Abstract

As in any other profession, the teaching profession often shows marked differences in professional development. In academia, different career paths are often explained by reference to the principles of meritocracy. However, there are plenty of situations where academic success is not necessarily due to merit, but rather to the informal situations in which academic actors may find themselves. One of the perceptible images could be that of multiple informal networks, constantly intersecting and exchanging information in a game of domination, for the acquisition of the resources needed to gain professional advantage. The present research set out to investigate how informal communication structures in a university organisation influence academic career developments. Adopting an interpretive perspective, the investigative approach involved interviewing nine academics from three different scientific fields (Philology, Technology, and Economics) and led to explanations that focused around the concepts of Becoming and Obtaining. This subsequently allowed us to identify possible scenarios and evolutions of academic careers and to understand how informal communication networks influence three of the important aspects in the development of an academic career: teaching activity, research activity, institutional relations.

Keywords: Academic career, constructivist grounded theory, informal communication networks

Introduction

Although it is a place where the principles of meritocracy seem to mediate the professional development of its members more than in any other existing social environment, academia is also a place where we meet several unconscious bias (Gvozdanović, & Bailey, 2020; Gvozdanović, & Maes, 2018) which could often true the say that sometimes it's not what you know, it's who you know (Di Leo, 2003; Pifer & Baker, 2013) or even more it's not just who you know, but how you know them (Nordling, 2022).

Such an approach to the evolution of academic careers opens the premise of revealing non meritocratic ways for professional achievement (Way et al., 2019; Zivony, 2019) and understanding the mechanisms of academic success by revealing the importance of social ties between individuals in order to achieving the personal goals (Stadtfeld et al., 2019).

Discussions about personal goals occur through informal communications, communications that represent a deviation from the planned structure of organisational communication that generate, over time, patterns of unplanned interactions known as informal communication networks. Their emergence is therefore made possible by the physical closeness of the participants and the common career or friendship interests they share.

In Atkinson and Moffat' (2005) understanding, an 'informal network' is a group of individuals who find it mutually beneficial to stay connected with each other. Such social structures develop through human interactions based on trust, shared values and beliefs, facilitating multiple exchanges of information.

While research so far has pointed to their unscheduled and interactive nature, rich information content, colloquial language, and absence of a predetermined agenda as features of informal communication networks (Kraut et al., 1990), the idea of personal goals adds a new perspective to the understanding of informal communication networks. It is a perspective in which the intentionality of achieving a personal goal opens up the possibility of knowingly scheduling unscheduled meetings in order to maximize the acquisition and attainment of professional advantages. More than that, Koch and Denner (2022) highlighted that informal communication is a good way to increase job satisfaction through the feeling of being informed and affectively involved.

Symbolic membership of influential departmental structures is a resource that can bring potential and/or immediate benefits in the development of an academic career. Having, through one's personal communication network, links with the people who dominate the academic environment at university level or within one's scientific field is often a time-consuming resource. However, the symbolic value of informal relationships and the possibility of subsequent benefits are likely to encourage academics to cultivate such informal communication networks (Leisyte & Enders, 2011).

Leisyte and Enders (2011) noted that active engagement in developing interpersonal relationships has as its main objectives identifying influential people (with whom should one develop relationships?), adopting the best ways of relating (how to communicate with others?) and setting one's own professional goals (for what purposes should I develop a particular relationship?). Such an approach is likely to develop subsequent strategies for gaining the trust of colleagues and superiors, based on the positive meanings they attach to various types of behaviour. Adopting the behaviours expected by the community is a condition for professional success and a way of strategically cultivating informal collegial relationships (Pifer & Baker, 2013) in the circumstances where sometimes, in order to access information related to a possible promotion, the use of informal communication networks can be a real advantage (Van Miegroet et al., 2019).

Problem Statement

Academia should by definition be a place of meritocracy. In this sense, academic career development should take into account objective criteria that intensively and extensively measure the performance of academic actors.

Academic reality, however, also reveals situations in which the performance of academic actors is achieved as a result of the right associations where it is more important who you associate with than who you really are. One of the most studied of these situations is the mentor-mentee relationship.

Bäker et al. (2020) showed that of the three types of mentors investigated (teachers, sponsors and/or collaborators), the sponsor position of the mentor seems to mediate to the greatest extent the mentees obtaining tenured positions in the shortest time.

Li et al. (2019) examined the influences of collaborations between junior and senior researchers and found that a senior's top researcher position provides a very important competitive advantage to the junior in building a future academic career.

Lorenzetti et al. (2019) went even further and analysed the impact of peer mentoring. The findings indicate that peer mentoring positively influences academic, social, psychological and career development.

Domunco (2017, 2018) has shown through the Becoming-Obtaining model that belonging to informal communication networks creates the conditions for acquiring or losing benefits and privileges that influence the career path of a university teacher.

Thus, academic actors tend to place their academic career optimization actions in a two-dimensional space, characterized by the presence of two processes that define their career path: Professional Development and Academic Titles and Positions. The sense of professional becoming is defined in terms of personal satisfaction, resulting from the belief that a job is well done, and social recognition, coming from the respect of other members of the academic community as a result of the quality of work done. An academic who has a sense of professional development is a selfless person who excels in the main areas of academic activity (teaching and/or research) and is a positive role model for other members of the academic community. Professional obtaining refers to the results achieved by an academic, which are quantified in the acquisition of academic positions, privileges and benefits. Differences in personal ways of valuing the two processes indicate that academic actors develop their academic careers by focusing on one of three directions of action: Becoming, Obtaining, Becoming & Obtaining (Domunco, 2018).

The result of focusing academic actors on one of the three action routes is that of fast or slow development in their academic career, but also of acquiring different social statuses that we find in two routes focused on Becoming or Obtaining. On the route where the focus is on Becoming we find: the Resemnauts (fail neither to become nor to achieve), the Perfectionists (first become and then achieve), the Great Teachers (become and achieve at the same time). On the route where the focus falls on Obtaining we have: The Achievers who get but never become, The Meticulous who first get and then become and The Great Managers who get and become at the same time (Domunco, 2017).

In such a context, where membership of different types of informal networks influences the development of an academic career, it becomes necessary to understand how they affect the main aspects that characterize the exercise of the academic teaching profession: teaching and research activities, institutional relations.

Research Question

The research question this approach is based on is:

How informal communication networks influence the development of academic careers?

Purpose of the Study

The aim of the research is to build a grounded theory model related to the role that informal communication networks play in the evolution of academic careers.

Research Methods

Talking about the role of informal communication networks in one's career development could be an uncomfortable experience for the research subjects, producing defensive reactions. Given the increased likelihood of incomplete and especially distorted information, we adopted the Constructivist Grounded Theory (CGT) perspective, which aims to develop a detailed understanding of social or psychological processes in an analysed context (Charmaz, 2006) by exploring social interactions and structures in detail. In CGT research, the notion of reality is discovered by the researcher through interviews with research participants. The final interpretations therefore belong to both the researcher and the participant(s), becoming a shared reality.

Given the fact that in the generation of grounded theories the detailed exploration of individuals' subjective experiences and the understanding of meaning construction processes are processes that underpin the whole research approach, we used the intensive interview because it is one of the most commonly used data collection methods in this methodology (Charmaz, 2006).

Nine teachers who entered the academic environment at the same time but had different academic trajectories were interviewed in the study. The subjects who participated in the research came from the fields of economics, philology and engineering sciences.

Findings

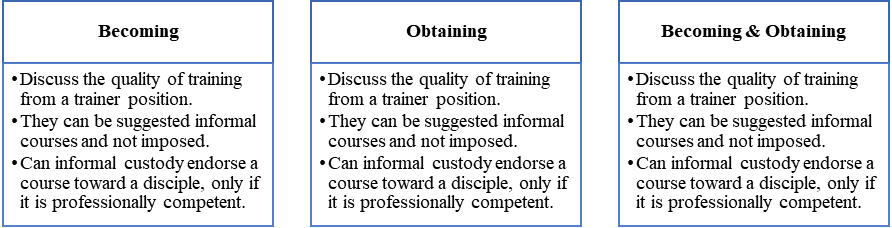

Placement on one of the three academic tracks leads to different perceptions and particularized uses of informal communication networks (Domunco, 2017, 2018). To capture these issues, we sought to identify the role played by informal communication networks on three dimensions that can enhance or hinder academic advancement: teaching activities, research activities, institutional/administrative activities.

Teaching

Within this dimension, there were important differences in the position adopted towards informal communication networks, both in terms of the direction of action (see Figure 1) and the specialisation of the teachers who participated in the research.

The data processing revealed an important contradiction for university actors adopting the Becoming route. Although centred on the teaching component of their academic career, academics with this life perspective do not use informal communication networks to improve their courses or their progression in front of students:

Of course it is desirable and must... Yes, we talk amongst ourselves normally (about improving courses), but I can't make it a goal. (i8)

The explanations on this issue differ according to the scientific fields of the academics interviewed. In this sense, the reason for not using informal networks on the teaching dimension is that of egos in the case of philologists,

There is a...again...pride, a pride of my saying... I think it's more important or less important, but it's my saying. (i1-9)

... there is an egoism of the one who has a judgment and keeps it to himself. And I'm sure it works... some keep the judgment and put it in their book, some keep it and don't put it anywhere... or give it to students. (i1-9)

or that of minimizing the importance of psycho-pedagogical training in teaching, in the case of those coming from technical specializations:

With us it's how you do it, not how you say it... We engineers practice. That's the problem... (i1-9)

At the other end of the spectrum, those who obtain and become at the same time use informal communication networks to enhance not just their own course, but the entire programme of study in which they work:

Changes in one discipline must enter into dialogue with changes in other disciplines... an organic, structural matter. Therefore, I can make some changes, but I have to take into account what is happening in other disciplines and then I have to have a dialogue with colleagues, unquestionably. (i3)

For each of the three strategic directions of academic career development, there were mentions of the involvement of informal communication networks in supporting the acquisition or allocation of courses through mechanisms specific to academic arrivisme:

Situations of course allocation on criteria other than competence? They exist and I don't think they are fair... from my point of view... But sometimes you do them because of need, but that doesn't mean that you've taken someone, through your informal network, that course. If, however, from the point of view of preparation it's not better than you, it's really a matter that has been regulated to you by your informal network. (i4)

I found myself called to do a course... that in the syllabus someone else has proposed, instead of me proposing the course that I do myself.... A dissatisfaction, but there is an explanation that I am forced to accept and... I tolerate the situation without difficulty. I wasn't there when the fortune was shared, right? Someone else did and in the meantime asked me if I didn't want to make it already thought of. (i9)

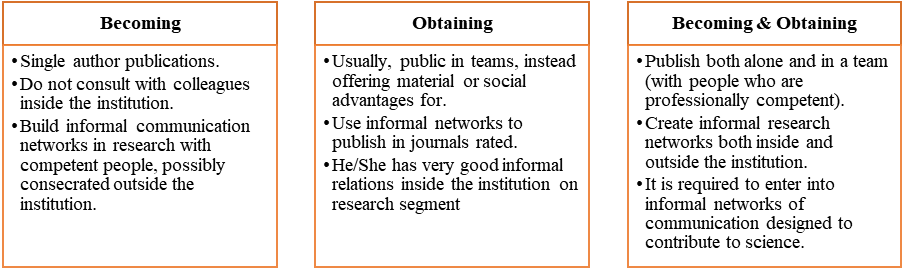

Scientific Reasearch

The involvement of informal communication networks in the scholarly development of a university teacher follows the same logic of professional becoming and obtaining (see Figure 2).

For those who want to achieve, informal networking is a way to accumulate the points needed for advancement. In this case, the informal facilitates the emergence of so-called scientific ticks, interested in publishing in a group, but without having a relevant scientific contribution:

There may be such citations. This is a typical example of informal relationships... that, after all, if you're friends with a colleague, they pass you co-author and you pass them co-author. (i3)

I was a PhD student and the professor was only listed like that, or something like that.... (i4)

The thing about networks promoting you to publish, going round in circles... promotion-development... suggests to me so much... image-centricity... that I... reject it. (i9)

Facilitating professional development and obtaining benefits through research activities is associated on the one hand with the belief that

The evolution in an academic career (...) must necessarily be linked to research. Even if up to a certain level, e.g. lecturer or head of research, the research component may not be dominant, later on, however, the research component should be compulsory, because the university aims to take science one step further. Each decade, if you like, must ensure the evolution of society, the evolution of science in general. You can't make science evolve without research, there is no other way (i5).

and on the other hand, that informal networking is a way that offers multiple possibilities to become a better researcher:

In the scientific field we pursue common research directions, we can complement each other... the most important thing is to complement each other in our work, to achieve a result. A project to write, a paper to write, a project to carry out. (i4)

When we're in a team it's easier, because we set deadlines... Let's say that by next Saturday we have to meet and work so, so, so... And if we're in a team we have to respect deadlines, especially if I, a lot of times being the initiator of the article, I have to set a good example and then we respect. (i7)

O the research dimension, we identified significant differences in both the approach to academic careers and specialisations. If philologists display the same loneliness in teaching and in scientific research,

... in our (philologists') case the style is the information itself, i.e. how I say it is very important because this how I say it becomes content and then I cannot associate with another colleague... (i1-9)

Again it's specific to the field where... you don't say your opinion, because it's yours, and if you say it, you find it on the other's page. (i1-9)

Those coming from a technical background are most open to group research:

I don't even remember doing one (article) alone in my life. (i1-9)

... quotations are very little forced... they come by themselves... as long as we are in a network with common concerns, obviously we know each other's achievements best and obviously we end up quoting... not out of interest or because someone asks us to, but because... we really have to... because the articles overwhelmingly result from each other. (i1-9)

While in economics it is usually between the two extremes:

Working as a team and the results of my projects being often team-based, I have often published as a team, at least in the last while - but there are also times when I publish alone. (i1-9)

On the research dimension, networks can be built both inside and outside the university. The first category, those who become and then achieve, being usually isolated within their institution, will seek to legitimize their internal position by appealing to external networks:

More I have gained externally, so I have friends externally, apart... with whom I meet, I know, at conferences. (...) Outside the university even in the country, let's say, I have more reliable friends, let's say... I don't know... maybe it's like eyes that see each other less often... I don't know but... (there are people) in whom I can always base myself on this kind of things... (i1).

I can otherwise talk to the people there... I can contact them by phone... so that I can find out what's the trend in research and especially in journals (i3).

In addition, I don't know... as far as I'm concerned... it wasn't... it wasn't very well regarded my external collaboration. Why? I don't know... A kind of reaction so... rejection.... that more or less expressed... (i8)

Those who are more focused on getting will aim to associate their names with scientific personalities:

Because now the emphasis is on collective citations, citations between university centres, citations outside. The collective of authors should be from abroad or be top 500 authors that pull you up. If you publish with someone in the top 500 and they cite you from China, Japan then things become known... (i1)

Professional development and obtaining involves developing research networks both inside and outside the institution:

For my part, when I publish a book or an article, I generally share it with friends. They are not necessarily colleagues from university, but they read the work and have a dialogue sometimes... on those texts and then I have the environment to modify, to edit, to add, to change, to see other people's points of view... I think that's important actually (i6)

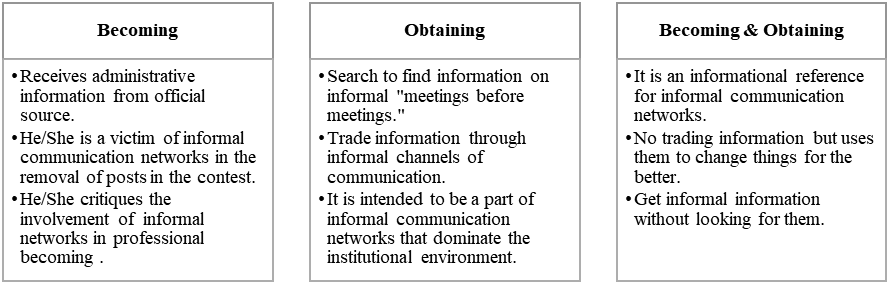

Institution

The development of an academic career also involves entering into a certain institutional relational routine (see Figure 3). In general, academics who follow the Becoming - Obtaining and Becoming & Obtaining routes have entered the system because they have been propositioned based on previous performance.

A person involved at the time, interested in developing university education here, contacted the company where I worked and asked for some recommendations. From there I was recommended along with three other colleagues, some of whom are still here in the university... With that professor who contacted us we met, we discussed informally, to see what should be done... (i2)

When I finished university I came out top of my class and then it was easier for me to be selected in the team. (i3)

Those on the Obtaining - Becoming trajectory usually self-promote through informal personal networks:

I, working as a collaborator here, have also tried... through, let's say, unofficial channels, to find out if there are any positions available and if I could... I think the proposal came from me (to come to the university). (i7)

Once at university, collegial relationships are inevitably created and evolve over time. The interviews revealed that regardless of the specialisation of the teachers participating in the research, they described the early period of their academic careers in positive affective terms:

It was many, many, many hours... many, many hours... It was tiring... it was very tiring. Sometimes we had 10 teaching hours a day. It would squeeze you as young as we were, but it was nice! (i5)

... It was like when we were younger the collaboration was stronger between us. (...) I have the feeling that we were more united then... maybe because we were younger and we were more enthusiastic and the enthusiasm united us. I have the feeling that today's young people are also more united and have more solidarity and more common concerns... and maybe they spend even more time together. (i6)

When I came to the university, relations were very good. Really good! (i8)

Over time, the dynamics of informal relationships evolve differently, depending on the academic routes chosen. For those who Become and then Obtain, the informal networks of youth tend to enter a process of contraction. Accustomed to making respect for rules and tradition an end in itself, academics in this category are distinct from those who adopt behaviours typical of academic arivism. In general, the disappearance of the initiator or builder of the academic structure, usually a mentor professor, was indicated as a trigger for the negative evolution of informal relationships,

... the evolution wasn't the happiest... there were times when relationships broke down... but... in... the first that I know of... I'd say... 10 years maximum... the relationships were... almost perfect. I had the chance to have an exceptional mentor (...) who had I don't know... an art... a craft so... special... to hold people together... to harmonize... to... to polish... of... smoothing out the rough edges. We'd meet and talk, and... we were even envied by those around us for the harmony that reigned among us... ..maybe... ...maybe, at some point, this harmony will be restored... I don't know... (i8)

After our mentor was gone, I personally felt that... (sighs)... I mean... from where you used to reach out and touch that one and that one, at some point it seemed to me that, I was bumping into the fence. That walls were born between us and you hit the fence, you don't hit each other's bodies... just like that slowly, slowly, slowly. (i9)

and the competition for higher university degrees that brought out envy and self-interest:

... maybe... I don't know... maybe also the time when we were all pretty much on the same level so... there weren't really... or there weren't noticeable such... problems. After that... maybe people start to become more I don't know... more envious or... I don't know... what do I know. It may be that... but in the end... and envy, if it's not positive, because there's constructive positive envy... can distort relationships between people and distort them very badly. (i7)

Those who follow the Obtaining - Becoming path, and for whom the attainment of the goal matters first and foremost and not the ethics of the actions of attainment, are more detached in creating informal relationships:

...are informal discussions... at which... I have access to now because... I have another position. But before I didn't have that access... Yes, indeed, to move up gives you the opportunity to go to other... channels... let's call them informal. If you're... careful enough to keep your channels back... it's very good... and that's what I try. (i7)

The Career Development and Obtaining axis also implies a different positioning from informal communication networks at institutional level. These are seen as sources of advancement that enhance quality of being and provide the community with strong arguments to legitimise the possession of academic positions and privileges:

Informal networking becomes all the more important in the academic and intellectual environment in general because you have access to other perceptions (i2).

You have to openly, selflessly pass on information to all the people who are in the hierarchy above you as well as below you. Only to the extent that it will be understood that everyone has to be involved in this kind of networking that is at some point the university... only to the extent that everyone pushes to the same cart will the whole network survive and everyone will benefit. If there are elements of selfishness, of information blocking, we have no chance of surviving. (i3)

The research data revealed that informal communication networks created at institutional level can sometimes influence career advancement, mainly through lobbying for vacancies and the candidate selection process:

After all, there are situations when the committee is composed of teachers, executives, proposed by the candidate... (i2)

Of course there are, I mean... unquestionably areas of influence... A post can be put out to tender because... let's say, someone might indeed apply and all that person's friends have some influence over the decision on who decides. (i3)

In some situations (informal communication networks) can even be decisive in... the evolution of a... a teacher, a researcher, because you don't have to be a professor... (i8).

Conclusions

Empirical observations have shown that there are differences in the perception of the informal phenomenon both within and between the scientific fields of the teachers participating in the research. Systematic comparisons between the collected data led to the identification of common patterns, gathered under the theoretical concepts of Becoming and Getting, concepts that capture a wide range of communication situations, strategies for professional career development and mechanisms for generating and managing informal communication networks in three areas of interest for academic career development: teaching, research, institutional relations.

The two main concepts of the Becoming-Obtaining theoretical model offer new insights into understanding differentiated academic career developments. The idea of Becoming expresses the tendency to achieve professional fulfilment by focusing the academic on acquiring symbolic things (recognition, respect, etc.), while the idea of Gaining is equivalent to the desire to gain concrete things (financial advantages, academic positions, etc.). In this way, the free will of the academic seems to have to choose between acquiring on merit and acquiring at any cost.

We believe that the present paper proves its usefulness by revealing new perspectives on the nature of academic human nature: fairness and/or imposture, sociability and/or isolation, social openness and/or closeness, etc. Underlining these dualities is likely to provide a respite for rational analyses and decisions, aimed at reorganizing personal conceptions of people and professional life in academic education. We believe that the Becoming/Obtaining model can become, in time, an argument to rethink the policies of training and recruitment of university teachers and, even if it is slightly utopian, university education to be dominated by Great Teachers and Great Managers.

References

Atkinson, S. R., & Moffat, J. (2005). The Agile Organization. From Informal Networks to Complex Effects and Agility. Control Research Programme (CCRP) Publications.

Bäker, A., Muschallik, J., & Pull, K. (2020). Successful mentors in academia: are they teachers, sponsors and/or collaborators? Studies in Higher Education, 45(4), 723-735. DOI:

Charmaz, K. (2006). Constructing grounded theory: A practical guide through qualitative analysis. Sage Publications.

Di Leo, J. R. (2003). Affiliations: Identity in Academic Culture. University of Nebraska Press.

Domunco, C. F. (2017). Informal communication networks and professional evolutions in academic career. In T. D. Chicioreanu, G. M. Ianoș, & L. Manasia (Eds.), Modernity and competitiveness in education (pp. 101-111). Editura Universitară.

Domunco, C. F. (2018). Professional Obtaining & Becoming Model – a Way to Explain Unequal Academic Career Paths. Revista Romaneasca pentru Educatie Multidimensionala, 10(4), 92-104. DOI:

Gvozdanović, J., & Bailey, J. (2020). Unconscious bias in academia: A threat to meritocracy and what to do about it. The Gender-Sensitive University (pp. 110-123). Routledge.

Gvozdanović, J., & Maes, K. (2018). Implicit bias in academia: Athreat to meritocracy and to women’s careers - and what to do about it. League of European Research Uni-versities (LERU), Leuven.

Koch, T., & Denner, N. (2022). Informal Communication in Organizations: Work Time Wasted at the Water-Cooler or Crucial Exchange Among Co-workers? Corporate Communications: an International Journal, 27 (3), 494-508.

Kraut, R. E., Fish, R., Root, R., & Chalfonte, B. (1990). Informal communication in organizations: Form, function, and technology. In S. Oskamp, & S. Scacapan (Eds.), Human reactions to technology: Claremont symposium on applied social psychology. Sage Publications.

Leisyte, L., & Enders, J. (2011). The strategic responses of English and Dutch university life scientists to the changes in their institutional environments. In: J. Enders, H. De Boer, D. Westerheijden (Eds.), Higher Education Reform in Europe. Sense Publishers.

Li, W., Aste, T., Caccioli, F., & Livan, G. (2019). Early coauthorship with top scientists predicts success in academic careers. Nature Communications, 10(1). DOI:

Lorenzetti, D. L., Shipton, L., Nowell, L., Jacobsen, M., Lorenzetti, L., Clancy, T., & Paolucci, E. O. (2019). A systematic review of graduate student peer mentorship in academia. Mentoring & Tutoring: Partnership in Learning, 27(5), 549-576. DOI:

Nordling, L. (2022). Getting the job: it's not just who you know, but how you know them. Nature.

Pifer, M. J., & Baker, V. L. (2013). Managing the Process: The Intradepartmental Networks of Early-Career Academics. Innovative Higher Education, 38(4), 323-337. DOI:

Stadtfeld, C., Vörös, A., Elmer, T., Boda, Z., & Raabe, I. J. (2019). Integration in emerging social networks explains academic failure and success. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 116(3), 792-797. DOI:

Van Miegroet, H., Glass, C., Callister, R. R., & Sullivan, K. (2019). Unclogging the pipeline: Advancement to full professor in academic STEM. Equality, Diversity and Inclusion: An International Journal, 38(2), 246-264. DOI: 10.1108/edi-09-2017-0180

Way, S. F., Morgan, A. C., Larremore, D. B., & Clauset, A. (2019). Productivity, prominence, and the effects of academic environment. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 116(22), 10729-10733. DOI:

Zivony, A. (2019). Academia is not a meritocracy. Nature human behaviour, 3(10), 1037-1037. DOI:

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

10 April 2023

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-961-0

Publisher

European Publisher

Volume

5

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-1463

Subjects

Education sciences, teacher education, curriculum development, educational policies and management

Cite this article as:

Florin Domunco, C. (2023). The Role of Informal Communication Networks in Academic Careers. In E. Soare, & C. Langa (Eds.), Education Facing Contemporary World Issues - EDU WORLD 2022, vol 5. European Proceedings of Educational Sciences (pp. 1081-1093). European Publisher. https://doi.org/10.15405/epes.23045.109