Abstract

The general ageing of population is reflected at schools similarly to the society as a whole. The average age of teachers is growing and young people do not find the teaching career attractive enough to pursue. This is leading to the situation where the schools may lack teachers in 10-15 years’ time. The aim of the current study was to explore the 18-19-year-old students’ perceptions and attitudes to the teaching profession in the case of Estonia. 275 students were questioned to explore the popularity of the teaching profession. The results revealed that although the students value teachers’ job highly, they consider it a hard, underpaid and low-challenging job.

Keywords: Teaching professionstudentsperceptionsquestionnaire

Introduction

The rapidly ageing teaching workforce is considered problematic in many parts of the world (OECD, 2014). Similarly to many other countries, Estonia may be facing the shortage of teachers in ten-fifteen years’ time. Today, the teachers’ average age in Estonia is 48. Almost 30% of all teachers are in the age group of 50-59 years, and 16% are in the group of over 60 years whereas teachers under 30 years make only 7.5% of the whole teacher population (TALIS, 2013). According to the report of OECD (2014), Estonia is one of the two countries with the oldest and still ageing teacher population. The small number of young teachers in Estonian schools is caused by young people’s little interest in the teaching profession which in turn may be the result of low prestige of the profession in the society. This may lead to the situation where the large numbers of retiring teachers are difficult to replace with new recruits which may worsen teacher shortages even further (OECD, 2014). To prevent the complicated situation at schools and raise students’ interest in the teaching profession, a study was launched to explore students’ attitude towards the profession. Knowing students’ perceptions of the teaching profession enables to take measures for popularizing the profession among young people and encouraging them to pursue the teaching career. In this paper we focus on exploring the students’ perceptions of the teaching profession with the aim to find out which are their attitudes towards the job. The following subsection gives an overview of earlier studies on the topic. At the end of the section, the research questions are posed.

Theoretical framework

So far, many studies have explored student-teachers’ and teacher candidates’ career motivations and commitment (Heinz, 2015). There are much less studies concerning the students’ attitudes towards teaching career. However, these two aspects – students’ perceptions of the teaching profession and teachers’ reflections and attitudes towards their job are closely connected (Egwu, 2015). The way how teachers feel and perceive their role and how they behave in this role, is reflected in their interactions with students which in turn, affects the students’ attitudes towards the profession and their readiness to pursue the teaching career.

Young people who are starting their professional life, want to build up the career which is respected and valued. Public attitude has an important role in forming the occupational prestige (Hayes, 1990). Teachers’ reputation may differ greatly in different societies depending on their traditions, historic, cultural and religious background. Researchers from different countries have reported the decline of respect for teachers (Hammet, 2008; Scott et al, 2001; Sokolova, 2011). The main reason brought out is the inappropriately low rating of the teachers’ work expressed in pay level (Sokolova, 2011). According to Hammet (2008), younger generations assert their notion of respect through economic capital instead of cultural. Another reason for the declining respect is the status of teacher as an employee in the service sphere (Sokolova, 2001). Civic identities (including the respect with which teaching is regarded) are declining under the challenge of increasingly commercialised identities (Barber, 2001). In Estonia, the teaching profession is considered valuable but at the same time, undervalued (Õpetajaameti kuvand, 2016). According to the results of the study

Apart from reputation and public attitude, students’ motivation and interest in teaching play an important role when choosing a career. Most motivations why young people may or may not consider pursuing the teaching career can be distinguished as intrinsic, altruistic and extrinsic (Heinz, 2015). According to the Self-Determination Theory (Deci, & Ryan, 1985), intrinsic motivation refers to doing something because it is inherently interesting and enjoyable for the individual, whereas extrinsic motivation refers to doing something in order to attain a desired outcome, e.g reward (Ryan, & Deci, 2000).

Altruistic motivation is comprehended as something socially worthwhile and important enabling to contribute to the wellbeing of society and mankind (Heinz, 2015). The impulse to teach has been considered fundamentally altruistic as it represents an individual’s desire to share what he/she values and to empower other people (Kohl, 1984). Several studies suggest that the teaching career is attractive above all for those who desire intrinsic rewards and who approach teaching as a calling (Hayes, 1990). Earlier research (e.g Köning, & Rothland, 2012; Wong et al, 2014) has shown that intrinsic motivation has the biggest influence on decision-making in this domain. Interest in the subject matter and wish to give on their knowledge are the main intrinsic factors that urge youngsters to choose the teaching career (e.g Flores, & Niklasson, 2014; Hayes, 1990).

Extrinsic reasons, like status, pay and job security do not usually prevail as the main motivations for work compared to intrinsic and altruistic ones (e.g Hayes, 1990; Heinz, 2013; Watt et al, 2012). However, there are several exceptions like China, Turkey or Malaysia where extrinsic reasons such as salary or job security, are even more influential reasons for choosing the teaching career than intrinsic or altruistic ones (Heinz, 2015). These findings were supported by Frusher & Newton (1987) who listed extrinsic reasons (low salary, discipline problems and lack of classroom equipment) as the most influential aspects of teaching. Heinz, in his comparative analysis (2015), brought out several subdivisions for extrinsic motivations: the compatibility of the teaching profession with family responsibilities, teaching profession as a ―springboard‖, teaching profession as a ―fallback‖, influence of family members and socio-cultural influences.

Teachers are important role models to students. Their role has become even more important due to weakening family units and working parents (Stiegelbauer, 1992). The closer contacts people have, the bigger impact they have on each other. Therefore, it is crucial for teachers to observe how they reflect their feelings and satisfaction with their job, and which messages they forward to students about their job. This in turn, may influence students’ perceptions and interest in the teaching career. The current research aimed to explore the 18-19-year-old students’ perceptions of the teaching profession, and to find out their attitudes towards it. Proceeding from that we posed the following research questions:

How do students rate the teaching profession by its reputation in the society?

How do students perceive the positive and negative aspects of the teaching profession?

Which are the reasons why students consider/don’t consider the teaching profession? Does a teacher in the family have an impact on students’ consideration to become a teacher?

What kind of change would make students consider becoming a teacher?

Research methods

Participants

Data were collected from the final-grade students of 5 gymnasia of Pärnu (a middle-size town in Estonia). The data were collected from the students who were present at school on that day. 275 students participated in the survey (72% of all final-grade students). There were 129 boys (47%) and 146 girls (53%) in the final sample. The average age of the students was 18.1 (SD=0.41).

2.2 Data collection and analysis

In order to assess the popularity of the teaching profession among the gymnasium students a questionnaire was developed by the authors of the paper. The questionnaire consisted of 10 questions, which were mostly open-ended questions enabling the respondents to express their opinion. Two questions included rating the items on a scale.

After receiving the consent to participate in the survey from the administrations of the gymnasia, it was carried out in November – December 2013. The time of the survey was agreed on and fixed with the administrations. The paper versions of the questionnaire were delivered to the gymnasia at a fixed time. Students filled in the questionnaires in pencil. Filled questionnaires were collected after completion.

The collected data were analyzed in January 2014. To analyze the data mixed method was used, descriptive analysis, correlation analysis and t-tests for quantitative data, and thematic text analysis for open questions. Many students used a possibility to leave comments to the questions which are used below to illustrate their viewpoints. The survey was anonymous and the data were used in a generalized way, only for this specific study.

Results

The results of the research will be presented according to the research questions.

How do students rate the teaching profession by its reputation in the society?

To estimate how students rated the reputation of the teaching profession, they were asked to assess it on a scale of 1 to 5 [

Next, the students were given a list of twelve professions (Table

To be sure that the differences between the means of different professions were significant, the paired-samples t-test was conducted. The only statistically significant differences revealed between

The findings indicate that the reputation of the teaching profession is rather low as perceived by Estonian 18-year-old students outracing manicurist’s and shop assistant’s only. However, having close contacts with their teachers on a daily bases, students recognize good teachers and value them –

―Teacher’s job is extremely complicated and their contribution should be more valued and respected.‖ Another comment – ―More recognition and higher salary for the teachers, because teacher’s job is actually one of the most important ones‖ shows that students realize that the teaching profession should be more recognized and valued in the society.

How do students perceive the positive and negative aspects of the teaching profession?

To answer the second research question students were asked to put down three most positive things and three most negative things about the teaching profession that came to their mind. These were open questions and students were not guided or provided with options. The answers were coded and analyzed according to the topics.

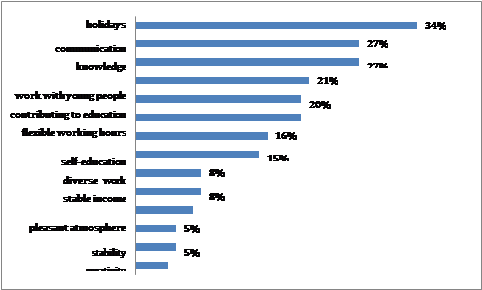

The most positive aspect that more than a third of the students brought out was long holidays (Figure

When listing the negative aspects of the teaching profession, students predominantly named external reasons (Figure

The students’ list of negative aspects reflects the everyday life and atmosphere at school that students daily perceive. However, it was interesting that students had noticed teachers’ big workload and admitted the presence of misbehaving and disrespectful peers – ―

Which are the reasons why students consider/don’t consider the teaching profession? Does a teacher in the family have an impact on students’ consideration to become a teacher?

The students were also asked whether they had ever considered becoming a teacher. Their answers were compared to the answers to another question – Does any of your family members or close relatives works/has worked as a teacher? The results indicated that 38% of the girls had considered becoming a teacher whereas the percentage for boys was only 19%. The ratio of students who had considered becoming a teacher was bigger in the case of students who had a teacher in their family compared to those who did not have a teacher in their family (Figure

Proceeding from this ratio, we checked whether the students’ interest in the teaching profession was correlated with having a teacher in the family. The Pearson correlation test revealed a significant positive correlation (r=.229, p<.000) indicating a weak correlation between the two measures. The possible explanations will be given below.

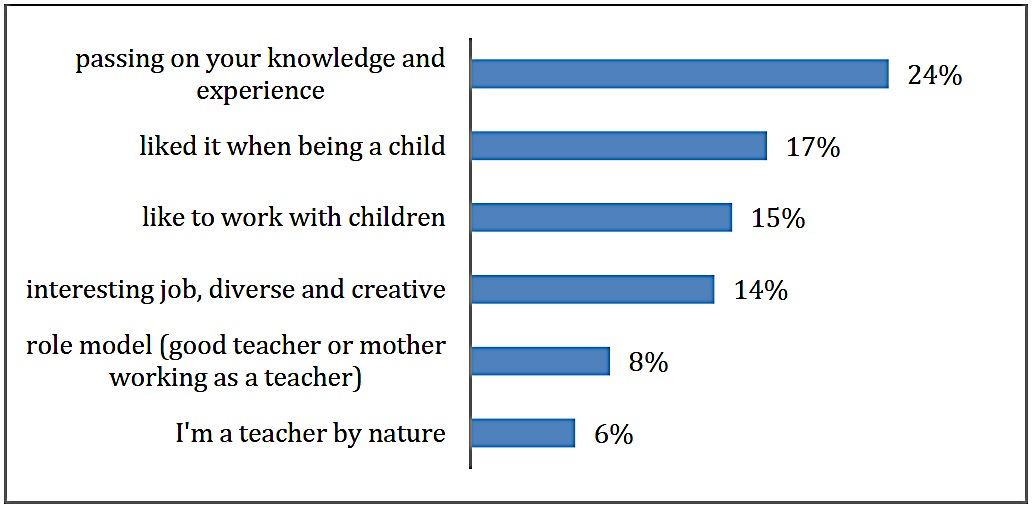

Next, the students’ motives to become a teacher were explored. Almost a quarter of the respondents, who had considered the teaching profession, named the possibility to pass on their knowledge and experience first (24%) (Figure

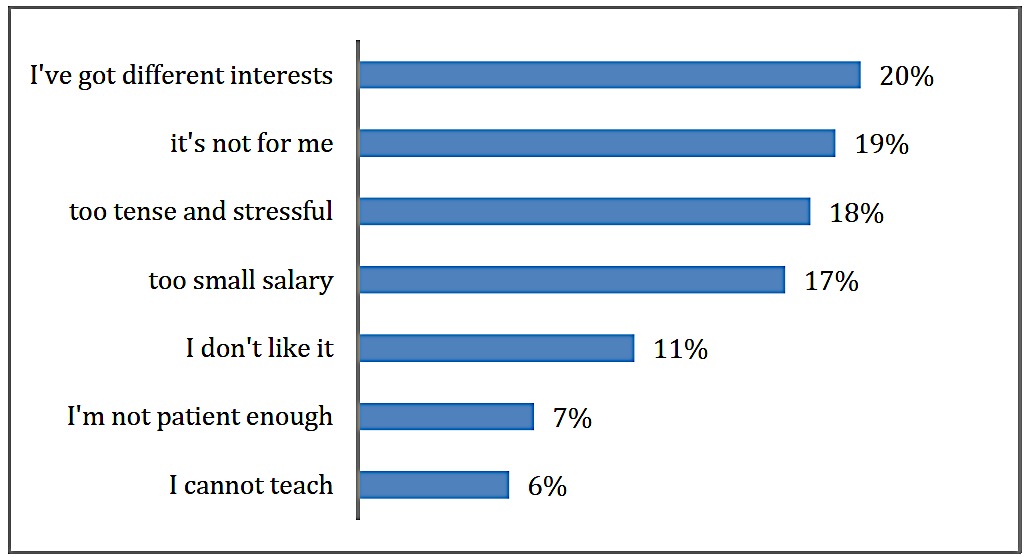

The students who did not think of the teaching profession as an option gave the following reasons (Figure

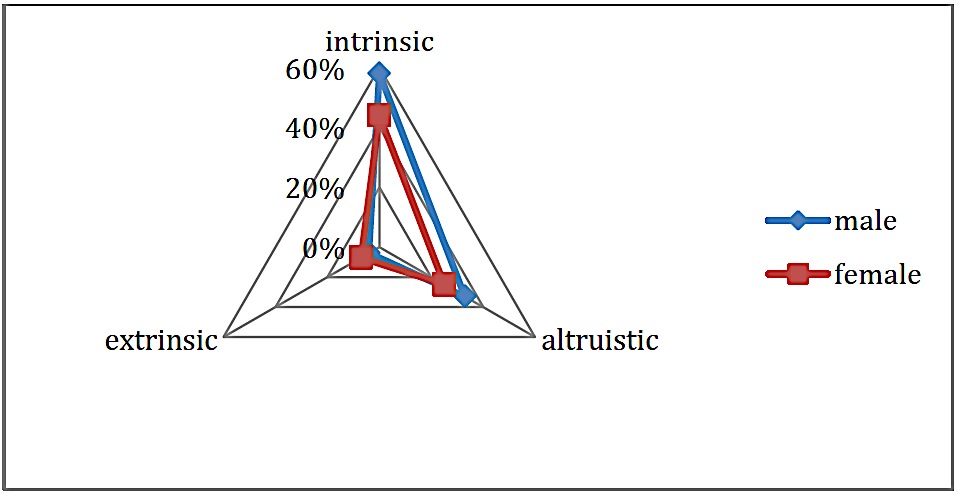

When boys’ and girls’ answers were compared considering their intrinsic, extrinsic and altruistic reasons separately, it appeared that boys slightly outperformed girls on intrinsic and altruistic scales, whereas girls’ answers revealed slightly more extrinsic motivations (Figure

A student’s comment – ―Some people are born to be teachers. Teaching involves much more than just passing on the knowledge. Teacher’s role in guiding the young person’s future is enormous.‖

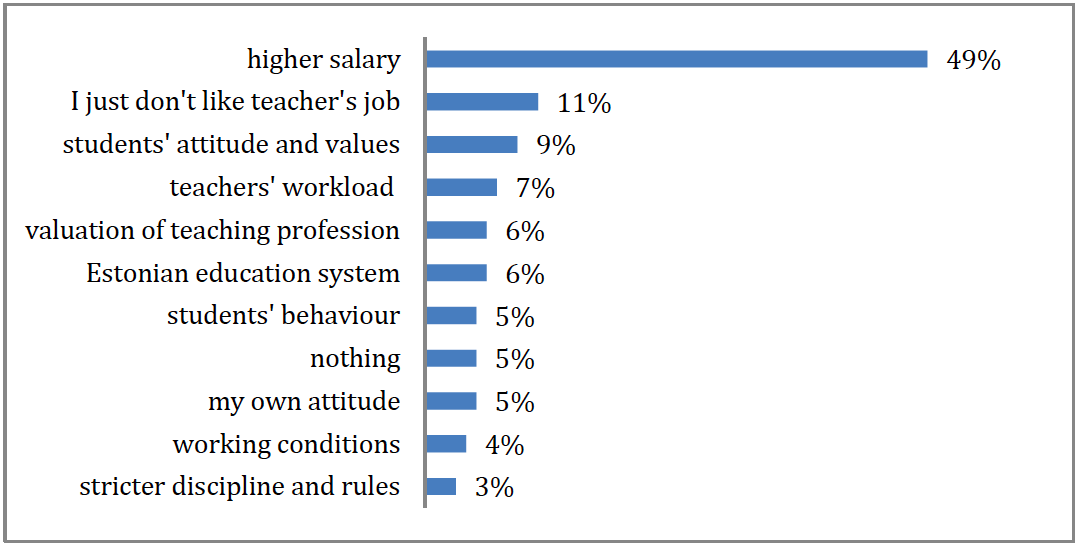

When students were asked about the measures which could make them consider the teaching profession, almost half of the respondents named rise in salary (Figure 7). All the other changes – students’ attitudes, teachers’ workload, valuation of the teaching profession etc – had a smaller proportion.

The changes that could make students consider the teaching profession.

However, 11% of the youngsters answering

4. Conclusion

In conclusion, it can be said that students seem to have a rather adequate understanding of teacher’s job, but realizing its difficulties and problems does not inspire many of them to follow this path and pursue the teaching career.

The positive factors that influenced students to consider the teaching profession – passing on knowledge and working with children – went in line with other altruistic reasons reported in earlier studies (e.g Frusher & Newton, 1987; Hayes, 1990; Horton & Summers, 1984; Stiegelbauer, 1992). Unlike earlier findings, altruistic as well as intrinsic motivations were slightly dominating in males’ responses.

Another distinctness which revealed in the current study was connected with positive role models in students’ families. While other researchers have not reported any relations between students’ interest in the teaching profession and having a teacher in their family (Frusher & Newton, 1987), the current findings indicated to a weak correlation between these measures. Having a role model as a teacher- family member creates the desire to resemble these people and contribute to the development of children in the similar way. Unlike several studies conducted in the US (Teaching as a career, 1985), the Estonian students admitted that positive experiences with their teachers at school as well as having teachers in their own families worked as a positive role model, which might encourage them to become a teacher. This finding leads to the recognition that the reflections and messages that teachers forward about their job when working with students are very important as they may influence students’ future career choice.

Students understand that the requirements set to teachers and the salary paid for their work are not in balance. These findings support Frusher & Newton (1987) and Book et al (1984) who found that concern about salary is a major factor in deciding whether or not to choose teaching as a career choice.

Similarly to the same authors (Book et al, 1984; Frusher & Newton, 1987; Teaching as a career, 1985), the students in the current study also referred to the increase in salary as the most important change to be made. Another reason which discourages students to consider the teaching profession is a big workload (similarly to Teaching as a career, 1985). Notably much attention was paid to the drawbacks in students’ behaviour and disrespect for teachers.

The study was limited by the absence of validity test of the questionnaire used for the study. However, the statements of the questionnaire were piloted with a small group of educational experts to check the unequivocality of the utterances. Another limitation lies in the fact that for some analyses the sample approved to be too small which did not enable to make generalisations for the differences between boys and girls.

As to the ideas for further research it could be investigated how many people from this cohort continued their studies in teacher training and whether any of them started their teaching career at school. Considering students’ low interest in the teaching profession and their low estimates of teachers’ reputation, it would also be interesting to investigate teachers’ perspective – how they feel as teachers, which messages they forward to their students about their profession, and how they reflect their well-being and satisfaction with their job.

References

- Barber, B.R., 2001. Blood brothers, consumers, or citizens? Three models of identity—ethnic, commercial and civic. In: Gould, C.C. & Pasquino, P. (Eds.), Cultural Identity and the Nation State. Rowman and Littlefield, Lanham, 57–65.

- Book, C., Freeman. D. & Brousseau, B. (1984). Comparing academic backgrounds and career aspirations of education and non-education majors (ReportNo. 2). East Lansing: College of Education, Michigan State University.

- Deci, E. L. & Ryan, R. M. (1985). Intrinsic motivation and self-determination in human behavior. New York: Plenum.

- Egwu, S. O. (2015). Attitude of students towards teaching profession in Nigeria: implications for education development. Journal of Education and Practice, 6(29), 21-25.

- Flores, M. A. & Niklasson, L. (2014). Why do student teachers enrol for a teaching degree? A study of teacher recruitment in Portugal and Sweden. Journal of Education for Teaching, 40, 328–343.

- Frusher, S. & Newton, T. (1987). Characteristics of students entering the teaching profession. Oklahoma Educational Research Symposium, Northeast State University OK, 1-18.

- Hammet, D. (2008). Disrespecting teacher: the decline in social standing of teachers in Cape Town, South Africa.

- International Journal of Educational Development, 28, 340-347.

- Hayes, S. (1990). Students’ Reasons for Entering the Educational Profession. Northwestern Oklahoma State University, Oklahoma.

- Heinz, M. (2013). The next generation of teachers: An investigation of second-level student teachers’ backgrounds in the Republic of Ireland. Irish Educational Studies, 32, 139–156.

- Heinz, M. (2015). Why choose teaching? An international review of empirical studies exploring student teachers’ career motivations and levels of commitment to teaching. Educational Research and Evaluation, 21(3), 258-297. doi:

- Horton, D. & Summers, J. (1984). A ten-year study on quantity, quality and personal characteristics of teacher candidates (Report No. 143). Indiana State University: Department of Secondary Education.

- Kohl, H. (1984). Growing minds: on becoming a teacher. New York: Harper and Row.

- Köning, J. & Rothland, M. (2012). Motivations for choosing a teaching career: Effects on general pedagogicalknowledge during initial teacher education. Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education, 40, 289–315. doi:

- OECD 2014. Education Indicators in Focus (2014). Retrieved from https://www.oecd.org/education/skills.../EDIF2014No.20(eng).pdf.

- Õpetajaameti kuvand ja atraktiivsus 2016. (2016). (The Image and Attractiveness of the Teaching Profession 2016). Report. TNS Emor.

- Ryan, R. M. & Deci, E. L. (2000). Intrinsic and extrinsic motivations: classic definitions and new directions.

- Contemporary Educational Psychology, 25, 54-67.

- Scott, C., Stone, B. & Dinham, S. (2001). ―I love teaching but…‖: international patterns of teacher discontent.

- Education Policy Analysis Archives, 9(28), 1-7.

- Sokolova, I. I. (2011). Pedagogical education. Current challenges. Russian Education and Society, 53(10), 80- 89.

- Stiegelbauer, S. (1992). Why We Want To Be Teachers: New Teachers Talk about Their Reasons for Entering the Profession. Annual Meeting of the American Educational Research Association, San Francisco, CA.

- TALIS 2013. Rahvusvaheline vaade õpetamisele ja õppimisele (TALIS report in Estonian). (2014). Retrieved from https://htm.ee/sites/default/files/talis2013_eesti_raport.pdf.

- Teaching as a career. High school students’ perceptions of teachers and teaching (1985). Education Standards Commission, Florida State Dept. of Education, Tallahassee.

- Watt, H. M. G., Richardson, P.W., Klusmann, U., Kunter, M., Beyer, B., Trautwein, U., & Baumert, J. (2012). Motivations for choosing teaching as a career: An international comparison using the FITChoice scale. Teaching and Teacher Education, 28, 791–805. doi:

- Wong, A. K. Y., Tang, S. Y. F. & Cheng, M. M. H. (2014). Teaching motivations in Hong Kong: Who will choose teaching as a fallback career in a stringent job market? Teaching and Teacher Education, 41, 81–91. doi:

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

22 November 2016

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-015-0

Publisher

Future Academy

Volume

16

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-919

Subjects

Education, educational psychology, counselling psychology

Cite this article as:

Saks, K., Soosaar, R., & Ilves, H. (2016). The Students’ Perceptions and Attitudes to Teaching Profession, the Case of Estonia. In Z. Bekirogullari, M. Y. Minas, & R. X. Thambusamy (Eds.), ICEEPSY 2016: Education and Educational Psychology, vol 16. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 470-481). Future Academy. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2016.11.48