Abstract

Research conducted on the popularity of teaching profession with school-leavers has indicated on low popularity and young people’s little interest in the profession. This may have several reasons but one of the most dominating indicators is the impression teachers themselves make of their work. The current study was triggered by the results of a preceding study, which explored final-year students’ perceptions and attitudes towards teaching profession. This paper explores how teachers perceive their profession and which image and attitude they forward to their students. 226 primary and secondary teachers were questioned. Their answers were compared to their students’ answers collected a year before. The results revealed that teachers perceive the reputation of the teaching profession in society as being low. Even though most of them love their job, they would not encourage young people to pursue a career in teaching, mostly because of the low salaries and low reputation. Despite the teachers’ perception of their job having low reputation, several steps have been taken statewise to recognise their good work.

Keywords: Attitudes, career motivations, job satisfaction, occupational prestige, perceptions, teaching profession

Introduction

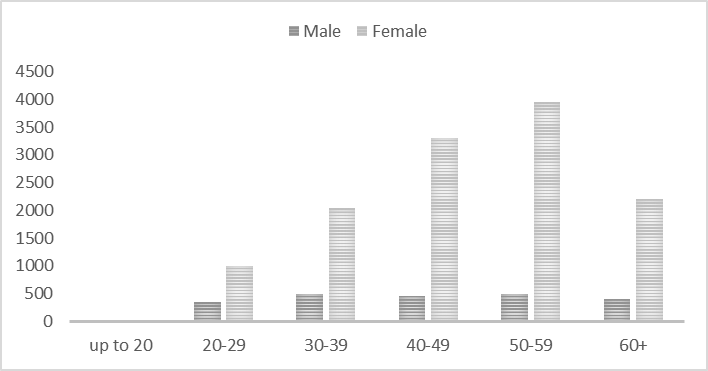

Teaching workforce is rapidly ageing in many parts of the world including Estonia (OECD, 2014). Like many other countries, such as Italy, Bulgaria and Latvia, Estonia may be facing a shortage of teachers ten-fifteen years from now. In the 2016/2017 academic year, 48% of 14,581 teachers working in general education were above 50 years of age, while the smallest cohort of teachers belonged to the age group 20–29 (see Figure 1) (Republic of Estonia 100, 2018).

According to a report by the OECD (2014), Estonia is one of the few countries with the oldest and still ageing teacher population. The small number of young teachers in Estonian schools is a direct result of a lack of interest in the teaching profession among young people (Saks et al., 2016), which in turn may be the result of the low level of prestige of the profession in society (Õpetajaameti kuvand ja atraktiivsus, 2016; TALIS, 2014). This may lead to a situation where large numbers of retiring teachers are difficult to replace with new recruits, which may further worsen existing teacher shortages (OECD, 2014). Being aware of the factors that influence the choice of the teaching career provides a starting point for attracting new teachers and developing teacher education programmes that serve the needs of future teachers (Fray & Gore, 2018). In order to explore the attitude of students toward teaching profession, a study was conducted in 2014 (Saks et al., 2016) where 18–19-year-old students were questioned about their perceptions of teaching profession and whether they would pursue a career in teaching. The study revealed that students had a rather realistic albeit negative attitude towards teaching profession. They adequately estimated the work of teacher and noticed the problems and difficulties teachers had to face on a daily basis. Yet, students’ attitude towards the profession may not only be affected by what they see every day at school but also by the messages teachers themselves send about their work (Hutchinson & Johnson, 1994), their self-concept and self-evaluation (Judge & Bono, 2001), job satisfaction (Saks et al., 2016) and the general reputation of the job.

In order to obtain deeper understanding of the roots of student reluctance to enter teaching profession, a study was launched to explore the attitudes and mentality of teachers towards their work. Understanding teachers’ perceptions of their own profession and their motivations to do the job, enables us to adopt measures to communicate more positive messages and popularize the profession among young people.

In this paper we focus on exploring the perception of teaching profession among teachers with the aim of measuring their job satisfaction, how they evaluate themselves as teachers, and whether and how they encourage students to pursue teaching profession. The research is grounded on the following theoretical subtopics – occupational prestige, career motivations and job satisfaction, which will now be unpacked in greater detail. At the end of the section, the research questions are formulated.

Occupational prestige

Although the teacher’s job has been apportioned respect and importance through centuries, recent decades have shown a decline in public perception and respect for teachers (Everton et al., 2007). Cunningham (1992) traced the image of teachers and identified recurring concerns with status, poor pay and problems with teacher supply. Professionally speaking, status refers to the social standing of various groups, and is connected to prestige and desirability of the occupation (Fuller et al., 2013). Power, money and fame are considered primary drivers of status (Hall & Langton, 2006). Raising the status of teachers can be effective only when secondary drivers – training, skill, expertise and social influence – contribute to the primary drivers. What seems to affect attitudes to teachers and teaching, is public perceptions and people’s attitudes to teaching profession (Everton et al., 2007).

Occupational prestige was defined by Hoyle (2001) as the public perception of the position of an occupation compared to other occupations. There are many different factors involved which all contribute to determination of occupational prestige, and these factors together form occupational image. Hoyle argues that the level of prestige is shaped by the perceived image of teacher, which ultimately originates from teachers’ immediate clients – children. Proceeding from that it can be claimed that teachers’ relations with students have the strongest impact on the image and prestige of teachers.

Several studies have revealed a surprising finding on public perception of teaching profession, which is higher compared to teachers’ own perceptions of their job (Ingersoll, 2001; Õpetajaameti kuvand ja atraktiivsus, 2016; TALIS, 2014). Teachers tend to feel a gap between the status of teaching and other high-status professions (Fuller et al., 2013). Hargreaves et al. (2006) showed that teachers estimate the status and esteem afforded by colleagues and parents rather than that of public opinion. The feeling of being valued leaves its mark on job satisfaction and career motivations.

Teachers’ career motivations

Numerous studies have explored career motivations and commitment of student-teachers and teacher candidates (Bergmark et al., 2018; Charalambos, 2017; Fray & Gore, 2018; Heinz, 2015; Kidd et al., 2015), but there are much fewer studies concerning attitudes of practising teachers towards their career.

In addition to reputation and job satisfaction, motivation in teaching plays an important role. Most of motivations for why people may or may not consider pursuing career in teaching are distinguished as intrinsic, altruistic and extrinsic (Heinz, 2015). According to self-determination theory (Deci & Ryan, 1985), intrinsic motivation refers to doing something because it is inherently interesting and enjoyable for the individual. Internally motivated teachers also motivate their students. Intrinsic motivation may involve passion for teaching or interest in the subject matter taught (Struyven et al., 2013), enjoyment gained from teaching (Reeves & Lowenhaupt, 2016), suitability for career in teaching (Chong & Low, 2009), and feeling of accomplishment (Ralph & MacPhail, 2015). But it may also include development of knowledge and professional skills (Struyven et al., 2013) and intellectual stimulation (Jungert et al., 2014).

Altruistic motivation is comprehended as something socially worthwhile and important for contributing to wellbeing of society and mankind (Heinz, 2015). The impulse to teach has been considered fundamentally altruistic as it represents individual’s desire to share what he values and to empower other people (Kohl, 1984). The main altruistic motivations for working as teachers are serving others (Yüce et al., 2013), contributing to society, and supporting students (Jungert et al., 2014). The professional motivation of teachers has been claimed to affect their students’ behaviour, intellectual development and aspirations (Addison & Brundett, 2008). Several studies suggest that teaching career is attractive above all for those who desire intrinsic rewards and who approach teaching as a calling (Hayes, 1990; Osguthorpe & Sanger, 2013). Earlier studies (e.g. Köning & Rothland, 2012; Wong et al., 2014) have shown that intrinsic motivation has the biggest influence on selecting and remaining in teaching. Interest in subject matter and desire to pass on their knowledge are the main intrinsic factors that urge youngsters to choose career in teaching (e.g. Flores & Niklasson, 2014; Hayes, 1990).

Extrinsic motivation refers to doing something in order to attain a desired outcome or reward (Ryan & Deci, 2000). Fray and Gore (2018) distinguish two categories for extrinsic motivation: the first one relates to lifestyle choices outside of work, such as balance between work and family commitments (Struyven et al., 2013), flexible working hours and holidays (Aksu et al., 2010); and the second relates to work conditions, such as career prospects (Cheung & Yuen, 2016), income (Jungert et al., 2014), and working conditions (Yüce et al., 2013). Heinz (2015) brought out several subdivisions for extrinsic motivations: the compatibility of teaching profession with family responsibilities, teaching profession as a “springboard”, the teaching profession as a “fallback”, influence of family members and socio-cultural influences. Extrinsic reasons, like status, pay and job security do not usually prevail as the main motivations compared to intrinsic and altruistic motives (e.g. Hayes, 1990; Heinz, 2013; Watt et al., 2012). However, there are several examples in countries like China, Turkey or Malaysia where extrinsic reasons such as salary or job security, are even more influential when choosing a career in teaching than intrinsic or altruistic ones (Heinz ,2015). These findings were supported by Frusher and Newton (1987), who listed extrinsic reasons as the most influential aspects of the teaching career. In the current study, intrinsic, extrinsic and altruistic motivations are explored in teachers and compared to the students’ motivations in the previous study (Saks et al., 2016).

Teachers’ job satisfaction

Student perceptions of the teaching profession and teacher job satisfaction, how they reflect on their job and their attitudes towards their job are closely connected (Egwu, 2015). The way teachers feel about and perceive their role and how they behave in this role, is reflected in their interactions with students which in turn, affects student attitudes towards the profession and their readiness to pursue a teaching career.

Job satisfaction carries the individual’s personal message on the job he or she is doing. According to Locke (1976), job satisfaction is conceptualized as a pleasurable or positive emotional state which results from the appraisal of one’s job. These are a teacher’s affective reactions to his work and his teaching role. Pleased and satisfied teachers reflect a positive attitude towards their job. It has been claimed that job satisfaction among teachers depends on several factors – interactions with students, parents and colleagues, or teaching episodes (Skaalvik & Skaalvik, 2011). According to Johnson et al. (2012), the antecedents of job satisfaction include also workplace conditions, teacher autonomy, administrative support and staff collegiality. While specifying the work conditions, it is interesting that it is not physical conditions like clean classrooms or access to modern technology that mostly guarantees job satisfaction but rather social conditions like school atmosphere, relations between people, organizational culture and leadership.

Teacher job satisfaction is important not only for teachers but also for students and the whole school. It has been shown that it helps to create a positive academic atmosphere at school and supports student academic growth and progress (Johnson et al., 2012). Furthermore, it presents the image of a pleased teacher and a positive attitude about the teaching profession.

Problem Statement

In Estonia, similar traits can be identified in public attitudes towards teachers compared to other European countries. While generally, the reputation of teachers is on the rise in society (Johnson & Duffett, 2003; Rustique-Forrester & Haselkorn, 2002; Õpetajaameti kuvand ja atraktiivsus, 2016), the teachers themselves (Adams, 2003; Fuller et al., 2013; Õpetajaameti kuvand ja atraktiivsus, 2016; TALIS, 2014) as well as students (Saks et al., 2016) are significantly more critical and pessimistic. Teachers tend to underestimate public respect for their profession (Everton et al., 2007; Õpetajaameti kuvand ja atraktiivsus, 2016) and reflect this mentality to their students. This leads us to the problem that the low reputation of the teaching profession carried by teachers and public opinion, and reflected to the students does not attract them to pursue a career in teaching.

Research Questions

The research questions we are seeking answers to are as follows:

- How do teachers perceive their role at school and in society, and their relations with students, their parents and colleagues?

- Which type of motivation caused teachers to choose a career in teaching and how does this compare to the type that students preferred (Saks et al., 2016)?

- What do teachers think about the reluctance their students display towards pursuing a career in teaching, and what could be done to make the profession more attractive to them?

- Why should teachers encourage students to pursue a career in teaching, and how can they do that?

Purpose of the Study

The current research aims to investigate teachers’ attitudes towards the teaching profession and their role of promoting teaching as a career to their students.

Research Methods

This study of teachers’ perceptions of their profession was conducted as a follow-up to a study of student perceptions of the teaching profession (Saks et al., 2016). The sample for both studies, students and teachers were from the same schools. Data were collected from students and teachers in two following years. As the first study focusing on student perceptions of the teaching profession and their possible interest in pursuing a teaching career unexpectedly revealed a negative attitude and low interest in the teaching profession, it was necessary to explore possible causes of this outcome. Therefore, it was necessary to investigate which messages about the teaching profession students received from the primary source – their teachers.

Participants

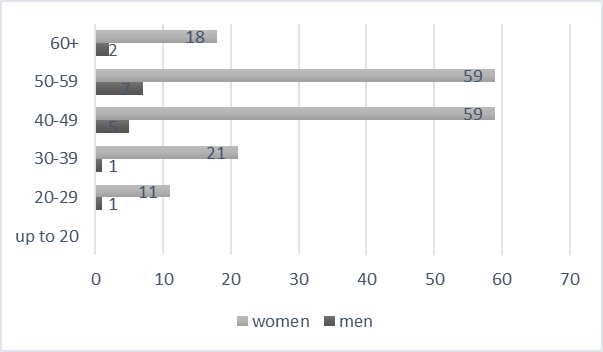

The sample was made of 580 teachers of 13 schools in a medium-sized town in Estonia. The invitation to participate in the study was sent to all teachers. The number of respondents who completed the electronic survey was 226 (39% of the entire teacher population). The average age of the respondents was 48 years (which is also the average age of Estonian teachers) (SD=9.9). According to gender (Figure 2) the sample was divided as follows: 7% of the respondents were men, 74% women and 19% did not answer the question on their gender and/or age.

The teachers participating in the study were rather equally distributed between the four school levels: level 1 (students aged 7–9 yrs) 20%, level 2 (10–12 yrs) 30%, level 3 (13–16 yrs) 31%, and level 4 (17–19 yrs) 17%.

Data collection and analysis

The data were collected from the respondents using an electronic survey (LimeSurvey) over a two-week period. After the first week, a reminder to complete the questionnaire was sent to the teachers. The results were analysed using the program SPSS 24, textual answers were coded, categorized and analysed using inductive content analysis.

Findings

RQ1 – How do teachers perceive their role at school and in society, and their relations with students, their parents and colleagues?

Teachers were asked whether they felt they were a role model for their students and colleagues, and whether they valued themselves as teachers, and whether they thought society valued them as teachers. The results showed that while in the first three cases the teachers were rather positive (83–96% of the responses were positive), in the last case only 61% of the teachers believed that they are valued in the community. This result is in line with earlier studies that claim teachers are rather negative about being valued by other people in society (Õpetajaameti kuvand ja atraktiivsus, 2016; TALIS, 2014).

Teachers also estimated the quality of relations with colleagues, students and their parents and the majority of the teachers admitted their relations were good or very good, especially with colleagues and students (93% and 97% respectively). The estimates about relations with parents were slightly lower, albeit not significantly lower (87%).

In order to explore the relationship between teachers’ perceptions of being a role model and their self-reported relations at school, a correlation analysis was applied. The analysis revealed significant positive albeit weak correlations between teacher perceptions of being a role model for students and their relations with students (r=.211, n=226, p<.001), their relations with parents (r=.237, n=226, p<.000), and colleagues (r=138, n=226, p<.040). The teachers who reported being a role model for their colleagues also have positive relations with them (r=.300, n=226, p<.000), as well as with students (r=.235, n=226, p<.000), and their parents (r=.217, n=226, p<.001).

What is interesting in the results of the correlation analysis is that the teachers who value themselves as teachers higher, do not report good relations with their colleagues, students or their parents. However, they consider themselves a role model for their students (r=.338, n=226, p<.000), and their colleagues (r=248, n=226, p<.000). Furthermore, the teachers who value themselves as teachers believe that society also values them, although the correlation coefficient is positive, it is nevertheless rather weak: r=.179, n=226, p<.007. It is also worth mentioning that the teachers who believe that society values them and their job, also have good relations with their colleagues (r=.217, n=226, p<.001), students (r=.196, n=226, p<.003), and their parents (r=.197, n=226, p<.003), but they do not think they serve as a role model for their students.

The results of the correlation analysis were as expected. The teachers who perceive themselves as being a role model for their students and colleagues, usually have good relations with them. What was somewhat unexpected was the correlation between how teachers value themselves and how they think society values them. Even though these two variables are positively correlated (r=.179, n=226, p<.007), the findings revealed that the teachers who value themselves as teachers, believe they are a role model for their students and colleagues. But the teachers who believe that society values them as teachers, report good relations with their colleagues, students and their parents. This is quite a different result to that of previous research. The possible explanations will be discussed below.

RQ2 – Which type of motivation caused teachers to choose a career in teaching and how does this compare to the type that students preferred?

In order to investigate what motivates teachers, they were asked what made them happy and unhappy in their job that day. Almost half of the teachers (46%) admitted that working with young people is the most rewarding thing in their job –The other factors – student progress (mentioned by 16% of teachers), diversity of the work (13%), and self-development (8%) were mentioned less frequently.

In reference to the most distressing factors in their job, undermotivated students was mentioned in 27% of cases). This was followed by low salary (15%), lack of creativity in their work (13%) and disrespectful attitude towards teachers, also the school system and management, both with 12%

In brief, teachers today enjoy the diverse work they can do with young people, and seeing them make progress. On the other hand, they are not satisfied with the situation where they have to invest a lot of time in work which is not valued by the students or their parents (and often by the school management), and which is underpaid.

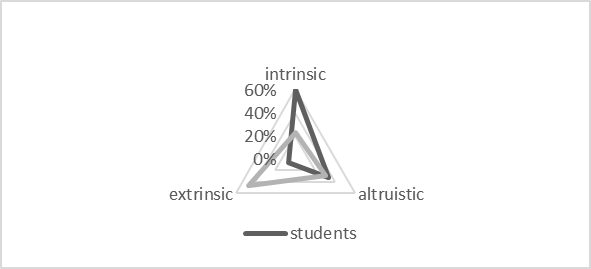

The responses from the teachers about what motivates them to work as teachers were divided into three categories: intrinsic, extrinsic and altruistic. The most frequently expressed motivations were extrinsic (47%):Altruistic motivation was evident in 30% of the responses), while intrinsic motivation was the lowest at 23%. These findings were compared to the responses of secondary students from the same schools collected a year earlier (Saks et al., 2016). The question posed to the students was – The analysis revealed a significant difference between what motivates the teachers and students (Figure 3). The intrinsic motivation appeared for 60% of the students, but only 23% of the teachers. The extrinsic motivation prevailed for 7% of the students, but 47% of the teachers. The altruistic motivation was more or less equal – 33% of the students and 30% of the teachers.

When interpreting these results, it could be assumed that the strong tendency for intrinsic motivation among the students is a good baseline for choosing a career in teaching. However, it does not seem to be the case when we consider the numbers entering teacher training programmes.

RQ3 – What do teachers think about the reluctance their students display towards pursuing a career in teaching, and what could be done to make the profession more attractive to them?

When teachers were asked why they thought young people do not want to pursue a career in teaching, 38% of the respondents pointed to the low salary as the most deterring factor. Almost a quarter of the teachers mentioned the stress and responsibility involved in the job but also the poor reputation the job has in society (17%). It is also remarkable that 5% of the teachers admitted that the teachers themselves are not positive role models for their students to follow. Even though the percentage of this answer is not high, it shows that teachers understand that their own image and attitude may not send a positive message about the job.

The most important changes the teachers recommended in order to make the teaching career more attractive to young people were mostly connected with external factors – increasing salary, the profession being valued by society, positive reputation and reducing the workload. In many cases the teachers highlighted the fact that their reputation in society is low. They also found that this reputation should be improved by someone else – society, policy makers etc. Only a few teachers understood their own role when influencing students attitude –

RQ4 – Why should teachers encourage students to pursue a career in teaching, and how can they do that?

When estimating the positive sides of the job to encourage students to pursue a career in teaching, over a quarter of the respondents mentioned the lack of routine (”). The other advantages highlighted were the sense of mission while doing the job (”) and constant self-development. It is interesting to note that 11% of the teachers admitted that they would not encourage youngsters to become teachers. Unfortunately, this answer was not commented upon any further; therefore, it is difficult to explain or give any reasons for such an answer.

As teachers play a great role in affecting student opinion and forming the mind-set in their profession, we investigated what teachers thought they could do to encourage students to pursue a career in teaching. While 40% of the teachers admitted that they could be a positive role model for their students), 11% of the teachers thought they could not do anything (). The other measures teachers suggested were teaching in an interesting way, having good relationships and being optimistic.

Conclusion

The current research was triggered by the results of a previous study, which explored perceptions of and attitudes to teaching profession among secondary students (Saks et al., 2016). As this study revealed rather negative perceptions of teaching profession, we set out to conduct a follow-up study to shed light on teachers’ self-concept and attitudes towards teaching profession by investigating how teachers felt about their job, their level of job satisfaction and what they could do to help popularize the profession. Gaining an understanding of why teachers perceive their job as they do, their level of job satisfaction and messages they send about their job to students help us understand student perceptions of teaching and find ways to popularize the profession.

Despite the fact that teachers believe they are role models for students as well as for colleagues as in several earlier studies (e.g. Ingersoll, 2001; Õpetajaameti kuvand ja atraktiivsus, 2016; TALIS, 2014), they seem to be more critical about the mind-set in their profession. Teachers tend to believe that they are not valued by society even though they do value themselves as teachers. However, according to the results of the study titled, (Õpetajaameti kuvand ja atraktiivsus, 2016), the reputation of teaching was estimated to be good or satisfactory by different stakeholders, while the teachers themselves and senior secondary students were the most critical. A similar observation was made by Hargreaves et al. (2006) when they showed that teachers estimated the status and esteem afforded by their colleagues and parents more highly than public opinion. A relatively negative public opinion is also the reason why many teachers do not recommend their students pursue a career in teaching. In the Estonian case, the cautious attitude to public opinion among teachers may be caused by the rather frequent public criticism in the media which does not always reflect teachers and their job in the most positive way. The media, as it is known, may have a lot of power to form public opinion as well as teachers’ opinion of the attitudes of the general public.

The data analysis revealed unsurprising correlations concerning the teachers’ perception of themselves as a role model and their reported relations with students and colleagues. Proceeding from the perspective of socio-analytic personality theory (Hogan, 1996), these two are connected with a person’s agreeableness, interest in being accepted and good reputation. The current research also revealed positive albeit weak correlations between the two, indicating that teachers who perceive themselves as being a role model for their students and colleagues, also practise good relations with them. Similar correlations appeared between the teachers’ perception of being valued by society and their relations with colleagues, students and their parents. Good relations with students and colleagues are expected prerequisites of job satisfaction (Skaalvik & Skaalvik, 2011), and give reason to believe that teachers are also able to create a friendly and supportive academic atmosphere at school.

The strongest motivations reported by the teachers in the current research were extrinsic. The most frequently named factors were connected with people: working with students is pleasurable, it is rewarding seeing student progress, and good, supportive colleagues create a pleasant working atmosphere. Another positive factor named by the teachers was the opportunity for self-development. These findings are not in line with the results of Page and Page (1981), who identified ‘contribution to humanity’ as the most encouraging factor in a teacher’s job, or Everton et al. (2007), who listed influencing children and their development as the most positive aspect of the teaching profession. The significant incline towards extrinsic motivation may be indicative of teachers’ attitudes towards their job. Teaching has always been considered a job with a mission that should be carried by an altruistic attitude. But if the altruistic is dominated by the extrinsic, this may devalue the role of the teacher as the keeper of the mission, and may later be reflected in public opinion.

The most discouraging factors revealed in the current study were associated with external aspects like low salary (mentioned several times by teachers as well as students), disrespect for teachers, unsupportive school system and management, lack of parental interest, and insufficient esteem from society. But teachers also mentioned school-related aspects like undermotivated students, few possibilities for creativity, stressful and responsible job and problems with discipline. Similar discouraging factors were found by Page and Page (1981), in addition to class control, salary, workload, status of teaching, high level of responsibility, and lack of discipline or authority (Everton et al., 2007).

Some interesting distinctions became evident when the study of the students’ motivations were compared with those of the teachers (Saks et al., 2016). The students have good motivational assumptions about the teaching career as they seem to emphasize internal and altruistic motivations. The reason they do not end up pursuing a teaching career may, on the one hand, be down to the teachers, who do not always encourage the students to choose the job, or on the other hand, the media and public opinion which views teaching as an underpaid profession, and does not always present teachers and teaching in the most favourable way.

There are several factors that affect professional reputation. The changes that teachers consider most necessary for improving the reputation of teachers and making the profession more attractive to students, are raising teacher’s salaries and affording teachers greater esteem in society, as well as reducing their workload and giving more rights to teachers. At the same time, teachers admit that their own attitude towards their job should be more positive and encouraging. They should consciously act as a positive role model, they should enjoy their work, express positive thoughts about their work and show job satisfaction. Therefore, teachers are well aware that they hold the key to the positive image of their job. However, far too often they seem to be preoccupied with their everyday work and problems, and hence do not pay enough attention to forming the image of their profession.

Considering the current study, not many serious limitations can be named. The sample used in the study was closely connected with the sample in the previous study (Saks et al., 2016). To be more exact, the teachers questioned in this study were the teachers of the students questioned a year before. Therefore, it can be claimed that the students expressed thoughts and feelings closely connected with the impressions made by the same teachers. One limitation that can be identified is connected with the measurement instrument, which was compiled by the authors and has not been used or validated with a wider sample. Therefore, it is difficult to have any cross-cultural comparisons based on this instrument.

In Estonia, the problem of teacher reputation and the sustainability of the teaching profession has become everyone’s problem. Proof can be seen in the updating of the teacher training curriculum and numerous initiatives to highlight teachers and their good work. October is celebrated as Teachers’ Month, World Teachers’ Day is celebrated at the beginning of October. Special events are held to express gratitude to teachers and reward the best of them. Several honorary titles are assigned to teachers including Teacher of the Year, Estonia Appreciates etc. Having public support, common respect and appreciation will hopefully cause the reputation of teachers to recover, self-esteem among teachers to improve and interest in the teaching profession to grow.

References

Adams, C. (2003). Third of teachers plan to quit. Report on keynote address to North of England Conference. http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/education/2633099.stm

Addison, R., & Brundett, M. (2008). Motivation and demotivation of teachers in primary schools: the challenge of change. Education, 36(1), 79–94.

Aksu, M., Demir, C. E., Daloglu, A., Yildirim, S., & Kiraz, E. (2010). Who are the future teachers in Turkey? Characteristics of entering student teachers. International Journal of Educational Development, 30(1), 91–101. DOI:

Bergmark, U., Lundström, S., Manderstedt, L., & Palo, A. (2018). Why become a teacher? Student Teachers’ Perceptions of the Teaching Profession and Motives for Career Choice. European Journal of Teacher Education, 41(3), 266–281.

Charalambos, A. (2017). Choosing the Teaching Profession: Teachers' Perceptions and Factors Influencing Their Choice to Join Teaching as Profession. Journal of Education and Practice, 8(10), 219–233.

Cheung, A. C., & Yuen, T. W. (2016). Examining the motives and the future career intentions of mainland Chinese pre-service teachers in Hong Kong. Higher Education, 71(2), 209–229. DOI:

Chong, S., & Low, E.-L. (2009). Why I want to teach and how I feel about teachingdformation of teacher identity from pre-service to the beginning teacher phase. Educational Research for Policy and Practice, 8(1), 59–72. DOI:

Cunningham, P. (1992). Teachers’ Professional Image and the Press, 1950–1990, History of Education, 21(1), 37–56.

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1985). Intrinsic motivation and self-determination in human behavior. Plenum.

Egwu, S. O. (2015). Attitude of Students towards Teaching Profession in Nigeria: Implications for Education Development. Journal of Education and Practice, 6(29), 21–25.

Everton, T., Turner, P., Hargreaves, L., & Pell, T. (2007). Public Perceptions of the Teaching Profession. Research Papers in Education, 22(3), 247–265. DOI:

Flores, M. A., & Niklasson, L. (2014). Why do student teachers enrol for a teaching degree? A study of teacher recruitment in Portugal and Sweden. Journal of Education for Teaching, 40, 328–343.

Fray, L., & Gore, J. (2018). Why people choose teaching: A scoping review of empirical studies, 2007-2016. Teaching and Teacher Education, 75, 153–163.

Frusher, S., & Newton, T. (1987). Characteristics of students entering the teaching profession. In Oklahoma Educational Research Symposium (pp. 1-18). Northeast State University OK.

Fuller, C., Goodwyn, A., & Francis-Brophy, E. (2013). Advanced skills teachers: professional identity and status, Teachers and Teaching, 19(4), 463–474. DOI:

Hall, D., & Langton, B. (2006). The status of teachers. New Zealand Teachers Council and Ministry of Education.

Hargreaves, L., Cunningham, M., Everton, T., Hansen, A., Hopper, B., McIntyre, D., & Wilson, L. (2006). The status of teachers and the teaching profession: Views from inside and outside the profession. Research Report RR755: DfES.

Hayes, S. (1990). Students’ Reasons for Entering the Educational Profession. Northwestern Oklahoma State University.

Heinz, M. (2013). The next generation of teachers: An investigation of second-level student teachers’ backgrounds in the Republic of Ireland. Irish Educational Studies, 32, 139–156.

Heinz, M. (2015). Why Choose Teaching? An International Review of Empirical Studies Exploring Student Teachers’ Career Motivations and Levels of Commitment to Teaching. Educational Research and Evaluation, 21(3), 258–297. DOI:

Hogan, R. (1996). A socioanalytic perspective on the five-factor model. In J. S. Wiggins (Ed.), The five-factor model of personality: Theoretical perspectives (pp. 163–179). Guilford.

Hoyle, E. (2001). Teaching. Prestige, Status and Esteem. Educational Management and Administration, 29(2), 139–152.

Hutchinson, G. E., & Johnson, B. (1994). Teaching as a Career: Examining High School Students’ Perspectives. Action in Teacher Education, 15(4), 61–67.

Ingersoll, R. M. (2001). Teacher Turnover and Teacher Shortages: an Organizational Analysis, American Educational Research Journal, 38(3), 499–534.

Johnson, J., & Duffett, A. (2003). An assessment of survey data on attitudes about teaching – including the views of parents, administrators, teachers and the general public. Public Agenda. http://www.publicagenda.org/research/research_topic.cfm

Johnson, S. M., Kraft, M. A., & Papay, J. P. (2012). How context matters in high-need schools: the effects of teachers’ working conditions on their professional satisfaction and their students’ achievement. Teachers College Record, 114(10), 1–39.

Judge, T. A., & Bono, J. E. (2001). Relationship of Core Self-Evaluations Traits – Self-Esteem, Generalized Self-Efficacy, Locus of Control, and Emotional Stability – with Job Satisfaction and Job Performance: A Meta-Analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(1), 80–92.

Jungert, T., Alm, F., & Thornberg, R. (2014). Motives for becoming a teacher and their relations to academic engagement and dropout among student teachers. Journal of Education for Teaching, 40(2), 173–185. DOI:

Kidd, L., Brown, N., & Fitzallen, N. (2015). Beginning Teachers’ Perception of their Induction into the Teaching Profession. Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 40(3), 153–173.

Kohl, H. (1984). Growing minds: on becoming a teacher. Harper and Row.

Köning, J., & Rothland, M. (2012). Motivations for choosing a teaching career: Effects on general pedagogical knowledge during initial teacher education. Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education, 40, 289–315. DOI:

Locke, E. A. (1976). The nature and causes of job satisfaction. In M. Dunette (Ed.), Handbook of industrial and organizational psychology (pp. 1297–1349). Rand-McNally.

OECD (2014). Education Indicators in Focus. (2014). https://www.oecd.org/education/skills.../EDIF2014No.20(eng).pdf

Õpetajaameti kuvand ja atraktiivsus (2016). The Image and Attractiveness of the Teaching Profession 2016. Report. TNS Emor.

Osguthorpe, R., & Sanger, M. (2013). The moral nature of teacher candidate beliefs about the purposes of schooling and their reasons for choosing teaching as a career. Peabody Journal of Education, 88(2), 180–197. DOI:

Page, J. A., & Page, F. M. (1981). Pre-service and In-service Teachers’ Perceptions of the Teaching Profession. Georgian Southern College.

Ralph, A. M., & MacPhail, A. (2015). Pre-service teachers' entry onto a physical education teacher education programme, and associated interests and dispositions. European Physical Education Review, 21(1), 51–65. DOI:

Reeves, T. D., & Lowenhaupt, R. J. (2016). Teachers as leaders: Pre-service teachers' aspirations and motivations. Teaching and Teacher Education, 57, 176–187. DOI:

Republic of Estonia 100 (2018). Statistics of Estonia. Statistikaamet. https://www.stat.ee/valjaanne-2017_eesti-piirkondlik-areng-2017

Rustique-Forrester, E., & Haselkorn, H. (2002) Learning from the US. In M. Johnson and J. Hallgarten (Eds), From victims of change to agents of change: the future of the teaching profession (pp. 82–100). Institute for Public Policy Research.

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Intrinsic and extrinsic motivations: classic definitions and new directions. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 25, 54–67.

Saks, K., Soosaar, R., & Ilves, H. (2016). The Students’ Perceptions and Attitudes to Teaching Profession, the Case of Estonia. The European Proceedings of Social & Behavioural Sciences EpSBS, 470−481. DOI:

Skaalvik, E. M., & Skaalvik, S. (2011). Teacher job satisfaction and motivation to leave the teaching profession: Relations with school context, feeling of belonging, and emotional exhaustion. Teaching and Teacher Education, 27(6), 1029–1038. DOI:

Struyven, K., Jacobs, K., & Dochy, F. (2013). Why do they want to teach? The multiple reasons of different groups of students for undertaking teacher education. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 28(3), 1007–1022. DOI:

TALIS (2014). https://www.hm.ee/sites/default/files/talis2013_eesti_raport.pdf

Watt, H. M. G., Richardson, P.W., Klusmann, U., Kunter, M., Beyer, B., Trautwein, U., & Baumert, J. (2012). Motivations for choosing teaching as a career: An international comparison using the FITChoice scale. Teaching and Teacher Education, 28, 791–805. DOI:

Wong, A. K. Y., Tang, S. Y. F., & Cheng, M. M. H. (2014). Teaching motivations in Hong Kong: Who will choose teaching as a fallback career in a stringent job market? Teaching and Teacher Education, 41, 81–91. DOI:

Yüce, K., S¸ Ahin, E., Koçer, O., & Kana, F. (2013). Motivations for choosing teaching as a career: A perspective of pre-service teachers from a Turkish context. Asia Pacific Education Review, 14(3), 295–306. DOI:

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

24 November 2020

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-952-8

Publisher

European Publisher

Volume

1

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-370

Subjects

Education, educational psychology, pedagogy, positive pedagogy, special education, second language teaching

Cite this article as:

Saks, K., & Ilves, H. (2020). Teachers as Promoters of Teaching: Teachers’ Perceptions of Their Profession, The Case of Estonia. In P. Besedová, N. Heinrichová, & J. Ondráková (Eds.), ICEEPSY 2020: Education and Educational Psychology, vol 1. European Proceedings of International Conference on Education and Educational Psychology (pp. 141-153). European Publisher. https://doi.org/10.15405/epiceepsy.20111.13