Abstract

Discourse multimodality and the impact of new technology on teaching resources in the framework of digital education have called for more customised learning experiences. ESP (English for Specific Purposes) learners are facing such a transition with a stringent need to access educational resources that allow for meaningful and authentic contexts of interaction, be them synchronous or asynchronous. To cater for these learning needs, ESP instructors must also become innovative content creators, among other roles such as multicultural instructor, growth mindset promoter or professional communicator. Projecting these dynamic educational scenarios, the ESP teacher can facilitate and enhance communicative language learning by juxtaposing collaborative (specifically gamified learning experiences) and task-based approaches. In building customised communicative learning frameworks for ESP learners, educators empower them to expand their language learning horizons by using communication as the vital instrument. It is the purpose of this contribution to examine how task-based language learning can be paired with digital pedagogy to create sustainable learning resources, stemming from emoji-encrypted language chunks to deciphering emoji-based idioms. Likewise, the study aims to explore the potential of using these resources to foster storytelling as a communicative language learning approach and to analyse the efficiency of using this practice with Preschool and Primary School Pedagogy undergraduate students throughout the ESL classes and enabling learners to share their learning experience for peer assessment.

Keywords: Communicative language learning, collaborative learning, emoji code, gamified learning, learner autonomy

Introduction

The process of online teaching and learning English for Specific Purposes (ESP) to digital natives has multiple implications, from content design, to delivery and structure of learning materials and to digital assessment. With students whose learning needs stem from readiness to explore new media and apps to being granted more learner autonomy, to being motivated and actively engaged in the teaching and assessment processes, teaching ESP poses new challenges in the realm of digital language pedagogies. Founded on the principle of being able to communicate real meaning as an indicator of learning a language, the communicative approach stands out as the mainstream instrument of teaching/ learning in the ESP class. Beyond the primary purpose of facilitating complex and effective language learning, Ur reckons that digital ESP teaching/learning also needs to create scenarios for the subsequent principles of language pedagogy, namely building on educational values, the creation of a positive classroom climate and student motivation (2012).

In shaping authentic ESP learning contexts in the digital framework, the design and use of the communicative approach can bond methods and approaches such as task-based language learning approach and collaborative approach with digital assessment instruments via gamification, creating thus sustainable learning resources. Even more so, in the blended format that teaching/learning might take in the post-pandemic world, there is a stringent need to design and use resources that are recyclable and easily adaptable to educational needs and learning contexts.

With a wide array of apps and platforms available online, there is a growing temptation on behalf of instructors to constantly integrate such digital media in the teaching process. Despite their indisputable utility, the language pedagogical support of these apps is not yet fully tested, which means that using digital learning apps is rather experimental and can allow for an in-depth exploration. Gamification, referred to as “designing information systems to afford similar experiences and motivations as games go, and consequently attempting to affect user behaviour” (Koivisto et al., 2014; p. 3025), represents an inclusive and complex framework for (self-) assessment in this respect. Both supporting student motivation and facilitating an interactive and collaborative context of communication, gamification can be paired with a variety of tasks and assessment activities, enabling proper networking for these learners whose digital expertise calls for more practical learning scenarios.

To create genuine teaching and learning contexts online, we have chosen gamified assessment as an instrument of embedding the task-based approach and collaborative work in the ESP classes. In the current of the globalised society, several elements that are central to education need to be “reevaluated: education, educated person, learning, teacher and student” (Manea, 2014, p. 455), bearing significant implications in the dynamics of teaching. Moreover, digital teaching/ learning also implies that teacher roles need to expand into adopting the personas of social interaction facilitators, content creators and, to some extent, entertaining instructors so as to mimic face-to-face interactions. Therefore, gamified assessment - as the ‘process of applying game-based elements to assessment processes, in a deliberate attempt to either make them more appealing, enjoyable, engaging or less onerous to candidates’ (Guy, 2019) enables assessment constructs that allow for different communicative tasks in ESP teaching.

The endeavour of the current paper is to present how discourse multimodality can be integrated in the design of a digital ESP class, particularly in the framework of building communicative skills by using features of, a term coined by David Crystal as a new electronic medium of communication (2006) and as a virtual conversational alternative to using gamified assessment tools such as in order to formatively assess language acquisition skills. Moreover, it is the purpose of this study to explore how storytelling, as a communicative language learning approach can be used to enhance language acquisition through task-based vocabulary skills (idioms in particularly) and how such emoji-coded/ Netspeak features can be recycled and repurposed for communicative functions.

Literature review

The Communicative Approach- From Paradigm Shift to Hybrid and Online Learning Challenges

Reaching its popularity peak in the 1960-1070s, the communicative approach was a trailblazer in the methodology of teaching, challenging the hegemony of the grammar-translation method, intensely used by language instructors until then. Coining the communicative competence as “the ability to use a language that is studied in a specific social context” (Jalolov et al., 2015, p. 13), the communicative language approach (CLT) has shifted the teaching focus in terms of objectives, learner output, types of tasks, use of mother tongue, tests measures and teacher roles. The methodological changes that occurred along with the CLT represented a “healthy revolution, promising a remedy to previous ills: objectives seemed more rational, classroom activity became more interesting and obviously relevant to learner needs.” (Ur, 2012, p. 42)

Regarding language as social behaviour, Hymes referred to as a “term for the capabilities of a person” (1972, p. 272 ) introducing thus the features of CLT in terms of student-centeredness and contextual learning buzz words. Moreover, Savignon used the same term in order to “characterize the ability of learners to interact with other speakers” (1972, p. 1), drafting thus the dimensions of CLT features such as group work, active listener and interactivity. With CLT as the recent mainstream language teaching instrument, the advantages of shifting from the traditional grammar-translation method to the communicative approach are still difficult to quantify. Nonetheless, there are undeniable aspects that have led to improving the ESP teaching process, particularly that “the communicative approach has directed our attention to the importance of other aspects of language besides propositional meaning, and helped us to analyse and teach the language of interaction” (Swan, 1985, p .87).

The manner in which the communicative approach triggered changes at the level of approach, method, tasks, objective and teacher’s role was synchronised to social changes. The CEFR (Common European Framework of References for Languages: Learning, Teaching, Assessment) yet again moves the focus from mere learner-centred to a community-based approach, where learners need to gain language skills that enables them to “meet the needs of a multilingual and multicultural Europe by appreciably developing the ability of Europeans to communicate with each other across linguistic and cultural boundaries” (Language Policy Unit, 2001, p. 3). In this respect, the approach that CEFR considers- the social-action matrix accounts for “the action of the social agents, social action. Each methodology is defined fundamentally by the action for which it aims to prepare learners. For the communicative approach, it is language interaction, for the action perspective, it is social action” (Puren, 2020).

Even more so, in the scenarios of digital classes or the forthcoming hybrid teaching/learning scenarios, the challenges of the communicative approach resort to how multimodality can be embedded in the communicative function within ESP classes. “Online communication allows the check-over of received information at any necessary moment” (Manea & Stan, 2016, p. 318). If using a plethora of digital tools and apps might be rather promising, the pedagogical support is still insufficiently explored. The consequences of entering this uncertain realm of teaching/learning are yet to be seen, but the experimental perspectives that CLT provides lead the way to particularly enriching opportunities. Namely, the Netspeak influence upon digital language, along with the insertion of emojis into the mainstream networks and platforms can provide insightful resources for vocabulary tasks and for task-based and collaborative formative assessment.

From learning idioms to emoji-coded practice: conceptual and applied guidelines of the task-based approach

In the framework of the communicative approach in ESP teaching, the and language are prerequisites of the teacher input when introducing and assessing vocabulary learning sequences. Contextual learning and learner-centredness become guidelines in the language pedagogy and sketch authentic scenarios of retrieving and using previously taught vocabulary. Task-based language learning (TBLT) is “based on the principle that language learning will progress most successfully if teaching aims to create contexts in which the learner’s natural language learning capacity can be nurtured rather than making a systematic approach to teach the language bit by bit” (Ellis, 2009, p. 222). Using tasks as the basic unit of language production, Ellis identifies “input-based” and “output-based” (2009) tasks with reference to designing particular language skills to suit the contextual learning needs.

The focus in task-based approaches is on grasping meaning and using vocabulary in meaningful contexts, along with a set of features that dissociate TBLT from a basic situational grammar exercise. Particularly, these characteristics of the approach resort to using “some kind of gap” (Ellis, 2009)- either to convey information or to express learners’ opinion), to determine learners to make proper use of their own language resources and to strive for a well-defined outcome, with language being the mere means not the outcome itself. The need to increase learners’ exposure to vocabulary is a given in any ESP course and “the fact that vocabulary is learned incrementally leads to the implication that words must be met and used multiple times to be truly learned” (Schmitt, 2007, p. 749)

The main purpose in designing vocabulary teaching based on TBLT in our ESP class was to facilitate authentic learning and customise online learning with digital features of communication, embedding thus the Netspeak characteristics in both teaching and assessment sequences. “When talking about authenticity, teachers and material developers must consider first the field they are working with as to identify real-life scenarios the learners will encounter either in their academic or occupational lives” (Gonzalez et al., 2019, p. 80).

The particular manner in which we designed a part of the vocabulary acquisition process in the case of PIPP (Preschool and Primary School Pedagogy) undergraduates throughout the second semester of teaching the ESP course was to. Seen as a tool for encouraging students to communicate and understand conversational language, idiom acquisition represented an important section of teaching vocabulary in the ESP class. The ‘input-based tasks” were organised around introducing relevant vocabulary through idiomatic phrases and pairing explanations with Netspeak visual supports (i.e. memes), along with the “output-based tasks” in which learners were asked to compare and contrast English idioms with similar meaning Romanian idiomatic phrases.

Vocabulary learning through the lens of Netspeak dialects: emoji code and idioms

The digital framework of ESP challenged both learners and instructors into adapting written discourse to the language of the Internet, thus the impact of Netspeak became a common feature of online conversations and short written interactions. “Coined as a need of identifying a new Internet language, as a blend between speech, writing and electronically-mediated features” (Crystal, 2004, p. 48), Netspeak, as a new electronic medium of communication, expanded from its use in emails, chatgroups or social network into other communication instances, particularly during synchronous and asynchronous interactions in online classes. Present in the form of emojis, memes or gifs-often as a virtual expression of reactions to speech or text, Netspeak can provide a valuable resource for integrating multimodality in the process of teaching vocabulary.

Emojis “(from the Japanese [picture] + [character]) are graphic symbols with predefined names/IDs and code (Unicode), which include not only representations of facial expressions (e.g.,😄), abstract concepts (e.g.,🤒), and emotions/feelings (e.g.,❤), but also animals (e.g.,🐨), plants (e.g.,🌹) activities (e.g.,), gestures/body parts (e.g.,🙏), and objects (e.g.,🍴)” (Rodrigues et al., 2018, p. 394). These typographic symbols, also referred to as emoji code, are currently integrated in nearly all text-based digital interactions, rendering discourse more affective and being a digital alternative to paraverbal cues. The potential of integrating emojis in the process of teaching vocabulary is high, as online language cannot remain independent from the Netspeak print. Moreover, with the digital native’s expertise to embed digital linguistic cues in their online discourses and interactions, the use of emojis in the vocabulary skills acquisition could be appreciated by digital learners.

Idioms, in particular, represent a resourceful category of vocabulary items that can be paired with the emoji code, as idioms represent fixed expressions whose meaning cannot merely be predicted from the translation/understanding of the individual words that build them. There is, in this case, an inference exercise that learners need to perform while studying idioms, which is quite often a rather complex and strenuous task. The doubling of these vocabulary items with the visual cues provided by emojis will turn a learning task that if often seen as dull into an engaging guessing-game in which learners must use their logical and reasoning skills to match the emoji code to the correct idioms. There have been various “guess the emoji” games, but the use of emoji code with idioms as part of vocabulary teaching is a rather recent experiment among ESP instructors. The greatest advantage of such games is that it “creatively tests users’ capability to decode a string of emojis that represent books, songs, the name of films and even English idioms and phrases” (Jacob, 2020, p. 413). The learning challenge, in which learners are required to identify idioms based on emoji codes, was used in our ESP class as a method to encourage and stimulate incremental learning of idioms, in the first place. As a task-based vocabulary sequence, the guessing game was repeated along several ESP classes, for new idioms that had been taught along the semester and in combination with a set of other vocabulary practice tasks. It verified the principles of the task-based approach in as much as the game included a gap-type task- learners had to complete sentences with the correct idiom, and it allowed for the repeated practice of idioms in other forms than the standard grammatical tasks. Furthermore, it represented an authentic learning experience, in which the digital expertise in Netspeak was put to test, while also enabling students to practice their skills in using idioms.

To emphasise the incremental learning of idioms, the use of this vocabulary teaching strategy in our class consisted of solving multiple choice, fill in the blanks, respectively matching activities in a gamified format, either through Kahoot!/Quizizz apps or through Wordwall learning apps. The intention was to counterbalance the often difficult to study idioms with more interactive learning contexts and to encourage vocabulary increase through using idioms in short conversational interactions introduced as game-based sequences (learners had to choose the idiom by taking up a spin-the-wheel Wordwall activity and taking turns in continuing a dialogue based on idioms use).

Moreover, dwelling on the Netspeak dimension, learners practiced their idioms skills by unlocking emoji-based codes, the task catering for the above-mentioned features of the approach: meaning-focused, gap-solving, using their own skills to unlock the emoji-coded idioms and solving a puzzle-type challenge while using language as tool. Having practiced such scenarios of learning and using idioms in the vocabulary building process throughout several classes, learners were also required to complete a formative assessment challenge in the form of digital escape rooms, which also activated the collaborative feature in the communicative approach. The outcome was also to teach storytelling- a genuine competence that learners studying pedagogy have to build- and develop communication skills particularly through idiom-based knowledge.

Sustainability of vocabulary learning: Telling a story from emoji bits and pieces

Having established that a successful means of acquiring vocabulary skills is through systematic exposure to lexical items, language chunks or idioms, the manner in which this repeated exposure is organised by ESP instructors is also important. To better understand and get accustomed to practicing the vocabulary skills, learners require repeated encounters with the same vocabulary items, ideally in authentic learning contexts and under distinct task-based scenarios. After the exposure to assessment of idioms through emoji code guessing games, our intention throughout the ESP classes was to encourage learners to use these idioms while at the same time improving their productive skills (writing and speaking). The learning context that enabled this sort of practice was by resorting to, as a complex tool meant to enhance language skills in ESP.

Defined as “the vivid description of ideas, beliefs, personal experiences, and life-lessons through stories/ narratives” (Serrat, 2008) storytelling is deemed to be an essential competence for pre-service PIPP undergraduates. More than enabling learners to develop new literacies in terms of life skills and literacy, storytelling in ESP learning uses language as the vehicle for creativity and vocabulary skills, combining thus multiple competence skills.

The learning scenario focusing on blending storytelling and idioms use for PIPP learners referred to the following steps: learning the stages of a story, studying linking words and vocabulary for increasing narrative value (adjectives, short phrases) and respectively creating authenticity with the use of idioms. The task- a written one - required learners to write a story starting from a set of symbols and emojis and to use specific idioms that have been studied along the semester. Another similar task was assigned at the end of the semester, within a Digital Escape Room challenge, when the task was to assess spoken competence together with vocabulary skills. Particularly, learners had to create endings for stories they had to read, but which had been left unfinished, using emoji codes to generate ideas for their endings. The task was in the form of a recorded assignment, in which students recounted the endings of the stories either by a standard storytelling means or by attaching other multimodal features and turning it into digital storytelling.

More than exposure to pre-taught idioms and other vocabulary items, the task was also customised so as make vocabulary learning a sustainable process, by means of recycling resources- idioms, emoji codes, previous tasks of writing stories. With language as a mere instrument and not an outcome in itself, the purpose of this task allowed for an entertaining experience, for creativity and display of vocabulary skills.

The Collaborative approach and gamification dynamics: Digital Escape Rooms and interactive formative assessment

Described as a “coordinated, synchronous activity that is the result of a continued attempt to construct and maintain a shared conception of a problem” (Roschelle & Teasley, 1995, p. 70), the collaborative approach enhances social communication and interaction with the benefit of active and exploratory learning. With learners working together in order to achieve common learning goals, often done so by solving specific tasks, the collaborative approach makes learning more dynamic and an interactive experience. Online learning and teaching provide multiple contexts for collaborative experiences and gamification- particularly as a vehicle for formative assessment – is one solution. Other than using various apps and game-based learning strategies throughout the semester, our intention was to design and use a Digital Escape Room challenge at the end of the semester, structured as a means of revising topics and skills and of creating an interactive learning scenario.

An educational escape room represents:

An instructional method requiring learners to participate in collaborative playful activities explicitly designed for domain knowledge acquisition or skill development so that they can accomplish a specific goal (e.g. escape from a physical room or break into a box) by solving puzzles linked to unambiguous learning objectives in a limited amount of time (Fotaris & Mastoras, 2019, p. 235).

Digital escape rooms in ESP learning have the tremendous advantage of allowing instructors to scaffold tasks and individual skill assessment, while also enabling learners to cooperate as they race towards the completion of the educational goal.

Participants will be asked to interact with their peers to unlock hints in order to advance through the escape rooms, the strategy being to encourage them to interact verbally. The content of the tasks can also be designed so as to allow for customised assessment of speaking skills, by including tasks that require them to record themselves in audio-video formats (Mudure-Iacob, 2021, p. 212).

Having a strong motivational benefit, the use of Digital Escape Rooms in ESP teaching also require participants to make use of their critical thinking, problem-solving abilities and communication skills. Likewise, “by customising learning contexts and embedding formative assessment in gamified frameworks, teachers can fully expand the advantages of digital learning and create competitive study environments” (Mudure-Iacob, 2020, p. 106). Other advantages include the possibility of organising digital escape rooms as synchronous or asynchronous tasks, depending on the particular role of the instructor, either as facilitator, or as guiding spectator, in which case learner autonomy is increased.

The thematic scenario in which we used the Digital Escape Room challenge with our PIPP pre-service teachers was to create a virtual context in which participants were imaginary teachers who had to escape a locked school building in order to help their students pursue knowledge. The particular manner in which we embedded elements of vocabulary practice of idioms was through emoji codes, which players had to break and identify the correct idioms, the combination of answers giving them the chance to breakout of locked virtual rooms. Integrating numerous listening, reading, writing and vocabulary skills, the digital escape room also had a specific task based on assessing speaking skills through storytelling. Learners would study (based of multimodal resources- video-based, text-based, audio-based, map-based materials) about myths and legends around the world and, in an audio-video recording using Flipgrid, they had to remake and present the story through other cultural filters (Romanian, in our case).

This assessment scenarios allowed for blending multimodal resources, for organising content for all language skills, and, equally important, for recycling previously taught vocabulary items into a now familiar type of activity but with different learning outcome, as participants not only had to break the emoji code and retrieve idioms, but also use them in further combinations to find the clues.

Problem Statement

Given the fact that online ESP learning and teaching during the last year has relied heavily on using multimodality and a variety of apps in order to teach and assess all categories of language skills, the actual digital pedagogic value of using these gamified apps remains unexploited. Even if many instructors blended online learning with traditional face-to-face learning scenarios, the gamified apps covered only partially some language skills. Moreover, exploring educational rooms in the field of ESP learning and teaching is still at an experimental stage, as the need to entirely shift to online learning found language instructors with various questions, challenges and difficulties. Likewise, with communication being split between synchronous and asynchronous tasks, discourse within and outside the ESP class entered the realm of a significant Netspeak influence, with emojis and memes being valid reactions to all sort of learner-teacher, learner-learner interaction.

Research Questions

The questions we tried to answer throughout our paper refer to: How effective is the integration of Netspeak features (emoji codes) in the teaching/ learning of vocabulary? Is individual task-based work or collaborative work preferred when learning and practising vocabulary items? What other types of language skills enable learners to improve their productive skills, storytelling in particular? What is the perception of pre-service teachers regarding the impact of storytelling in terms of language acquisition?

Purpose of the Study

The purpose of this paper is to explore the potential of integrating the teaching and learning of idioms in the PIPP ESP class through the communicative approach, both focusing on the task-based instruction and Netspeak influence (emoji code paired with idioms learning) and the collaborative approach (within gamified digital escape rooms). Furthermore, understanding the need to adapt content and learning materials to the digital framework, we discuss good practice examples in which vocabulary items were recycled through written and spoken storytelling tasks, as a means of exposing learners with language chunks while also stimulating their critical thinking and creativity.

Research Methods

The research method consisted in observation of students throughout the formative assessment of vocabulary skills and design and administration of a questionnaire to the undergraduate students enrolled in Preschool and Primary School Pedagogy (PIPP) at Babeș-Bolyai University, Năsăud Extension, 41 of them (out of 55) having entirely completed the form. The respondents have participated in the ESP classes and have completed various tasks related to idioms learning, in three separate modules.

Observation of language acquisition throughout classes and assessment

Firstly, they have been taught the meaning of idioms, through standard instruction, with grammatical and vocabulary gap-filling tasks, with matching or multiple choice practice activities. At the end of this first module, students were assessed based on an online quiz, consisting of various questions from gap-filling, to multiple choice, matching and sentence building. The average grade of 45 students was 3.4, out of a maximum of 5.

Secondly, to test the efficiency of introducing Netspeak elements, the teaching of the new set of idioms involved pairing Netspeak elements ( memes/posters, in this case, illustrating the meaning of the idiom) with the usual instruction. Moreover, to practice and assess these vocabulary items, learners were presented with individual (during synchronous classes) and collaborative tasks ( during the Digital Escape Rooms) in which idioms were coded as emojis combinations and the learnign outcome was to solve the puzzle-like structures in order to get the right idiom. Similar to the first module, assessment also came in the form of a quiz, which had the extra questions regarding emoji coded idioms. The average grade of 47 students was this time 4.6, out of the same maximum score of 5.

Questionnaire research method

The questionnaire consisted of 10 items, with multiple choice, checkbox options and open answer and it was administred through Google forms at the end of the second semester, after learners completed the Digital Escape Room challenge.

Findings

To explore the potential of integrating teaching and learning of idioms through the communicative approach and using the framework of Netspeak features, the tables and figures discussed below will indicate students’ perception regarding the use of these tasks, the manner in which collaborative work enabled them to better learn, the choice of language skills necessary for storytelling or the impact of storytelling in terms of language acquisitions.

Effectiveness and learners’ perception regarding the use of Netspeak features in idioms teaching and learning

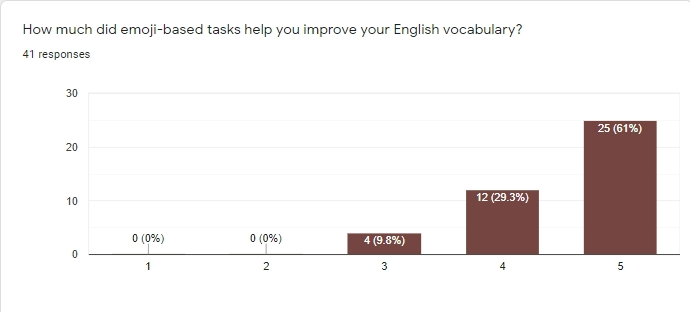

The effectiveness of integrating emoji code as a Netspeak feature in the process of teaching and learning vocabulary items such as idioms was verified through the two quizzes that students took. The first one, administered after a first module of teaching idioms through standard vocabulary and grammar gap-filling tasks, indicated an average grade 3.4, out of a maximum of 5, with 45 students having taken the quiz. After the second module of teaching idioms, in which the practice tasks included pairing explanations with memes of the respective idioms, and emoji coded idioms that learners had to identify, there was a significant increase in the average grade, which was 4.6, out of the same maximum score of 5, with 47 students having taken the test. To verify the students’ perception of the usefulness of such teaching strategies, we addressed particular questions within the questionnaire. As seen in Figure 1 below,

The majority of students (61%) regarded this type of tasks very useful in their personal means of learning idioms, a perception that can be verified and correlated to the above-mentioned average grades in the quiz administered after using this teaching strategy.

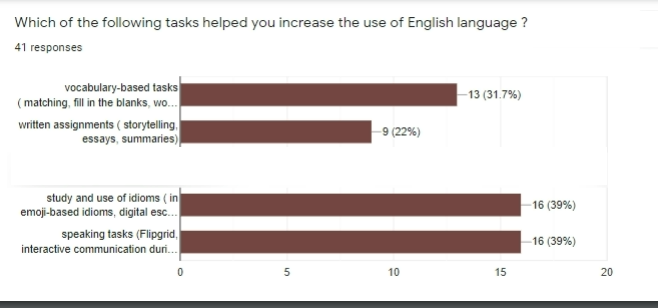

To identify the other throughout the semester while the teaching process was organized based on the communicative approach, respondents were asked to refer to the tasks that enabled them to increase their language acquisition. Figure 2 below indicates that

The tasks that were considered to be most effective were the speaking tasks (based on interactive communication during classes, Flipgrid video recording of storytelling during the Digital Escape Room), 39 % of the respondents having selected this option and, equally important, the study and use of idioms in emoji coded tasks was selected by 39% of respondents. The two types of tasks were ranked highest by learners, whereas the standard vocabulary-based tasks consisting of matching, fill-in the blanks, word formation were chosen by 31.7% of respondents. Written assignments/ tasks in the form of summaries, essays, reports and stories, on the other hand, were selected by the least percentage of respondents (22%), which can be accounted for as a common reluctance among learners to be assessed for their written productive skills.

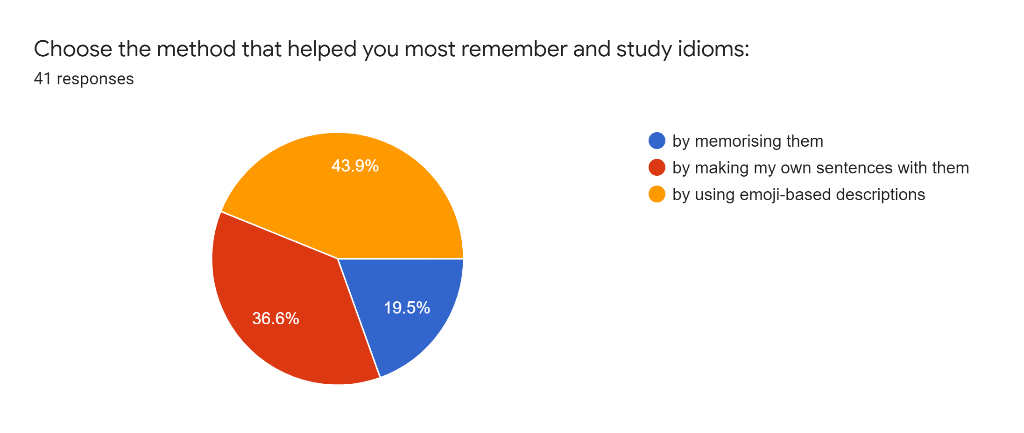

The manner in which students found learning idioms most effective was also part of our interest in the study and one of the questionnaire items asked respondents to identify the best method that helped them learn idioms, by choosing among three options. The results are indicated in the graph in Figure 3 below.

The majority of learners (43.9%) opted for the use of emoji-based descriptions, respectively the method in which, during the instructional phase, we paired standard teaching of idioms with Netspeak elements ( memes, then emoji coded guessing games to practice idioms). Another relevant method referred to creating sentences with the idioms- a task that was designed as a post-teaching phase- and learners were asked to produce oral sentences using idioms that were allocated to them by their peers in a sort of tag your colleague game. 36.6 % of the respondents chose this method, which was meant to stimulate their creativity and vocabulary skills in a communicative learning sequence. Memorisation, still a common means of acquiring vocabulary, was chosen by only 19.5% of the students, which indicates that learners are more responsive to interactive and communicative tasks than the traditional old-fashioned manner of memorising words.

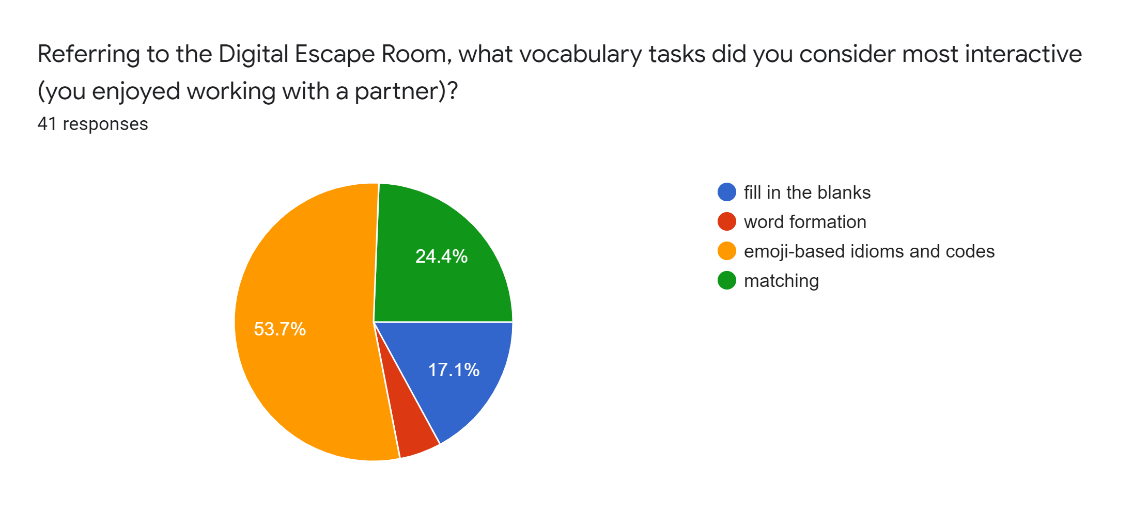

Communication and collaboration- learning vocabulary through the communicative approach

The strategy to organize teaching of vocabulary through the communicative approach required the design of task-based and collaborative learning scenarios that enhanced student-centredness and interactivity. The decision was to integrate these two approaches in a gamified framework, by engaging learners in the Digital Escape Room learning experience, while, at the same time, creating contexts for interactive collaboration. The particular learning sequence embedded in the escape room was to break out of the virtual rooms by cracking emoji coded idioms and by putting together emoji rebuses, among other practical language tasks. Figure 4 below indicates whether learners perceived the digital escape room activity regarding emoji coded idioms interactive, and the majority of respondents confirmed that the task that enabled them to interact mostly was indeed the above-mentioned activity, in which they were asked to identify idioms based on emoji codes.

The majority of learners (53.7%) chose the emoji-based task as the most interactive one, followed by matching activities (24.4%), fill-in-the-blanks tasks (17.1%) and word formation (4.9%). Since the precise identification of emojis is often difficult, the task was even more challenging since emojis were combined so as to render a visual meaning of the idioms. Moreover, this task put to test learners’ ability to use language as a means of communication and to their knowledge of idioms from previously taught classes. They had to use these skills throughout the escape challenge and each team member came up with potential answers that they then had to support their answers.

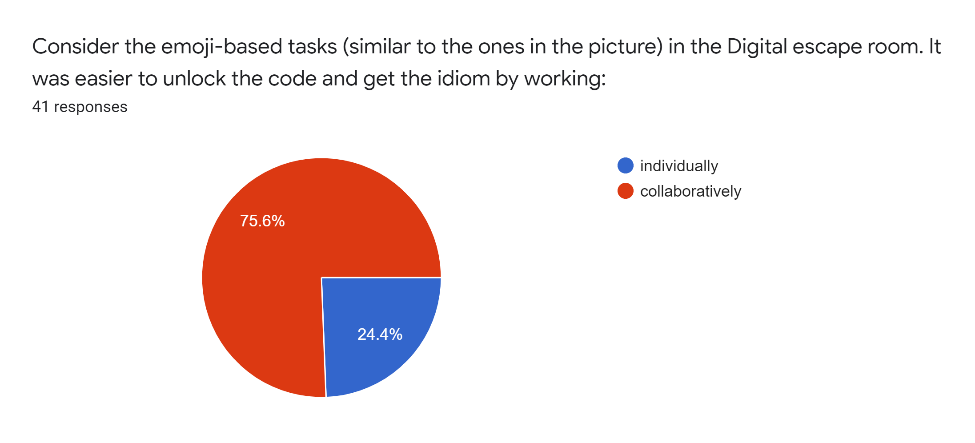

Likewise, the study aimed at indicating the potential of using collaborative tasks while teaching and assessing vocabulary, which was analysed in Figure 5 below, the associated question referring to the whether collaborative or individual work was more effective in deciphering the idioms. The majority (75.6%) answered that it was a collaborative team work and, indeed, students who chose to work in pairs completed the challenge much faster than those who opted for individual work.

Storytelling through the lens of repurposed vocabulary tasks and the communicative impact in students’ language acquisition

The way in which storytelling was used as a learning instrument along with vocabulary acquisition included two sections: the first, designed as a productive skill formative assessment sequence, referred to writing a story starting from a combination of emojis. Having previously taught sequences of a story, linking words and specific vocabulary and idioms to make the narrative more authentic, the task encouraged learners to use creativity and idioms in writing their stories. In doing so, students experienced contextual use of their language skills and their narratives were both well-structured and creative. The questionnaire addressed the following question, in order to grasp which language items were most useful to learners while producing the narratives:The other question,. verified the impact storytelling had as part of the language teaching scenario. Both questions required long answer texts and, according to their own answers, learners identified some of the following elements:

“idioms, stages of storytelling, linking words”;

“writing the story I used lots of elements from class such as: lots of idioms and vocabulary which helped me write the story in a beautiful way and the stages of storytelling enabled me to create a chronological order of events according to the emojis we had to use”;

“storytelling tasks helped me a lot because I had to think about how to solve them. When trying to write a story I had to some research, to read or listen to some stories in English and to figure out how to make the story captivating. I loved the emojis, as they helped me think of suitable adjectives to convey better feelings”;

“ the storytelling tasks were a challenge, but a beneficial one. I stepped out of my comfort zone. Given the fact that we could write the tasks, I had the chance to practise vocabulary, writing and speaking in the Digital Escape Room. I really think these storytelling tasks are essential in increasing the level of language skills.”;

“storytelling activities helped me gain cursive expressiveness and also I felt proud that I used idioms. I only used idioms in vocabulary exercises beforehand.”;

“I really like having to write my own story because I could imagine anything I wanted based on emojis. I always use emojis when I text my friends, but I never thought how meaningful they can be in a writing assignment. I felt really empowered”.

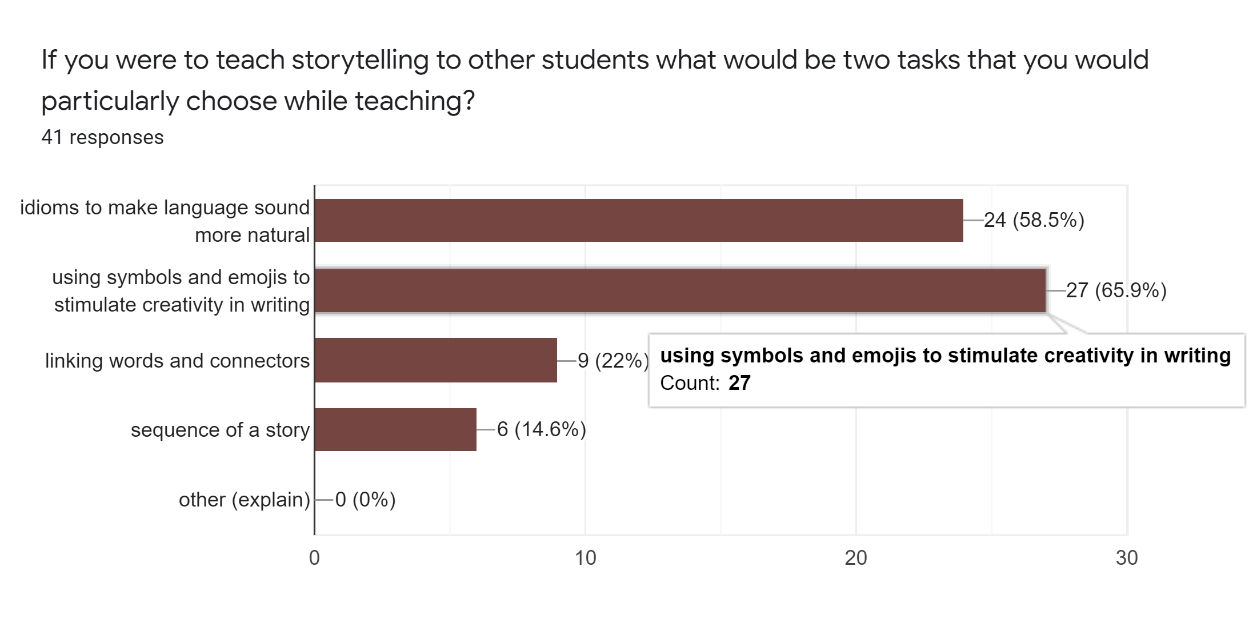

Eventually, one last question that refers to the impact of storytelling and its function to repurpose and recycle vocabulary items was designed with the idea in mind that, as pre-service teachers and future preschool and primary school teachers, storytelling would be a central tool in their teaching strategies. Figure 6 below indicates the respondents’ choice over what other tasks could be associated with storytelling, in a future scenario in which respondents were teachers. Students were asked to choose two tasks out of the list.

The answers that were chosen by the majority of respondents (27 respondents) as the most compatible tasks that go with storytelling was “using symbols and emojis to stimulate creativity in writing and respectively “using idioms to male language sound more natural”, selected by 24 respondents. The answers validate the initial premise that embedding Netspeak features in digital teaching of vocabulary and productive skills would prove successful. Moreover, the same conclusion is doubled by the feedback provided by students upon completing the Digital Escape Room challenge, who were extremely excited by having deciphered the emoji codes.

Conclusion

The experience of teaching ESP in an entirely digital format brought forth a variety of challenges and significantly more opportunities. Experimenting with different platforms and apps customised for language teaching, both teachers and instructors benefited from collaborative work, variety over task choice and multimodality in both teaching and assessment. With the communicative approach at the core of the ESP teaching process, and using the framework of gamification along with the use of Netspeak features in the vocabulary teaching, learning became a more entertaining experience for students. One significant challenge in the digital teaching/ learning process is to customise the suitable apps and gamified resources according to learners needs and interests as digital natives, while, at the same time, keeping the learning principle as the primary scope of education.

To adapt teaching to the Netspeak features that are more and more present in informal online interactions, we customised the teaching of vocabulary items, idioms in particular, by infusing the instructional stage with memes, emojis and other Internet language features. Later repurposed in writing and speaking communicative tasks, and eventually in the form of gamified assessment via Digital Escape Rooms, the study of these language elements was perceived as highly interactive and challenging, enabling learners to use critical thinking, creativity and work collaboratively. The study indicated that learners are motivated and supported throughout their learning trajectory to use their own digital native skills in the language acquisition process. Equally important, by integrating digital language features in ESP language teaching, there is great potential in reusing and repurposing resources by enabling practice of vocabulary skills along with productive skills (writing and speaking). Not only, does this facilitate learning sustainability, but it also paves the way for considering the adaptation of on-site teaching with materials and resources that are better tailored for digital natives.

Eventually, the framework of gamified assessment via Digital Escape Rooms catered for a collaborative learning scenario, which students greatly appreciated and which also worked as a revision stage in the instructional process. Including tasks for all language skills, Digital Escape Rooms were used as an instrument of collaborative learning, in which the challenges stemmed from processing reading tasks, interactive grammar and vocabulary worksheets, speaking assignments, to solving emoji-based rebuses and unlocking virtual rooms by deciphering emoji-coded idioms. More than enjoying an entertaining and complex learning scenario, students were granted high learner autonomy and boosted motivation, many of them having mentioned at the end of the semester that they were positively surprised that they had managed to complete the digital challenge.

Using these resources within the plethora of apps and online teaching materials had a positive strong impact in the learning and teaching experience of this academic year and it confirmed once again that, to make language learning more engaging, one must build bridges between knowledge and skills (language, communication, and soft skills). But these bridges become more durable if we can customise the learning game and spice it up with innovative approaches, resources or learning scenarios, reaching out to learners to participate as active players in the conundrum of ESP language acquisition.

References

Crystal, D. (2004). The Language Revolution. Malden, MA: Polity Press

Crystal, D. (2006). Language and the Internet. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press

Ellis, R. (2009). Task-based Language Teaching: Sorting out the Misunderstandings. International Journal of Applied Linguistics, 19, 221-246. DOI:

Fotaris, P., & Mastoras, T. (2019). Escape Rooms for Learning: a Systematic Review. In Elbaek, Gunver Majgaard, Andrea Valente & Md. Saifuddin Khalid (Eds.), Proceedings of the 13th International Conference on Game-Based Learning (pp. 236-243). Reading, UK: ECGBL Academic Conferences and Publishing International Limited

Gonzalez, J. F. E., Pilgrim, Y., & Viquez, A. S. (2019). Assessing ESP Vocabulary and Grammar through Task-based Language Teaching. Revista de lenguas Modernas, 30, 73-95. https://revistas.ucr.ac.cr/index.php/rlm

Guy, L. (2019). Gamified Assessments-A Literature Review. https://www.testpartnership.com/fact-sheets/2019-gamification-literature-review.pdf

Hymes, D. H. (1972). On Communicative Competence. In J. B. Pride, & J. Holmes (Eds.), Sociolinguistics. Selected Readings (pp. 269-293). Harmondsworth, UK: Penguin

Jacob, R. (2021). The Emoji Code: A Socio-Semiotic Inquiry into the Global Landscape of Reading Language through Image. The Criterion: An International Journal in English, 11(6), 403-426. https://www.the-criterion.com/

Jalolov, J. J., Makhkamova, G. T., & Ashurov, S. S. (2015). English Language Teaching Methodology. Tashkent, UZB: Fanva texnologia

Koivisto, J., Hamari, J., & Sarsa, H. (2014). Does Gamification Work?- A Literature Review of Empirical Studies on Gamification. In Proceedings of the 47th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, (3025-3034). DOI: 10.1109/HICSS.2014.377

Language Policy Unit. (2001). Common European Framework of Reference for Languages: Learning, Teaching, Assessment. Retrieved from https://rm.coe.int/16802fc1bf

Manea, D. (2014). Lifelong learning programs- an effective means of supporting continuing education. Procedia- Social and Behavioral Studies, 142, 454-458.

Manea, D., & Stan, C. (2016). Online communication. In The European Proceedings of Social & Behavioural Sciences. Conference: ERD 2016, VIII. 317-323. DOI:

Mudure-Iacob, I. (2020). Assessment of ESP Language Acquisition through the Lens of Gamification. In C. Teglas, & R. Nistor (Eds), Limbaje Specializate în Contextul Noilor Medii de Învățare: Provocări și Oportunități (pp. 94-108). Cluj-Napoca, Romania: Presa Universitară Clujeană.

Mudure-Iacob, I. (2021). Hide and Seek in Gamified Learning: Formative Assessment of ESP in Digital Escape Rooms. Astra Salvensis. Review of History and Culture, 4(17). 209-217. https://astrasalvensis.eu/

Puren, C. (2020). From an Internationalised Communicative Approach to Contextualised Plurimethodological Approaches [Web log message]. https://www.christianpuren.com/mes-travaux/2020c-en/

Rodrigues, D., Prada, M., Gaspar, R., Garrido, M. V., & Lopes, D. (2018). Lisbon Emoji and Emoticon Database (LEED): Norms for emoji and emoticons in seven evaluative dimensions. Behavior research methods, 50(1), 392-405.

Roschelle, J., & Teasley, S. D. (1995). The construction of shared knowledge in collaborative problem solving. In C. O’Malley (Ed.), Computer Supported collaborative learning (pp. 69-97). Berlin, GE: Springer Berlin Heidelberg

Savignon, S. J. (1972). Communicative competence: An experiment in foreign language teaching. The Center for Curriculum Development. Philadelphia, PA : Center for Curriculum Development. https://books.google.ro/books/about/Communicative_Competence_an_Experiment_i.html?id=51eengEACAAJ&redir_esc=y

Schmitt, N. (2007). Current Perspectives on Vocabulary Teaching and Learning. In S. Cummins, Ch. Davison (Eds.), International Handbook of English Language Teaching (pp. 827-841). Boston, MA: Springer.

Serrat, O. (2008). Storytelling. Washington, DC: Asian Development Bank. https://ecommons.cornell.edu/bitstream/handle/1813/87742/Storytelling.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

Swan, M. (1985). A Critical Look at the Communicative Approach. ELT Journal, 39(2), 76-87. https://www.chubut.edu.ar/descargas/ingles/swan_article.pdf

Ur, P. (2012). A Course in English Language Teaching (2nd ed). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

23 March 2022

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-955-9

Publisher

European Publisher

Volume

2

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-803

Subjects

Education, Early Childhood Education, Digital Education, Development, Covid-19

Cite this article as:

Mudure-Iacob, I. (2022). From Emojis To Storytelling - Enhancing Language Learning Through Collaborative Approaches. In I. Albulescu, & C. Stan (Eds.), Education, Reflection, Development - ERD 2021, vol 2. European Proceedings of Educational Sciences (pp. 642-658). European Publisher. https://doi.org/10.15405/epes.22032.64