceptions. And the perceptions of the teachers might differ in terms of the society, educative background, and teaching and learning habits among different countries. Starting from this point of view, understanding teacher perspectives would enhance the success of CLIL provision. Therefore, this study focuses on one of the elements which may affect the success of CLIL practice in an international level.

Research Questions

This research is designed with a view to answering the following main question on a three-year period basis; ‘How does the management among school departments or members effect the functioning of CLIL type of provision?’ through the description and definition of the components of educative systems and the interaction among themselves. It will answer these following sub-questions in detail with the aim of revealing the response of the main question:

- What type of connection is there between the involvement of the top management and the proper functioning of the systems?

- Are the teachers satisfied with the training opportunities they are offered?

- How are the academic and non-academic results perceived from the educational community in terms of fulfilling the objectives which are set for students in linguistic and non-linguistic areas?

Purpose of the Study

CLIL type of provision would be tackled in detail throughout this paper with a multidimensional point of view at an international level, considering the perceptions of content and language teachers. The main objective of this paper is to reveal the differences in teacher perceptions on CLIL considering its all procedures in Italy, Spain and Turkey in tertiary levels of education. Within the theoretical framework teacher training policies are aimed to be examined to have a clear point of view about CLIL in each country to lead a better understanding of the present research. Within the empirical framework, the intention is to enlighten the scope of the work, organization, design of data collection tools, selection of the schools, depiction of the data collection processes as well as the description of the collaboration with the schools in three mentioned countries.

Research Methods

This research makes use of mixed method as a research methodology, which consists, data collection and analysis, as well as the integration of findings and formulation of inferences, based on the use of both qualitative and quantitative approaches or methods (Hesse-Biber & Johnson, 2015). Johnson et al. (2007) describe mixed methodology as a combination of qualitative and quantitative research approaches “for the broad purposes of breadth and depth of understanding and corroboration” (p. 123) which creates a profound and better understanding to the research problem (Creswell & Plano Clark, 2007). Quantitative research is regarded as the deductive research design which starts with a hypothesis of a research problem and focused on the analysis of quantifiable data by standardized data collection tools (Rovai et al., 2014). Whereas, qualitative research includes the perspective of the researcher which ends with a hypothesis, focuses on the diversity and multiplicity and makes use of the researcher as a data collection tool (Charmaz, 2011; Hendl, 2008).

This research utilizes Convergent Parallel Design QUAN – QUAL Findings Interpretation model which consists the simultaneous collection of quantitative and qualitative data with a separate analyse of the data as well as the comparison of the results which then would lead more confidential research results (Creswell, 2014; Oppermann, 2000).

Surely, the research design shows different characteristics according to each country in terms of the participants and implementation of the questionnaires and interviews.

Participants

The target group selection was done with the consideration of the existence of CLIL type of implementation in the related school. In Spain, it has been administered in the bilingual centers with CLIL approach whereas in Turkey and in Italy the first preference has always been in favor of the public schools. In Italy, five public schools have been found to conduct the research with one private school whereas in Turkey private schools have been selected to work with since in the mainstream education this type of provision had not been encountered.

In Italy the data gathered from one private school called Liceo Linguistico Paritario Keynes Institute and four other public schools, namely; Educandato Statale Maria Adelaide, Istituto Magistrale Statale Regina Margherita, Liceo Albert Einstein and Liceo Vittorio Emanuele III. And in Turkey, four private schools have been contacted. The common characteristics of these schools are their making use of another foreign language for CLIL practice more than English, such as French and German. That is the reason of the survey translations have been managed through considering the conditions the schools are offering. For example, instead of asking questions for English language teaching, the participants are asked questions about foreign language teaching. In Spain, eight bilingual centers were contacted to conduct the research. The administration of the questionnaires has been done and interviews have been completed by a research group, so, the results from Spain would be gathered from the book called ‘Influencia de la política educativa de centro en la enseñanza bilingüe en España’ that is published by Ortega-Martín et al. (2018) with the cooperation of Ministry of Education and British Council.

Instruments

The data collection instruments for this study were designed by a group of professors and researchers in Spain, and supervised by three professors from University of Granada, namely; Ortega-Martín et al. (2018) and implemented in all of the regions of Spain with the aim of revealing the perceptions of teachers on CLIL and accordingly improve this type of teaching.

The translation and adaptation of the instruments were done by the author. At the end, the translations of the questionnaires were validated by one professor and one PhD student in the field of educational sciences in Italy, and two PhD students in Turkey in the same area of expertise.

Qualitative data collection has been managed through the open-ended questions as well as the interviews performed with the managers; aiming to provide the ideas of the teachers about the bilingual programs or CLIL and the opinions of managers. Moreover, at the end of each survey two open ended questions were included in order to discover the ideas of the participants for the improvement of the CLIL program. The questions are related to the CLIL implementation in the centers in Spain, at public and private schools in Italy and Turkey, the amount of L2 usage during the classes, the cooperation among the teaching personnel, the participation to the international projects and the satisfaction of the teachers and the students from the way CLIL is implemented in the educational area.

There are two different questionnaires, designed for each group of teachers each with six different categories; top management, coordination, and academic and non-academic results of the system. Each group has a unique list of items, as well as the overlapping questions since there were common areas of interest (Hughes et al., 2018).

For quantitative data collection, five surveys have been administered to two different groups of respondents, namely; subject matter teachers and foreign language teachers in all the mentioned countries. In the surveys, the participants were asked to express their opinions and perceptions using a Likert Scale (1 = totally disagree; 2 = disagree; 3 = neither agree nor disagree; 4 = agree; 5 = totally agree) with a blank space left to enable them clarify their ideas if they desire. These instruments enabled a methodological triangulation and personal data (Aguilar et al., 2015) that allow to obtain a multidimensional perspective of the focus of interest of this research (Hughes et al., 2018).

Findings

The findings of the research are presented here through integrating the qualitative and quantitative data from each country. The answers of respondents are set in two different categories, namely: the functioning of top management, and academic and non-academic results. Each country is examined individually before presenting the comparison of all three countries.

Top management

CLIL teachers of Italy do not seem to be satisfied neither with the educative opportunities provided by managers, nor with the system communication channels used in Italy. According to the collected data, they do not receive support from their managers for the improvement of the quality. Interestingly, the managers reported the same issue, through mentioning that they expect economical and organizational support from the government to train first themselves and then their teachers. It is clear in Italy; each member of educative system has his/her own training responsibility. In this case it contradicts with the regulations of Italian Ministry of Education.

What declared by the manager of a participant school in Italy about training opportunities received on CLIL teaching for managers, seems summarizing the situation in Italy quite well: “No, I must say (…) we did have no preparation on CLIL. The only preparation was precisely self-enhancement in the sense that we have read all the documents of the Ministry and etc. Then there were meetings of coordination at a provincial level, at a regional level. But a real training… no…” (R.M., Italy).

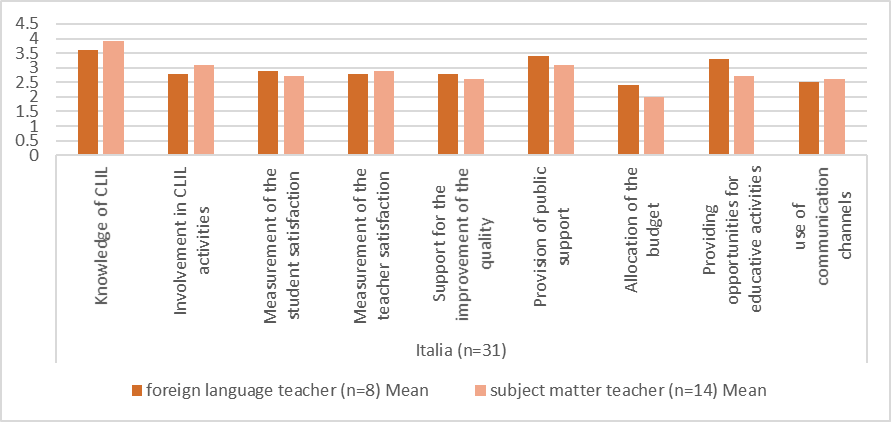

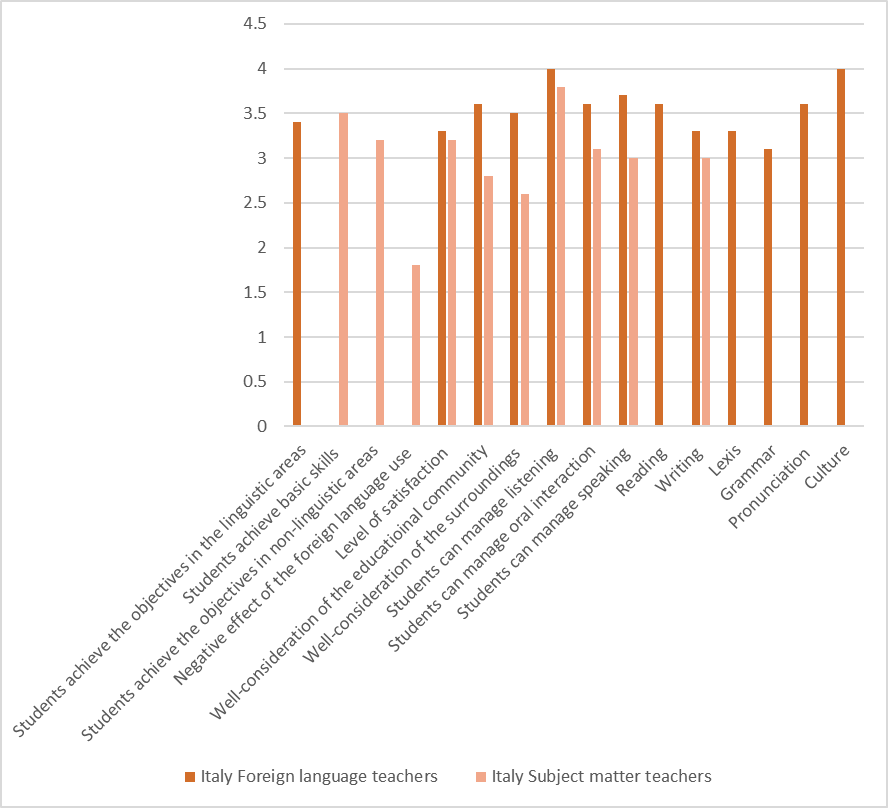

What’s more, Italian teachers seem to be satisfied with managers’ CLIL knowledge even though they do not find sufficient their involvement in CLIL type of activities. And managers are aware of this reality, plus, they report during the interviews that, there is a connection between the teachers’ motivation and their training; information sharing makes them confident on methods and committed to CLIL program (Figure 1).

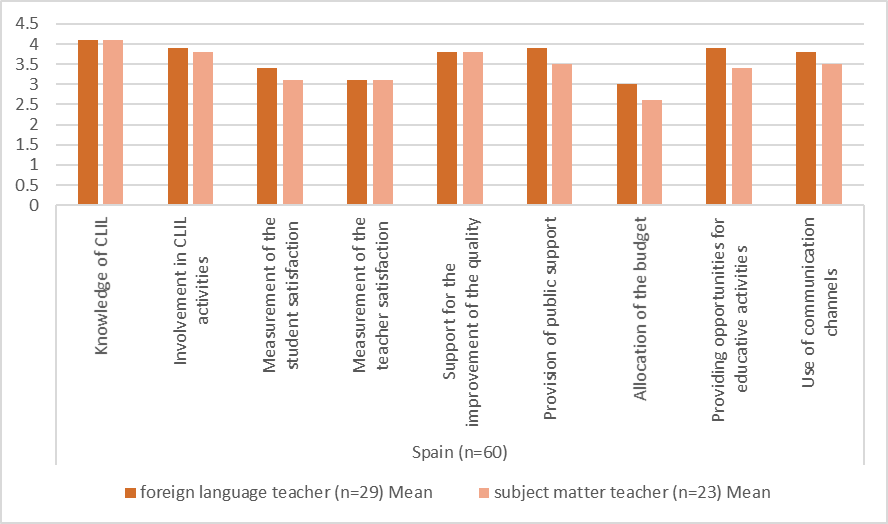

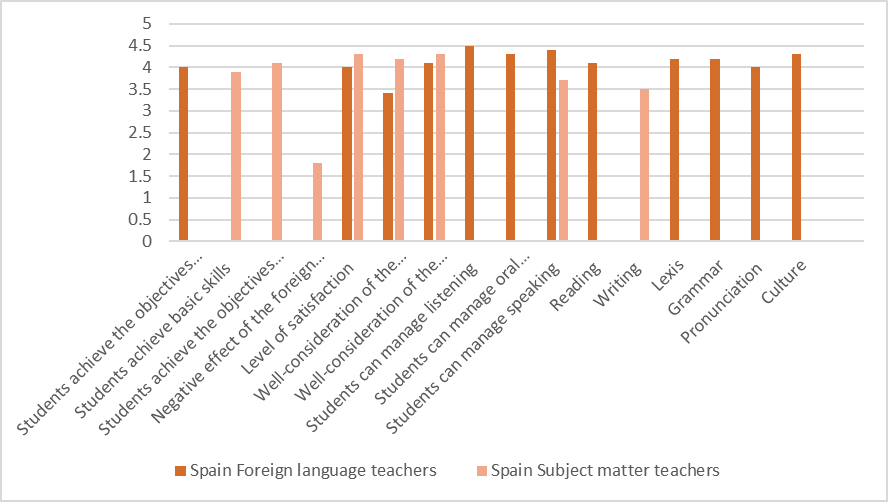

In Spain, the data demonstrates that participants have a deeper awareness of the potentialities of the CLIL methodology as well as of the improvements of the system thanks to the competencies acquired (Figure 2). On the contrary of Italy, the teachers are satisfied with the educative opportunities provided by managers as well as the use of communication channels. They do not seem to be content with the financial support to their professional growth as well as the one that managers need to receive, but the managers reported that they do their best to fill this gap, at least through their personal efforts. Though the lack of specific training, the members of the top management are likely to face all situations. The words of a director from Spain are in furtherance with this statement: "A director is prepared for everything, but there is no specific training for this" (ED5.E, Spain).

Moreover, it wouldn’t be wrong to mention that foreign language and subject matter teachers are satisfied with their managers’ knowledge of CLIL as well as their attendance in CLIL type of activities.

It is also observed that the teachers of the Spanish system are not satisfied with the measurement of the student and teacher satisfaction. However, it is worth mentioning that there is an online platform in order to measure the level of satisfaction of students and parents: “We have a self-assessment that parents and students answer from the website” (ED2.E, Spain).

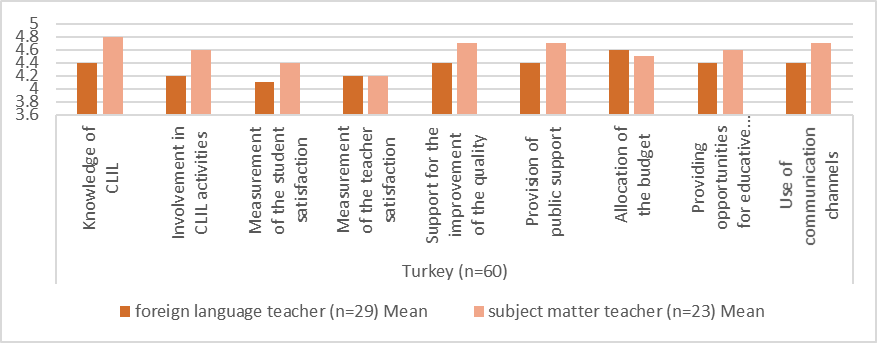

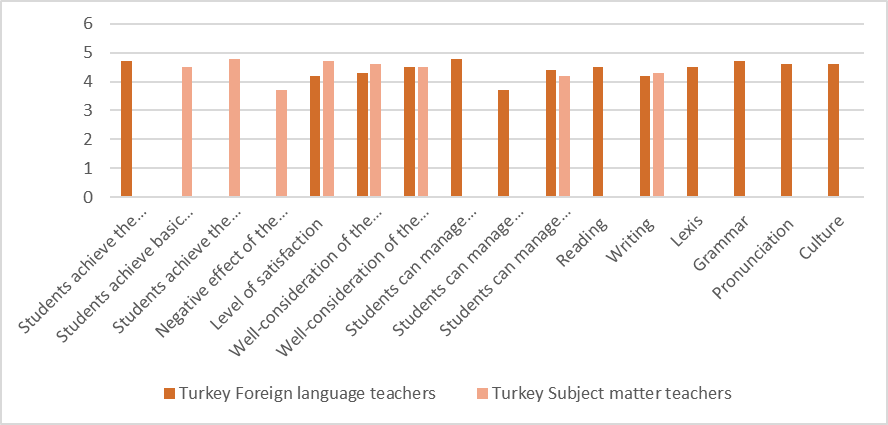

In Turkey, teachers are satisfied with the educative activities they receive as well as the use of communication channels (Figure 3). The functioning of CLIL approach in their schools seems to be appreciated. Turkish teachers are generally satisfied with the supports provided and coordination among themselves even though the lack of training for managers. What is fundamental, anyway is the knowledge of the role of the language in education as possessed by managers, that helping monitor the CLIL approach.

“Yes, we are well informed and prepared to address the issues and needs of a bilingual school. The allotted class hours alone testify to the commitment the school has towards supporting our students’ being bilingual. There is also considerable time and effort given to professional development on second language teaching skills.” (R.C., Turkey)

Measurement of satisfaction can be considered as an area to improve in Turkish CLIL context since teachers do not seem to be content about the amount of feedback they receive from their students and the one they give. Finally, on the contrary of Italy and Spain, Turkish teachers seem to be happy about the financial support they receive.

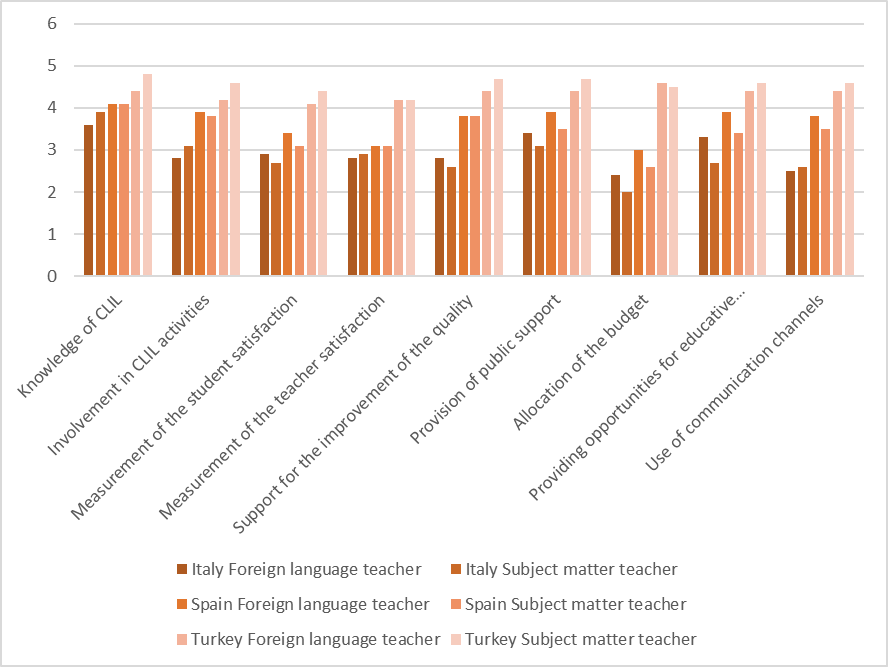

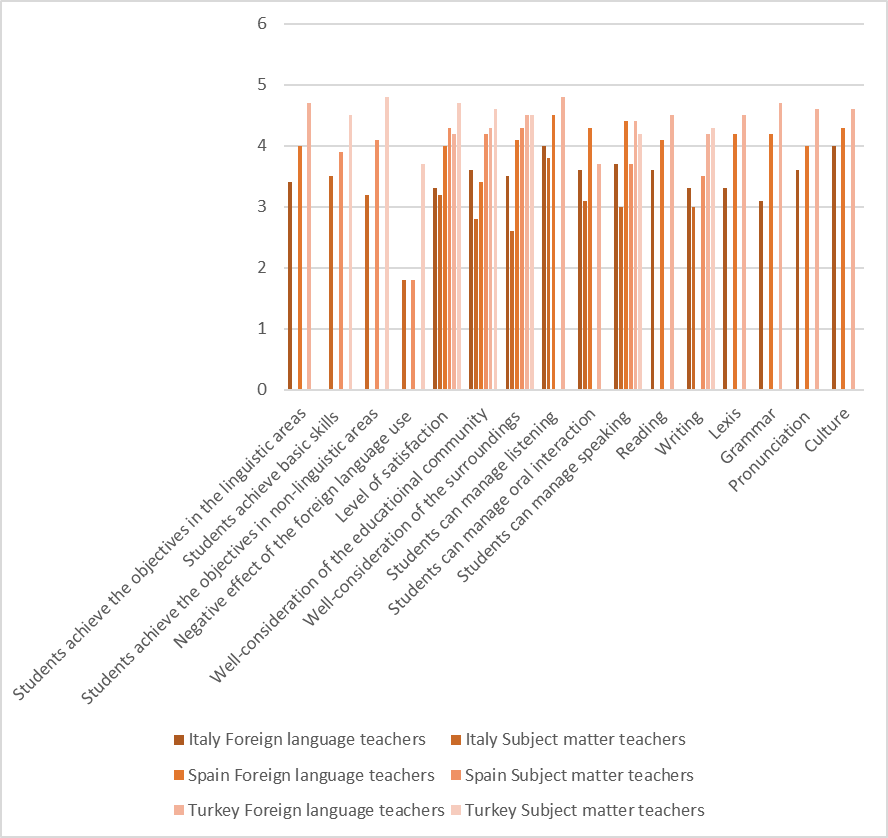

A general overview of the perceptions of Italy, Spain and Turkey in terms of the perceptions of the teachers in CLIL settings is shown in Figure 4, there we see that the top management has the adequate knowledge of the CLIL approach even though there is no such training as to leading and coordination.

It is perceived that, there is motivation and commitment but there is lack of support for training in the case of Italy. The reason for that could be also the proficiency level of the teachers in the foreign language. The 22,6 % of Italian teachers have a C1, while the %25,8 have a C2 level of proficiency. The ratio is %56 for foreign language teachers with a C2 proficiency level in Turkey and % 31 of the teachers claimed to have a C1. As to Spain the %47, have a C2 level of proficiency. It’s obvious that there is a connection between a teacher competence in foreign language and the implementation of CLIL.

Teachers

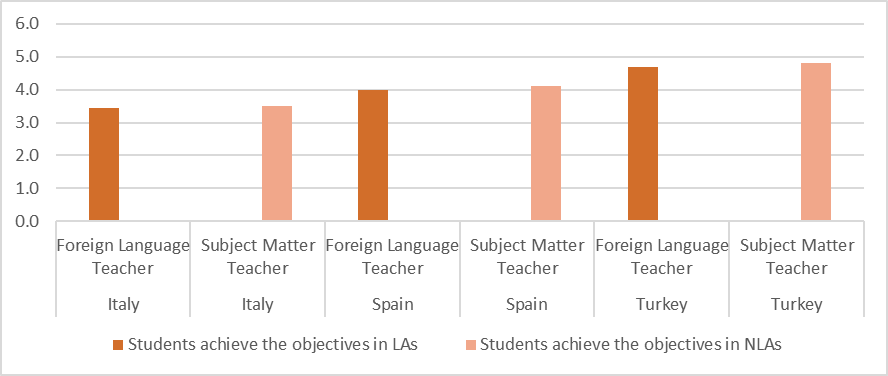

Here the perceptions of subject matter teachers and foreign language teachers about the academic and non-academic results of students are presented. Italian teachers represent neither agreement nor disagreement on students’ achieving objectives in foreign language as well as gaining basic skills as shown in Figure 5. Whereas, coordinators agree on the fact that students achieve the learning objectives of non-linguistic areas.

None of the participants record an agreement on the negative effect CLIL may have on the academic success of the students, in fact subject matter teachers show a total disagreement with this statement. When it comes to the satisfaction of the educational community about CLIL practices and provisions; interestingly coordinators show a dissatisfaction whereas mangers and teachers do not show neither agreement nor disagreement. This may originate from the opinion that they are not yet ready for the right implementation of CLIL: “Satisfied… in my opinion, not satisfied or can't be satisfied because we are still at a stage, according to me initial” (A.A., Italy).

The CLIL practice being implemented at schools in Italy is neither well-considered from the educational community nor from the environment according to the subject matter teachers. The responses to these questions from teachers show neither agreement nor disagreement, however, they all disagree about the positive consideration of the CLIL practices by the environment such as the locality, local press, etc.

As to the evaluation of CLIL program by teachers neither their agreement nor their disagreement on students’ oral interaction competencies as well as their reading, writing and speaking skills is reported. With regards to their listening skills, foreign language teachers show an agreement tough, like their managing cultural objectives set by the teachers.

As it can be seen in Figure 6, Spanish educational community show a great level of satisfaction with the CLIL program unlikely the Italian one. Moreover, they do not agree about the negative effect CLIL on content learning. As in interviews they mention the positive effects it has on students’ academic and linguistic success: “Bilingual groups have good results and are valued positively” (ED3. E., Spain)

What’s more, the teachers agree on the statement that students manage reaching the learning objectives of the linguistic and non-linguistic areas. Surely, they do not underestimate the students’ commitment and autonomous learning: “Learning is directly proportional to the student’s performance and dedication” (PANL.PA., Spain).

Another important component which is worth mentioning in Spanish context is the fact that the CLIL practice in bilingual centers has a positive impression on the educational community; subject matter teachers and foreign language teachers are showing neither agreement nor disagreement on this statement. However, it’s worth mentioning that local environment and press show agreement on this item.

Considering the foreign language teachers views, it is worth mentioning that the students manage most of the learning objectives set by their teachers; as, listening, speaking, writing and reading skills plus they also manage grammar, lexis and pronunciation as well as the objectives of cultural elements. Whereas, the subject matter teachers do not show any agreement or disagreement on students’ speaking or writing skills.

In Turkey, it is clear from the results that, there is a general satisfaction linked to academic and non-academic results of the CLIL practice (Figure 7). All the educational community agree on students’ achieving the linguistic and non-linguistic results as well as the learning objectives which are set by their teachers.

When it comes to the negative effects of the CLIL provision, interestingly foreign language teachers show agreement on this item while subject matter teachers do not mention an agreement or disagreement. On the other hand, foreign language teachers seem to be satisfied with CLIL practice like subject matter teachers and managers. Those responses are interesting as they are representing a dilemma. Foreign language teachers’ reporting negative effect on foreign language usage during the classes for teaching content knowledge then showing a considerable satisfaction on the bilingual systems’ functions lead to an ambiguity in Turkish CLIL setting in terms of these two questions which teachers are asked to rate.

There is a positive opinion about the program as given by the educational community and local environment as all participants agree. There is an obvious connection with the satisfaction of the teaching staff making an effort on bilingual teaching.

With regards to the improvement of students’ skills on speaking, writing, reading and listening in foreign language, the teachers share the same opinion since they all agree their success on grammar, vocabulary, pronunciation as well as the management of the cultural aspects.

A comparison of the perceptions on academic and non-academic results in all three countries is shown in Figure 8. The students’ academic success is limited by the negative opinion expressed by the teaching staff about the CLIL implementation. Obviously, there are difficulties, students may face with foreign language instruction given during classes especially in Turkey. In Spain and Turkey, there is general positive perception on the provision of CLIL by the educational community as well as the local community whereas in Italy, it is still difficult to get a common perception since subject matter teachers do not agree on neither of the statements while coordinators support them, while managers and foreign language teachers do not share an opinion on these statements.

There is a slightly higher agreement on student success and achievement of the learning objectives in Spain and Turkey as compared to Italy. Here most teachers would prefer not to share an opinion on these statements consisting students’ reaching their academic goals.

When the perceptions of the participants about the results are analyzed detailly, in Figure 9; the satisfaction of subject matter teachers on students’ reaching non-linguistic learning objectives attracts the attention in Turkey as well as the foreign language teachers’ agreement on students’ success when achieving the learning objectives of linguistic areas.

In Spain, the teachers of both areas agree on the success of students whereas in Italy, teachers show neither agreement nor disagreement on the same item. Considering the collected data, it wouldn’t be incorrect to mention that, the teachers in Turkey show the highest agreement on students’ academic success, which is followed by Spain and Italy respectively.

Conclusion

The current results show clearly the importance of the collaboration of teaching staff in terms of creating projects, designing materials, planning lessons and sharing all aspects of teaching & learning process for a better implementation of CLIL practice. It also draws our attention to the deficiency of training opportunities for teachers.

It highlights the adequate knowledge the teaching staff have, thanks to their personal effort for their professional growth. In other words, it does focus on neither the dark side nor the bright side of CLIL practices. It aims to define CLIL provision in its own reality and pace within the context of each country with a multidimensional approach which can be defined as a still working progress approach (Lorenzo et al., 2009).

From this point forth, our data may serve as a guide to the educational settings with CLIL practice, as well as a self-evaluation tool for the managers, and teachers with the same type of implementation, since it requires the quantitative information about the importance of the role of top management, and academic and non-academic results as well as the qualitative information in a complementary way. The data we present may be considered as a meaningful contribution to the research literature and a source of information for the teachers in practice as well as the professionals in the field.

The current research may be considered as a starting point to discover CLIL implementation. Though the number of researches done in the area of CLIL, we may come to the conclusion that, there is still the need to understanding the effectiveness of CLIL, focusing on the language proficiency and the content knowledge of students through focusing on the evaluation aspects of CLIL programs (Cenoz et al., 2013; Dalton-Puffer et al., 2010; Lasagabaster & Sierra, 2010; Seikkula-Leino, 2008).

On the basis of this conclusion, this research is to be considered as an introduction into a practice like every other research. Besides, it may also be considered as an inspiration for further investigation and for a better and detailed comprehension of CLIL practices in different settings.

Considering the situation of our world today, we are obliged to change our current educative systems into digital ones. These changes gave us no other chance but keep pace with. Bearing this in mind, it would be valuable to design a research for understanding the new future structure of CLIL.

Acknowledgments

This research was carried out during PhD studies of the first author whose studies were funded by the Ministry of Education, University and Research of Italy. It was designed based on the national Spanish project which was supported by the Ministry of Education, Culture and Sport and the British Council by a group of professors, researchers and PhD students at the bilingual centres.

References

Aguilar Gavira, S., & Barroso Osuna, J. (2015). La triangulación de datos como estrategia en investigación educativa. [Data triangulation as a strategy in educational research] Píxel-Bit. Revista de Medios y Educación, 47, 73-88.

Alejo, R., & Piquer, A. (2010). CLIL Teacher Training in Extremadura: A needs analysis perspective. In D. Lasagabaster & Y. Ruiz de Zarobe (Eds.), CLIL in Spain: Implementation, Results and Teacher Training (pp. 219-242). Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

Agustín, M. P. (2019). Meeting CLIL teachers’ training and professional development needs, NABE Journal of Research and Practice, 9(3-4), 119-127. DOI: 10.1080/26390043.2019.1634961

Baetens Beardsmore, H. (Ed.). (1993). European models of bilingual education. Multilingual Matters.

Banegas, D. L. (2012). CLIL teacher development: Challenges and experiences. Latin American Journal of Content and Language Integrated Learning, 5(1), 46–56. DOI: 10.5294/laclil.2012.5.1.4

Cenoz, J., Genesee, F., & Gorter, D. (2013). Critical analysis of CLIL: Taking stock and looking forward. Applied Linguistics, 35(3), 243–262

Charmaz, K. (2011). Grounded theory methods in social justice research. In Handbook of qualitative research (pp. 359–380). Sage.

Coyle, D. (2007). Towards a connected research agenda for CLIL pedagogies. The International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 10, 543–62.

Creswell, J. W. (2014). A concise introduction to mixed methods research. Sage.

Creswell, J. W., & Plano Clark, V. L. (2007). Designing and conducting mixed methods research. Sage.

Dalton-Puffer, C., Nikula, T., & Smit, U. (2010). Language Use and Language Learning in CLIL Classrooms. John Benjamins Publishing Company.

European Commission. (2014). Improving the effectiveness of language learning: CLIL and computer-assisted language learning. London, England.

Eurydice (2006). Content and Language Integrated Learning (CLIL) at School in Europe. Education, 33. DOI:

Eurydice (2008). Key Data on Teaching Languages at School in Europe. Annals of Physics, 54, 258.. DOI: 10.2797/12061

Eurydice (2017a). Key features of the Italian education system. https://eacea.ec.europa.eu/national-policies/eurydice/content/italy_en

Eurydice (2017b). Key Data on Teaching Languages at School in Europe. DOI:

Frigols, M. J. (2008). CLIL Implementation in Spain: an approach to different models. CLIL e l’apprendimento delle lingue Le sfide del nuovo ambiente di apprendimento (CLIL and language learning The challenges of the new learning environment). Università Ca’ Foscari Venezia.

Hendl, J. (2008). Kvalitativní výzkum [Qualitative research]. Portál.

Hesse-Biber, S., & Johnson, R. B. (2015). The Oxford Handbook of Multimethod and Mixed Methods Research Inquiry. Oxford University Press.

Hughes, S., Ortega-Martín, J., & Madrid, D. (2018). Proyecto de investigación para la evaluación de los programas AICLE. In J. Ortega-Martín, S. Hughes & D. Madrid, Influencia de la política educativa de centro en la enseñanza bilingüe en España (pp. 31-39). [Investigation Project for the Evaluation of CLIL programs]. Ministerio de Educación, Culture y Deporte Secretaría de Estado de Educación, Formación Profesional y Universidades Centro Nacional de Innovación e Investigación Educativa CNIIE Edita.

Johnson, R. B., Onwuegbuzie, A. J., & Turner, L. A., (2007). Toward a definition of mixed methods research. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 1, 112–133.

Kelly, M., Grenfell, R., Allan, C., Kriza, C., & McEvoy, W. (2004). European profile for language teacher education: A frame of reference. European Commission.

Lasagabaster, D., (2010). English achievement and student motivation in CLIL and EFL settings, Innovation in Language Learning and Teaching, 5(1) , 3-18.

Lasagabaster, D., & Ruiz de Zarobe, Y. (2010). Ways forward in CLIL: Provision Issues and Future Planning. In D. Lasagabaster, & Y. Ruiz de Zarobe (Eds.), CLIL in Spain. Implementation, Results and Teacher Training (pp. 278-293). Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

Llinares, A., & Dafouz, E. (2010). Content and Language Integrated Programmes in the Madrid Region: Overview and Research Findings. In L. David & Y. Ruiz de Zarobe (Eds.). CLIL in Spain: Implementation, Results and Teacher Training. Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

Lorenzo, F. (2010). CLIL in Andalusia. In D. Lasagabaster & Y. Ruiz de Zarobe (Eds.), CLIL in Spain. Implementation, Results and Teacher Training (pp. 2-27). Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

Lorenzo, F., Casal, S., & Moore, P. (2009). The Effects of Content and Language Integrated Learning in European Education: Key Findings from the Andalusian Bilingual Sections Evaluation Project. Applied Linguistics, 31(3), 418-442. DOI:

Mehisto, P., Marsh, D., & Frigols, M. J. (2008). Uncovering CLIL: Content and language integrated learning in bilingual and multilingual education. Macmillan Education.

Nikula, T. (1997). Terminological considerations in teaching content through a foreign language. In D. Marsh et al. (Eds.), Aspects of Implementing Plurilingual Education (pp. 5-8). http://userpage.fu-berlin.de/elc/bulletin/9/en/marsh.html

Oppermann, M. (2000). Triangulation — a methodological discussion. International Journal of Tourism Research, 2(2), 141-145. DOI: 10.1002/(SICI)1522-970(200003/04)2:2<141::AID-JTR217>3.0.CO;2-U

Ortega-Martín, J. L., Hughes, S., & Madrid, D. (2018). Influencia de la política educativa de centro en la enseñanza bilingüe en España [Influence of the center's educational policy on bilingual education in Spain].

Rovai, A. P., Baker, J. D., & Ponton, M. K. (2014). Social Science Research Design and Statistics. Watertree Press LLC.

Sagrario Salaberri, R. (2010). Teacher Training Programmes for CLIL in Andalusia. In D. Lasagabaster & Y. Ruiz de Zarobe (Eds.), CLIL in Spain: Implementation, Results and Teacher Training. Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

Scott, D., & Beadle, S. (2014). Improving the effectiveness of language learning: CLIL and computer assisted language learning.

Seikkula-Leino, J. (2008). CLIL Learning: Achievement Levels and Affective Factors. Language and Education, 21(4), 328-341.

Takala, S. (2002). ‘Positioning CLIL in the wider context’, in D. Marsh (ed.), CLIL/EMILE—the European Dimension: Actions, Trends and Foresight Potential, European Commission. DG EAC.

Wolff, D. (2009). Content and Language Integrated Learning. In K. -F. Knapp, & B. Seidelhofer in cooperation with Henry Widdowson (Eds.), Handbook of Foreign Language Communication and Learning (pp. 545-572). Mouton de Gruyter.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

24 November 2020

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-952-8

Publisher

European Publisher

Volume

1

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-370

Subjects

Education, educational psychology, pedagogy, positive pedagogy, special education, second language teaching

Cite this article as:

Korbek, G., & Wolf, J. (2020). Teaching Perspectives on CLIL in Different Educational Contexts: Italy, Spain and Turkey. In P. Besedová, N. Heinrichová, & J. Ondráková (Eds.), ICEEPSY 2020: Education and Educational Psychology, vol 1. European Proceedings of International Conference on Education and Educational Psychology (pp. 247-262). European Publisher. https://doi.org/10.15405/epiceepsy.20111.23