Abstract

Pandemic period has changed the world and, as well, the problems teachers are confronted with. So, it cannot be seen any longer as an unwanted episode, but as a learning opportunity to rethink teacher education from the teacher resilience perspective. Building and sustaining a resilient teacher by teacher education programs becomes the request of the day. In Romania, as well as in many countries, the concept teacher resilience competence is quite new. As a learning outcomes, it was not explicitly used, stipulated or promoted by legislation, academic assessment standards or by pre-service or in-service teachers’ study programs and activities. Considering that teacher resilience is more than a personal or an individual responsibility, the paper presents some findings of our research: the meanings of teacher’s resilience competence concept, the need to consider the teacher’s resilience as a transversal competence, paradigms in exploring teacher resilience, the transfer potential of some building teacher resilience models and proposals for a proper integration of them in teacher education programs.

Keywords: Competence, protective and risk factors, teacher education, teacher resilience

Introduction

Context of changes and teacher education problems

It seems that 21st century society is defined by at least three types of fundamental and correlated changes: complex, rapid, and often unpredictable. Transformations are bivalent, positive and negative and can be examined in terms of benefits and challenges. In recent years, more and more weightings have emerged between the two plans, with the predominance of crisis situations. The Covid pandemic19 is a recent and conclusive example that illustrates the three characteristics mentioned above and the serious turbulence generated in various registers: social, economic, medical and, last but not least, educational and professional. Schools closed at various intervals, the simplified curriculum, the exclusive focus of education on digital techniques and online courses severely disrupted the teaching – learning - assessment processes; cognitive educational goals and especially the socio-affective ones of educating students have been undermined. The reopening of the schools required special protection measures and different behaviors then the pre-epidemic stage. Student training is difficult to recover and only partially. Measures taken in educational policies and practices have often been fluid, short-term, initiated more punctually than on a stabilized basis.

Of course, the ambiguity or irrelevance of decisions can be explained, to a certain extent, by the absence of any precedents. Certainly, there is a need to invent new strategies to make the school, the teaching staff and the students able to cope with new, difficult and high-risk situations.

Problem Statement

The context we referred to affected the initial and in-service training of teachers and the quality of their professional services. Detailing and nuanced the three characteristics initially mentioned, some researchers have promoted and examined the implications of the VUCA concept that designates the "new normal" in which teachers are formed and function: V - volatility (fluidity, turbulence in thought and action patterns previously considered “normal”); U - uncertainty ((uncertainty, doubts about the possibility of predictions); C - complexity (the multitude of components, causes and effects of a situation or event); A - ambiguity (information and unclear, incomplete or contradictory measures) (Hadar et al., 2020, pp. 573-586).

Against the background of the pandemic, the spectrum of negative consequences has widened and diversified; training was devoid of an essential component, school practice, the mentoring system was suspended, the transition from face-to-face to online system complicated and increased the difficulty of teachers' tasks, many of them lacking the necessary expertise to convert the curriculum to the digital version. Unwanted transformations have occurred psycho-socially and emotionally; stress and anxiety increased and teachers' well-being eroded. Although some teacher training programs have tried to cope with extreme external conditions, have revised their objectives, developed rapid digital education courses, tried to capitalize on the potential of simulation games or case studies, however, the signs of a teacher training crisis have not diminished significantly. Reality has exceeded the functional responsiveness of teachers and students. These events, phenomena and consequences show unequivocally that education systems, teachers and students have not had and still do not have adequate resources to deal with new situations. Consequently, it is necessary, as a matter of priority, to include in the inventory of professional skills teachers have of the. The development of this type of competence is justified not only in relation to exceptional events but also due to the nature of the professional activity of teachers that requires continuous reconnections to the dynamics of change, even every day (daily resilience) of the professional context. A student's educational needs do not remain constant in a school year or during the school years; a class of students knows different stages of evolution, parallel classes may have different configurations, motivations and performances, in some classes violence is present, in others not. There are differences between urban and rural areas; teachers need to adapt and possibly anticipate such changes by reorganizing their system of knowledge, skills, attitudes and aptitudes. Surprisingly, at least so far, teacher resilience has not been a distinct goal of initial and continuing training programs even in evolved education systems (Netherlands, UK, USA, Australia); at best, only a few issues were addressed without, however, a multidimensional approach to resilience. Socio-affective skills that are substantially related to resilience have also been minimized.

Research Question

If resilience becomes an urgent professional need, both in current and special, extreme conditions, are there also the necessary resources of knowledge and action capable of achieving it?

The answer to this question involves considering the following findings:

There are different points of view regarding the nature of the teacher's resilience and the perspectives of the approach; we need a valid integrative concept;

Some models and experiences of cultivating teacher resilience have been developed but research on teacher resilience is relatively recent and, therefore, the body of knowledge available probably does not cover all the needs for theoretical and practical construction; however, the initiation of new research should be complementary to the use of existing data.

Purpose of the Study

Based on and in relation to the two statements above, the objectives of our presentation are:

- Clarifying the conceptual and value meaning of teacher resilience.

- Determining research paradigms and their relevance in addressing teacher resilience.

- Identifying models with high potential of transfer regarding the development of teacher resilience.

- Formulation of a set of suggestions on teacher training programs from the perspective of teacher resilience.

Research Methods

The research capitalizes on content analysis (educational policy documents, international comparative studies, synthesis papers, analytical articles, etc.) and the authors' experience in teacher training and in the evaluation and accreditation of national and international programs on teacher education.

Findings

Teacher resilience: conceptual meanings and value

The conceptualization of resilience from the perspective of teachers and in relation to training programs has a relatively new history, it is a new field of educational investigation. ‘Teacher resilience is a relatively recent areas of investigation which provides a way of understanding what enables teachers to persist in the face of challenges and offers a complementary perspective on the studies of stress, burnout and attrition’ (Beltman et al., 2011, p. 185). This is one perspective.

Day and Gu (2014) offer us another milestone in understanding the meaning of resilience: “Effort to increase the quality of teaching and to raise standards of learning and achievements for all pupils must focus on effort to build, sustain and renew teacher resilience and their effects must take place in initial training” (p. 22).

A definition that meets broader consensus is developed by Masten (2014) who considers resilience “the capacity of a dynamic system to adapt successfully to disturbances that threaten system function, viability and development” (p. 10). Here the word ‘system’ aims at different plans: individual, school, organizational, community, etc. The concept, as such, knows successive restructurings and enrichments of its semantic area. If initially it designated the ability of a subject to respond appropriately to extreme risk situations, then the range of situations was broadened, without being reduced to exceptional events. Similarly, there is an ongoing transition from the assessment of resilience to a return to the original, normal state. Thus, resilience tends to increasingly consider the development, refinement of previously initiated actions. Finally, there is an evolution from the stage of negative effects of ‘fragile’ resilience to the development of strategies and methods for building and implementing resilience.

The constructs associated with teacher resilience are varied. In our opinion, they could be classified into three relevant categories, which we will call:

- determining or influencing factors (e.g. personal or individual traits, particularities of contextual resources);

- functional factors (protective factors that support and facilitate the approach and solution of the problem situation, and risk factors - negative influences that block or diminish the functional response to the risk situation);

- dimensions of teacher resilience: professional dimension (factors related to the exercise of the profession, teaching-learning-assessment), motivational dimension (intrinsic / extrinsic motivation), emotional dimension (emotions with positive / negative valences) and socio-relational dimension (relational factors: relationships with students, with colleagues, with the school manager).

In a coherent approach, the interaction of the three categories of constructs can be represented by a matrix that highlights the complexity of the phenomenon (Table 1). For example, the socio - relational dimension (4) depends on the individual factors (A) but also on the contextual ones (B), and the last two categories should also be examined from the perspective of their protective (A4Pf) or risky (A4Rf) influence.

Paradigms of teacher resilience

The literature has identified several paradigms, of which at least four are considered major:

- The paradigm of focusing on personality (ideographic model) refers to the exploration of personality factors that positively or negatively influence the assertion and development of resilience; for example: protective factors (intrinsic motivation, perseverance, reflexive abilities) and risk factors (lack of self-confidence, disorganized emotions, difficulties in establishing interpersonal relationships, etc.);

- Contextual paradigm. The contextual paradigm involves identifying resources, contextual protective factors and also risk factors; for example, the first category includes: mentoring, the support provided by the administration and colleagues and, in the second, heavy workload, lack of resources, classes of students with very heterogeneous compositions, schools with problems. If the traditional approach to the ideographic paradigm (focusing on personality) ignores context, the paradigm in question draws attention to the relevance of the particularities of the context. Teachers face a variety of situations / environments with varying degrees of complexity and novelty that they should control.

- Procedural paradigm. The procedural paradigm is a processual approach interested in the interaction between personality and contextual factors (socio - ecological perspective). As Beltman considers, „resilience lies at the interface of person and context, where individuals use strategies that enable them to overcome challenges and sustain their committment and sense of wellbeing” (Beltman, 2021, p. 15). We note that individual and contextual factors are no longer treated separately, but integrated into a process governed by resolving strategies. The latter become the core of research.

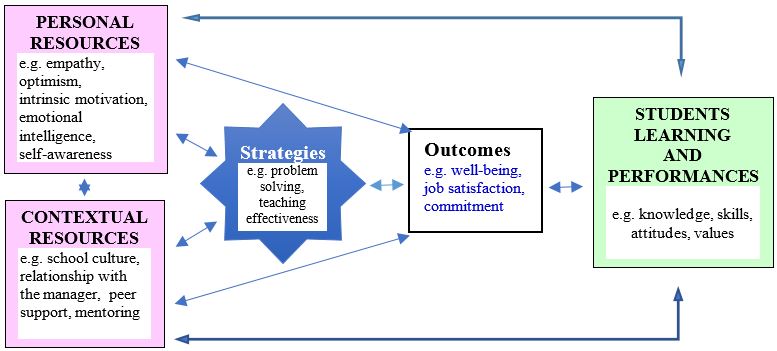

- Systemic paradigm. The systemic paradigm is an integrative one that incorporates, in a correlated way, the personal, contextual and procedural perspective to which are added the effects of resilience. The figure 1, The systemic paradigm of teacher resilience, illustrates the types of factors and the relationships between them. The systemic paradigm is an adaptation of the model developed by Beltman (2021, p. 21) to which we added the Student learning and performance block that refers to the effects of teacher resilience on students' learning outcomes and performance and, as well, we detailed the content of each block, using different sources.

There are some implications of the systemic paradigm:

- It allows a better understanding of teacher resilience, demonstrating the complexity of this competence and its position in a hierarchy of the competences of the teacher;

- It inspires research by indicating possible directions of investigation, with multiple focuses and less explored area. In accordance with this model or capitalizing on one or more of the considered options, international and national research has already been developed (e.g. BRiDE, ENTREE);

- It is relevant for the construction of teacher training programs indicating the influencing factors, functional factors and dimensions to be taken into account. In some countries, specific models have been developed that value these perspectives;

- Discusses different models and evaluation of resilience, claims the use of appropriate tools to validly measure the competence of resilience as we are interested not only in the consequences of each predictive factor, but also about the size of the effect, the share of influence of various factors. For example, according to empirical research, it seems that the contextual factor - the weight of tasks to be performed, school culture, managerial support - is more influential than individual resources in terms of job satisfaction, wellbeing and burnout reduction (Ainsworth & Oldfield, 2019);

- Draws attention to researching the benefits of resilience for both teacher and student;

- The responsibility for the level of resilience does not lie solely with the educator; contextual factors and strategies learned in training activities are also responsible. Therefore, the responsibility is not only individual but also collective.

Examining the concept and analyzing the directions of research on teacher resilience leads us to the conclusion that teacher resilience is a particular type of professional competence (Potolea & Toma, 2019), with a socio-emotional dominant. Moreover, we would be tempted to argue that teacher resilience is a mega-competence because it integrates a complex of generic social, cognitive and emotional skills (problem-solving, communication, cooperation, copying skills, emotions management).

Models with high potential of transfer regarding teacher resilience

The opinions regarding the teacher resilience competence are different and this is, to a large extent, the result of the absence of consensus regarding the definition of the concept. Some authors emphasize individual characteristics or other factors that favor or hinder the development of resilience. Others evaluate it based on the strategies used by people facing adversity, thus addressing resilience as a process (Ionescu, 2011) or as a system (Beltman, 2021), each of those views having a specific impact on designing teacher education programs.

Two Australian projects, BRiTE () and Staying BRiTE () demonstrate that resilience can be nurtured in early career teachers through collaborative partnerships between university teacher education programs and schools. On a solid evidence-based approach on dimensions of resilience (profession-related, emotional, motivational and social), five online learning modules to support teacher resilience were developed inside the BRiTE project:they were integrated into coursework to support reflective engagement and contextual understanding (Beltman et al., 2011). As an extension of the BRiTE modules has been developed a sixth module,, which explores as a resilience resource for teachers. Because BRiTE modules can be personalised, interactive and adaptable to different contexts, they are used in different ways in teacher education programs, by individual teachers and pre-service teachers within and beyond Australia.

The European Project ENTREE (ENhancing Teacher REsilience in Europe) encompasses six training modules: Resilience; Building Relationships; Emotional Well-Being; Stress Management; Effective Teaching; Classroom Management, and an additional module named ‘Education for Well-Being. The project (http://www.entree-online.eu/) provides diverse learning opportunities and tools for teachers, is carried out via a self-assessment tool, online professional development modules, face-to-face training, live webinars, and online materials and publications on teacher resilience and it is supported by a team of international experts from five European countries and from Australia (Peixoto et al., 2018). 764 pre-service teachers from Germany, Ireland, Malta and Portugal answered to a questionnaire including perceptions of individual (e.g. teacher efficacy, commitment, personal life) and social/contextual (e.g. school support, social context) factors, as well as a global evaluation of resilience. Teachers were assisted to draw on personal, professional and social resources, to “bounce back” and to also thrive professionally and personally, and to experience job satisfaction, positive self-beliefs, personal wellbeing and an ongoing commitment to the profession. Results showed that self-efficacy appears as one of the key factors related to resilience, differences in the relationships between the variables were found according to each country, suggesting that resilience is influenced by the context in which teachers live and work.

There are other projects who applied the tools developed by ENTRÉE and BRITE programs in other contexts. One of them is Project LITBSAY (), developed în 2019, who aimed at developing Dutch teacher resilience with the support of mentors (Mansfield, 2021, p. 152), and, another one, Project CARE who presented the benefits of mindfulness training on teachers’ social and emotional competence and the quality of classroom interactions (Jennings et al., 2017), in the United States, where, as Sikma underlines:

The focus of most teacher preparation programs is on the intellectual aspect of the job, and teachers enter the profession with the capacity to teach effective lessons, but not necessarily with the tools to help them cope with the emotional stressors (Sikma, 2021, p. 85).

Suggestions on teacher training programs from the perspective of teacher resilience

These are some of the projects that demonstrate the need to renew higher education programs on teacher education to maintain its relevance to changing societal and personal needs of the future teachers. While some countries have legal or regulatory provisions that contain guidance for the preparation, mitigation, response, return, or resilience of schools and universities, the concept ‘teacher resilience’ is quite absent in Romanian legislation on educational policies and strategies. Although there are some recommendations for teacher education programmes to prepare graduates particularly with regard to managing stress, the term ‘resilience’ is used rarely by schools managers and teacher educators. Sometimes, they use it in a reactive way, and in a rather ad hoc manner, that is, mainly in response to topics, cases or problems their new teachers bring in and not in a systematic way. So, we consider that the results of researches on resilience, the BRiTE framework, the findings from ENTREE and from other national and international projects can be used as a starting point to rethink Romanian teacher education curricula from the perspective of teacher resilience. The proposed (Table 1) and the systemic paradigm of teacher resilience (Figure 1) may be used as two conceptual and methodological tools to gain more understanding on the concept of resilience, to rise teachers awareness about these topics, to identify good practices in educational programs and in schools that develop teachers resilience, to have a curriculum that emphasises a problem-based and an interdisciplinary approach, to design new projects on factors and strategies that enhance resilience in teachers or, as well, to design a master program of study in teacher resilience-building strategies.

Conclusions

Teaching can be stressful but, also, wonderful!

To deal with the challenges related to education, the teachers must know the meaning of resilience concept, and to recognize, develop, and use the resources / situations / factors that increase their resilience, their students’ resilience and, as well, their schools’ resilience.

Teacher resilience competence is not a natural thing, it must be learned and developed by involving all the educational stakeholders: universities, school managers, professional communities.

Resilience must become part of the culture of the universities which offer training programs for pre-service and in-service teachers and of the schools where pedagogical practice is carried out. School leaders, mentors, colleagues have to be able to support new teachers to become resilient.

Teacher resilience becomes; it cannot be considered an additional task that can be postponed any more. To ensure the teacher profession’s sustainability, must be given opportunities to develop competence in resilience.

References

Ainsworth, S., & Oldfield, J. (2019). Quantifying teacher resilience: Context matters. Teaching and Teacher Education, 82, 117–128. DOI:

Beltman, S. (2021). Understanding and Examining Teacher Resilience from Multiple Perspectives, In C. F. Mansfield (Ed.), Cultivating Teacher Resilience. International Approaches, Applications and Impact (pp. 11-26). Springer.

Beltman, S., Mansfield, C., & Price, A. (2011). Thriving not just surviving: A review of research on teacher resilience. Educational Research Review, 6(3), 185-207. DOI:

Day, C., & Gu, Q. (2014). Resilient teachers, resilient schools: Building and sustaining quality in testing times. Routledge.

Hadar, L. L., Ergas, O., Alpert, B., & Ariav, T. (2020). Rethinking teacher education in a VUCA world: student teachers' social-emotional competencies during the Covid-19 crisis. European Journal of Teacher Education, 43(4), 573-586. DOI:

Ionescu, S. (2011). Traité de résilience assistée [Assisted resilience treaty]. Presses Universitaires de France. https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/27419624-trait-de-r-silience-assist-e

Jennings, P. A., Brown, J. L., Frank, J. L., Doyle, S., Oh, Y., Davis, R., Rasheed, D., DeWeese, A., DeMauro, A. A., Cham, H., Mark, T., & Greenberg, M. T. (2017). Impacts of the CARE for teachers program on teachers’ social and emotional competence and classroom interactions. Journal of Educational Psychology, 109(7), 1010–1028. DOI:

Mansfield, C. F. (Ed.). (2021). Cultivating Teacher Resilience. International Approaches, Applications and Impact. Springer.

Masten, A. S. (2014). Ordinary magic: Resilience in development. The Guilford Press.

Peixoto, F., Wosnitza, M., Pipa, J., Morgan, M., & Cefai, C. (2018). A Multidimensional View on Pre-service Teacher Resilience in Germany, Ireland, Malta and Portugal. In M. Wosnitza, F. Peixoto, S. Beltman, & C. F. Mansfield (Eds.), Resilience in Education. Springer, Cham. DOI:

Potolea, D., & Toma, S. (2019). “Competence” concept and its implications on teacher education. Journal of Sciences of Education and Psychology, IX(LXXI), No. 2/2019, 1-9. http://jesp.upg-ploiesti.ro/index.php?option=com_phocadownload&view=category&id=32:journal-vol-ix-lxxi-no-22019&Itemid=16

Sikma, L. (2021). Building Resilience: Using BRiTE with Beginning Teachers in the United States. In Mansfield, C. F. (Ed.), Cultivating Teacher Resilience. International Approaches, Applications and Impact (pp. 84-101). Springer.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

10 April 2023

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-961-0

Publisher

European Publisher

Volume

5

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-1463

Subjects

Education sciences, teacher education, curriculum development, educational policies and management

Cite this article as:

Potolea, D., & Toma, S. (2023). Rethinking Teacher Education From the Perspective of Teacher Resilience. In E. Soare, & C. Langa (Eds.), Education Facing Contemporary World Issues - EDU WORLD 2022, vol 5. European Proceedings of Educational Sciences (pp. 1143-1151). European Publisher. https://doi.org/10.15405/epes.23045.115