Abstract

A plethora of studies have been undertaken on retirement, but the topic of women’s retirement has rarely been studied. According to reports, women live longer than men so they should be well prepared for life after retirement. Concerns have also been raised about the substantial difference between the quality of life in urban and rural communities. Undoubtedly, retired women in urban regions have more financial needs and a higher level of consumption. Thus, the overarching goal of this research is to convey a more holistic view of the issues by establishing a way to represent the theoretical basis of financial security indicators. The Klang Valley served as the study's focal point. Literature analysis was performed to find indicators for modelling the financial security of retired women based on publications related to retirement issues and the determinate indicators. In the subsequent phase, the model was validated through focus group discussions (FGD), interviews with experts and a pilot study. The data was analysed using partial least square structural equation modelling (PLS-SEM). Thus, in the first stage of this ongoing study, the authors proposed four essential contributors to the women’s financial security model: capacity, opportunity, willingness, and biopsychosocial factors (COWB). The COWB model was hypothesised to have a substantial link to the financial well-being of retired women.

Keywords: Capacity, opportunity, willingness, biopsychosocial, retirement

Introduction

According to Feldman (1994), retirees are middle-aged persons who leave their jobs or careers of many years to reduce the psychological commitment of continuing to work. Retirement planning is a dynamic and ongoing lifelong process (Chan et al., 2021) that requires adjustments as circumstances change (Wang & Wanberg, 2017). Many Malaysians in their prime working years worry about their post-retirement period and how they will be able to survive once they reach Malaysia's mandatory retirement age of 60. Many of them need to continue working in retirement to pay for necessities like food and healthcare because they have low levels of personal savings. The rapid ageing of the Malaysian population makes it more crucial than ever for people to prepare financially for retirement (Tai & Sapuan, 2018).

According to the most recent data from the Department of Statistics Malaysia (DOSM) (2020), the number of people living to the age of 60 has increased, and, interestingly, women are expected to live longer. According to their estimation, the average woman’s lifespan is projected to be 81.2 years, while the average man’s lifespan is projected to be 78.6 years. The annual percentage of the workforce in or above their sixties has also been growing steadily. According to projections for 2020, the number of people aged 60 and above was expected to rise from 3.4 million in 2019 to 3.5 million, representing 10.5% of the total population. However, these concerns are more climacteric for women because of the unique challenges they experience in the ageing environment. This means that women of all ages need to prepare financially for a longer retirement period. This problem is being exacerbated by the insufficient incomes of a growing proportion of the elderly population, which must meet its basic needs once they retire (Selvadurai et al., 2018). The elderly and their healthcare costs are at risk due to ageing; this places a strain on fiscal and private expenditure. It would be beneficial to address the concerns related to longer post-retirement life issues, particularly the financial problems associated with the longevity of this ageing population (Fen, 2018). As a consequence, this segment of society will encounter more pressing financial needs in the future and will have to save more money (Arham et al., 2019)

Literature Review

Retirement issues are becoming more critical for women due to the unique challenges of women's retirement. Aside from the issues of longevity, they also face gender pay gap disputes, especially with the wage gap and income gap differences that could contribute to the state of their financial well-being. For example, in Malaysia, for every RM100 income earned by men, women only received RM98.80 in 2018 (DOSM, 2018). According to the World Economic Forum (2020), a 40% wage gap ratio (women's wages to men's wages for the same position) still exists, as does an income gap of over 50% (women's total wage and non-wage income of men). According to the same report, women face considerable barriers when evaluating loan opportunities or financial goods, making it difficult for them to create businesses or earn an income through asset management.

Furthermore, financial capability appears to differ significantly between the genders (Sabri et al., 2020). Women are stereotyped as being less financially literate, less self-assured, and more reliant on the advice of others when making investing decisions (Mathew et al., 2020). The issue of Malaysian women’s lack of confidence was reported by Juen and Sabri (2012). Their research revealed that retirement confidence was found to be significantly associated with factors such as marital status, level of education, income, savings motivation, financial literacy, and financial management practices among government-employed women.

By contrast, Sharma and Kota (2019) found that most women lacked confidence in equity investing due to the riskiness of the financial investment, this further contributes to the fact that most women do not understand the benefits of investing in mutual funds. Women have always had insufficient savings which has contributed to their low levels of lifetime income. This might be because they are unlikely to have additional income available for supplementary contributions to retirement savings while in the labour force. However, women also plan less frequently for retirement than men, with the study by Farrar et al. (2019) confirming a lack of planning among women. Thus, women’s retirement planning is becoming an issue that needs further clarification, given that women have a more difficult path to financial wellness. Consequently, the poverty rate among women is higher and depend on social security to meet their needs during their retirement (Lyons et al., 2018).

Financial securities and the COWB model

Growing evidence indicates that monetary strains and stresses have a major influence on psychological well-being (Asebedo & Wilmarth, 2017; Marshall et al., 2021). Thus, prioritising money making and financial security yields further important benefits such as the ability to live securely when retired. However, the financial security concept is relatively new in Malaysia (Ahmad et al., 2017). Arguably, numerous aspects are related to and affect financial security. These include such things as monetary strains, mechanisms for self-coping, financial competency and practices concerning the use of money. Financial security can be defined as a situation in which one’s income or alternative resources are reliable enough for certain living standards to be maintained at present and in the future. Some key features of financial security are that ongoing solvency is likely to continue, the individual has an expectation of their cash flow in the future, and employees are secure in their job roles (Ahmad & Sabri, 2014). Additionally, a person’s financial condition refers to the feeling of having enough money to support their present life, and expected ways of living in the future, including financial independence (Brüggen et al., 2017). According to academic observations, financial security is often associated with the amount of money saved, the individual’s capacity to address emergency situations, a satisfactory level of monetary resources once retired, and accessible income (Haines et al., 2009; Lange et al., 2012; Mahal et al., 2012).

In this study, the retirement situation of women was assessed using the COWB model, which defines an array of financial securities that serve as determinants. To hypothesise the retirement security framework for women in the Klang Valley, the researchers employed the Capacity-Opportunity-Willingness-Biopsychosocial (COWB) framework. While some models focus solely on the financial components of retirement planning (Hershey et al., 2007, 2013), this paper’s suggested model discusses these elements in combination with those in four other contexts, therefore making it more comprehensive. This research integrated one new indicator, Biopsychosocial, as a predecessor to create a more holistic model with which to investigate the financial security of women in retirement and building on the work of Hershey et al. (2013), who developed the Capacity-Willingness-Opportunity Model.

Capacity

As outlined by Bagozzi and Dholakia (1999), capacity is an individual’s skill to finalize a choice and the degree of certainty required, which includes the individual’s knowledge level, their specialised level, and the material resources predicted to assemble one’s decision making. In this research, capacity is related to a proposal by Hershey et al. (2013), which can be characterised as the individual’s capacity to plan and save for retirement and which separates different outcomes for different individuals. Capacity has been viewed as a complicated component that consolidates various elements like mindfulness, information, experience, proficiency, abilities, openness to information and monetary resources (Bahaire & Elliott-White 1999).

Initiating the processes of knowledge creation, dissemination and assimilation requires the involvement of every single person, making individual-level variables a necessary precondition for these capacities (Yildiz et al., 2019). Yet research has demonstrated that in terms of financial literacy and behaviour, financial security applies less to women than it does to men. The results of previous research by Rai et al. (2019), who examined financial education among women, revealed that financial knowledge has weaker links with financial education than financial attitude or behaviour. According to the findings of Mukong et al. (2020), financial literacy makes a significant and positive contribution to bridging the gender-based financial inclusion disparity. An increase in women's financial inclusion requires a corresponding rise in women's financial literacy. This entails women having access to previously unavailable financial opportunities and services, which could contribute, not only to their own well-being, but also to the economic and social progress of the nation as a whole (D'Silva et al., 2012). As a result, women's long-term financial security is more likely to be assured if they are financially self-sufficient; this may be achieved by increasing their financial literacy (Roy & Patro 2022).

Opportunity

The Opportunity Model (Hershey et al., 2013) refers to the favourable situations that a person chooses in a specified timeframe (Yildiz et al., 2019). According to the authors, different opportunities may be represented by a range of circumstances, which could lead to a variation in the likelihood that similar behaviours will occur. When an individual engages in planning for their retirement, the key aspect of deciding and choosing investments is determining the range of opportunities that members can access (Olsen & Whitman, 2007). Consequently, the absence of satisfactory financial planning for retirement adversely influences retired people who need adequate resources in this last phase of their life (Sartori et al., 2016). In a surprising finding, nearly 90% of households in Malaysia have no savings for emergencies and, in fact, are facing situations of substantial debt (Ngui, 2016; Shukri, 2014). A major issue to address is the growing population of those likely to live for many years once they retire (World Health Organization, 2018). The experience of retired life can be complicated and challenging, so the promotion of retirees' well-being should be undertaken (França & Hershey, 2018; Yeung & Zhou, 2017).

As a consequence of the changing retirement income scenario, in 2018, the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) encouraged public and private retirement associations to start programs that would advance the retirement saving funds of pre-retirees. The OECD urged individuals to save more and focus continuously on arranging retirement planning for their future which would simultaneously help consumers to make appropriate choices by giving them opportunities. It was also suggested that pension providers give adequate knowledge exposure to all pre-retired employees, thus opening up significant investment opportunities (OECD, 2018). Thus, retirement saving funds are becoming exceptionally important among Malaysian adults as a component of lifelong financial planning (Nga, 2018).

Willingness

Willingness, as developed by Hershey et al. (2013), comprises the motivational factors that encourage financial preparation and savings. This indicator includes the motivational forces, attitudes and behavioural elements that determine the likelihood that a person will start planning and exert periodic effort to maintain this action (Topa et al., 2018). One aspect of willingness that has been extensively investigated is risk tolerance. In general, the results of empirical studies are consistent in finding that when women make financial decisions, their risk tolerance is lower than that of men (Byrnes et al., 1999; Gibson et al., 2013; Grable & Lytton, 2001; Hawley & Fujii, 1993; Jianakoplos & Bernasek, 1998; Olsen & Cox, 2001). Most agree that risk tolerance is higher in males than it is in females (Dickason & Ferreira, 2018). Gender variations in risk preferences may cause disparities in portfolio distributions, leading to unequal distribution of wealth (Yao et al., 2011). For instance, since she is likely to have a longer lifespan, a woman who has a lower risk tolerance level might not have undertaken sufficient preparation for when she retires. According to Robb and Woodyard (2011), any consideration of the ways people behaves when engaged in risk tasking must accommodate personal levels of monetary risk tolerance.

In relation to willingness, many affective perspectives and personality traits require future examination in view of the perplexing connection between decision making and emotions (Hariharan et al., 2015). Various forms of inspiration could influence the levels of exertion and effort people might want to apply to a particular kind of behaviour. Such effects would also depend on definite indicators (Yildiz et al., 2019). Moreover, despite its significance, the requirement for financial guidance is not commonly appreciated (Kramer, 2016). A retiree who encounters a situation of disastrous financial trouble may well have been able to implement a saving plan during their employment, but they failed to do so (Hershey et al., 2007). The majority of Malaysians over 60 are unprepared to confront future financial shocks, as revealed by previous research (Hamid & Chai, 2017). They were found to suffer from insufficient assets and resources to maintain their retirement lifestyle (Saieed, 2017).

Biopsychosocial

Engel’s extensive biopsychosocial model (1977) posits numerous factors related to biology, psychology (incorporating consideration, feeling, emotions and behaviour) and society (such as socio-environments and culture) (Vögele, 2015). The current ongoing study integrated the biopsychosocial aspect into the model to create a solid, secure and adequate picture of the financial empowerment of Malaysian women in their post-retirement period. The relationship between retirement and psychological well-being might depend on the settings or conditions in which the retirees actually retired (Fleischmann et al., 2020). Psychological distress was higher in those with less fortunate psychosocial working circumstances (such as burdensome work requests, limited decision-making power and work strain), less fortunate social living environments and more cumulative risk factors (Li at al., 2021). Husniyah et al. (2020) undertook a cross-sectional study of Malaysian civil service sector employees and discovered that psychological aspects were often associated with their financial issues. These ranged from their locus of control to self-esteem, orientation in the future, and materialist tendencies.

In addition, the characteristics of an individual's social state have been demonstrated to be firmly connected with their health behaviour and outcomes, including their mental well-being (Alegría et al., 2018; Lund et al., 2018). In his study, Evans et al. (2003) mentioned that older adults who had previously confronted psychosocial stressors might be more mentally helpless when confronted by unfriendly environmental circumstances. Individual factors such as loneliness (Bulloch et al., 2017), a lack of communication through social networks (Degnan et al., 2018), and a high financial burden (Kivimäki et al., 2020) all increase the risk of poor emotional health. In their examinations, Resende and Zeidan (2015) also discussed how an individual's literacy, intelligence and biasness of psychological abilities would probably add to their capacity to begin financial planning and saving. Conversely, Cwynar (2020) stated that women are not guaranteed to act more impulsively when making monetary decisions.

Supporting theory

The Capacity-Willingness-Opportunity Model introduced by Hershey et al. (2013) was used as the theoretical underpinning for the newly developed and holistic female retirees’ financial security model, in addition to the Modigliani-Brumberg Life-Cycle Hypothesis (LCH) (1954). Long-term retirement motivations and the ways individuals behave financially as they age can be understood and explained by the life cycle (Da Silva et al., 2021)

The LCH economic theory examines how people spend and save money throughout their lives. As people progress through the many stages of life, they take their accomplishments and knowledge with them. Every working person eventually reaches retirement, a life transition fraught with financial management challenges which are mirrored in the LCH theory. Individual habits connected with saving and spending alter throughout the different stages of life according to the life-cycle effect of accumulated assets and the theory of allocation (Modigliani & Brumberg, 1954). Therefore, financial literacy is required to aid retired women in their decision making throughout the retirement planning life cycle, thereby reducing the likelihood of their making poor choices that could negatively impact their financial security.

Thus, building on this review of the relevant research, it was proposed that those with a firm grasp of financial knowledge capacity and who have saved and accumulated wealth in anticipation of their golden years, enjoy more retirement confidence. In contrast, financially illiterate individuals often make incorrect assertions about their own savings and retirement funds. Sound foundations in terms of being aware, knowledgeable, and skillfull, as well as having the right attitudes and behaviours, are needed if a person is to take the correct decisions that would benefit them financially and bring about financial security. Individuals will be more confident in their ability to make decisions and manage their finances when they feel assured in the knowledge that they are taking the right steps to fulfil their monetary aims for their retirement. This tends to give them the inspiration to find additional financial information.

Methodology

This research will be conducted in the Klang Valley area of Malaysia, which includes the states of Wilayah Persekutuan Kuala Lumpur (the nation's capital) and Selangor. Three phases of mixed-methods in approach will be conducted. Phase one of the research involved an analysis of the relevant literature to identify potential indicators for the proposed model. Retired women's financial security will be measured using four indicators: the three well-established aspects of Capacity, Opportunity, and Willingness, with the additional predictor of Biopsychosocial. Experts in retirement, such as those from the EPF, NGOs and private retirement companies, will be consulted in the second phase through Focus Group Discussions (FGD). In the study, the most salient features of financial security were identified through in-depth interviews with industry participants. Experts in the field will be consulted to refine the research questionnaire and guarantee the study's reliability and validity. The indicators and items generated, adapted and refined in the first step will be used to construct a series of questionnaire instruments in the second phase. A pilot study involving the distribution of thirty (30) questionnaires to retired women in the Klang Valley area will ensure the framework's reliability and increased the study's validity. The reliability test was performed using SPSS to ascertain the pilot study findings (refer to sub-section 3.1 below). The final step will be the questionnaire which will involve interviewing 300 women retirees in the Klang Valley. Partial least squares structural equation modelling (PLS-SEM) will be undertaken using the Smart PLS 3 software to analyse the completed survey data.

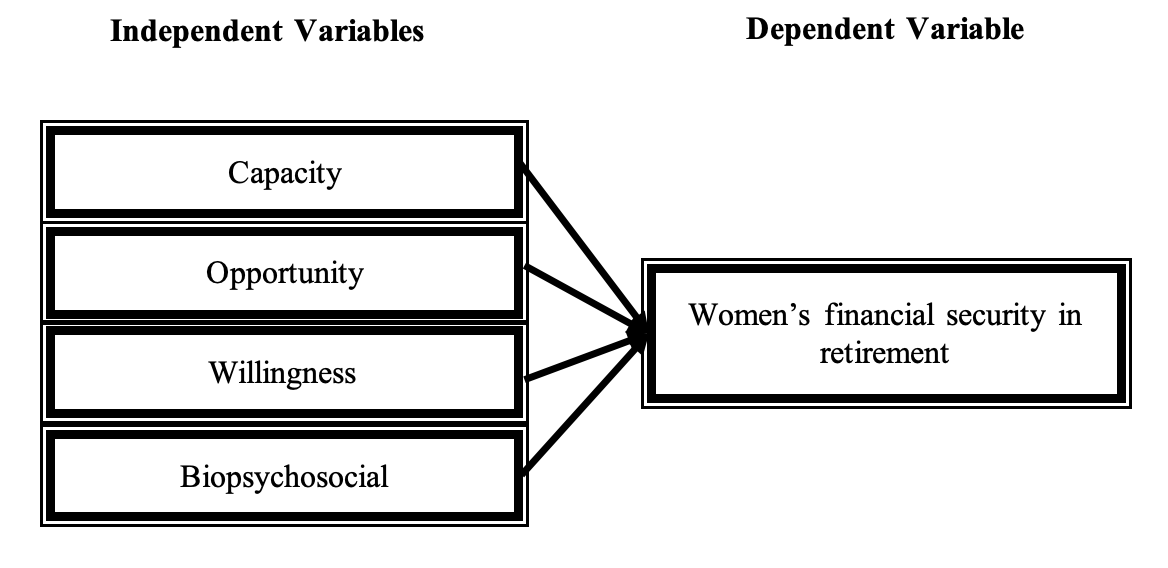

Based on the aforementioned literature review, the Capacity, Opportunity, Willingness and Biopsychosocial (COWB) model was adopted as a theoretical framework for analysing the elements influencing women pensioners’ characteristics and ability to remain financially secure in their retirement (Refer to Figure 1).

Pilot test

A pilot test was conducted before embarking on the actual and further analysis of the survey. Van Teijlingen and Hundley (2002) emphasised the significance of preliminary studies in finalising research, underlining the usefulness of pilot studies in meeting a variety of requirements and enabling valuable insights for the researchers. Further discussion is needed amongst researchers regarding both the process and outcomes of pilot studies. A pilot study can also be called a pre-testing or 'trying out' of a particular research instrument (Baker, 1994). In the current study, a pilot test was performed by taking a sample of thirty (30) respondents consisting of retired women then living in the Klang Valley area. The test was analysed by referring to the reliability test results which were based on the measurement of the Cronbach’s Alpha values. A Cronbach’s Alpha value of above 0.7 is considered highly reliable and an acceptable index (Nunnally & Bernstein, 1994), whereas a value of Cronbach’s Alpha of less than 0.6 is considered to represent low reliability. The output of the study was found to be highly consistent and reliable, as shown in Table 1 below.

Assuming the success of the abovementioned pilot test, the third phase of this research was performed next. The actual survey was distributed to 300 respondents in the Klang Valley area and dual-language questionnaires were provided in English and Bahasa Malaysia. The respondents’ inclusion criteria were retired women who are currently experiencing their retirement period and living in the Klang Valley. After the results are finalised using PLS-SEM, the authors decided whether or not the conceptual framework shown in Figure 1 is truly supported.

The subsequent paper arising from this study will provide further information about the contributions of the independent variables (COWB) to the dependent variable (financial retirement security of retired women). The paper will also provide detailed results after gathering all the information and data, data analysis and a final conclusion.

Model Contribution

The proposed retired women’s financial security model is grounded in four essential attributes - capacity, opportunity, willingness, and biopsychosocial - and could offer valuable assistance to the government in formulating relevant retirement-related policies. As reported by the Employees Provident Fund (EPF), early withdrawals were made from Malaysia's largest pension fund to ease the financial anguish of members reeling from the consequences of COVID-19. This has drastically eroded their retirement funds, leaving only 3% who can retire comfortably (Goh, 2021) and thus contributing to the issue of elderly women living in poverty after retirement. Consequently, the COWB model for long-term retirement planning is recommended, the aim being to educate working women so they can further enhance their retirement planning which would enable the ageing population of the country to age with better financial stability. This would contribute to Sustainable Development Goal 1 (SDG 1), which is linked to Malaysia's official aim of achieving poverty-free status by 2030. Hence, the proposed approach may contribute to Malaysia's SDG-related initiatives by helping to create a more financially stable elderly population. Having financially stable retirees would also contribute to achieving one aspect of the 12th Malaysia Plan (RMK12), which is to enhance the social re-engineering dimension's goal of improving people's well-being. Thus, a new model that facilitates the growth of a resilient ageing society is worth developing.

Discussion and Conclusion

The determination of this research is to accumulate information about the possible association of the Capacity-Opportunity-Willingness-Biopsychosocial Model on retirement planning and thus contribute to the prevailing body of knowledge in retirement frontier, with a particular emphasis on women retirees in Malaysia. Additionally, current research intends to recognise the critical components of the model in explaining women's financial planning prior to retirement. Greater financial stability is also expected to contribute positively. The findings of a study by Topa et al. (2018) indicated that when an employee participated in company-provided, retirement-oriented training and learning programs (which the authors regarded as an indicator of willingness), this enhanced their financial self-efficacy and planning for post-retirement employment. It would be wise for such measures to include a motivating perspective that would reignite the individual's preparation and saving routines, which was also inferred from the significant relationships of the willingness indicators. There has been considerable focus on how the retirement process affects women's adaptability and well-being in retirement, and the Biopsychosocial indicator in the COWB model has been accommodated in many different disciplines of psychology (Kerry, 2018). A strong correlation has been identified between one's levels of life satisfaction and biopsychosocial characteristics such as financial stability, retirement quality, and pension expectations (Siguaw et al., 2017). Therefore, women should consider the COWB framework when planning financially for their retirement since valuable elements may be added to their financial well-being, particularly given the major challenges they encounter and the complicated financial decision making they must perform throughout their lives. Working women who plan for a comfortable retirement would benefit from this model as awareness of early retirement financial planning grows. The consistent reliability statistics from the pilot test also strengthen the likelihood of this research in producing reasonable answers to the question of whether the variables used, actually have significant association with the financial retirement security of women retirees. In addition, these study findings will complement the goal of the 12th Malaysia Plan (RMK12) to enhancee people's well-being and the important Sustainable Development Goals outlined in Agenda 2030 to empower women and ensure zero poverty, especially among retired women.

Acknowledgement

We appreciate the support from Malaysian Ministry of Higher Education (MOHE) for funding the publication of this article through the Fundamental Research Grant Scheme (FRGS), 20190112FRGS.

References

Ahmad, S. Y., & Sabri, M. F. (2014). Understanding financial security from consumer’s perspective: A review of literature. International Journal of Humanities and Social Science, 4(12), 110-117.

Ahmad, S. Y., Sabri, M. F., Abd Rahim, H., & Osman, S. (2017). Factors predicting financial security of female headed households. Journal of Emerging Economies & Islamic Research, 5(1), 1-14.

Alegría, M., NeMoyer, A., Falgàs Bagué, I., Wang, Y., & Alvarez, K. (2018). Social Determinants of Mental Health: Where We Are and Where We Need to Go. Current Psychiatry Reports, 20(11).

Arham, A. F., Norizan, N. S., Ridzuan, A. R., Alwi, S. N. N. N. S., & Arham, A. F. (2019). Work-Life Conflicts among Women in Malaysia: A Preliminary Study. International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences, 9(9), 614-623.

Asebedo, S. D., & Wilmarth, M. J. (2017). Does how we feel about financial strain matter for mental health? Journal of Financial Therapy, 8(1), 5.

Bagozzi, R. P., & Dholakia, U. (1999). Goal Setting and Goal Striving in Consumer Behavior. Journal of Marketing, 63(4_suppl1), 19-32.

Bahaire, T., & Elliott-White, M. (1999). The application of geographical information systems (GIS) in sustainable tourism planning: A review. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 7(2), 159-174.

Baker, T. L. (1994). Doing Social Research (2nd ed.). McGraw-Hill Inc.

Brüggen, E. C., Hogreve, J., Holmlund, M., Kabadayi, S., & Löfgren, M. (2017). Financial well-being: A conceptualization and research agenda. Journal of business research, 79, 228-237.

Bulloch, A. G. M., Williams, J. V. A., Lavorato, D. H., & Patten, S. B. (2017). The depression and marital status relationship is modified by both age and gender. Journal of Affective Disorders, 223, 65–68.

Byrnes, J. P., Miller, D. C., & Schafer, W. D. (1999). Gender differences in risk taking: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 125(3), 367-383.

Chan, M. C. H., Chung, E. K. H., & Yeung, D. Y. (2021). Attitudes Toward Retirement Drive the Effects of Retirement Preparation on Psychological and Physical Well-Being of Hong Kong Chinese Retirees Over Time. The International Journal of Aging and Human Development, 93(1), 584-600.

Cwynar, A. (2020). Financial Literacy, Behaviour and Well-Being of Millennials in Poland Compared to Previous Generations: The Insights from Three Large-Scale Surveys. Review of Economic Perspectives, 20(3), 289-335.

Da Silva, E. A., Silva, C. A., Guerra, M., Rech, I. J., & Nazaré, S. R. M. (2021). Life cycle and retirement choices. Journal of Business and Economics, 670.

Degnan, A., Berry, K., Sweet, D., Abel, K., Crossley, N., & Edge, D. (2018). Social networks and symptomatic and functional outcomes in schizophrenia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 53(9), 873–888.

Dickason, Z., & Ferreira, S. (2018). Establishing a link between risk tolerance, investor personality and behavioural finance in South Africa. Cogent Economics & Finance, 6(1), 1519898.

Department of Statistics Malaysia (DOSM). (2018). Statistic data, Department of Statistics Malaysia. Retrieved on 2019, March 1 from https://www.dosm.gov.my/v1/index.php?r=column/cthemeBy Cat&cat=149&bul_id=OXFBWHJVYXhRNkhsL2ptRlg4QjNrZz09&menu_id=U3VPMldoYUxzVzFaYmNkWXZteGduZz09

Department of Statistics Malaysia (DOSM). (2020). Current Population Estimates, Department of Statistic Malaysia. Retrieved on 2022, November from https://www.dosm.gov.my/v1/index.php?r= column/cthemeByCat&cat=155&bul_id=OVByWjg5YkQ3MWFZRTN5bDJiaEVhZz09&menu_id=L0pheU43NWJwRWVSZklWdzQ4TlhUUT09#:~:text=Malaysia's%20population%20in%202020%20is,rate%20of%200.4%20per%20cent

D'Silva, B., D'Silva, S., & Bhuptani, R. S. (2012). Assessing the financial literacy level among women in India: An empirical study. Journal of Entrepreneurship and Management, 1(1), 46.

Engel, G. L. (1977). The Need for a New Medical Model: A Challenge for Biomedicine. Science, 196(4286), 129-136.

Evans, G. W., Wells, N. M., & Moch, A. (2003). Housing and Mental Health: A Review of the Evidence and a Methodological and Conceptual Critique: Housing and Mental Health. Journal of Social Issues, 59(3), 475-500.

Farrar, S., Moizer, J., Lean, J., & Hyde, M. (2019). Gender, financial literacy, and preretirement planning in the UK. Journal of Women & Aging, 31(4), 319-339.

Feldman, D. C. (1994). The decision to retire early: A review and conceptualization. The Academy of Management Review, 19(2), 285.

Fen, N. S. (2018). Towards better retirement well-being. Social protection insight A better tomorrow. Kumpulan Wang Simpanan Pekerja, 6, 13-21.

Fleischmann, M., Xue, B., & Head, J. (2020). Mental health before and after retirement—Assessing the relevance of psychosocial working conditions: The Whitehall II prospective study of British civil servants. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B, 75(2), 403-413.

França, L. H. F., & Hershey, D. A. (2018). Financial Preparation for Retirement in Brazil: A Cross-Cultural Test of the Interdisciplinary Financial Planning Model. Journal of Cross-Cultural Gerontology, 33(1), 43-64.

Gibson, R., Michayluk, D., & Van de Venter, G. (2013). Financial risk tolerance: An analysis of unexplored factors. Financial Services Review, 22(1), 23–50.

Goh, T. E. (2021). Malaysia EPF’s early withdrawals amid covid-19 leaves just 3% who can afford to retire, Asia Asset Management. Retrieved on 2022, November https://www.asiaasset.com/post/25222-epfretirement-gte-1101

Grable, J. E., & Lytton, R. H. (2001). Investor risk tolerance: Testing the efficacy of demographics as differentiating and classifying factors. Journal of Financial Counseling and Planning, 9, 61–74.

Haines, V. A., Godley, J., Hawe, P., & Shiell, A. (2009). Socioeconomic disadvantage within a neighborhood, perceived financial security and self-rated health. Health & Place, 15(1), 383-389.

Hamid, T. A., & Chai, S. T. (2017). Meeting the needs of older Malaysians: Expansion, diversification and multi-sector collaboration. Malaysian Journal of Economic Studies, 50(2), 157-174.

Hariharan, A., Adam, M. T. P., Astor, P. J., & Weinhardt, C. (2015). Emotion regulation and behavior in an individual decision trading experiment: Insights from psychophysiology. Journal of Neuroscience, Psychology, and Economics, 8(3), 186-202. https://doi.org/10.1037/npe0000040

Hawley, C. B., & Fujii, E. T. (1993). An empirical analysis of preferences for financial risk: further evidence on the friedman-savage model. Journal of Post Keynesian Economics, 6(2), 197-204.

Hershey, D. A., Jacobs-Lawson, J. M., McArdle, J. J., & Hamagami, F. (2007). Psychological Foundations of Financial Planning for Retirement. Journal of Adult Development, 14(1-2), 26-36.

Hershey, D. A., Jacobs-Lawson, J. M., & Austin, J. T. (2013). Effective financial planning for retirement. In M. Wang (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of retirement (pp. 402–430). Oxford University Press, Inc.

Husniyah, A. R., Amirah Shazana, M., Mohamad Fazli, S., Mohd Amim, O., & Roziah, M. R. (2020). Psychological factors contributing towards financial problem among civil service sector employees, Malaysian Journal of Consumer and Family Economics, 25(S1),148-156

Jianakoplos, N. A., & Bernasek, A. (1998). Are women more risk averse? Economic Inquiry, 36(4), 620-630.

Juen, T. T., & Sabri, M. F. (2012). Factors affecting retirement confidence among women in peninsular Malaysia government sectors. Malaysian Journal of Consumer and Family Economics, 19, 53-68.

Kerry, M. J. (2018). Psychological antecedents of retirement planning: A systematic review. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 1870.

Kivimäki, M., Batty, G. D., Pentti, J., Shipley, M. J., Sipilä, P. N., Nyberg, S. T., Suominen, S. B., Oksanen, T., Stenholm, S., Virtanen, M., Marmot, M. G., Singh-Manoux, A., Brunner, E. J., Lindbohm, J. V., Ferrie, J. E., & Vahtera, J. (2020). Association between socioeconomic status and the development of mental and physical health conditions in adulthood: A multi-cohort study. The Lancet. Public Health, 5(3), e140–e149.

Kramer, M. M. (2016). Financial literacy, confidence and financial advice seeking. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 131, 198-217.

Lange, A., Prenzler, A., & Zuchandke, A. (2012a). How do insured perceive their financial security in the event of illness? —A Panel Data Analysis for Germany. Value in Health, 15(5), 743-749.

Lund, C., Brooke-Sumner, C., Baingana, F., Garman, E., Breuer, E., Chandra, P.S & Haushofer, J., Herrman, H., Jordans, M., Kieling, C., Medina-Mora, M., Morgan, E., Omigbodun, O., Tol, W., Patel, Vikram., & Saxena, S. (2018). Social determinants of mental disorders and the sustainable development goals: a systematic review of reviews. The Lancet Psychiatry, 5, 357-369.

Lyons, A. C., Grable, J. E., & Joo, S-H. (2018). A cross-country analysis of population aging and financial security. The Journal of the Economics of Aging, 12, 96–117.

Mahal, A., Seshu, M., Mane, S., & Lal, S. (2012). Old age financial security in the informal sector: Sex work in India. Journal of South Asian Development, 7 (2), 183–202.

Marshall, G. L., Kahana, E., Gallo, W. T., Stansbury, K. L., & Thielke, S. (2021). The price of mental well-being in later life: the role of financial hardship and debt. Aging & Mental Health, 25(7), 1338-1344.

Mathew, N., Joseph, S., & Joseph, C. (2020). An Empirical Analysis on Investment Behavior among working Women: Are Women Taking the right Investment Decisions for their Future? Indian Institute of Management Kozhikode, 04th International Conference on Marketing, Technology & Society 2020.

Modigliani, F., & Brumberg, R. (1954). Utility analysis and the consumption function: An interpretation of cross-section data. In K. Kenneth, & K. Kurihara (Ed.), Post Keynesian Economics (pp. 388-436). Rutgers University Press.

Mukong, A., Shiwayu, N., & Kaulihowa, T. (2020). A decomposition of the gender gap in financial inclusion: evidence from Namibia. African Journal of Business and Economic Research, 15(4), 149-169.

Nga, J. K. H. (2018). An exploratory model on retirement savings behaviour: A Malaysian study. International Journal of Business and Society, 19(3), 637-659.

Ngui, N. (2016). Malaysians are borrowing too much, not saving enough. The Star Online. 30 August. Retrieved from https://www.thestar.com.my/business/business-news/2016/08/30/khazanah-malaysians-borrowing-too-much/

Nunnally, J. C., & Bernstein, I. R. (1994). Psychometric Theory (3rd edition). McGraw-Hill.

OECD. (2018). Financial education and saving for retirement. Why financial education is needed for retirement saving. Improving financial education and awareness on insurance and private pensions. Retrieved on 2022, November from

Olsen, A, & Whitman K. (2007). Effective retirement savings programs: Design features and financial education. Social Security Bulletin, 67(3), 53-72.

Olsen, R. A., & Cox, C. M. (2001). The influence of gender on the perception and response to investment risk: The case of professional investors. Journal of Psychology and Financial Markets, 2(1), 29-36.

Rai, K., Dua, S., & Yadav, M. (2019). Association of financial attitude, financial behaviour and financial knowledge towards financial literacy: A structural equation modeling approach. FIIB Business Review, 8(1), 51–60.

Resende, M., & Zeidan, R. (2015). Psychological biases and economic expectations: Evidence on industry experts. Journal of Neuroscience, Psychology, and Economics, 8(3), 160-172.

Robb, C. A., & Woodyard, A. S. (2011). Financial knowledge and best practice behavior. Journal of Financial Counseling and Planning, 22(1), 60–70.

Roy, P., & Patro, B. (2022). Financial Inclusion of Women and Gender Gap in Access to Finance: A Systematic Literature Review. Vision: The Journal of Business Perspective, 26(3), 282-299.

Sabri, M. F., Mokhtar, N., Ho, C. S., Anthony, M., & Wijekoon, R. (2020). Effects of gender and income on Malaysian’s financial capability. Malaysian Journal of Consumer and Family Economics, 24, 124-152.

Saieed, K. (2017, February 25). Do you save enough for retirement? The Star Online. https://www.thestar.com.my/business/business-news/2017/02/25/do-you-save-enough-for-retirement/

Sartori, T., Coronel, D. A., & Vieira, K. M. (2016). Preparaà § ã o para aposentadoria, bem estar financeiro, decisões e há bitos para a aposentadoria: um estudo com servidores de uma instituià § ã o federal [Preparing for retirement, financial well-being, decisions and habits for retirement: a study with employees of a federal institution]. Observatorio de la Economía Latinoamericana/ Observatory of the Latin American Economy, (226).

Selvadurai, V., Kenayathulla, H. B., & Siraj, S. (2018). Financial literacy education and retirement planning in Malaysia. MOJEM: Malaysian Online Journal of Educational Management, 6(2), 41-66.

Sharma, M., & Kota, H. B. (2019). The Role of Working Women in Investment Decision Making in the Family in India. Australasian Accounting, Business and Finance Journal, 13(3), 91-110.

Shukri, A. (2014). With Zero Savings, Most Malaysians May Face Dire Straits. The Edge Financial Daily. Retrieved on 2022, November 27 from http://www.theedgemarkets.com/node/171825

Siguaw, J. A., Sheng, X., & Simpson, P. M. (2017). Biopsychosocial and retirement factors influencing satisfaction with life: New perspectives. The International Journal of Aging and Human Development, 85(4), 332–353.

Tai, T. L., & Sapuan, N. M. (2018). Retirement planning In Malaysia: Issues and challenges to achieve sustainable lifestyle. Turkish Online Journal of Design Art and Communication, 8(SEPT), 1222–1229.

Topa, G., Lunceford, G., & Boyatzis, R. E. (2018). Financial Planning for Retirement: A Psychosocial Perspective. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 1-8.

Yao, R., Sharpe, D. L., & Wang, F. (2011). Decomposing the age effect on risk tolerance. The Journal of Socio-Economics, 40(6), 879–887.

Yeung, D. Y., & Zhou, X. (2017). Planning for retirement: Longitudinal effect on retirement resources and Post-retirement well-being. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 1300.

Yildiz, H. E., Murtic, A., Zander, U., & Richtnér, A. (2019). What fosters individual-level absorptive capacity in MNCs? An extended motivation–ability–opportunity framework. Management International Review, 59(1), 93-129.

van Teijlingen, E., & Hundley, V. (2002). The importance of pilot studies. Nursing Standard, 16(40), 33-36.

Vögele, C. (2015). Behavioral medicine. International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences, 463-469.

Wang, M., & Wanberg, C. R. (2017). 100 years of applied psychology research on individual careers: From career management to retirement. Journal of Applied Psychology, 102(3), 546-563.

World Economic Forum. (2020). Global gender gap report, World Economic Forum, Geneva. Retrieved on 2022, November from http://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_GGGR_2020.pdf

World Health Organization. (2018). Ageing and health. Retrieved on 2022, November from http://www.who.int/en/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/ageing-and health

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

18 August 2023

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-963-4

Publisher

European Publisher

Volume

1

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-1050

Subjects

Multi-disciplinary, Accounting, Finance, Economics, Business Management, Marketing, Entrepreneurship, Social Studies

Cite this article as:

Nadia Zainuddina, H., Azhar Mohamad, N. E., Rajaduraic, J., & Sapuan, N. M. (2023). The Conceptualization of Cowb Model Towards Women’s Financial Security. In A. H. Jaaffar, S. Buniamin, N. R. A. Rahman, N. S. Othman, N. Mohammad, S. Kasavan, N. E. A. B. Mohamad, Z. M. Saad, F. A. Ghani, & N. I. N. Redzuan (Eds.), Accelerating Transformation towards Sustainable and Resilient Business: Lessons Learned from the COVID-19 Crisis, vol 1. European Proceedings of Finance and Economics (pp. 306-319). European Publisher. https://doi.org/10.15405/epfe.23081.27